Contents:

Introduction

The Historical Context

Stockton and Mahan

Afterthoughts

Kenneth C. Wenzer

Independent Historian

Introduction

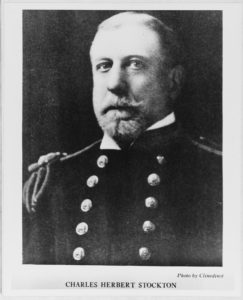

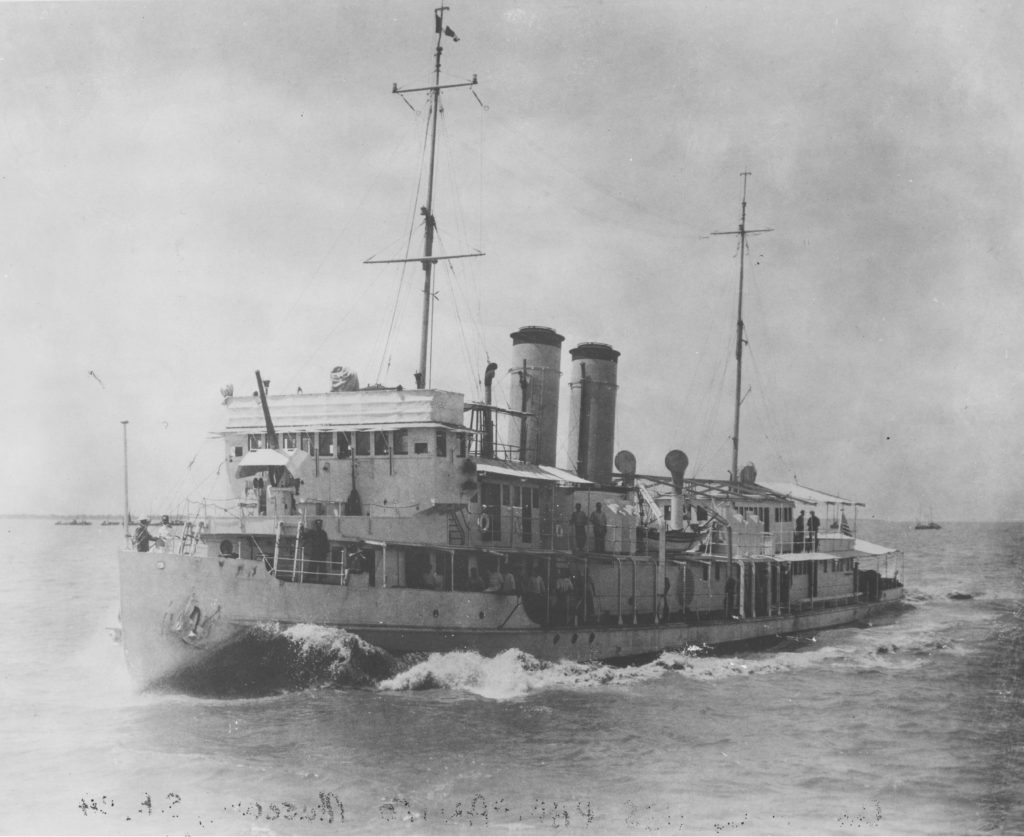

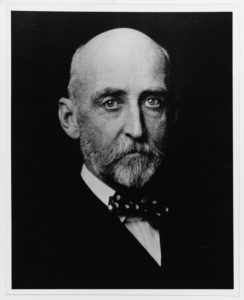

(NHHC Photo #NH 65840)

In 1513 Vasco Núñez de Balboa claimed the entire Pacific and all the shores washed by its waters for the Spanish Empire. Three hundred and seventy-four years later, in 1887, Lt. Cmdr. Charles H. Stockton of the United States Naval War College showed his students how to conquer this domain. The core of his plan envisioned Columbia, with drawn sword and shield, steaming up the Pacific Coast to attack Britannia in western Canada. The ultimate goal, of course, was to dominate trade in the entire Pacific Basin. There was one little detail that could have impeded this coup de grace since “until the end of the decade there was for all practical purposes no American navy.” The Royal Navy was, after all, a bit more robust.

The image of Stockton is different than that of Alfred T. Mahan, although he too was engaged in equally serious studies. Stockton’s strategic contributions, moreover, are undeservedly regarded as simulacra of Mahan’s. The Lt. Commander’s plan is noteworthy of discussion, for it is American chutzpa at its finest.

