Henrikki Tikkanen

Aalto University School of Business

Abstract

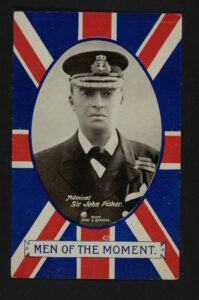

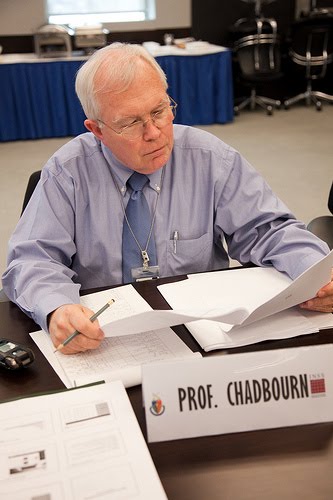

Admiral Sir John Fisher was the leading figure behind the considerable reforms that took place in the Royal Navy before and during the First World War. Britain was engaged in a costly naval arms race with Imperial Germany during the Fisher era of 1904-1919. The controversial admiral surrounded himself with a network of followers who were tangential to the success and continuation of many of his reforms. This network has been termed the ‘Fishpond’. It is often seen as a valuable resource for Fisher, enabling him to realize his organizational reforms. On the other hand, derogatory perspectives also prevail, as a ‘Syndicate of Discontent’ was formed to oppose Fisher’s designs. This article examines the role of the Fishpond in relation to the official institutions of the RN. Who were the most influential officers in the Fishpond and how did their careers evolve under Fisher’s patronage? What were their roles in carrying out Fisher’s reforms? Finally, how effective was the Fishpond in general as a ‘tool’ in the reform process of the RN, especially in the face of the fierce internal opposition to it?

HMS Britannia at Dartmouth (Wikimedia Commons)

Keywords

Naval history, Sir John Fisher, Fishpond, strategic leadership, the Royal Navy

Admiral of the Fleet Sir John Arbuthnot Fisher, 1st Baron Fisher of Kilverstone, (1841-1920) was the leading figure behind the considerable technological and organizational reforms that took place in the Royal Navy (RN) before and during the First World War (WWI). Britain was engaged in a costly naval arms race with Imperial Germany during the Fisher era of 1904-1919. The reforms he initiated have often been termed Sir John Fisher’s naval revolution , and a vivid historiographical debate has ensued as to the strategic emphasis, effectiveness and the role of Fisher himself in instituting the process of significant organizational change within the RN . Historiographical debates notwithstanding, Fisher served from 1886 to 1903 as Director of Naval Ordnance, Third Sea Lord and Controller, and Second Sea Lord, and as the Commander of the Mediterranean Fleet. In these positions, he could observe and occasionally compensate for the shortcomings in the materiel, education and manning of the fleet. More importantly, when he took over as First Sea Lord of the British Admiralty in October 1904 he was free to devise a much more ambitious and holistic scheme of reforms. During his first tenure as First Sea Lord in 1904-1910 he realized several major administrative and technological reforms. For instance, he introduced the Dreadnought model of powerful all-big-gun capital ships that made earlier capital-ship designs practically obsolete. He had a short second stint as First Sea Lord during the War in 1914-1915 when, among other things, he succeeded in re-commencing the construction of battlecruisers, his favourite design of capital ship.

However, as a leader Lord Fisher was a deeply controversial figure. Headstrong and visionary, occasionally petty and vindictive, he invoked both admiration and hatred among the officers of the RN. On the one hand, he was very effective in gathering a loyal network of followers from all walks of life in the British Empire to support his designs. This network extended within and beyond the ranks of the RN, and ranged from King Edward VII to some key politicians, courtiers and influential journalists. Fisher effectively used publicity and the media to advance his cause. More importantly, his network comprised some of the most talented officers of the RN who were essential to the success and continuation of many of his reforms. This coterie of more-or-less loyal followers has often been termed the ‘Fishpond’.

