Lieutenant Comander Matthijs Ooms

Royal Netherlands Navy

The recent return of geostrategic state competition has brought an end to complacency about interstate war. In the maritime domain, this has increased the prospect of high-intensity maritime warfare. While many Western navies now refocus their training on traditional warfare missions, an important aspect has largely been overlooked: the protection of merchant shipping in the context of a maritime trade war. Although historically, trade protection has been a fundamental task, Western navies and the shipping industry seem dangerously unprepared for it now. To understand and address this, this article will provide a model that explains how trade protection policy is influenced and how a comprehensive trade protection strategy can be formulated.

The COVID-19 crisis revealed the vulnerability of a globalized just-in-time economy. As many countries closed their borders, international air and land transport suffered delays and increased costs. Panic buying of food and other essentials caused empty shelves in supermarkets. While the lockdowns across the world hit the supply and demand side of international trade, that trade, the main artery of the world economy continued to operate. Merchant shipping, carrying ninety percent of the world’s trade, maintained the steady flow of vital energy, food, raw materials and goods, even though many seafarers were dismally confined to their vessels for a much longer time than anticipated. But what if, in a future crisis, an aggressor exploits the vulnerability of a globalized just-in-time economy by targeting merchant shipping? Are Western navies mentally, materially and doctrinally ready for a trade protection task on a grand scale?

The protection of maritime trade has always been a fundamental mission of many navies. Ever since merchantmen began to travel the seas, state and private opponents such as belligerent navies, corsairs and pirates have tried to seize or destroy ships carrying valuable cargo. Indeed, many predecessors of modern navies were founded primarily to protect trade. In 1890, in search of fundamental principles of maritime strategy, Captain Alfred Mahan stated in his seminal work on seapower: “The necessity of a navy, […] springs, therefore, from the existence of a peaceful shipping, and disappears with it […]”.

Classical naval theorists naturally discussed the critical issues of the attack and the defense of maritime trade, but to a varying degree and with differing opinions. John Colomb was one of the first theorists addressing trade protection in an article in 1867. His brother Philip Colomb explored the usefulness of a convoy system under modern conditions in 1887, arguing that commerce protection was the navy’s primary object and reason for existence. The French Jeune Ecole based their asymmetric strategy on severing Britain’s vital – and in their opinion undefendable – lines of communication. Julian Corbett argued that the attack and defense of trade are two sides of the same coin and accordingly addressed both in Some Principles of Maritime Strategy. On the eve of World War I, Kenneth Dewar published a prize-winning essay on trade defense. Referring to Sun Tzu, he urged his readers not only to study their enemy but also themselves, including the workings of the financial system. In the interwar years, Herbert Richmond systematically analyzed trade defense methods and lamented the lack of escort vessels in European navies. In France, Raoul Castex argued that operations to attack or defend trade should be integrated with operations to gain command of the sea. During World War II, Bernard Brodie praised the role of “the lowly freighter” as an essential element of seapower.

Throughout history, countries have suffered from neglecting the defense of shipping. In both world wars, the United Kingdom felt the full importance of trade protection when it was nearly choked by a ferocious German U-boat campaign against merchant shipping. Likewise, Japan suffered heavily during World War II for not adequately addressing the threat to its merchant shipping. Having learned their lesson, Western navies prepared during the greater part of the Cold War for a “Third Battle of the Atlantic” to protect merchant ship convoys with vital food, energy and military reinforcements against a perceived Soviet naval and air threat. However, interest in trade protection against interstate conflict diminished after the Cold War ended.

Atlantic convoy in World War II (Collection: Netherlands Institute of Military History)

In the twenty-first century, maritime trade protection is still a vital priority, although it is not always clearly formulated. Strategic defense documents around the world stress the importance of concepts such as “freedom of the seas”, “flow security” and “maritime security”, which implicitly require a trade protection mission. , Den Haag, 14 Februari 2017, 22; US Navy, US Marine Corps, and US Coast Guard (2007). A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 37; Council of the European Union, European Union Maritime Security Strategy, (Brussels, 2014), 4-8.] Threats to merchant ships still exist in diverse forms. From 2008 onwards, governments from east to west have sent warships to Somali waters to protect merchant ships against pirate attacks. The same area has witnessed incidents involving terrorist attacks on commercial ships and hybrid state-sponsored threats. In June 2019, violent incidents involving tankers near the Strait of Hormuz sent a political and economic shock wave around the world. On a potentially higher level of warfare, Western militaries are becoming more worried by a resurgent Russian navy and a rapidly expanding Chinese navy, which could threaten Western sea lines of communication (SLOCs). However, despite these developments, trade protection has not regained the level of attention it once had.

Maritime trade protection neglected

Many naval strategists have commented on the neglect in doctrine, training and operations of this historically important task. In Seapower: a Guide for the 21st Century, maritime strategist Geoffrey Till agrees that nowadays, the attack and protection of merchant shipping is receiving much less attention than before. Analyzing doctrines around the world, he concludes that trade warfare is rarely mentioned. The US Navy’s latest Naval Doctrine Publication, NDP-1, supports Till’s observation. Although the NDP-1 stresses that ensuring “the safe seaborne movement of friendly commerce and military forces” ranks first among the reasons why naval forces exist, and explains sealift as a primary function, the document makes no further reference to the Merchant Marine, neither is trade warfare recognized as one of the six “primary warfare areas the Naval Service employs to achieve operational objectives”. Likewise, the new US tri-service strategy Advantage at Sea fails to integrate or even mention the other important “service”: the Merchant Marine. On the bright side, last year the US and its allies planned their first opposed cross-Atlantic convoy operation since 1986 as part of exercise DEFENDER Europe 20, although the actual movement was canceled due to COVID-19.

Various other authors have recognized the neglect of trade protection. Ian Speller likewise concludes that interest in the protection of shipping against threats other than piracy has waned. He sees a parallel between the traditional methods of trade protection and the methods employed against piracy. Speller warns that it would be foolish to exclude the possibility of a sustained trade war in the future. Maritime historian Andrew Lambert observes that modern navies are predominantly concerned with terrestrial issues. In his analysis, maritime trade protection has seldom been an issue since 1945, and many states rely on “a combination of international law and shared interest, rather than naval force” to protect merchant shipping. British researcher Martin Murphy warns that, since the end of the Cold War, Western navies have been complacent about protecting maritime trade, while the rise of powers such as China requires a refocus on this task, which is intertwined with economic, financial and maritime warfare.

Milan Vego reaches a similar conclusion from an American perspective and calls for the development of “a theory of defense and protection of maritime trade”, which would form a basis for new doctrine. Furthermore, Vego argues, a cultural change is needed within the US Navy. Currently, naval culture tends to denounce trade protection missions as a lesser form of naval warfare, which explains the lack of focus and preparedness for this task. Vego warns that the US Navy will not be able to fight a high-intensity war at sea if it does not transform its current mindset on trade warfare. Indeed, US military and merchant marine officers have repeatedly called for such cultural change, but apparently to no avail. Most recently, Air National Guard officer David Alman called for a reevaluation of the US Navy’s strategy, as the Navy has neglected convoy defense. On a final note, maritime strategist James Holmes reiterates Mahan’s focus on merchant shipping as an indispensable arm of seapower. Holmes warns that the US has neglected its merchant marine and should learn from its rivals, notably China, to better prepare its commercial shipping for a wartime role.

As the above survey of the maritime strategic literature indicates, the neglect of trade protection against state threats is widely recognized. However, many authors fail to explain the causes of this neglect, other than referring to the end of the Cold War and the subsequent demise of a serious threat to commercial shipping. This article aims to further explore the reasons for the lack of interest in maritime trade protection among Western navies. Do trends in globalization, the shipping industry, and navies justify this complacency and if not, what should be done? To answer these questions, academic literature and trends in the maritime domain will be analyzed.

The article is divided into three parts. In the first part, a definition of maritime trade protection is formulated and related concepts are described. Furthermore, it will investigate whether International Relations theory helps explain its neglect. In the second part, developments in globalization, the shipping industry and Western navies are analyzed to see whether the current complacency is justified. The third part will consider the question of what should be done to improve readiness for maritime trade protection, both at the grand strategic level and within the military domain. Finally, a model will be developed explaining the formulation of trade protection policy and identifying the questions that should be answered in order to develop a comprehensive trade protection strategy.

MARITIME TRADE PROTECTION: DEFINITIONS, CONCEPTS AND THEORY

Definition

Maritime trade protection (also known as commerce protection, protection of shipping, or trade defense) is defined here as the protection of merchant vessels against violence at sea. Conventional threats to vessels include military platforms such as submarines, surface vessels, and aircraft, with lethal armaments including torpedoes, anti-ship missiles, mines, and guns. Unconventional threats include nuclear, biological, and chemical attacks, as well as cyber-attacks, the use of drones, jamming/spoofing (e.g. of GPS signals), and threats from non-state actors such as pirates and terrorists, armed with small boats, handheld weapons, and/or explosives. Maritime trade protection is a significant element of two broader concepts: trade warfare, rooted in military thinking, and flow security, rooted in economic thinking. Both will be further explored.