The Historical Context

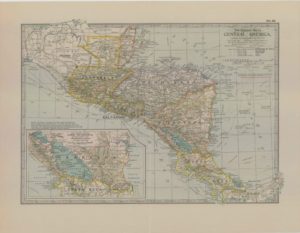

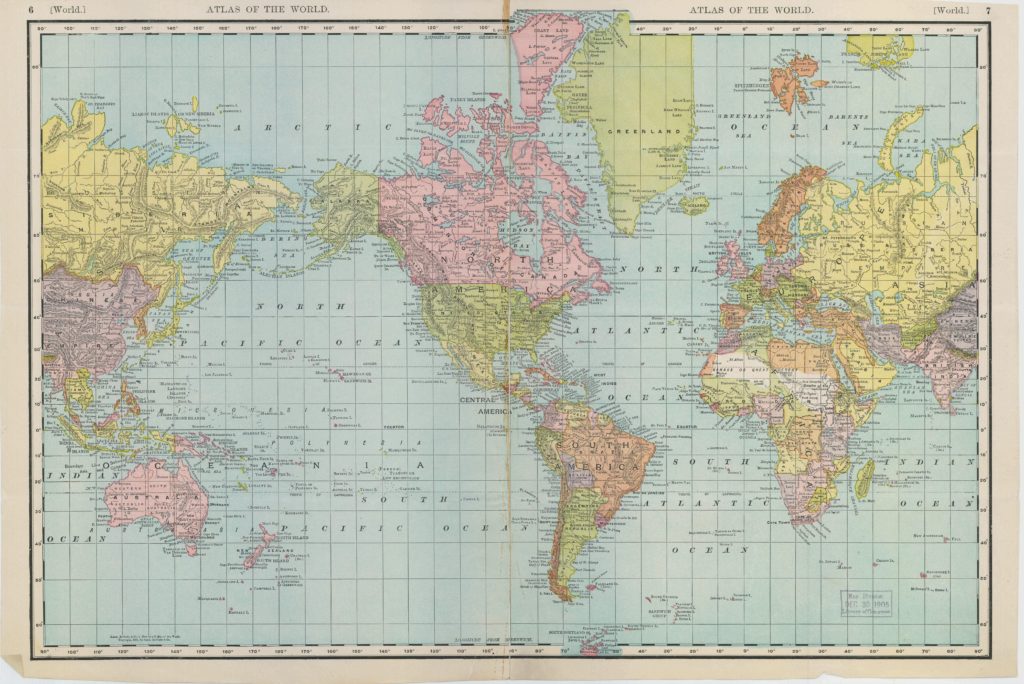

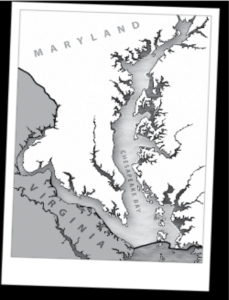

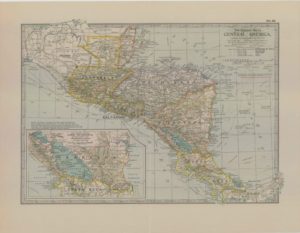

(Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress)

In nineteenth-century America travel by land was difficult and partially solved by the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Commercial and political interests, nevertheless, covetously looked towards the Central American Isthmus for the most cost and time-effective solution even before this event. The digging of a canal, tied in with manifest destiny, the Monroe Doctrine, and the dollar, in due course, became a major issue in the United States after the War of Secession. It attracted politicians of opposing camps and nudged by the U.S. Navy’s growing pains, fostered a collective impatience. In short, financial and naval policies coalesced, so then commercial and war strategies flowed together. The promise of an interoceanic canal beckoned with endless opportunities. In his pioneering work The Naval Aristocracy Peter Karsten wrote that the U.S. Navy arrogated “unique” duties in Central America since American business and political interests desired a canal. To that end many survey expeditions under the auspices of naval officers trekked through this area.

Both Panama (New Granada) and Nicaragua were the foci of these surveys, yet the latter, deemed more favorable, since it was more cost-effective, easier to tackle, and held forth a projected quicker schedule. The first American explorations in these areas, most of them government sponsored, began in 1852 and carried on into the 1890s. Besides surveying expeditions the Navy landed armed forces to pacify the isthmus. In 1856 Commodore William Mervine led the first sortie; it was followed by five other incursions up to 1884. Lt. Cmdr. Bowman H. McCalla’s takeover of a Panamanian town in 1885, however, was the most conspicuous for its flagrant audacity.

Ferdinand de Lesseps, the conqueror of the Suez, meanwhile, felt impelled to dig a canal without locks, this time in Panama. Agitated by this impending foreign intrusion, President Rutherford B. Hayes in a speech of 1880 firmly called for American predominance on the isthmus. After the French started digging in Panama in 1884, the U.S. Navy maintained a vigilant eye on their progress. They failed to overcome the terrain and involvement in multiple scandals resulted in bankruptcy by the end of the decade. Their impudence fostered an additional impetus for favoring the Nicaraguan route in Washington. Since commercial interests stormed Capitol Hill, Congress finally blessed the Maritime Canal Company of Nicaragua.

This upsurge of exuberance impelled men to realize that a viable navy was necessary to protect the anticipated commercial and even territorial conquests. RAdm. Stephen B. Luce, the founder of the Naval War College, gave credence to all these efforts. He extolled the virtues, both martial and transcendent, of an American future in an article “The Benefits of War” that appeared in the North American Review in 1891.

The First American Global Geopolitical Strategic Plan

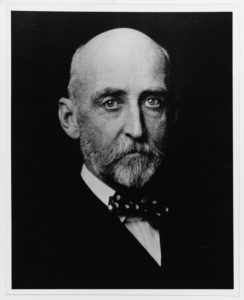

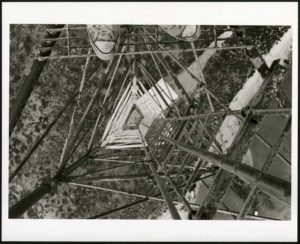

(NHHC Photo # NH 48053)

Capt. Alfred T. Mahan, the president of the Naval War College, wrote in his annual report to the secretary of the navy in 1887 that “much new matter has been introduced, all bearing upon the practical question of carrying on naval war to the best advantage.” That, of course, is an understatement, since it referred not only to his contributions but also to those of Lt. Cmdr. Stockton.

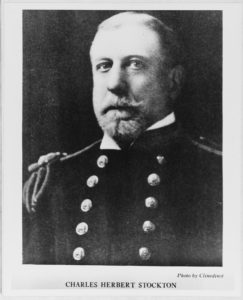

Charles Herbert Stockton, born on October 13, 1845 in Philadelphia, died in the nation’s capital on May 31, 1924. After graduating from the Naval Academy in 1865 he climbed through the ranks to retire as Rear Admiral. He served twice as president of the Naval War College and subsequently as president of George Washington University. Not only did he earn his sea legs on numerous occasions, but he also became the Navy’s leading expert in international law and contributed to an array of specialized fields with a voluminous output of writings.

Stockton’s series of lectures entitled “The Present Condition of Commerce and Commercial Routes Between Europe and the Pacific, with an Estimate of the Effect Produced on Them by a Trans-Isthmian Canal Including a View of the Military and Political Conditions of the Pacific Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean Sea: Military and Commercial Examination of the Port and Countries of the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea” ranks as his magnum opus. The first three lectures, including the introductory contains the first war plan against Spain composed at the Naval War College.