Nevertheless, a ‘Syndicate of Discontent’ formed around the disillusioned admirals Lord Charles Beresford and Reginald Custance during Fisher’s first period as First Sea Lord, fuelled by his ruthless ways of working. A ‘Great Edwardian Naval Feud’ ensued, seriously dividing the RN into two opposing camps. In 1909, Beresford succeeded in convincing Prime Minister H.H. Asquith that a formal inquiry would be needed to investigate some key Admiralty policies. Fisher emerged victorious from the inquiry, but he was practically forced to step down in January 1910. He continued in an advisory capacity and as a member of the Committee of Imperial Defence until his second period as First Sea Lord in 1914. After his unseemly resignation in May 1915 primarily due to the failed Dardanelles campaign, his influence swiftly declined. However, he continued to serve as the chairman of the Government’s Board of Invention and Research (B.I.R.). Other men, most significantly the members of his Fishpond, continued and modified many of his reforms.

The Fishpond is mentioned in a large number of memoirs, biographies and historical studies. It is often perceived as a valuable resource that enabled Fisher to realize his organizational reforms, although derogatory appraisals are also prevalent. Fisher was often accused of favouritism and nepotism, and it has been argued that membership of or at least affiliation with the Fishpond was a prerequisite for an officer’s career success during the Fisher era. Although this might not have been entirely accurate, it has been pointed out that members of the Fishpond constituted a more talented batch of officers than those excluded from it. Fisher clearly wanted to handpick resourceful individuals to work on his reforms. However, the division between the progressives he embodied and the conservatives led by Beresford was by no means clear-cut. Many young pro-Fisher officers, such as Herbert Richmond, later became critical of the old admiral seeing, for instance, his preoccupation with materiel as an obstacle to true reform.

The aim in this article is to provide answers to the following research questions. What was the Fishpond in relation to the official structures and institutions of the RN? Who were the key and most influential officers in the Fishpond? How did their careers evolve in terms of carrying out Fisher’s central reforms? All in all, how effective was the Fishpond as a ‘tool’ in the process of reforming the RN, especially in the face of the fierce internal opposition to many of Fisher’s major reforms?

The article is based on the following groups of primary and secondary materials. The first group comprises unpublished and published primary materials. Thus, the unpublished and published professional and personal papers of admiral Fisher , the papers of Admirals of the Fleet John Jellicoe and David Beatty , both of whom acted as Commanders-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet and as First Sea Lords during the War or immediately thereafter, were consulted. What is more, the edited papers of Sir Maurice Hankey, the secretary of the Committee of Imperial Defence and of the War Cabinet , Hankey’s unpublished papers in the Churchill Archives at the University of Cambridge , the unpublished papers of Admiral of the Fleet Prince Louis of Battenberg, First Sea Lord 1912-1914 , and Winston S. Churchill’s papers on naval matters in the Churchill Archives at the University of Cambridge were consulted .

The second group of materials includes Fisher’s memoirs and biographies, and the extant memoirs and/or biographies of the key RN officers involved either in the Fishpond or in the upper echelons of the RN in general. Among the most important of these are the memoirs and biographies of Jellicoe , Beatty , Fisher’s greatest adversary Lord Charles Beresford , Admiral of the Fleet Sir Arthur Knyvet Wilson (First Sea Lord, 1910-1911) , Admiral Sir Francis Bridgeman (First Sea Lord, 1911-1912) , Admiral of the Fleet Prince Louis of Battenberg (First Sea Lord, 1912-1914) , Admiral of the Fleet Sir Henry Jackson (First Sea Lord, 1915-1916) , Admiral of the Fleet Sir Henry Oliver (Chief of Staff during the most of WWI) and Admiral Sir Percy Scott, the inventor of the Scott director firing system. The biography of Admiral Herbert Richmond, as well as the autobiography of Admiral Reginald Bacon were also consulted .

The third group comprises the key sources used to shed light on the organization and leadership of the RN during the Fisher era. It included studies on key admirals at the upper echelons of the RN organization , the organization of the British Admiralty and its initiative-suppressing culture , on the emergence of the naval staff after its belated inception in 1912 due to vehement opposition from First Sea Lords Fisher and Wilson , its strategy and war planning , and on Admiralty plans to counter the German threat.