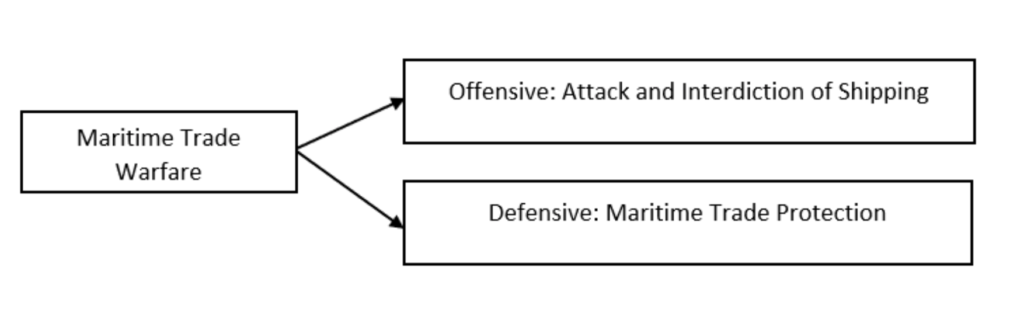

Trade Warfare

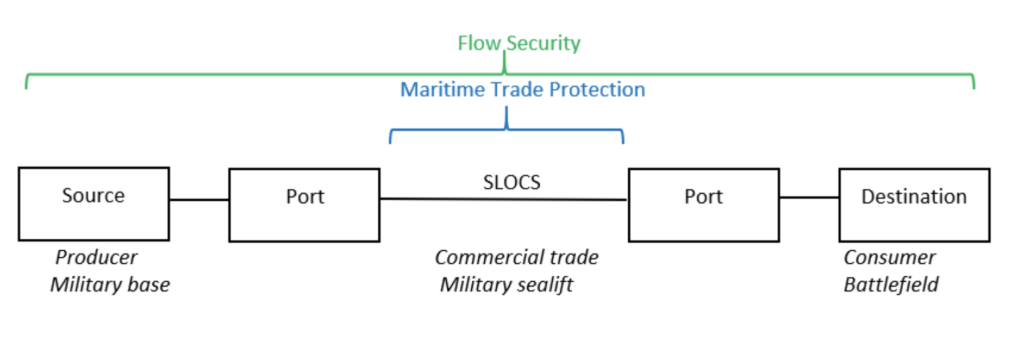

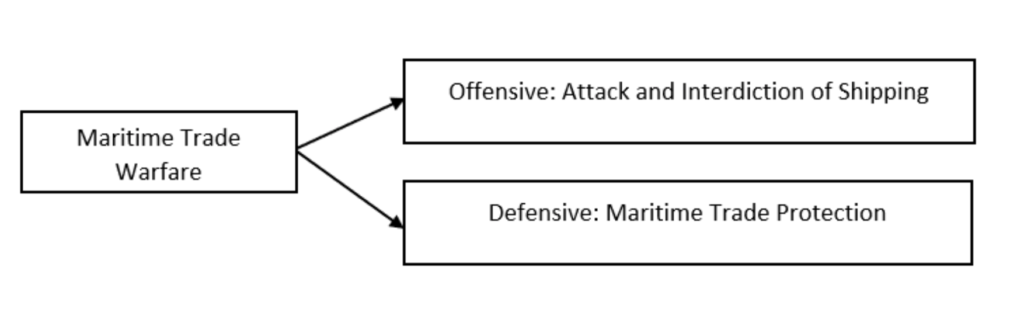

Figure 1. Maritime Trade Warfare

Maritime trade protection is one side of a coin named trade warfare (Figure 1). The other side is its offensive counterpart: the attack or interdiction of shipping, which includes commerce raiding and blockade as its two main methods. The offensive side of economic warfare at sea has many historical examples and draws on a wide body of literature, such as the French school of “guerre de course”, sea denial, and blockade strategies. In the age of sail, ships would be boarded, their cargo inspected and, in case of contraband, confiscated or sunk (the practice of “board and search”). This internationally legalized mode of warfare was brought to highly destructive, morally abhorrent, and legally questionable levels in both world wars with the introduction of the submarine. This was because board and search was no longer practical for small submarine crews, and, more importantly, hazardous when merchantmen were armed. Accordingly, in the later stages of World War I, submarines sank merchant ships without warning. Furthermore, sea mines indiscriminately sank any vessel in their vicinity. Since 1945, the world has not seen an attack on maritime trade on such a scale, although during the Tanker War in the 1980s, 411 merchant vessels were attacked by Iraqi and Iranian forces. As ships have grown in size since 1945, these Tanker War losses equal nearly half the tonnage lost in World War II. On a much less violent scale, Western navies conducted various Maritime Interdiction Operations in the past decades, for example the NATO/WEU Operation Sharp Guard (1993-1996), which enforced an arms embargo upon former Yugoslavia. These operations had more in common with traditional board and search operations from the age of sail than with unrestricted submarine warfare. Such operations show that the attack and interdiction of shipping is a timeless strategy that comes in many forms. It is necessary to understand both the defensive and the offensive aspects of maritime trade warfare.

Interdiction of shipping: air defense frigate HNLMS Jacob van Heemskerck conducting a boarding of a merchant vessel during Operation Sharp Guard in 1993. (Collection: Netherlands Institute of Military History)

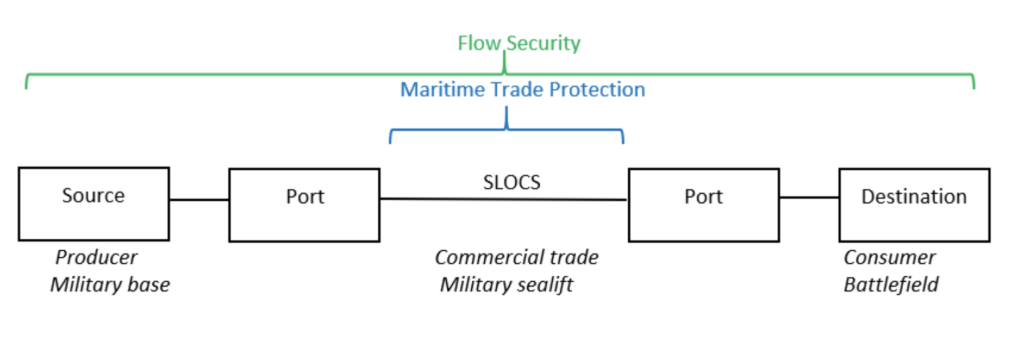

Flow Security

From a wider, systemic perspective, maritime trade protection is part of a concept known as “flow security”. Merchant vessels operating between ports via SLOCs are part of a larger physical flow of commercial or military goods: from producer to consumer or from national military bases to overseas battlefields (Figure 2). Maintaining this flow means maintaining carrying capacity and this is an inherently economic process, which requires more than just the physical protection of merchant vessels. It involves the efficient planning and distribution of cargoes between the limited number of merchant vessels. Furthermore, port and hinterland infrastructure must be able to synchronize with variations in the maritime flow. For example, if a peacetime, continuous, just-in-time flow of goods changes in wartime to an intermittent flow with peaks when a convoy arrives, followed by long periods of inactivity, the port and hinterland infrastructure might become periodically clogged and drained, thereby strangling the flow. In this example, an action that positively affects merchant vessel protection at sea (adopting a convoy system) might actually jeopardize the overall flow. To complicate things further, various government bodies are often responsible for securing separate parts of the flow: in many countries the Department of Defense is responsible for the physical protection of ships in wartime, while the Department of Transport deals with the allocation of cargoes to shipping and with the further land distribution. That said, in many cases other than war, only a part of the flow is at risk at sea, for example when vessels pass areas of piracy or local conflict. In sum, maritime trade protection is part of the larger concept of flow security, and has various stakeholders; only rarely (in wartime) is the complete flow at risk of attack. In this article, the focus will be on the blue water part of physical flow security, thus ignoring aspects such as the security of port infrastructure or digital flow security in undersea cables.

Figure 2. Flow Security and Maritime Trade Protection

International relations theory and trade protection

With trade being such an important driver of prosperity and relations between states, what does international relations (IR) theory say about trade protection and the relationship between naval power and trade? Does trade follow the flag, or does the flag follow trade? In other words, is naval power a prerequisite or a consequence of merchant trade? Can trade replace naval power as an instrument to achieve national ends or does trade enhance peace and profit for all? Scholars have debated such questions for centuries and many arguments have been put forward time and again. Three prominent IR theories, Liberalism, Realism, and Constructivism, provide valuable insights into why trade protection has repeatedly been neglected.

Liberal scholars, such as those in the nineteenth-century Manchester School, argue that shared interest and international law reduce the chances of war. If states refrain from power play and zero-sum thinking, but instead focus on cooperation and peaceful trade, a win-win situation occurs. Commercial Liberalism is based on the idea that free trade promotes peace, as nations will not attack their trading partners and certainly not the trade itself. Liberals argue that in the current globalized world, with extensive economic interdependencies, a high-intensity war against commercial shipping is a lose-lose situation. The economic repercussions would be considerable for belligerents and neutral parties. Furthermore, in their view, the sinking of unarmed civilian ships would be morally abhorrent. For these reasons, Liberals promote not only free trade and globalization, but also international law to regulate or abolish maritime trade warfare, in which they usually receive strong support from the commercial sector. Their historical successes include the ban on privateering and the agreed immunity of neutral trade (1856 Declaration of Paris). Their attempts to prohibit the use of submarines and naval mines were less successful. In so far as Liberals are concerned about military trade protection, they focus more on cooperatively protecting the globalized system and the conditions for trade against irregular threats, at sea and ashore. Maintaining good order at sea, or maritime security, is their primary concern, and not the defense of shipping against other naval powers.

Realism is the dominant theory within military strategic studies. Realists diametrically oppose the Liberal ideas of peace through trade and international law. Instead, their world view is based upon anarchy between states, in which hard power and self-help prevail, while deterrence and the balance of power are the best strategies to guarantee international security. They argue that trade increases the chances of war, as dependency on vital foreign goods such as oil creates the risk of being cut off from those goods in times of tension; therefore states have an incentive to secure these goods by war. Moreover, as political scientist John Mearsheimer argues, states value security over economic prosperity. However, at the same time, many Realists downplay the need for maritime trade protection by military or legal means. Basically, their arguments are twofold: 1) the vulnerability of shipping enhances deterrence; 2) if deterrence fails, the best defense is a good offense. While nuclear weapons command attention as the ultimate means of deterrence, deterring an opponent by threatening commercial shipping is still considered an effective strategy. China’s so-called Malacca dilemma, in which its leaders fear that an adversary will block its oil and gas transports through the Straits of Malacca illustrates the point.