Stockton’s grand strategy focused on the completion of an interoceanic isthmian canal, whether in Panama or Nicaragua. His concerns centered on the undoubted commercial largess, with the shift and growth in trade that it would generate, and the myriad of benefits that would accrue to the American people. “Among the trade points upon the world’s surface,” he stressed, “the Isthmus and Gulf of Panama may be classed as among the very first in importance.”

Stockton anticipated that a canal, especially across Panama held superior military advantages over Nicaragua given its topographical and locational factors for more facile defensive and offensive operations. Such prospects should alert Americans to the poor state of naval and military preparedness that was necessary for the increase of global power with the entailed responsibilities. Lectures two and three pointed out that all of the canal’s eastern approaches and strategic points in the Gulf of Mexico and the West Indies should be not only readily defended, but also dominated by the United States. The Caribbean, in short, should be transformed into an American pond.

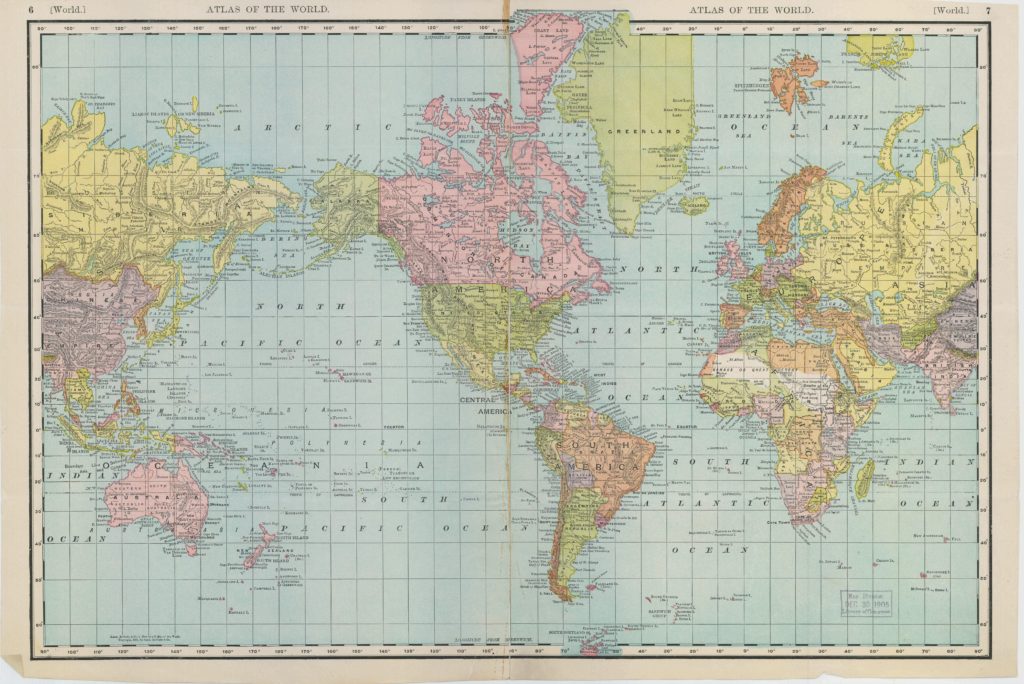

In lectures seven and eight Stockton also foresaw major alterations in trade routes west of the canal—in the Pacific. They were, of course, in his mind indistinguishable from military routes, so they came under his scrutiny.

Before proceeding with the gist of the lecture, Stockton exhorted his students about the globally inexperienced military, especially the Navy beset by its’ precarious and miniscule state. The U.S. faced an unexpected new problem while looking inward with its expansive industrialization and growing internal unity. Washington had neglected to prepare for challenges posed by foreign powers. A mental and physical laxness had been generated. “The great nations,” he wrote

in the art of war have announced as an axiom that of all things which contribute most directly and effectually to the success of a military undertaking, preparation holds first place . . . . It has been said that great states which have risen out of chaos require time to consolidate and organize themselves; their whole power and energy being chiefly directed toward that point. Driving this period of consolidation and organization their foreign wars are few, and the wars that do take place bear the stamp of a state unity not well connected.

Given the chronic clash of global interests one must regard the oceans as the future battlegrounds. The arsenals and dockyards will be the armed camps and bases of operations, and the coaling stations will be the “outposts in these areas of future campaigns and fields of coming strategy.” It was therefore important to be vigilant, for

With the new period about beginning will come a conflict of interests—first with other powers in respect to the new interests upon the American Continent, and secondly with other great powers in regard to our growing and antagonistic interests in the great field of the world . . . . the work of preparation should now go on.

And Stockton emphasized, that the “duty of performing this [work], which included a knowledge of the art and practice of war, especially naval war, for which this College was instituted, belongs to us.”

The astute officer, according to Stockton, should not only concentrate on the immediate firepower of the Navy’s ships but the myriad of other important issues that make for effective nautical maneuvering. “So much is involved in this question of docking,” for instance, “that I cannot resist calling attention for a moment to its connection with Naval strategical [sic] questions.” The “creation of speed” for a fighting fleet, Stockton continued, had been given ample attention, but he forewarned, that the maintenance of this speed will be quickly hampered by the fouling of bottoms with increased coal consumption. These issues, however, have been ignored. Basic concerns, such as naval bases, arsenals, and coaling stations have likewise met the same fate. Greater funding was therefore a prime requisite for a fit navy.

If the vanguard of America’s military and commercial future belonged to an energetic officer corps, so as a matter of course, the future canal would be the key to open this vision. Since the strategic and logistic focus would be Central America it was to be the prime target of any enemy.

The French could be overcome with exertions in the Caribbean and the Pacific, but the Spanish, Stockton thought, could be easily eliminated as evinced by his war plan against Cuba. When Stockton first began writing his lectures as early as 1886 he also displayed a fear of German commercial growth in Central America and the Pacific. He believed this activity would attract settlers, foster territorial aggrandizement, and undoubtedly be followed by a military presence. Since this German incursion was repugnant to his growing country, they had to be addressed.