The Admiralty Organization, Fisher’s Reforms and the Fishpond

In what follows, the central institutions of the British Admiralty are described in terms of the regulative, normative and cultural-cognitive elements that, together with associated activities and resources, provide stability and meaning in any given social setting. The formal organization of the RN and its rules, culture and norms, and the central beliefs related to the use of favouritism in the upper echelons of the organization are briefly discussed in line with institutional theory. The aim is to shed light on the context within which Fisher’s reforms took place and where he applied his own version of favouritism.

The British Admiralty was governed by the Board of Admiralty during the Fisher era of 1904-1919. The Board consisted of three political members (First Lord, Civil Lord, and Financial Secretary) and various professional members (the Sea Lords, the Permanent Secretary and some civilian professionals). After 1912, a Naval War Staff was formed under the leadership of the First Sea Lord and a separate Chief-of-Staff. It was renamed Naval Staff in 1917, and the First Sea Lord also assumed the role of the COS. Many supplementary committees (such as Fisher’s original Committee on Designs 1904-1907) supported the work of the formal institutions.

Within the British Admiralty, the First Sea Lord was the admiral who directed all strategic, tactical and organizational RN matters, assisted by three (later four) subordinate Sea Lords. The civilian First Lord was primarily a political figurehead who rarely interfered in professional matters: Winston S. Churchill, who served in 1911-1915, was an exception in this respect. The Second Sea Lord was responsible for the manning and training of the fleet, the Third Sea Lord and Controller for the provision of materiel, including ships and their armament, and the Fourth Sea Lord for supplies and transport (the Fifth Sea Lord was later responsible for the Naval Air Arm). As I will demonstrate below, most officers in the Fishpond centrally worked as Sea Lords at some point during their careers.

HMS Dreadnought (1906)

The positions of the Director of Naval Construction, the Engineer-in-Chief, the Director of Naval Ordnance, the Director of Dockyards and of Stores, and the Inspector of Dockyard Expense Accounts, which were under the governance of the Department of the Controller, were also central figures in the strategic leadership of the RN. The DNCs and DNOs were of tantamount importance to Fisher and his reforms. He worked with two eminent civilian DNCs: Sir Philip Watts (1902-1912, designing HMS Dreadnought and the Queen Elizabeth class of fast battleships, for example) and Sir Eustace Tennyson d’Eyncourt (1912-1924, designing the Renown class of battlecruisers and HMS Hood, for example). Fisher thanks both men heartily in his Memories. The Director of Naval Ordnance was another position very closely related to the duties of the Director of Naval Construction, responsible for everything related to guns, gun-mountings, magazines, torpedo apparatus, electrical fittings for guns and other electrical fittings. As I will show, many officers in the Fishpond essentially worked as DNOs and assistant DNOs in bringing about some of Fisher’s most important technological reforms and innovations.

In sum, Fisher’s post-1904 reform scheme entailed the scrapping of more than 150 obsolete men-of-war around the Empire, the creation of a Reserve Fleet with nucleus crews, the redistribution and concentration of RN fleets to home waters to counter the increasing German threat, and the introduction of many novel technologies into naval warfare, most significantly the Dreadnought battleship and the battlecruiser. Contrary to common assumptions, Fisher was, in fact, critical of battleships, and emphasized the importance of the torpedo and the submarine. Although many of his reforms proved controversial, and some appeared to have failed miserably, there is a consensus among historians that, in general, Fisher and his team was able to turn around the RN from its languid state before war broke out.

Robert L. Davison provides an analysis of the profound change in the officer corps of the RN during the period of 1880-1919. Most significantly, the rapidly developing naval technology and military professionalization created a need for fundamental change in the recruitment and education of officers in general, and engineer-officers in particular. The social and economic upheavals in Britain also meant that more officers were drawn from outside of the nobility and the upper classes. The leadership of the navy became a matter for public debate both in the media and in Parliament. All in all, there was an increasing emphasis on capability over social position and personal contacts in achieving promotion and success. This change was not easy, however, and the RN of the pre-Fisher era seemingly lacked the institutions and impartial procedures to ensure the promotion of the ablest individuals. What is more, the traditional culture of the RN emphasized the following of orders to the letter, and thus strongly suppressed subordinates’ own judgment and initiative. Fisher wanted to profoundly change the prevailing organizational culture of the RN, and especially the way in which officers were promoted to key positions.