This can work both ways, of course. The notion that nations today are unable to protect their own shipping due to the sheer size of merchant fleets, but can sink other nation’s shipping easily with modern weapons, leads to a peaceful balance of “mutually assured economic destruction”, in the words of an Australian author. This term may sound mad, but in fact, the idea of deterring an opponent with the capture or destruction of shipping lies at the heart of naval strategic thinking. Both Mahan and Corbett strongly opposed the immunity of peaceful shipping in wartime, because they considered firstly that the ability to target commercial shipping was the best preventive of war and, secondly, that navies would lose their reason for existence if that mode of warfare would be abolished. Mahan warned against such abolishment:

Assure the nations and the commercial community that their financial interests will suffer no more than the additional tax for maintaining active hostilities; that the operations of maritime commerce, foreign and coastwise, will undergo no hindrance, and you will have removed one of the most efficient preventatives of war.

Similarly, Corbett argued that “interference with the flow of private property at sea” represented the “great deterrent, the most powerful check on war”. Like Mahan, he warned:

If commerce and finance stand to lose by war, their influence for a peaceful solution will be great; and so long as the right of private capture at sea exists, they stand to lose in every maritime war immediately and inevitably whatever the ultimate result may be. Abolish the right, and this deterrent disappears;

Corbett further argued that naval warfare would be almost inconceivable without trade warfare.

The maxim “the best defense is a good offense” also appeals to Realist thinkers. Translated to the maritime domain, this philosophy results in a focus on offensive battle fleet action. By decisively attacking your opponents’ naval forces, the argument goes, you win command of the sea, which indirectly leads to the protection of your own trade and the obstruction of your opponent’s trade. This mindset, however, has led to a focus on expensive capital ships, rather than larger numbers of escort vessels, and a view that trade protection operations, such as convoying, are too defensive, tedious, and indecisive; as a result, the more direct approach to trade protection has suffered.

Admittedly, most Realists also maintain that there is a positive relationship between naval power and commercial maritime power: national merchant fleets represent national interests that require naval power for protection, be it by offensive or defensive means. Nowadays, however, assessing the national interest involved in the average merchant vessel is difficult since many fly a flag of convenience, have a multinational crew, are operated and owned by companies situated in different countries, and make port calls in multiple continents. Thus, modern merchant vessels are not only the drivers, but also the products and symbols of globalization, rather than symbols of national power and prestige. While national merchant fleets still exist, the globalization of merchant shipping has been undermining the Realist arguments, as British scholar Michael Pugh observed twenty-five years ago.

Constructivism, a third and relatively new school of IR theory, opposes Realist and Liberal assumptions about both anarchy in the first case and the international system in the second. Instead, constructivism focuses on the construction of those ideas, norms, and values which influence behavior between actors. How a nation views itself and remembers its history has more impact on its relations with other nations than Realists or Liberals, with their universal so-called rational-actor models, dare to admit. Although this theory is more conceptual, the maritime domain offers an enlightening example of a cultural construct that many can relate to. It is the dichotomy between seapower states and land power states. The idea that a seapower state or “thalassocracy” is different from a land power in forms of government, foreign policy, and culture finds its roots in ancient Greece, where sea power Athens opposed land power Sparta. Succeeding seapower states in history include Carthage, Venice, the Dutch Republic, and England. According to Andrew Lambert, “seapower” is a constructed national identity, in which the sea is central to its culture, economic life, and security. Among other characteristics, a sea power depends on maritime commerce and uses naval power predominantly to protect maritime trade. Accordingly, states that lose their sea power identity tend to neglect maritime trade protection.

This maritime identity is not a given; it has to be nurtured. Whatever the factual connection to the sea in terms of the volume of maritime trade or the length of the coastline, a “sea power identity” is predominantly the consequence of a mental connection with the sea. Many maritime strategists, although not constructivists per se, have recognized this. Mahan identified the national character and the character of the government as essential elements of sea power, with the tendency to trade being the most beneficial characteristic for the development of seapower. Similarly, Admiral Herbert Richmond argued that the dependence on seaborne trade discerned a “natural Sea Power” from an artificially created seapower. A natural sea power develops bottom-up, as an “expression of a national spirit, of the genius, character, and activity of the people themselves”. From a continental perspective, German Vice Admiral Wolfgang Wegener qualified a nation’s “strategic will” towards the sea as crucial for seapower. James Holmes concurs that culture matters and “policy can reinforce culture and be reinforced by it.” According to Holmes, seapower is a virtuous cycle between commerce, diplomacy and naval power that needs to be maintained by a conscious political choice supported by society. Currently, some scholars argue that China is consciously changing its identity into a seapower state. Western states, on the other hand, seem to be losing their maritime identity. An indication of this is “sea blindness” – the inability of politicians and citizens to understand the maritime domain and recognize the dependency on the sea for welfare and security.

In sum, the leading IR theories produce contrasting explanations as to why maritime trade protection, especially direct naval protection against a state threat, is often neglected. These theories are not just disinterested descriptions of the real world, but can actively buttress political ideologies. In the minds of decision-makers, they shape policy and justify, for instance, the reliance on international law to protect mercantile interests at sea on the one hand or “offensive” capital ships to do so indirectly on the other. To what extent though, can such different arguments be spotted in current debates about trade protection and, more importantly, do world developments justify them and the subsequent neglect of trade protection?

TRENDS IN GLOBALIZATION, MERCHANT SHIPPING AND NAVAL FORCES

Around 90% of the world’s trade is carried by sea in the form of raw materials, manufactured goods, food and energy. Since 1945, the world’s oceans have been more or less secure for the flow of trade. In these peaceful circumstances, the volume of maritime trade has skyrocketed in tandem with new technology, globalization and the promotion of free trade. Suffering sea blindness, most Western citizens are unaware of their dependency on this maritime flow. The freedom of the seas is taken for granted and sometimes the need for navies is questioned. However, this globalized system of maritime trade is more fragile than often assumed, since it faces a variety of economic and military risks.

The modern shipping industry and international policies of free trade have made countries worldwide more interdependent. Many products, food, and energy travel in a just-in-time schedule from port to port. Quayside warehouses filled with goods are a thing of the past and many national strategic energy reserves are kept to a two-or-three-month minimum. Strategic food stocks are practically non-existent; the head of UK’s Countryside Agency warned in 2007 that civilization is only nine meals – three days – “away from anarchy”. Stockpiles seemed unnecessary either commercially or from a governmental perspective since they cost money and the world supply system had never seemed in real danger. Until COVID-19 struck the world.

Globalization after COVID-19: from just-in-time to just-in-case

The COVID-19 pandemic has painfully revealed the vulnerabilities of a globalized just-in-time economy. It disrupted global supply chains, reduced world trade volumes and ignited a debate on the question of whether economic globalization itself will now be slowed, halted, or even reversed. Now, it was argued, dependency on foreign suppliers should be reduced and strategic stockpiles maintained, in case of future shocks. The Financial Times argued that global business should replace its “just in time” strategy for a “just in case” business model. While a comprehensive outline of this ongoing debate is beyond the scope of this article, some views are worth mentioning. Many economists and shipping companies are quite optimistic and do not believe in the end of globalization. Instead, they expect globalization to transform and companies to diversify their supply chains. Some go on to argue that this will result in the need for smaller container vessels that are not dependent on mega ports. Between the extremes of complete self-sufficiency or increased economic interdependence, a more nuanced view on globalization acknowledges both the benefits of mutual trade, and the need to ensure that essential goods can be obtained nationally or regionally. Whatever the future of globalization will look like, it is safe to assume that maritime trade will continue to play a vital role in the world economy and that this trade needs protection, not only against the effects of a virus, but especially against the more likely threat of human violence.

Critics may argue that attacks on trade in the past did not cause serious economic disruptions and certainly not on the scale as the COVID-19 pandemic. In the 1980s Tanker War, less than 2% of shipping was actually attacked and the oil price rose barely 1%. Similarly, during the 2010 peak of Somali pirate attacks on shipping, less than 1% of all ships transiting the Gulf of Aden were attacked. The attacks on two tankers in June 2019 near the Strait of Hormuz caused a spike in the oil price of 2%, while the drone attack on Saudi Aramco oil installations in September 2019 caused a spike of 10%, but even this which was not a serious threat to the world economy. Moreover, the 2020 oil price collapse dwarfed these figures.

While these facts might cause complacency about the risks of trade warfare, there are two reasons for caution. First of all, small percentages can mask significant sums of hard currency due to the high volume of trade and secondary costs. The estimated cost of Somali piracy was 7-12 billion dollars in 2010, while a 1% increase in the oil price represents a yearly loss of 24 billion dollars (2019 average price level). From this perspective, at any rate, a low-cost attack with small boats or drones and explosives is quite effective as an asymmetrical method of warfare.