German trade and German merchants have increased greatly of late years. . . . we will meet the German in his merchant capacity, backed by the forces of his country, at various times and places . . . His success has been remarkable of late years in almost every civilized and semi-civilized country of the world and he is becoming a great and successful rival in many places to the English merchant who has been for years, par excellence, the trader of the world.

The foreign bases eastward, especially at Port Royal in Jamaica, Havana in Cuba, and Fort de France in Martinique were major threats. The potential westward points, such as the Galapagos, could in all likelihood serve as a rallying point to marshal forces against the canal. On the other hand, the canal could be the prime U.S. base against Europeans. Their future military activity in Latin America, on both its Pacific and Caribbean shorelines would be forestalled. The subjugation of Mexico could also be orchestrated.

So the isthmus at either the Nicaraguan or Panamanian locations on both oceans, with their different logistic and strategic defensive and offensive locations, necessitated protection by both the Navy and the Army.

The Canal once in possession of the [American] Naval forces should be held by both a force afloat and ashore and all exposed points [and] locks [should] be securely watched. The canal could then if necessary be used as a base of operations against any hostile forces on the Isthmus on either side of the Canal.

Whereas Havana presented the most important strategic position in the Gulf of Mexico and the West Indies, San Francisco held the same significance for the entire Pacific Ocean. To that end, he expatiated on the strategic features, both defensive and offensive capabilities of various points on the U.S. Pacific Coast. He delineated the present and potential trade routes that would alter and bloom with the completion of the canal. He also discussed the abundance of natural products, the richness of minerals, and even the importance of a potential source of motive power in his coal-fired steam age.

If petroleum which seems to be the possible fuel of the future, should become a practical success in this respect in our day, Southern California would present in [the] future greater naval advantages and independence of resources, than now, there being a pipeline to the seaboard existing for the purpose of carrying the oil, which apparently abounds in this section. This would compensate for the absence of coal.

With the opening of the canal, San Francisco, with its capacious harbor, was to coalesce all these natural and man-made elements. Its fate was to become an awe-inspiring world metropolis. Stockton’s enthusiasm was exuberant: “with free and direct trade to and from the Atlantic will [also] come great distributing trade to this city not only for the Pacific slope, but for the island world of the Pacific Ocean. The closer proximity to European and to our own Eastern markets will give it a position of advantage beyond any attainable by other ports in the Southern Hemisphere.” It’s harbor and dry-dock facilities, communications facilities, and transportation access to the interior with its rich natural resources were unequalled on the entire Pacific coasts of both hemispheres. Blessed by geography, San Francisco

is now the only naval station of the United States upon the Pacific . . . . The United States have the best position upon the Pacific as a whole in regard to the [the] future and material resources, and preeminently the best upon the Northern Pacific.

Since the paramount commercial and strategic importance of San Francisco was undisputed, it would be the natural target of foreign nations that are vying for power in the Pacific.

The English in the Western Hemisphere and the Pacific, with their greater presence, were the most formidable commercial rival of the United States. Stockton’s fears, therefore, focused on Esquimalt, a British naval base located on Vancouver Island. It was poised like “a spearhead thrust at our Northwestern frontier” and all points southward, especially San Francisco. It was also within reasonable steaming distance of the projected canal. Esquimalt presented the greatest threat, for this base could easily draw on Canada’s many natural bounties to attack San Francisco. America’s military presence on the western shores was dolefully inefficient, so

with a loss of . . . [an] engagement would cease our trade along the coast would follow a general commercial paralysis on our Pacific Coast, the smaller towns and harbors would be subject to capture or tribute and the Enemy at leisure could blockade San Francisco or begin elaborate preparation for its attack by land or sea.

Stockton’s solution was to establish a naval base in the Northwest to initiate an aggressive offensive and establish defensive countermoves. A naval presence in Puget Sound would therefore be America’s first line of protection with the marshaling of every available resource, where “the fate of San Francisco” would be decided, especially with this city’s lack of coal. The Northwest, however, was a region blessed not only with coal and timber, but also of outstanding rail transportation that crossed the continent. In all likelihood British incursions would primarily be naval without major troop support. “Its resources making it to an enemy like Great Britain, a rich and tempting prize, subject in war to attack.”

Stockton described in painstaking topographical and hydrographical detail the respective British and American positions on Vancouver Island and Puget Sound. The lieutenant commander also pointed out the lines of defense, fortifications, and locations of naval bases that would have to be established under different circumstances of enemy action, given the tides, time of day, and weather.

With a naval base in Puget Sound to “counteract” the British presence, communications would also be maintained with Alaska and the entire Pacific coastline protected.

We are now separated from this portion of our domain by 500 miles of water navigation and by territory belonging to the strongest naval power of the world. If we should be at war with another country besides Great Britain, we could not expect in the light of our past experience much benevolent neutrality in the ports of our neighbors in British Columbia . . . . Esquimalt[‘s] . . . existence and resources are menaces to our interests in this part of the coast and Pacific Ocean.

Stockton showed his concerns, especially with the growing city of Vancouver as a supply center and its proximity to Esquimalt. Its political isolation was about to end with closer ties to Halifax and Great Britain thanks to the Canadian Pacific Railroad. Stockton deemed it “the great military highway of British America.” Most assuredly the area’s strategic importance would grow. And in passing he bemoaned that the absorption of British Columbia by the U.S. would be postponed. He then prophesied momentous consequences:

It is my belief . . .that in case of war with Great Britain the theatre of naval war in the Pacific will be here . . . .

We should have our strongest naval forces concentrated at these points for purposes of the defensive and for the purposes of that offensive, which the genius and spirit of our people naturally desire.”

The base at Esquimalt intimidated Stockton. He described in detail its harbor soundings, port facilities, dry-dock capacity, number of vessels, fortifications, lines of defense, strategic points, rail connections and access to bituminous coal and other natural resources. In short, this base commanded, with its great resources and associated rail transportation, the Canadian and American waters in the region, so it was a menace to the Pacific Coast and trade.