Thus, the often-derided Fishpond essentially provided Fisher with the means to realize many of his hotly debated reforms. However, he still advanced the careers of its members by means of favouritism, not unlike the common practice in the 19th century, the difference being that those who were promoted were young, bright and personally loyal to their patron rather that men with family and social connections. Extant historical analyses have shown how civil servants, including RN officers, moved from the traditional patronage culture towards increased bureaucratization and professionalization in mid-19th century Britain. However, at the beginning of the 20th century the RN was still largely dominated by highly subjective officer-promotion methods that were heavily reliant on the opinion of superiors, especially in the case of candidates for the upper echelons of the organization. A positive perspective on favouritism is adopted in this article: it allows leaders to ensure the functioning of the organization in situations in which it is impossible to accurately and objectively monitor and incentivize subordinate behaviour and performance. This may apply, in particular, to the formation of well-functioning top-management teams for the visionary leadership of organizations. Favouritism may be a tacit-knowledge-based mechanism for ensuring that the right people occupy the right positions, especially in times of rapid and forceful change.

In general, Fisher was distrustful of the staff organization that was proposed for the RN at the beginning of the 20th century, a General Staff for the Army having been created in 1904. Although making some supporting gestures, he thought that a formal staff organization would constitute an intelligence hazard at the time of naval information leaks. What is more, he wanted to surround himself with trusted people he could choose himself, rather than relying on the establishment of a formal staff bureaucracy in the Prussian style. What he wanted was essentially a loosely-knit ‘brains trust’ instead of a formalized staff as the ‘brain of an army’ . The informal system that worked well for him for some time, however, quickly broke down under his successor, the autocratic and unapproachable Admiral Wilson. Consequently, a Naval War Staff was created in 1912 to formalize the analysis and planning at the Admiralty. Many Fishpond members contributed to the establishment and institutionalization of the staff organization, which were far from straightforward tasks.

The Fishpond comprised a wide-ranging collection of senior and junior officers both on land and at sea, including civil servants within the naval organization. Fisher also had a talent for recruiting ‘affiliate’ members into his personal network, who would be useful for his undertakings. As mentioned, these ranged from King Edward VII to key politicians, industrialists and representatives of the media. The focus in this article, however, is on the role of the relatively few high-ranking Fishpond officers in the upper echelons of the RN. All of them except for Bacon and Scott advanced to the highest naval rank of the Admiral of the Fleet.

The Fishpond: Key Personages, Careers and Roles

The following members of the Fishpond were the key affiliates Fisher primarily worked with before and during his first stint as First Sea Lord in 1904-1910. Many of them also held important positions at the Admiralty or afloat during the War and after it. They were, on average, 17 years younger than Fisher (Scott 12 years and Bacon 22 years). In what follows, the officers are portrayed in terms of their careers and major achievements, especially in the light of Fisher’s key reforms, focusing also on personality, leadership style and their relationship with Fisher.

Prince Louis of Battenberg

Perhaps the most influential Fishpond member before the War broke out, and an early and loyal follower of Fisher was Admiral of the Fleet Prince Louis Alexander of Battenberg (after 1917, 1st Marquess Mountbatten of Milford Haven, 1854-1921). A German prince of royal blood, albeit always also a British subject due to his close family relations with the British royal family (he was a grandson of Queen Victoria), Louis entered the RN at the age of fourteen in 1868. He quickly proved a resourceful and reliable officer with excellent social skills and connections, not least due to his high birth. Prince Louis was promoted to the rank of Captain at the relatively young age of 37 in 1891. In addition to captaining several men-of-war in diverse stations around the Empire, he acted as a liaison officer between the army and the navy, and as joint secretary of an organ that was later to develop into the Committee of Imperial Defence. He was appointed Assistant Director of the Naval Intelligence Division in 1899. What is more, he acted as an aide-de-camp to three monarchs: Victoria, Edward VII and George V.