Anti-piracy operations: HNLMS Evertsen escorting a World Food Programme vessel near Somalia in 2008. (Collection: Netherlands Institute of Military History)

A second reason for caution is that these recent historical cases do not represent full-scale trade warfare between powerful states with modern means and methods. Drawing the wrong lessons from history and underestimating modern trade warfare capabilities has happened before, with tragic consequences. Before World War I, some strategic thinkers, including Corbett, maintained that the risks of trade war were negligible. They argued that historical cases did not give rise to concern and because British trade was so vast, an opponent could at most inflict only a few percent losses in trade volume. Fred Jane, the founder of the famous Jane’s Fighting Ships, strongly disagreed and urged Britain to be prepared against a commerce war, because “it is probably extremely dangerous to under-estimate its danger […] Always it must be remembered that […] the real guerre de course has never been attempted.” Unfortunately, he was right but his warnings were in vain. Historian Bryan Ranft harshly criticized Corbett’s mistake:

By playing down the threat of commerce war he encouraged the already dangerous tendency in the navy not to give its problems adequate consideration. By not following Mahan’s example in emphasizing the permanent tactical advantages of the convoy system he made himself party to the most costly miscalculation in British naval thinking ever made.

Corbett not only downplayed the usefulness of the convoy system, economist and historian Nicholas Lambert argues that he also failed to comprehend the modern globalized economic system of the early twentieth century and its vulnerability to shocks such as an attack on shipping. Corbett had based his maritime theory on the age of sail and downplayed the impact of modern developments such as the steamship, the railroad, the cable telegraph network, and the international credit market. This made Corbett’s assumptions on economic warfare utterly obsolete.

So, in order to fully understand the implications of a full-scale trade war in the globalized twenty-first century, it is better to look at both world wars rather than recent low-intensity conflicts. Some historians argue that even in the world wars, trade warfare was not decisive by itself in the outcome. But even if that were true and a nation decided to renounce offensive trade warfare on that basis, it would still have to be prepared for defensive trade warfare, since an opponent might draw other conclusions on the effectiveness of a war against commerce.

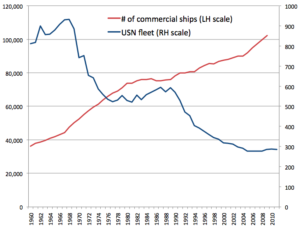

Naval and merchant shipping developments

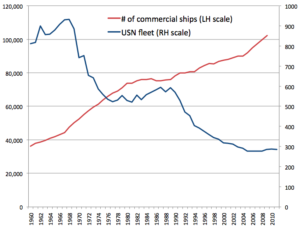

To provide security at sea, naval vessels are a primary asset. The trend for the past decades in numbers of warships compared to the size of merchant fleets both in tonnage and numbers is worrisome. The world’s fleet of ocean-going cargo-carrying vessels has grown from over 17,000 vessels in 1960 to over 46,000 vessels in 2019. In particular, container shipping (introduced in the late 1960s) has grown exponentially in gross tonnage, from 10 million tonnes in 1980 to 266 million tonnes in 2019. In contrast, Western navies have shrunk dramatically in numbers of vessels. The US Navy for example, still the world’s most powerful navy, has shrunk from 909 vessels in the 1966, to 590 in 1990, down to 275 in 2016, although new plans should increase the fleet back to 355 vessels in 2034 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. US Navy fleet size compared to the world’s commercial fleet (1960-2010)

In 2005, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Mike Mullen acknowledged the challenge for the US to provide security at sea around the globe and called for the formation of a multilateral naval force, the 1000-ship navy. In his vision, like-minded nations would cooperate with the US to secure sea lanes against the threats of piracy, terrorism, illegal trade and human trafficking. However, these threats require a policing role, while the protection of shipping in a trade war against a peer competitor requires much more and was not foreseen in 2005. Besides, it is far easier to mobilize nations against a hostis humani generis, an enemy of all humanity, such as piracy, than against a nation-state threat, as illustrated in 2020 by the reluctance of NATO allies to join the US in patrolling the Strait of Hormuz.

Moreover, other NATO countries have shown even a worse decline in naval escort ships compared to their merchant fleets. On paper, the UK has nineteen destroyers and frigates to protect its 513 ocean going cargo-carrying vessels, while the Netherlands has six frigates for its 646 cargo-carrying vessels and Belgium has two frigates for its 64 merchantmen. Even though the capability per platform has increased with new technology, a warship can only be at one place at a time to provide security and not all warships are operationally available at the same time. On top of that, a narrow focus on national flagged shipping is old thinking. Besides shared interests in shipping of partners in coalitions such as NATO, from a flow security perspective, every ship entering a national port constitutes a vital interest that justifies protection, regardless of its flag. In this case, the Netherlands has a security interest in the 30,000 ships annually entering Rotterdam, while Belgium has its interest in the 15,000 ships entering Antwerp annually. , LINK; LINK; Port of Antwerp, Statistisch Jaarboek 2018 [annual statistical report 2018], LINK] The approaches to these ports and other vital waterways (such as the Strait of Hormuz) can easily be blocked with sea mines. Unfortunately, Western naval mine countermeasure forces have declined even more than naval escort forces. Complicating things further, the average size and economic value of a merchant vessel has increased dramatically. Container vessels of 22,000 TEU and supertankers of 300,000 tonnes are not uncommon. Insurance company Allianz estimates that the loss of such a megaship could cost up to two billion dollars. To sum up, while the strategic stakes at sea have increased, the means to protect them have decreased.

Admittedly, there is no golden rule that stipulates the ideal portion of national income generated by maritime trade that should be reinvested in the Navy, neither is there a preferred ratio of warships relative to commercial ships, let alone a formula that takes into account the different naval capabilities and the various levels of national interest within shipping. However, two arguments underscore the intuitive assessment that current Western warship-merchant ship ratios are inadequate. First of all, the Realist argument holds that throughout history there has been a link between naval power and commercial shipping. The larger a commercial fleet grows, the higher the interests that need to be protected, the more a nation is inclined to expand its navy to protect these interests, as already outlined in Mahan’s quote earlier on the link between a navy and peaceful shipping. That the Chinese navy has expanded in the past decades in tandem with its commercial fleet underlines the point even in today’s globalized world.

A second argument why current Western naval strength is inadequate has to do with the nature of a maritime commerce war, which can be characterized as a conflict with a cumulative strategy, as opposed to a strategy that is sequential. Historically, defending shipping in a maritime trade war is resource-intensive, and defensive assets are usually spread over wide areas for long time periods. The outcome of a trade war is not decided by short decisive fleet battles or sequentially planned maneuvers, but over time after numerous encounters between attackers, defenders and shipping. An opponent could well conduct maritime trade war as a kind of guerrilla war at sea, by covertly laying mines or hiding within the maritime environment and suddenly hitting shipping when an opportunity presents, perhaps by submarines or small craft hiding in local seaborne traffic. In this regard, a navy optimized for trade defense should invest in quantity over quality and defensive over offensive capabilities, producing a large number of affordable escort ships, mine countermeasure vessels, and long-range patrol aircraft.

However, Mahan would disagree with such reasoning; he argued that the best way to (indirectly) defend shipping is to neutralize an opponent’s fleet in a decisive battle. In some cases this might indeed be an effective strategy, but an opponent has to agree to give battle, as Corbett warned:

Nor is it more profitable to declare that the only sound way to protect your commerce is to destroy the enemy’s fleet […] What are you to do if the enemy refuses to permit you to destroy his fleets? You cannot leave your trade exposed […] the more you concentrate your force and efforts to secure the desired decision, the more you will expose your trade to sporadic attack.

Moreover, the paramount question is what a modern decisive battle would look like. Does it have to be a symmetric battle between fleets of capital ships such as aircraft carriers, could it be fought asymmetrically with submarines and anti-ship ballistic missiles, or could the battle fleet consist of “dual role” platforms that are very effective either when concentrated for battle, or dispersed for escort tasks? The answer to this question has strategic consequences for fleet composition and flexibility. At any rate, Western navies, with their current size, composition, and offensive capabilities such as amphibious ships and aircraft carriers, are better suited for short offensive maritime operations in the spirit of maneuver warfare than for protracted and dispersed defensive trade warfare operations. Therefore, Western navies would be wise to invest in more balanced fleets.

Escort ships and capital ships: HNLMS Philips van Almonde refuelling from USS Wisconsin during the Gulf War in 1990-1991. (Collection: Netherlands Institute of Military History)

Military sealift

The globalization of the shipping industry poses another problem for Western governments and their militaries: their nation’s merchant marine can no longer fulfil its traditional role as the “fourth arm of defense”. In both World Wars, the sacrifices made by allied merchant mariners, while maintaining the flow of men, military equipment, food and energy across the oceans, contributed just as much to allied victory as the sacrifices made by naval, army and air force personnel. Merchant shipping plays a vital role in providing military sealift, either sailing armed in convoy under naval control, or sailing unarmed and independently in a more benign maritime environment. Since the end of the Cold War, preparing the merchant fleet for this role has not been a priority for Western governments; not to mention the fact that due to globalization and flagging out, many Western merchant fleets are only a shell of their former selves. Further, 90% of world shipbuilding takes place in Asia and most Western countries no longer have the shipbuilding industry to sustain a war effort. A large proportion of the ships that are still owned by Western companies sail under a “flag of convenience”. Moreover, even nationally flagged ships have crew members of different nationalities. It is questionable if foreigners will serve in harm’s way for a national cause if it conflicts with their own beliefs and loyalties.

On top of the effects of globalization on national sealift, a wartime role for national or allied merchant ships is problematic because the material, training and procedures to execute this role have dwindled. Stocks of gun armament and protective systems such as degaussing for merchant vessels were disposed of during the last decades of the Cold War. Training between naval and commercial shipping, such as sailing in convoy, is seldom practiced. In fact, at the turn of the century, the NATO doctrine of Naval Control of Shipping (NCS) was replaced, without much organizational or academic debate, by a more “loose” doctrine of Naval Coordination and Guidance of Shipping (NCAGS). The traditional direct naval control of shipping is now considered less likely and instead a more voluntarily relationship of information sharing between navies and merchant shipping is advocated. Recently, an American Merchant Marine captain warned that he is not ready to perform a wartime role with his ship, as he has never been trained for such circumstances. Indeed, in the US, many professionals from the Navy as well as the Merchant Marine have raised the alarm bell about the lack of sealift capacity in times of conflict. In contrast, China is maintaining a large merchant fleet of nationally crewed vessels, which are built according to technical standards for wartime use. These ships enhance China’s expeditionary warfare capabilities and they regularly exercise with naval vessels while performing amphibious roles or Replenishment At Sea (RAS).