Stockton believed that there was only one way to permanently eliminate the British—to launch an aggressive and incisive campaign against western Canada. An initial raid with troops conveyed by light-draft steamers against the rail lines would be advisable. A blockade would also be initiated at Esquimalt and other strategic points and harbors; and then the enemy’s ships could be forced by the fleet, or enticed into an open engagement depending on the land defenses. If certain places were too strong then there would be alternative operations. Vancouver and other towns should then be subdued. Major efforts at all costs should be made to keep the Royal Navy from attacking the American coastline. The vast human resources of the United States, at any rate, could be mustered against the British forces hampered by a sparser population in western Canada.

Stockton’s vision also reached across the expanses of the Pacific Ocean, most especially New Zealand and Australia. In his estimation, the Pacific belonged to “the domain of the American canal,” as did most of its islands, since they would be focal points for trade from it. The Suez Canal with closer ties to European and U.S. eastern markets would also be enhanced. They were, along with Hong Kong, however, controlled by Great Britain. They were deleterious to the United States, for they were home to numerous war vessels.

So Stockton stressed the importance of New Zealand and Australia. New Zealand presented a potential threat to U.S. interests for its logistical position as a coaling base and many fine harbors, some of which were strongly fortified. Blessed with bountiful natural resources, the latter boasted the capacious harbor of Sydney. London had poured money into the populated areas for defense. In addition to the Royal Navy, the Australians maintained local squadrons, so as to contribute to a maritime and naval superiority in the southern Pacific area.

To counter these threats, as with Esquimalt, Stockton proposed two major aggressive operations.

Any naval operations against New Zealand would naturally be directed first against Auckland and on account of its fine harbor and strategical [sic] position. . . .

with a moderately strong force it could be taken and held until the combined Australian squadron should appear. Single vessels, unarmored, could be denied anchorage but could find in the Bay of Islands a temporary rendezvous for operations against the shipping [in the area]. . . .

While operations in New Zealand were carried out, American forces should also launch

An attack upon Sydney in Australia [and it] must be a formidable one as the harbor is strongly fortified and in addition . . . a strong naval force is sure to [be] met with here. Some point held in New Zealand like Auckland or the Bay of Islands would be the best base of operations against Sydney . . . . [There are also ample landing places for troops and harbors of refuge.] The naval forces of Great Britain, which would assemble in Australian waters must be met and defeated . . . .

Stockton was fearful lest the Royal Navy could dispatch its Pacific squadrons to the Hawaiian Islands. As a base of operations these vessels could meet with their sister ships from Esquimalt in the northern Pacific waters. They would form a formidable fleet against the coastline of the United States and commercial routes. These islands could also be used as a coal base since they were situated at the “crossroads” of the seas with close ties to San Francisco. Hawaii should be, therefore, owned by the U.S., otherwise control of the northern and mid-Pacific would be forfeited, for

it is not likely that this group will used as a primary base by the naval forces of a nation not holding sovereignty over this group. The group would prove an important port of call for vessels or squadrons from Australian and Chinese waters who could here unite and reach by economical steaming Esquimalt on Vancouver Island especially if they did not fear an enemy of equal or nearly equal force when they approached that vicinity.

France, however, could potentially be a secondary threat with its possessions in the mid-Pacific, so he proposed operations against Tahiti. Stockton also thought that assaults against Chile and Peru should be launched. A number of points on the west coast of South America could be taken for their strategic value on the southern approaches to the proposed canal. Stockton cursorily discussed the Russian presence at Vladivostok, but he dismissed this empire.

He pointed out, nevertheless, that there could be the possibility of campaigns against the Japanese, Chinese, Hong Kong, and the Philippines. He, however, thought it more prudent to concentrate on the northern and mid-Pacific regions. The entire Pacific including Central and South America, should be dotted with coaling and naval bases, that could be used as launching points of operations against enemies. They would, of course, serve as protection for the U.S. controlled canal. Stockton also suggested that there should be no territorial aggrandizement.

We should construe these intended pan-Pacific operations and plans as the first Naval War College attempt at global strategic thought—Stockton, did after all, insist on the “domination of the whole of the Pacific Ocean.” His broad-sweeping vision of an expansive America did seem to reflect the growing aspirations of the naval officer corps.

Stockton composed his “labor of love,” in part, as an entreaty to his fellow officers and ultimately countrymen, so they would become aware of their vulnerability in a world beset with change. He naturally referred on different occasions to the parlous state of the U.S. Navy while inculcating his students at the Naval War College that

To accomplish the destruction of . . . [the enemy’s] naval force we need not only a force large enough in numbers to meet any fleet Great Britain would be likely to assemble here, but also one including battleships, carrying ordnance of large size and modern construction and protected with heavy armor . . . .

No matter how brave and efficient our officers and men will be, a loss of moral force is inevitably connected with the consciousness of inferiority in force, in protection in the number of vessels. The spirit of courage is transferred to be simply an endurance of a cruel punishment.

Lt. Cmdr. Stockton looked at tackling the isthmian canal much as a boy with open eyes watched a space capsule sail to the moon. Both were the exertions of Americans sharing pride in the quickened activity of a proud country that offered promise, a nation straining, both brain and muscles, to achieve the dreams of decades. He concluded his first lecture in the following fashion:

the successful completion of the ship canal between the two great oceans of the world, it is not too difficult to see that, with its opening, a great epoch in the commercial history of the world will be begun. The importance of the work to the United States can hardly [be] estimated.

Stockton was the first naval officer, with pencil and paper, to chart the bounteous future that the canal promised, and he did so on a global basis. Strategic Study of Lake Frontier of the United States” during the same session as Stockton’s lectures. See: Mahan, “Report of President of Naval War College,” Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1888 (WDC: GPO, 188), 101. Given the small staff at the Naval War College Stockton and Rogers undoubtedly knew each other. It is also possible that they envisioned orchestrated assaults on east and west Canada, but additional research is necessary. Mahan was also familiar with Rogers’ war plans.