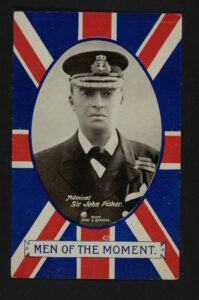

Fisher Postcard Image (Courtesy of the Author)

Prince Louis became more deeply acquainted with Fisher when he was acting as the captain of the battleship HMS Implacable in the Mediterranean Fleet, of which Fisher was the Commander-in-Chief. Fisher immediately recognized the wide-ranging abilities of the noble prince, which ranged from technical know-how to tactical and literary skills. Prince Louis was appointed Director of Naval Intelligence in 1902, and was promoted to Rear Admiral in July 1904, shortly before Fisher rose to power as the First Sea Lord in October. In his biography of Louis of Battenberg, Richard Hough argues that the prince essentially acted behind the scenes, using his connections in high society to get the controversial Fisher appointed as First Sea Lord in 1904. Fisher had previously made many enemies within the RN: as Second Sea Lord, for example, he instituted the controversial Selborne scheme, a novel concept for officer recruitment and training.

Prince Louis was given the command of the Second Cruiser Squadron in 1905, and in 1907 he took over as acting Vice Admiral and Second-in-Command of the Mediterranean Fleet. He was promoted to Vice Admiral and appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Atlantic Fleet in 1908. The size of the Fleet was considerably diminished following Fisher’s efforts to concentrate the most powerful ships in the North Sea to counter the increasing threat from the German Imperial Navy. Louis returned to the Admiralty as Second Sea Lord in December 2011, in charge of creating an Admiralty War Staff, which Fisher and Wilson had refused to do. He was promoted to Full Admiral in July 1912, and further appointed to succeed Admiral Sir Francis Bridgeman as First Sea Lord in December 1912. The young and dynamic First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston S. Churchill, endorsed Prince Louis’ appointment thinking that he would be less dogmatic than Fisher but more dynamic than either of his immediate predecessors Bridgeman and Wilson. What is more, with the malleable prince at the professional helm of the Senior Service, Churchill became the de facto strategist at the top of the Admiralty. First Lords thus far had rarely interfered in professional questions concerning ordnance and materiel, for example. Churchill, however, going against Fisher’s advice, decided in 1912 to drop battlecruiser construction altogether in favour of the fast battleships of the Queen Elizabeth class. On many occasions, however, the diplomatic Battenberg was able to moderate for instance the relationship between the First Lord and flag officers on the Admiralty Board. The latter were often exasperated by Churchill’s impulsive interferences in professional matters.

On the other hand, the organization of the war staff continued to possess serious structural flaws that were not modified until 1917. The key leaders at the top pondered the workings of the new naval war staff immediately before the war, but no structural changes were yet made. They thought it was up to the individuals in leading roles (such as the COS) to continuously develop better ways of working. A burning problem was that the Chief of the War Staff had no direct authority as he was not a Board member. What is more, the formal structure of the staff was over-centralized as everything had to pass through the COS, and many new staff officers were deemed unfit for their duties due to insufficient education in staff work. A Royal Navy Staff course at the War College was instituted in 1912 but proved slow to make progress in staff officer training.

According to Andrew Lambert, towards the end of his stint as First Sea Lord the apathetic and increasingly physically ill Prince Louis proved to be a disaster, especially in conjunction with the young and energetic but inexperienced Churchill. “No cabinet advised by Fisher would have made such a blundering, incompetent, disastrous response to the July Crisis.” The Germans clearly did not anticipate that Britain would follow its entente partners France and Russia into a continental war, even if the neutrality of Belgium were violated by the German Army. In line with his earlier intentions, and not least because of the strong anti-German sentiment among the British public and press, Churchill decided to discharge Prince Louis and to recall Fisher as First Sea Lord in late October 1914. Prince Louis felt immensely relieved following his dismissal. Before stepping down, he and the old Beresfordian and Admiralty Chief-of-Staff Vice Admiral Doveton Sturdee had made the fateful decision to send Rear Admiral Christopher Cradock’s obsolete cruisers to fight against the superior German East Asian Squadron commanded by Vice Admiral Maximilian Graf von Spee. This resulted in a humiliating British defeat at Coronel near the Chilean coast on the 1st of November, 1914. Prince Louis had no official position during the rest of the war, and in December 1918, First Sea Lord Admiral Sir Rosslyn Wemyss, another old anti-Fisher officer, strongly suggested he should retire, which he did on the 1st of January, 1919. Just a few weeks before his death in September 1921, he was promoted to Admiral of the Fleet on the Retired List.