Critics might say that the above mentioned is outdated Total War thinking. Of course, questions can be asked if convoying, guns and degaussing systems are the right ways and means for twenty-first-century threats. In like manner, just before World War I, Corbett questioned the value of convoys, because he judged all conditions for their effective use had changed dramatically since the age of sail:

Modern developments and changes in shipping and naval material have indeed so profoundly modified the whole conditions of commerce protection, that there is no part of the strategy where historical deduction is more difficult or more liable to error.

The world wars that followed showed that Corbett’s skepticism of the convoy system was utterly unfounded, although they also showed he was right about the inherent difficulty of drawing the right trade defense lessons from history.

No matter how difficult it is to distill an adequate commerce protection strategy from history, a discussion about modern ways and means is fruitless as long as the “ends”, the need for maritime trade protection, have not been properly recognized. Moreover, secure sealift is not only a total war requirement. Expeditionary operations cannot start without sealift and it is questionable if the commercial market will provide it, especially for high-risk Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) environments. During the Falklands campaign in 1982 for example, the British Task Force to recapture the islands sailed with more merchant ships than warships. A maritime historian and former merchant naval officer neatly summarized this contribution in his book title: They couldn’t have done it without us. The merchant ships in the Falklands campaign were almost exclusively British flagged and crewed. Furthermore, the Cold War context of 1982 made these merchant ships, their crewmembers and the Royal Navy technically and doctrinally more prepared for this wartime role than nowadays is the case, which makes a repetition of such an operation today impossible. A similar dependence on sealift was seen in the 1991 Persian Gulf War and the 2003 Iraq war, in which transport vessels contributed to the war effort with respectively 459 and 155 shiploads.

Threats to merchant shipping

Summing up the above analysis: the world’s merchant fleet has grown in size and is highly globalized; there are fewer warships to protect them and merchant ships in the West are unfit for a wartime role. So the stakes at sea are higher, the means to protect them lower. Perhaps that is acceptable when there is no clear and present danger? After the end of the Cold War, for many the “end of history” seemed to have arrived, with the prospect of democracy, free trade and prosperity for all. While local conflicts around the globe soon tempered these expectations, the maritime domain seemed to fulfill the Liberal promise of a peaceful world dominated by trade and international cooperation, as there were no serious threats to shipping, save for pirates and terrorists in specific areas. In the past decade, however, anxiety for conflicts in the maritime domain has increased due to the rise of China, the resurgence of Russia, the continued bellicose stance of Iran and North Korea, and local conflicts as in Yemen that have spilled over to nearby shipping routes.

But would a modern nation-state, in case of conventional war, attack its opponents’ shipping? Due to globalization, there are few truly national fleets to target. Almost every cargo ship represents interests of different nations: those of the flag, the owner, the crewmembers, the charterer, producers and consumers. Therefore, the Liberal argument goes, an attack on modern merchant shipping is an attack against the world community, and probably also against the aggressor’s own interests. However, in war, belligerents calculate risk, costs and benefits and proceed accordingly, sometimes correctly, sometimes not. Neither in the age of sail nor the Iran-Iraq Tanker War did crews of mixed nationalities safeguard merchantmen from foreign attack.

But what about capabilities and intentions today? Currently no country seems to openly prepare for a full scale trade war comparable to both World Wars, although Iran still occasionally harasses shipping, Russia has recently conducted naval exercises to demonstrate a capacity to disrupt NATO cross-Atlantic reinforcements and in USNI Proceedings two American authors advocated that the US should revert to privateering to attack Chinese global trade. Nevertheless, history shows that pre-war opinions and capabilities can change in wartime. For example, before both World Wars the German navy did not openly advocate unrestricted submarine warfare, nor did it have enough submarines to execute it effectively, but all that changed during wartime. Similarly, the US immediately reversed its stance opposing both “belligerent rights” and unrestricted submarine warfare after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Law, technology and trade warfare

Besides the unpredictable developments in international relations, there are two other factors that increase the risk of escalating maritime trade warfare: law and technology. The international laws regarding trade warfare are in essence still the rules of board and search from the age of sail. Inspecting the cargo of a nineteenth century sailing vessel is not comparable to inspecting 20,000 containers on board a modern container vessel. Even the containership’s captain does not know the exact details of each container, so boarding teams are confronted with an impossible task. If international law does not fit the real world, there is a risk that it will be thrown overboard completely, with dire consequences, as researcher Steven Haines warned in an International Red Cross report on modern war at sea.

Secondly, technology creates new risks. Modern vessels are more dependent than ever before on onboard computer systems and electronic navigation systems, which are vulnerable to hacking, spoofing and jamming. This enables a new, low cost form of offensive cyber trade warfare. Finally, in the near future, unmanned vessels will sail the seas. Without human beings on board, the moral threshold in attacking shipping will be lowered, if the aggressor even had such moral qualms in the first place. Sinking a ship could thus be regarded as just destroying property, a purely economic action, although with collateral environmental effects. All in all, due to an increased risk in state competition, developments in technology and outdated international law, the threat to maritime trade is increasing rather than decreasing in the near future. So, how should Western governments and their militaries respond?

WHAT SHOULD BE DONE TO IMPROVE READINESS FOR MARITIME TRADE PROTECTION?

Unfortunately, maritime trade protection is not just a naval problem that can easily be solved by reshuffling naval priorities or allocating more defense budget to the Navy. Although a better balance between naval and commercial vessels would improve the ability to protect trade, as previously argued, there is more that needs to be done. The fundamental problem of maritime trade protection is its multi-domain nature: it crosses academic, political, governmental, commercial and military boundaries, as will be further explained.

Arguably, there is not a single academic discipline, political ideology, government agency, shipping company or naval branch that by itself takes up trade protection as its core focus, nor has the ability to singlehandedly address it. A diffusion of responsibilities inhibits action: trade protection seems to be everyone’s problem but nobody’s job. At the academic level, maritime trade warfare crosses the fields of economics, history, strategy, political theory, international relations, international law, military operational sciences, to name but a few. At the level of international politics, opposing ideas from different IR theories, based on experience processed as history, drive policy decisions; Liberals tend to rely on international law and mutual interest to protect trade, while Realists prefer deterrence and offensive naval power.

At the level of national politics, trade protection requires aspects of both left and right-wing thinking. Right-wing parties usually prefer to spend more on defense than left-wing parties. Left-wing parties, on the other hand, are generally more favorable to state intervention in economic affairs. In times of crisis such intervention is crucial. For example, historian Martin Doughty demonstrates in his analysis of British inter-war planning how the idea of minimum state intervention hampered Britain’s preparedness to manage wartime logistics, including administering the merchant fleet. Similarly, the COVID-19 crisis urged many governments to intervene much more in economic and public affairs. In other words, resilience in trade defence requires not just a strong military, but also a strong civil government, capable of coordinating economic affairs in times of crisis.

Next, maritime trade protection is a dual responsibility for shipowners and governments, as ship owners and merchant crews can take precautionary measures by themselves to either prevent becoming a victim of violence at sea or reducing the impact when it happens. Within most Western governments, various departments are involved in aspects of trade protection, such as the Ministries of Transport, Economics, Foreign Affairs and Defense. Within the Department of Defense, the Army is often more concerned about sealift issues than the Navy, as a lack of sealift impairs the army’s ability to fight land wars on overseas battlefields, while it doesn’t necessarily affect the Navy’s ability to fight sea battles or project power ashore. Moreover, even though many navies claim maritime trade protection as their core responsibility, there is no naval branch that culturally fosters this task. In this aspect, there is a striking analogy between counterinsurgency and maritime trade warfare, as noted by the Australian scholar and Rear-Admiral (ret.) James Goldrick:

The truth is that economic warfare at sea […] is an extraordinarily complicated subject and one which navies generally do not have a good record in considering, preparing for, or initially conducting. There may here be an analogy with counterinsurgency and the emotional and cultural problems which this aspect of warfare presents for armies—such as the tendency for counterinsurgency doctrine and training to be relegated to the bookshelf as soon as circumstances allow a return to more “conventional” areas of warfare. As with armies and counterinsurgency, in time of peace navies often don’t think enough about, don’t plan enough for, and don’t have sufficient mastery of the ins-and-outs of economic warfare at sea. Which are considerable.

Indeed, many in the military resist missions that diverge from their supposed primary goal of fighting and winning conventional wars. This is not only the case for counterinsurgency, but also for peacekeeping operations, as UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld’s famous “paradox” suggests: “Peacekeeping is not a soldier’s job, but only a soldier can do it.” Framed similarly, maritime trade protection is culturally not a job that navies prefer to conduct, but the important distinction is that it should be one of their prime responsibilities.

As a case in point, RAND Corporation analyst Carl Builder concluded in 1989 that the US Navy has a cultural preference for power projection missions and aircraft carriers, because “sea lane protection called for a different and less interesting navy”. He argued that it was not the threat that drove the US Navy’s concept of war and the required naval forces, but it was the other way around: the culturally desired forces (capital ships) drove the concept of war and, hence, the interpretation of the threat. Likewise, World War II veteran Capt. USN (ret.) Roland Bowling concluded in his dissertation that, during the greater part of the twentieth century, the cultural legacy and selective reading of Mahan resulted in a preference for capital ships and decisive battles at the expense of the protection of shipping.