C.C. Rogers tells me that the “Intelligence Report on War Resources of Canada” has not yet been forwarded by the Admiral [David D. Porter], and that if he can be allowed to retain it, he can, without further writing, read from it such parts as may be necessary for our lectures on the “Strategic features of the Canada frontier”. . . . [Mahan to Raymond P. Rogers, 13 August 1888, as presented in: Robert Seager, II and Doris D. Maguire, Letters and Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan, Vol. I: 1847-1889 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1975), 656.]] That should make us aware of three more lost traits—an untrammelled innocence yet one that faces reality, a thirst for learning yet an awareness of a changing world, and a unique yet shared vision—hallmarks that suggest an original thinker.

Stockton and Mahan

Since we are exploring nineteenth-century American naval history, it now seems appropriate to invoke Capt. Alfred Thayer Mahan. At the age of forty-five and while wearing an officers’ uniform, he was apparently an avowed anti-imperialist who “looked upon Mr. Blaine (the secretary of state in the Harrison administration) as a dangerous man” for his acquisitiveness. We should then excuse Mahan for his untutored lapse while “drifting on the lines of simple respectability as aimlessly as one very well could.”

Later on, in 1887, after apparently “seeing the light,” Mahan made his new revelations known in a series of three lectures at the Naval War College collectively entitled “Naval Strategy and the Strategic Features of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea.” The next year he again gave “The Strategic Features of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea” series. The exact original contents of these lectures are not known since they are not available. These titles do suggest that the Pacific was in all likelihood not mentioned, although he was aware of the potential of an isthmian canal and its relationship to the Caribbean.

Mahan’s initial lectures, meanwhile, were received quickly and enthusiastically by his fellow naval officers in the late 1880s, so his reputation began to soar, even before his public presentations on the Caribbean and isthmian issues. McCalla, who displayed exuberance on land and on deck, was also apparently given to a scholarly bent. In a letter to Luce, he wrote that

It is very pleasant to hear you speak in such enthusiastic terms as to the ultimate success of the War College. I am happy that Mahan’s lectures have been such a success. I know that he is a man that reads a great deal and would be very likely to give papers indicative of great research.

But it was not these lectures that made Mahan famous. It was the eternal principles set forth in his blockbuster The Influence of Sea Power Upon History in 1890. Robert Seager points out, however, that they were “borrowed.” Ens. William G. David published an article “Our Merchant Marine: The Causes of Its Decline, and the Means to be Taken for Its Revival” eight years earlier in the Proceedings of the U.S. Naval Institute. In 1882 David detailed in embryonic form a “few general conclusions [that] may be drawn from. . . [a] review of the six great sea-powers of the past.” They bear a striking resemblance to Mahan’s paradigmatic cornerstones that influence sea power in his famous work.

David was not the only man from whom the busy Mahan eventually “drew inspiration.” Stockton’s lectures on the Pacific were also cornucopian sources, for Mahan neglected to take into account the entire Pacific Ocean in his strategic thinking until the same year as The Influence of Sea Power upon History. If we look at Mahan’s articles before the Spanish-American War, there are four that draw our attention.

“The United States Looking Outward” first published by the Atlantic Monthly in 1890 depended on Stockton’s Pacific lectures. In this article Mahan regarded the Hawaiian Islands as necessary to American strategic interests and was fearful of aggressive German commercial growth. He pointed out the strength of Great Britain and the importance of western Canada and its vulnerability. The isthmian canal, moreover, will alter trade routes. The U.S. Pacific Coast will be exposed to attack, so San Francisco and the Puget Sound took on greater importance, and they will need protection. All these thoughts sound familiar and now Mahan lauds Blaine as a harbinger of imperialism.

Three years later the article “Hawaii and Our Future Sea Power” was published in the March issue of the Forum. It too seems to be an echo of Stockton’s concern for these important islands, especially with their strategic position for control of the North Pacific. Mahan was concerned, however, about forestalling the spread of Oriental barbarism. The newly found American “maturity” regarding Pacific conquest was also a factor. Concern was shown for the presence of the British on both sides of this ocean with well-positioned strategic points at the opposite shores in British Columbia, and Australia and New Zealand; and of course their covetous desire for Hawaii, well within steaming distance of the U.S. The proposed isthmian canal would naturally open the Pacific to American commerce, and Hawaii would be a crucial key to its security.

Six months transpired, then “The Isthmus and Sea Power” appeared in the September 1893 issue of the Atlantic Monthly. The only mention of the Pacific is a passing remark about how the isthmian canal would bring the two coasts of America closer together and enhance trade for the western states.

“The Strategic Features of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea,” published in 1897 by Harper’s Monthly, is strikingly silent about the Pacific in its contents, but highlights the Caribbean as the center of American sea power. Although the proposed canal would be an important link, “the maritime routes in the Pacific converging upon the Isthmus—do not concern us.”

(Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress)

Then after the Spanish-American War additional articles and books related to the Pacific most assuredly came to light.

One noteworthy work in this latter period, Naval Strategy, is worth examining. If we read Mahan’s 1911 lecture series that appeared we find that his earlier Naval War College talks, as mentioned above, were reedited. His major thrust can be found in the following lines:

While the Monroe Doctrine was the sole positive external policy of the United States, as contrasted with the negative policy of keeping clear of entanglements with foreign states, national interest gradually but rapidly concentrated about the Caribbean sea; because through it lie the approaches to the Isthmus of Panama, the place where the Monroe Doctrine focuses.

Mahan’s wisdom of hindsight was marvelous. With some early nurturing by Stockton’s focus on the Pacific, the ongoing interest in the canal, the stark implications of growing American, Japanese, and German power, and the Open Door Policy Mahan’s thinking undoubtedly matured. Then of course there was always the enlightenment for his reading public.