Arthur Marder describes Prince Louis as “…a first-rate, all-round seaman, a born leader, an efficient, even brilliant tactician and strategist (he was not defeated in manouvres until 1912)”. However, as an administrator at the Admiralty he proved at least slightly less effective than as a seaman. The problems during his last months as First Sea Lord at the beginning of the War (the Goeben incident, the sinking of the three old Créssy class cruisers and the increasing submarine menace, as well as the crushing defeat at Coronel) easily overshadow his earlier successes such as building and organizing the entire Grand Fleet. In Fisher’s view, Prince Louis seemed occasionally to be so much under Churchill’s influence that he described the First Sea Lord as “Winston’s facile dupe”, which of course was a gross exaggeration. Although a Fisher loyalist, he demonstrated the ability to adapt his views in accordance with changing situations. He also detested the harsh way in which Fisher endorsed his views and suppressed criticism. As Prince Louis put it in a letter to a fellow officer as early as in 1905:

“…I do cordially agree with all you say, especially the fever which has seized hold of J.F. … also the senseless way in which he insults and alienates our senior men.”

Throughout the years, Mountbatten’s relationship with Fisher always remained relatively harmonious and mutually respectful. However, despite sincerity about professional matters, a certain formal tone and distance, absent e.g. from Fisher’s correspondence with his onetime First Lord and close friend Reginald McKenna, always persisted in their correspondence . Fisher was the master and Prince Louis the apprentice.

Sir John Jellicoe

Admiral of the Fleet John Rushworth Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe of Scapa (1859-1935) was Fisher’s self-evident favourite to command the Grand Fleet in the event of war.[1. “…I just mention all this to show what I’ve done for Jellicoe because I knew him to be a born Commander of a Fleet! Like poets. Fleet Admirals are born, not made! Nascitur nonfit!”; Fisher, Memoirs, 63; in a letter to Winston Churchill on the 30th of July 1913 Fisher strongly praised Jellicoe’s qualities as a potential wartime admiralissimo: “…the sacred fire of originality burns in him.”, CHAR 13/21/69; see also Fisher’s letter to Reginald McKenna in December 1911, in which he predicts a war with Germany in September 1914 and Jellicoe as Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleet (“So I sleep quiet in my bed!”), Marder (ed.) Fear God and Dread Nought, Vol. II, 419.] Jellicoe joined the RN in 1872 and fought as a young officer in the Anglo-Egyptian War of 1882. Promoted to Captain in January 1897, he immediately became a member of the Ordnance Committee of the Admiralty. During the Boxer Rebellion in China, he was seriously wounded in the Battle of Beicang on the 5th of August 1900. As a recognized ordnance specialist, Captain Jellicoe became Naval Assistant to the Third Naval Lord and Controller in 1902.

Fisher made Sir John Jellicoe, one of his famous ‘seven brains’ , the Director of Naval Ordnance in 1905, Second-in-Command of the Atlantic Fleet in August 1907, Third Sea Lord and Controller of the Navy in October 1908, and Commander-in-Chief, Atlantic Fleet in December 1910. In fact, Jellicoe succeeded Prince Louis in many of these key appointments.

After Fisher’s retirement in January 1910, Jellicoe was appointed Second-in-Command of the Home Fleet in December 1911 and, having also been appointed Commander of the 2nd Battle Squadron in May 1912, became Second Sea Lord in December 1912. He was promoted to Rear Admiral in 1907 and to Vice Admiral in 1911, consequently .

At the outbreak of the Great War, as Fisher had originally planned, Jellicoe was immediately assigned to the command of the renamed Grand Fleet, replacing the aging Admiral George Callaghan. In the same process, he was promoted to Full Admiral on the 4th of August 1914. He commanded the Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutland in 1916, where his cautionary actions and failure to annihilate the German High Seas Fleet were later seriously criticized by the pro-Beatty faction. On the other hand, as Churchill’s famous adage goes, Jellicoe was after all “the only man who could lose the war in one afternoon”, and he obviously did not want to jeopardize the material supremacy of the RN with daring moves in any battle. What is more, he deployed his vast fleet in an exemplary manner at the height of the battle and crossed his German opponent Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer’s T twice. Jellicoe was appointed First Sea Lord in November 1916 but was forced to step down from the post already in December 1917, partly because he refused to dismiss his fellow Fishpond member Bacon from the command of the Dover Patrol. Jellicoe was promoted to Admiral of the Fleet in April 1919. After the War, he served as the Governor-General of New Zealand.