The reluctance to focus on trade protection might also be explained on the basis that it is too complicated to adequately prepare for or execute. However, the analogy with counterinsurgency can be instructive: Western militaries have painstakingly learned to address the challenges of counterinsurgency with a comprehensive approach. Similarly, maritime trade defense requires a whole-of-government approach at the grand strategic level and specific doctrine, training and organizational focus for the military domain. Therefore, a model will be provided to better understand the dynamics of trade protection policy. Based on this model, a comprehensive strategy can be formulated. The military instrument of power is the most prominent instrument for maritime trade protection. Thus, specific steps for military improvement will be provided here.

Trade Protection Policy Model

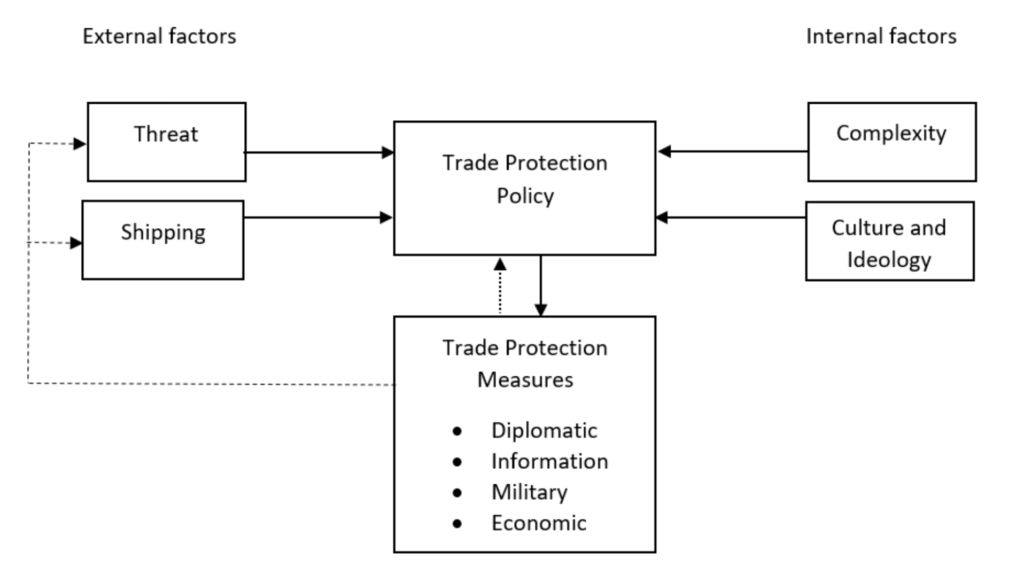

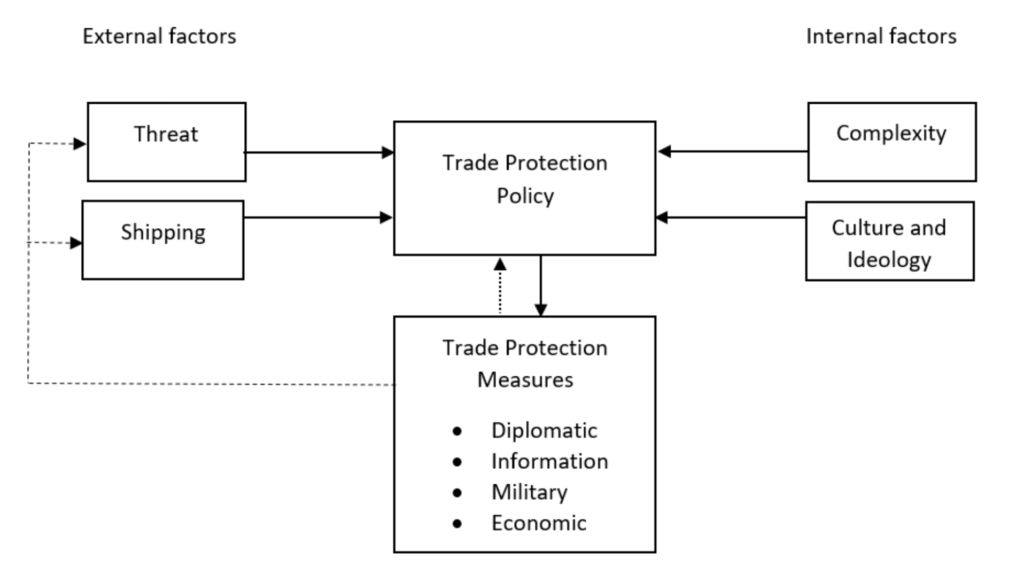

To understand what drives or hinders a government in pursuing trade protection policy, what options are available, and how each component influences each other, a model is provided, which integrates previous arguments and observations (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Trade Protection Policy Model

Trade protection policy is influenced by two external factors, main drivers for policy, and two internal factors, which can inhibit action or push for a certain selection of trade protection measures. Each element will be looked at in turn.

Threat and Shipping

The external factors are: a threat and merchant shipping that requires protection. Without either, there is no need to formulate trade protection policy. However, it is difficult for a country to analyze these two factors objectively. How a government perceives a threat and, secondly, the national interest in shipping are, in practice, what count. This perception is influenced by culture and ideology, as will become clear later. The threat to shipping can range from low level piracy to high intensity interstate commerce warfare. The shipping factor is that part of international shipping that requires protection. A primary factor determining this part is the national interest, which can be defined according to flag, ownership, crew nationality or other factors. Furthermore, trade protection policy can be focused on, or legally limited to, ships operating within a certain area, such as a high risk area, the NATO treaty area or international waters. Finally, trade protection policy can be focused on certain types of shipping, such as military sealift or humanitarian aid transports. The type of threat also dictates what type of shipping is most vulnerable and requires protection.

Complexity

Turning now to the internal factors that direct policy, the complexity of trade protection, as previously explained, can inhibit effective trade protection policy. Historically, a recurring issue of internal debate is caused by a diffusion of responsibilities. Who is responsible for trade protection, and who pays for protection measures, depends on the circumstances, such as the nature of the threat and the type of shipping involved. Complexity is further increased when policy has to be coordinated with allies, especially when a stronger and influential ally has a different view on trade protection measures. Furthermore, cultural differences between civil government, shipping companies and the military add to complexity. Finally, complexity is increased by the variety of trade protection measures. In sum, a complex whole-of-government approach is required, in close cooperation with the commercial sector, to reach agreement on the severity of the threat, the shipping that requires protection and the protective measures to be taken.

Culture and ideology

Culture and ideology are internal factors that influence trade protection policy in three principal ways: they act as a filter towards the threat and shipping factor, they increase the complexity factor and they create a bias towards preferred trade protection measures. Culture and ideology are related concepts and therefore grouped as a single factor. Culture is formed by historical experience, education, institutional or national norms and values. Ideology, which can be influenced by culture, is a theoretical framework, a compelling world view that shapes policy. Ideology, as shown by the previous discussion of Liberal and Realist perspectives, frames political questions about the relationship between trade and war, about state intervention in economic affairs, about international cooperation and self-interest. Constructivism on the other hand regards culture and self-image as prime factors in explaining state behavior. In this light, sea blindness is a cultural phenomenon: the less a society feels connected to the maritime domain, the less it will devote to maritime trade protection. But even consciousness about maritime trade might not always be a blessing. A negative attitude in society against free trade and globalization, as increasingly witnessed in the West these days, could negatively influence the willingness to protect (international) maritime trade. As a further example of the cultural factor, a common cause of misperceiving an enemy is mirror-imaging, which derives from a cultural bias. Another manifestation of the cultural factor is the preferred solution to a threat, in other words, the selection of trade protection measures. A strategic culture influenced by Realism might prefer offensive military action, while a more Liberal culture would be inclined to choose diplomatic action and cooperative defensive measures.

The effects of culture and ideology on trade protection policy can be seen in the international reaction to Somali piracy. While the factors “threat” and “shipping” were similar to Western, Indo-Pacific and other states, the choice of protection measures differed. While China, India, South-Korea, Japan and Russia primarily focused on national convoys with naval escorts in the Gulf of Aden, Western nations under EU or NATO flag chose zone protection throughout the Gulf of Aden, indirectly protecting all shipping regardless of nationality. Furthermore, while the Indo-Pacific states remained on the defensive within the main shipping lanes, Western nations soon took the initiative, searching for pirates in the wider Somali Basin, blocking pirate camps with amphibious assault ships near the Somali coast or even conducting special forces raids against pirate equipment ashore. Furthermore, among all nations, differences emerged in the allowance of private armed guards on merchant ships, due to ideological differences within government and society regarding the monopoly on violence. In short, the formulation of trade protection policy and the choice of trade protection measures is not a straightforward rational process that fits the threat and the shipping that needs protection. It is also influenced by the conscious and unconscious effects of evolving culture and ideology.