The Pacific possesses an actual immediate importance . . . . the Caribbean remains important; perhaps it has not even quite lost the lead, but it is balanced by the Pacific. The approaching completion of the Panama Canal will bring the two into such close connection that the selected ports of both obviously can and should form a well-considered system, in which the facilities and endurance of each part shall be proportional to its relations to the whole.

The two chapters, eleven and twelve in his Naval Strategy devoted to the Gulf of Mexico and the West Indies, respectively entitled “Application to the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea” and “The Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea,” ignore the Pacific, except in rare instances, and then only in passing. They contained newer material with his twenty-four years of reflection. Mahan ends chapter twelve with the pronouncement that the Caribbean is “the strategic key to the two great oceans,” without mentioning the Pacific waters that embrace four continents with its countless islands.

Mahan, however, did justify his lack of focus since the possibility of American influence across the Pacific in the 1880s was not visible on his remote horizon. He pointed out that: “This was the condition when these lectures were first written. The question of the Pacific and its particular international bearings was then barely foreshadowed and drew little attention.” This statement is quite striking given Stockton’s labors. One astute historian wrote, that

the Panamanian isthmus was vital because many American citizens and large quantities of American merchandise annually traversed the narrow passage. The southern regions of Central America . . . held the key to a flourishing intercoastal and international American trade. It was therefore considered essential that the United States have a dominant voice in isthmian affairs.

Mahan, nevertheless, stressed the importance of the canal in a concise synopsis in his report to the secretary of the navy for 1887.

The consideration of the results of an isthmian canal is designed to familiarize the minds of officers with the great issues that are maturing in the waters of Central America; the importance of those regions with the point of view of military control, if not of war; and also incidental to awaken attention to the close attention between the commerce and naval interests of a country.

So Mahan was keenly aware of the strategic and commercial implications of an isthmian canal, but apparently not for the consequences of a bounteous role for Pacific trade and the potential tasks for the U.S. Navy. He was too Euro-centered and parochial in his thinking, so he clung to the Mediterranean as a reflection of history. In short, he looked to the past instead of to the future.

What Mahan claimed to be of no importance in the 1880s over two decades before this updated lecture of 1911 and his earlier articles, Lt. Cmdr. Charles H. Stockton addressed with vigor, while berthing with his soon-to-be famous colleague at the Naval War College in 1887. As the evidence suggests Mahan‘s strategic concerns for the Pacific did not become apparent until after Stockton’s presentation. Should we then accept Mahan’s boast that “the light dawned first on my inner consciousness; [and] I owed it to no other man.”

Afterthoughts

Research in public and private collections has thus far indicated that Stockton’s name

is conspicuously absent in documents for this period. He, for the present, remains an enigma. His voluminous works, however, bespeak of an industrious man. It is “The Present Condition of Commerce and Commercial Routes Between Europe and the Pacific, with an Estimate of the Effect Produced on Them by a Trans-Isthmian Canal . . . ” that will remain his monument.

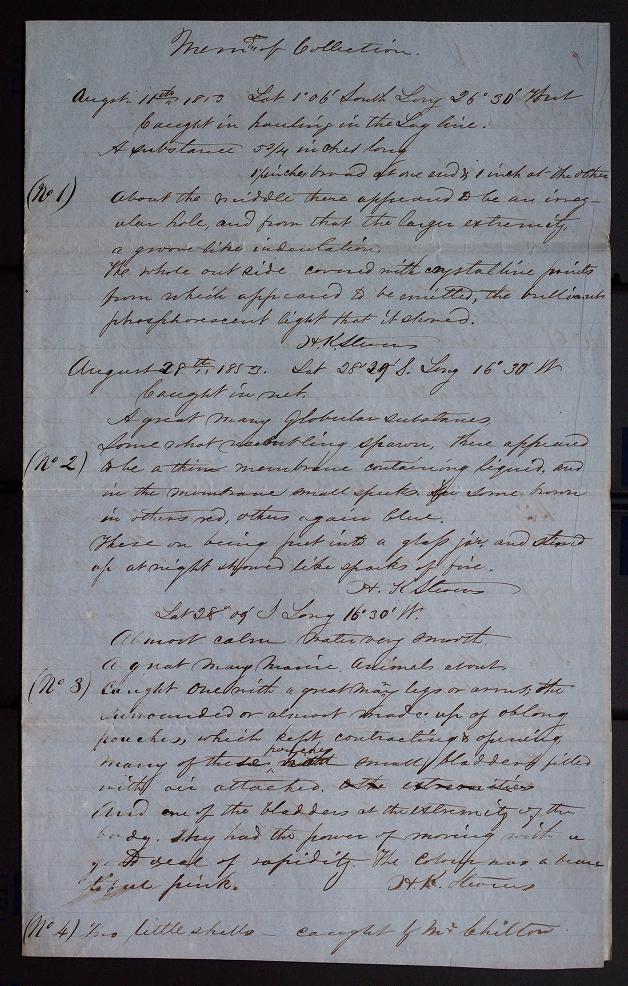

Some inconsistencies in the Stockton manuscript, nevertheless, should be addressed. The introduction is located in a separate folder from the truncated major work that is missing some lectures, so it was possible that there were also a number of redactions. Mahan’s “Report of President of Naval War College” in the Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy for the Year 1887 mentioned six lectures, but they were not itemized. Stockton’s introduction, which served as lecture one and as an overview for the entire series, indicated only five. They were described in the following manner:

The first lecture besides being introductory in its nature will treat especially of trade and trade routes now existing between the Atlantic and Pacific, showing how both will be effected by the Canal.

The second and third lectures will embrace a naval and commercial examination of those ports and harbors of the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea, that are important in a military or commercial sense, with respect to the trade routes to the Canal and the Canal itself.

The fourth lecture embraces an inquiry into the political state of the Central American countries likely to be most affected by the canal, and a narration of the international questions bearing upon the Canal.