Sir John Jellicoe’s character is often described as calm, rational and unassuming. He was seemingly highly appreciated by his officers and on the lower deck. On the other hand, he was unable to delegate and often buried himself in work that could have been readily taken care of by his staff. According to Arthur Marder, Jellicoe possessed all the ‘three aces’ of an excellent admiral: a gift for leadership, a fertile imagination and a creative brain, as well as an eagerness to make full use of the ideas of his junior staff. Nevertheless, he may have been somewhat wanting in the ‘fourth ace’, an offensive spirit. What is more, he was a product of the traditional RN culture that downplayed subordinates’ initiatives. Unlike Fisher, he preferred to craft very detailed strategies and battle orders. The modest and sensible Jellicoe worked extremely well with the rule-flaunting and impulsive Fisher, who was normally not interested in technological details among other intricacies. For instance, as a key member of the Committee on Designs in 1904-1907, he took a leading role in the development of the new dreadnought battleships and battlecruisers. After a tiresome stint as the C-in-C of the Grand Fleet he was not entirely successful during his term as First Sea Lord. He became increasingly prone to pessimism, and could have done more, such as introducing the convoy system that eventually countered the German submarine menace in 1917.

All in all, Jellicoe was one of the most talented and influential officers in the Fishpond, a personality who could, when necessary, present even Fisher with cold facts and effective counterarguments. This is clearly evident from their abundant correspondence, in which both gentlemen most frankly discussed presently topical naval themes . Fisher appreciated this greatly. During the war, however, their relationship started to deteriorate as Fisher was prone to offer his strong (mostly unsolicited) views on a plethora of naval and other subjects to Jellicoe. For instance, when Fisher in January 1917 offered the newly-appointed First Sea Lord Jellicoe his services as Third Sea Lord and Controller, he felt wounded by the prompt negative reply from his old friend and former subordinate. Donald M. Schurman states about Jellicoe that “…In many ways he was remarkable and successful, and certainly he has been the most generally undervalued of the entente leaders during World War.”

Sir Henry Jackson

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Henry Bradwardine Jackson (1855-1929) was a member of Fisher’s seven brains and thus a key officer in the ‘original’ Fishpond. He joined the RN in 1868 and served as a young officer in the Anglo-Zulu war in 1879. A specialist in wireless communications, he became Assistant Director of Naval Ordnance in 1902, Captain of the battleship HMS Duncan in 1903, and Captain of the torpedo-school ship HMS Vernon in 1904.

Fisher had Jackson appointed to the post of the Third Sea Lord and Controller in 1905. Jackson was promoted to Rear Admiral in October 1906. Following a cruiser command in the Mediterranean in 1908-1911 he was promoted to Vice Admiral on his appointment as Director of the Royal Naval War College, which Fisher had established in 1907 to substitute the absent Naval War Staff (albeit a War Course College had existed since 1900). Having been appointed Chief of the new Admiralty War Staff in 1913, Jackson became a Full Admiral in February 1914.

To the surprise of a great many observers, Jackson was appointed Fisher’s successor as the First Sea Lord after the latter’s spectacular resignation in May 1915. Although he worked well with the new First Lord, former Prime Minister Arthur Balfour, who had replaced Winston Churchill at approximately the same time, most historians tend to characterize the Balfour-Jackson administration at the Admiralty as lethargic and void of initiative. Most importantly, the rate at which capital ships were fitted with director firing slowed down, and the completion dates of the great number of ships that Fisher had ordered were pushed into the future. Jackson was replaced by Jellicoe as First Sea Lord in December 1916. He acted as the President of the Royal Naval College during the rest of the war and was promoted to Admiral of the Fleet in July 1919.