Trade protection measures

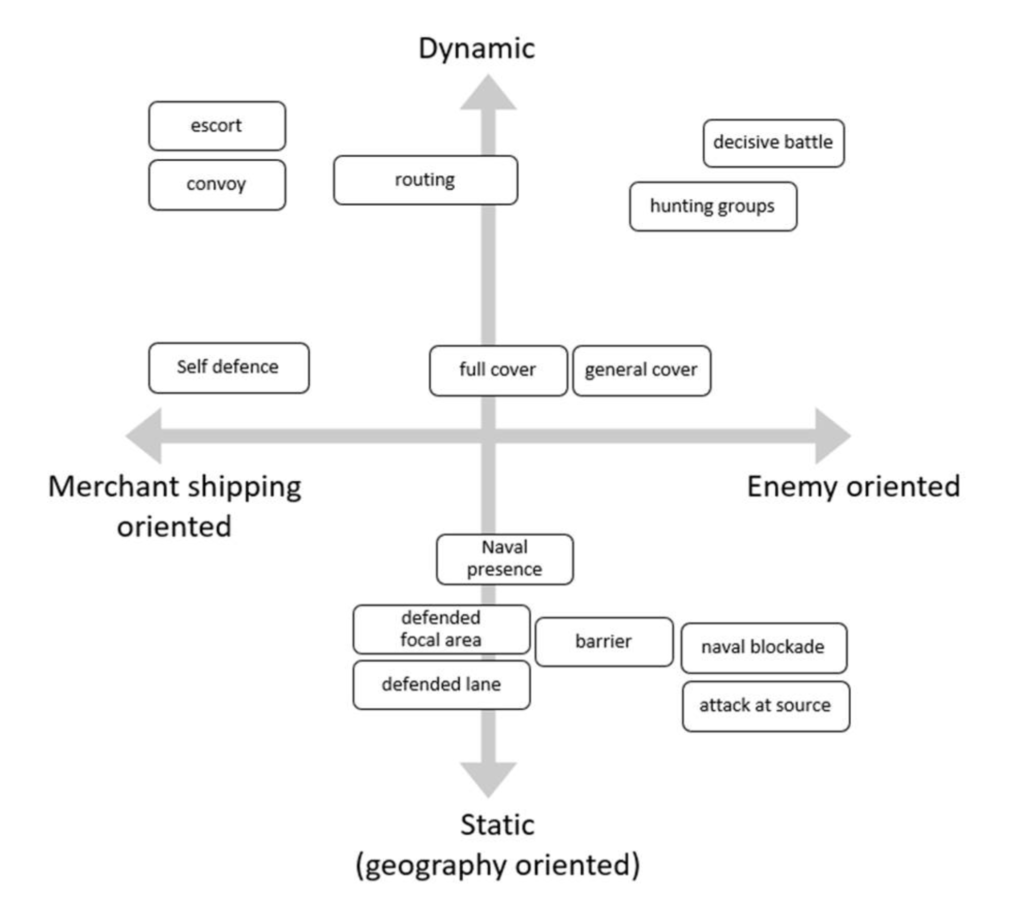

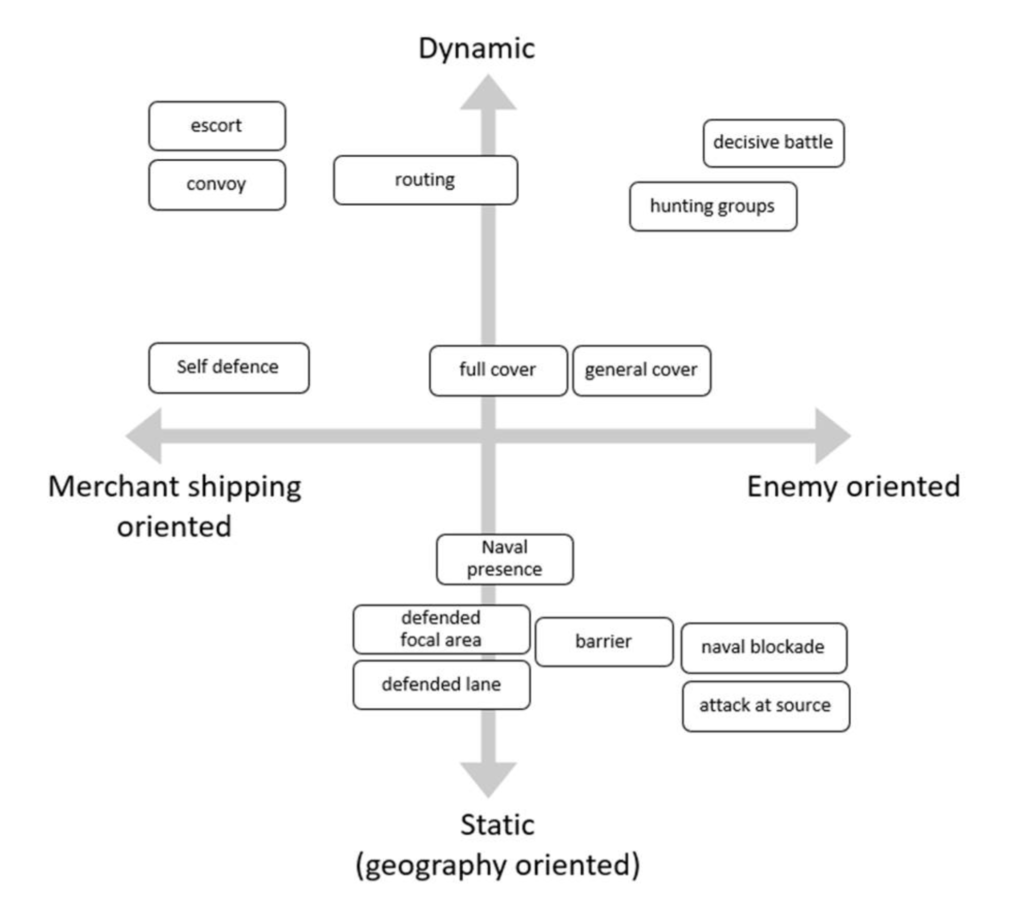

Trade protection measures can be grouped according to the four instruments of national power: the diplomatic, information, military and economic instruments (DIME). The military instrument is the most prominent. Scholarly works on maritime strategy and military doctrines provide an overview of time-tested concepts such as convoying or attacking the source of the threat (Figure 5). To understand the fundamental differences and similarities between these concepts, Figure 6 offers an insightful visualization. The military methods of trade protection can be differentiated in two relative dimensions. First, the distinction between “maritime shipping oriented” and “enemy oriented” methods relates to the differences between indirect/defensive measures and direct/offensive measures. Second, methods can be “static” (geography oriented) or “dynamic”. This relates to the enduring debate as to whether trade defense means either defending actual ships or defending the notional concept of a sea lane, focal area or SLOC. It also relates to the operational differences in detecting and defeating a moving enemy fleet at sea or attacking or isolating an enemy fleet fixed in port.

|

Geoffrey Till

Seapower

|

Ian Speller

Understanding Naval Warfare

|

AJP 3.1

|

- Indirect and general fleet cover

- Indirect general cover at focal points and on patrolled sea lanes

- Attacking bases

- Direct defence: convoy and escort

- Other means of defence

|

- Cover

- Distant and close escort

- Naval Cooperation and Guidance for Shipping

- Convoying

- Hunting groups and patrolled zones

- Attack at source

|

- Sea Control

- Distant and Close Escort

- Naval Cooperation and Guidance for Shipping

- Convoying

|

Figure 5. Military measures to protect trade according to literature and doctrine

Figure 6. Military measures to protect trade differentiated in two relative dimensions: merchant shipping oriented versus enemy oriented and dynamic versus static.

Examples of using the other three instruments of national power for trade defense are as follows. A diplomatic measure might be promoting the reflagging of ships to a neutral flag or to a flag of a state with a strong navy, as well as upholding international law and instituting sanctions against lawbreakers. An example of the information instrument would be the use of intelligence to identify and mitigate threats, or the use of counter-narratives against state or non-state opponents. Information can also be directed towards the domestic population to increase a nation’s sea-mindedness. Finally, economic measures can reduce vulnerability from a flow security perspective. Examples are fiscal stimulation for the national maritime sector, to maintain a pool of ships, crews and shipyards, which can secure national needs in times of conflict. Next to protecting the maritime flow, (temporary) economic alternatives to maritime trade could be considered, such as strategic stocks, rationing, air and land transport, energy diversity and increasing output from domestic resources.

While trade protection measures should normally be the outcome of the policy formulation process, sometimes an instrument of national power can also be a push factor and influence the policy formulation process (hence the dashed upward arrow in the model, see Figure 4). For example, when a sudden threat to shipping arises, the current national toolbox limits the available options, while the Navy might press for the use of its assets as the solution to the problem. Furthermore, the selected measures influence the driving factors “threat” and “shipping”, as an opponent may change tactics in response, or a national shipping company might reflag its ships to a country that provides better protection (hence the dashed arrow between measures and threat/shipping).

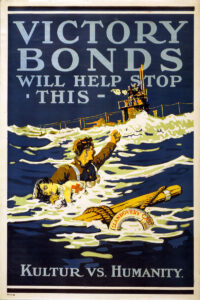

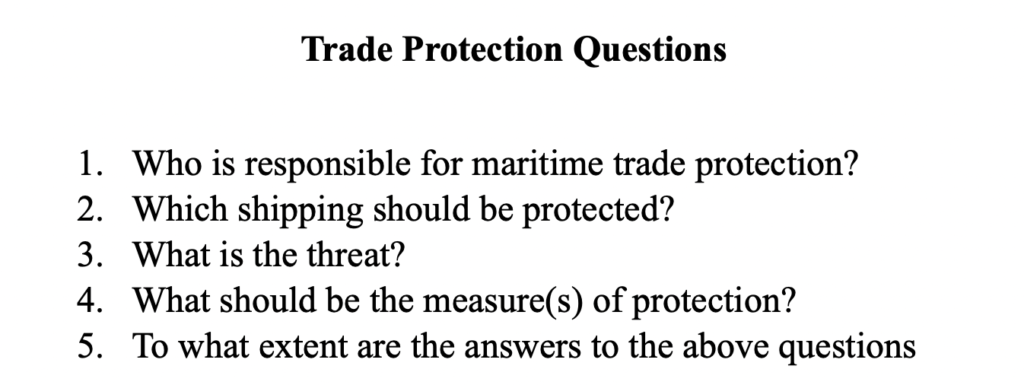

Maritime trade protection questions

To formulate an effective trade protection policy, a comprehensive approach is required. Based on the Trade Protection Model, five questions should therefore be answered (Figure 7). , Militaire Spectator, 189.3 (2020), 126-143. The article argues that the first four questions repeatedly troubled Dutch policymakers when formulating trade protection policy during the Cold War (1949-1989) and during the peak of Somali piracy (2007-2013).]