The fifth and final lecture will give the general conclusions derived from the preceding lectures accompanied with a general discussion of the Canal question as it affects the Pacific and how it bears in its different aspects towards the United States.

In an earlier article this author touched on lecture one and discussed lectures two and three, with an emphasis on his war plan with Spain found in the latter two. Lectures four and five are missing from the Naval War College Archives and so was a surmised lecture six. Lectures seven and eight were undoubtedly a later product, most likely from the next year, and as cited in Stockton’s notations, were respectively: “A Strategic Study of the Pacific Coast from the Gulf of Panama to British Columbia with Special Reference to the Interests of Military Policy of the United States” and “[A] Strategic Study of the Waters of Puget Sound and those Adjacent to British Columbia with a General Examination of the Strategic Conditions and Possibilities of the Pacific Ocean.” The struck-out words in the above block quote indicated that these subjects treated in lectures seven and eight were originally slated for lecture five.

In the Report of the Secretary of the Navy for 1888 Mahan informed Washington that Stockton prepared a course on the “commercial sea-routes and the strategic features of the Pacific coast of the United States.” The Report for 1892 noted that courses on “The Strategic Features of the Pacific” and the “Nicaragua Canal” were given, but without authorship.

Two years later Capt. Henry C. Taylor, the president of the Naval War College, thanked Stockton for assisting in the general preparations of the school. He noted that the “lectures of Commander Stockton were instructive in many ways, and especially impressive in a series on the Nicaragua Canal, indicating the effect of such a canal upon the naval policy of this country and upon various questions of strategy and tactics involved.”

If we leap to 1900 Stockton presented two lectures, one of which was the “Strategic Features of Our Northwest Coast, within the Range of the Problem.” Also in this same Report Assistant Secretary of the Navy Frank W. Hackett extolled the labors of the outgoing president: “The college has been fortunate, indeed, under the administration of Captain Stockton. This officer has not only inspired others with zeal for the work, but has himself contributed several papers of high professional value to the records of the college.”

Stockton’s lectures, both on the Caribbean and the Pacific, were written at the same time as Mahan’s inquiry into the strategic features of the Gulf Coast and the Caribbean Sea, and as adumbrated above, most assuredly antedated Mahan’s inquiries into the Pacific. Notations on the Naval War College folder that contained Stockton’s introduction suggested that his strategic lectures, or at least some of them, were read in 1887, 1888, and 1892. A revision was also indicated on June 9,1894 and another reading on July 23, 1894. The notations, however, did not suggest whether the Pacific or Caribbean lectures were read.

Apparently, Stockton kept the proposed canal close to his heart. A year after the Spanish-American War and just before his retirement as president of the Naval War College in 1900, the Proceedings published another article, “The American Interoceanic Canal: A Study of the Commercial, Naval and Political Conditions.” Although this re-casted and updated version conflated his original lectures and excised the war plans against Great Britain and Spain, his vision, nonetheless, remained unchanged.

The completion of a Ship Canal across the Central American isthmus, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, will undoubtedly mark an epoch in the history of the civilized world. . . . the trade of the American Canal should increase with great strides, accompanied as it will be with the increased population and development of the west coast of America, with the growth of United Australasia, and with the establishment of stability and trade relations in our new insular possessions in the Pacific and the East, as well as in China and Japan. . . . The command of the sea on our north Pacific coast and the waters of the western basin of the north Pacific should be in our hands in peace and war-time.

Stockton correctly surmised that the canal would engender new commercial and strategic rearrangements throughout the world.

The close relationship between Stockton and Stephen B. Luce endured for many years. In a letter dated February 6, 1888 the younger man wrote to his mentor.

It is pleasant to find the labor expended upon the lectures duly appreciated. So much of the matter existed in a widely scattered form that hard work was necessary to gather it, digest it and reason from it; so much chaff to go through with to get the grains of wheat.

The work, however, was a labor of love, and I feel indebted to the College for giving me a direct tangible reason undertaking the subject. . . .

I went to the College as its friend, but must admit returning from it as a partisan, and I hope never to miss an opportunity of saying a good word in its favor, in the proper season.

The U.S. Navy, with a little help on the Hill, carried out Stockton’s suggestion in his strategic plan to establish a presence in the Northwest. His letter continued, and with self-effacing modesty, reported that:

The Congressional Record of today shows an endeavor on my part to improve an opportunity in connection with Senator [John H.] Mitchell’s speech on a Puget Sound naval station. I wrote quite a letter in advocacy of the College; he has not incorporated it in his remarks, but it ought to have its effect upon the senator himself. He however though giving me the benefit of complimentary remarks, which I wanted for the War College shows the subject originated from the War College and its president and not from myself. Every little helps..]

During the same year as this Stockton missive, Mahan received orders from Secretary of the Navy William C. Whitney—his presidency of the Naval War College was terminated so he could reconnoiter for a new naval base in the state of Washington, while Stockton was faithfully by his side.

(Return to September 2018 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

Kenneth C. Wenzer is an independent historian. Gratitude is extended to Charles C. Chadbourn, III, editor, International Journal of Naval History, Scott Mobley, United States Naval Academy, Michael Crawford, Historian of the Navy, Paul S. Hoff (a great grandson of Stockton), Barbara Bull, Karin Anderson, and Norman G. Schneider. I am also indebted for the archival support and librarianship of Dara Baker and Scott Reilly, Naval Historical Collection, U.S. Naval War College (hereafter, NHC); Glenn Helm and his staff at the Navy Library; Jeffrey Flannery and his staff, Manuscript Reading Room of the Library of Congress (hereafter, LC); and Eric S. Van Slander, Christopher Killillay, and their colleagues, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. and College Park, MD. Spelling and grammatical discrepancies have, at times, been silently corrected and regularized in the primary, but not secondary source quotations. Washington, DC is abbreviated as “WDC,” New York City as “NYC,” Government Printing Office as “GPO,” Proceedings of the U.S. Naval Institute as “USNIP,” and International Journal of Naval History as “IJNH.”