Figure 7. Trade Protection Questions.

These apparently simple questions are seldom asked, let alone answered. The complexity factor is addressed by the first question which should be: who is responsible? The responsibility for protecting merchant vessels could lie with the government, the shipping companies, or both. This also determines who pays for protective measures. For the government, the response could be a legal obligation or a political choice. Within the government, several bodies can be involved in maritime trade protection or the wider question of flow security. At an international level, cooperation can be required with allies and international organizations. This all adds up to challenging inter- and intra-governmental coordination.

The second question is: who should be protected? This addresses the shipping factor. The answer can be clear or ambiguous, based on factors such as nationality (of ship owner, crew or flag state), type of vessel (e.g., only with military cargo or all civilian shipping) or location (e.g., on the high seas, in port, or within a treaty area or a declared high-risk area).

The third question deals with the threat factor: against who or what is protection needed? The nature of the threat determines which shipping is most vulnerable and which protection measures are most effective. Therefore, the third question links the second and fourth questions. The threat could originate from a state or a non-state actor, which results in different offensive ways and means. While there are obvious differences between the threat of a nuclear attack submarine and a pirate skiff, the possible trade protection measures can be, on a conceptual level, similar (Figures 5 and 6).

The fourth question is the most controversial one: what is the best method of protection? Geoffrey Till qualifies this question as “the most contentious of all issues of maritime strategy, not least because there was, and is, no single solution to the problem, and few simple answers.” While works on maritime strategy and maritime doctrines provide possible military solutions, a wider lens should be used involving all instruments of power, as indicated in the Trade Protection Policy Model. Although this rather complicates than simplifies answering the question, a comprehensive strategy requires such broad analysis.

Finally, the fifth question acts as a self-reflection method to overcome a cultural or ideological bias. If other countries are facing a similar threat, but react with very different protection measures, then this could indicate that such a bias is overshadowing more effective measures.

Are current military ways and means adequate?

Are the traditional ways and means of naval warfare adequate to address the threat to shipping? From a Realist naval perspective, establishing command of the sea by defeating the maritime opponent in battle seems a logical method to eliminate any threat to merchant shipping. Such an offensive strategy might work against a symmetric opponent seeking decisive battle, but it is futile against a conventional enemy choosing a sea denial strategy, or against an unconventional opponent blending in local maritime traffic, or if a neutral stance is required in a local conflict. In these cases, sea control is required in the vicinity of merchant shipping, which could be practically everywhere. This is an impossible task for even the largest navy in the world, given today’s numbers of merchant ships and naval assets. Even so, a critic might argue that against threats such as submarines, small boats, mines and aircraft, current naval ways (doctrine) and means (platforms) are adequate, provided that sufficient numbers are available and the threat is confined to a limited area.

Certainly, platforms such as frigates, minehunters, patrol aircraft and submarines are important means to defend shipping. However, most current tactics and exercises focus on a unit’s self-defense or on the protection of a single, military, high-value unit such as an aircraft carrier or amphibious assault ship. Defending dozens of large merchant ships like tankers and container vessels in a confined convoy or extended sea lane is a completely different situation. And that is only the naval side of the story. Even with adequate naval doctrine and training, most merchant ships lack sufficient manning, training, secure communications and flexible engine configurations to sail in close quarter convoys for an extended period. Moreover, merchant mariners have a different mindset. Where a navy sails in harm’s way for a political goal, merchants sail for economic gain, while avoiding danger when feasible. Peacetime training should be used to understand these cultural differences and establish the mutual trust needed to prevail in times of conflict.

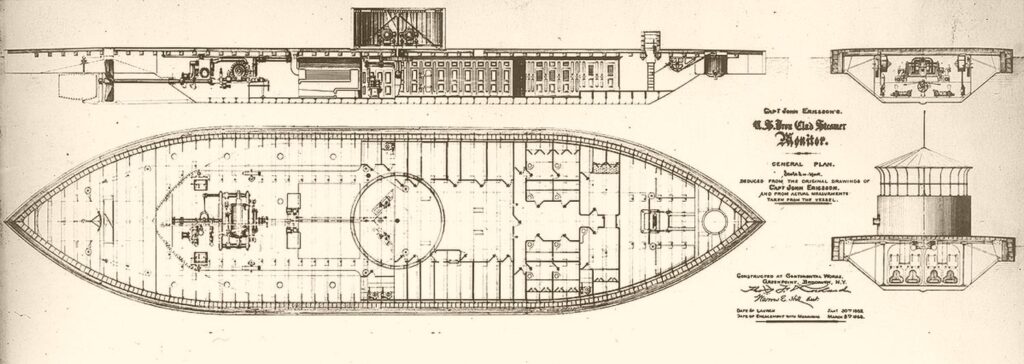

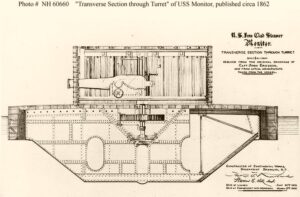

Recognizing trade warfare as a distinct warfare area

Maritime trade warfare should be appreciated as a distinct part of naval warfare, like amphibious warfare. Both forms of warfare cross boundaries and are more than the sum of their parts (including Anti-Air Warfare, Anti-Submarine Warfare, Anti-Surface Warfare and Mine Countermeasures). They require understanding and coordination between different stakeholders, specific doctrine and organizational standing. While amphibious warfare crosses the physical, cultural and doctrinal border between land and water, trade warfare crosses a similar border between military and civilian shipping. In many Western militaries, a Marine Corps is responsible for amphibious doctrine, training, the bureaucratic struggle for dedicated resources and fostering a distinctive culture that attracts motivated and skilled personnel. Likewise, trade warfare needs its own warriors, component command, doctrine and resources.

To improve operational effectiveness and organizational standing, a Joint Force Maritime Trade Component (JFMTC) should be established within Western military organizations. The primary aim of this organization would be to enhance command and control in directing multi-national joint forces, other governmental agencies and commercial actors for maritime trade protection. Though not a new idea, time is pressing to bring it to fruition. The new component command should synthesize a mix of military and civilian professionals from different warfare areas (maritime, air, cyber), from different academic disciplines (strategy, policy, economics, law, history) and from different entities (government, shipping industry). The JFMTC should take the lead in formulating new trade warfare doctrine and practicing the doctrine in training. This new doctrine should build on trade warfare lessons from the past and table top exercises of future conflicts. Also, a much wider trade warfare lens should be used than, for example, in current NCAGS doctrine. It should also encompass experiences in Maritime Interdiction Operations and Counter-Piracy operations. Furthermore, the attack on shipping needs to be studied, and even be practiced in exercises, to be able to develop effective counter-tactics and strategies. Trade protection does not exist in isolation: it is a reaction to the prospects of attack. Ignoring the offensive aspects of trade warfare, especially the impact of current and future technology, is a recipe for failing trade protection when push comes to shove.

CONCLUSION

The English adventurer Sir Walter Raleigh wrote: “Whosoever commands the sea, commands the trade. Whosoever commands the trade of the world commands the riches of the world, and consequently the world itself.” While Western ability to command the trade has dwindled, the secure flow of trade is still paramount for a free and prospering world in twenty-first century. This article has explored the causes of the Western neglect of maritime trade protection and shown that the trends in globalization, the shipping industry and navies do not justify this neglect. In fact, in the current, globalized world, the inability to protect maritime trade, a traditional core mission of almost every ocean-going navy, creates serious strategic risk. The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the critical vulnerabilities of a globalized, just-in-time economy, as supply and demand shocks caused global panic and most likely set the stage for a severe economic depression. Maritime trade forms the vital link between supply and demand. Commercial shipping is not only the driver of worldwide prosperity, but also a prerequisite for many military operations by providing sealift. While merchant fleets have grown in size, Western naval fleets have diminished in hull numbers, thus weakening their ability to provide protection across the wide ocean commons. At the same time, the return of geostrategic state competition, new technology and outdated international law form a recipe for a potentially disastrous maritime trade war.

It appears that the causes of Western neglect of the protection of shipping run far deeper than the apparent end of the Cold War and the consequent demise of the Soviet threat to shipping. The neglect of formulating an effective trade protection policy can not only be explained by the misperception of potential threats and the indifference to the strategic importance of commercial shipping; its causes are also rooted in culture, ideology and the sheer complexity of the issue. Many civil and military actors, each with their own cultural and ideological biases, are involved in developing and executing trade protection policy. It seems to be everyone’s problem, but nobody’s job, although it should be a core responsibility for navies. IR theory further explains the different views on trade protection. While Liberals prefer international law and economic benefits to direct behavior of other states, Realists prefer deterrence and offensive naval means. History shows that multiple trade protection measures are usually needed, both offensive and defensive. Furthermore, Constructivism suggests that Western states should foster their seapower identity and address current sea blindness within their societies. Hopefully the theoretical Trade Protection Policy Model explains the dynamics that drive and shape the process of formulating trade protection policy. The five questions derived from it offer a concrete, step-by-step method to develop a comprehensive trade protection strategy, involving all instruments of power. Furthermore, for the military domain, a Joint Force Maritime Trade Component should be established to take up the responsibility of trade warfare issues. It’s time to stop neglecting maritime trade protection and relearn the lessons that in past conflicts were provided at heavy cost in lives and resources.

Biographical note