Jackson was profoundly professional (an ‘electrician & engineer’ ) but in terms of personality he has been characterized as colourless and lacking in imagination. As Arthur Marder points out, he was lacking in all the ‘three aces’ of an admiral: leadership capability, a fertile imagination (except perhaps in technical matters), and the ability to use the brains of juniors. Early on, Fisher succeeded in capitalizing on Jackson’s technical skills, especially in developing inter-ship communications for Empire-wide duty. As the second COS of the Admiralty War Staff, Jackson also played a central role in gradually building up a proper staff organization in the RN. Despite the fact that Fisher did not hold Jackson in high regard as an administrator, the relationship between the two admirals was uncomplicated until Jackson surprisingly became Fisher’s successor as First Sea Lord. Fisher vehemently criticised the Jackson-Balfour administration for a serious lack of initiative and imagination.

Sir Reginald Bacon

Admiral Sir Reginald Hugh Spencer Bacon (1863-1947) was an officer especially noted for his technical and literary abilities. With Prince Louis and Jellicoe, Bacon was probably among the men who were closest to Fisher in the entire Fishpond, and he wrote the biographies of both Fisher and Jellicoe after the War. Among Fisher’s original ‘seven brains’, he had a significant effect on various reforms in the RN, especially on matters to do with materiél and ordnance.

Bacon entered the RN in 1877 and specialized in torpedo craft. He met Fisher while serving as a Commander in Fisher’s Mediterranean Fleet in 1899. C-in-C Fisher was impressed by the technical abilities of the young officer. Following Bacon’s promotion to Captain in 1900, Fisher strongly influenced his appointment to the novel post of Inspecting Captain of Submarines (ICS). In that capacity he was to have a significant influence on the development of the submarine branch of the RN, in accordance with Fisher’s emerging views that the Home Isles should be defended mainly with light vessels and that fast and powerful battlecruisers should be built to patrol the Empire’s lanes of communication on the high seas. Bacon was appointed the first captain of Fisher’s revolutionary all-big-gun battleship HMS Dreadnought in June 1906, and in 1907 he was appointed to the central position of the Director of Naval Ordnance to succeed Jellicoe. He was promoted to Rear Admiral in 1909. However, following the fall of Fisher in late 1909 he decided to retire, and took up the well-paid position of managing director at the private Coventry Ordnance Works. On the outbreak of the war he returned to active service and in 1915 was appointed to the command of the Dover Patrol. He was promoted to Vice Admiral in July 1915. After a controversy over his management of the Dover Barrage against German submarines, the newly appointed First Sea Lord Rosslyn Wemyss had him ousted, and Roger Keyes replaced him in January 1918. Again, a Fishpond member was dismissed by the anti-Fisher Wemyss. Bacon was promoted to Full Admiral in September 1918.

As a personality, Bacon has been described as brilliant but arrogant, slow to acknowledge his mistakes, and an authoritarian leader who did not get along well with his men. What is more, unlike his patron Fisher who was keen on delegating authority where he saw talent, he was more of a centralizer, and later in his career he developed an excessively risk-avoiding attitude.

In his often-avant-garde views of how naval warfare should develop in the future given the rapid development in the use of torpedoes, mines and the submarine, especially against large capital ships, Bacon offered considerable professional support to Fisher, who was not an expert in technological details. He remained personally loyal to the old admiral throughout his career, which is evidenced in the polite tone of the 1929 Fisher biography he authored. However, outside the realm of technology and ordnance, he had a limited effect on the reorganization of the RN in general. This may have been due to the limitations of his personality and leadership skills, especially his inability to mobilize and motivate his followers.

Sir Percy Scott

Admiral Sir Percy Moreton Scott, 1st Baronet (1853- 1924) was an inventor and a pioneer in naval gunnery, best known for his director firing system. He joined the RN in 1866 and, like Fisher, was present at the 1882 British naval bombardment of Egyptian forts at Alexandria. He witnessed the inaccuracy of the British gunners and started devising his own plans to improve gunnery practices in the RN. He started this work at HMS Excellent, the gunnery school, captained by Fisher. Fisher always believed strongly in Scott’s innovative capabilities. Promoted to Captain in 1893, Scott served on the Navy’s Ordnance Committee until 1896 when he was given his first sea command, HMS Scylla, a cruiser in the Mediterranean Fleet. He was now free to implement his ideas on improved gunnery, scoring an unprecedented success during the 1897 gunnery trials. He took part in suppressing the Boxer Rebellion in China, and the then Second Sea Lord Fisher had him appointed Captain of HMS Excellent in 1903. Scott developed his gunnery theories further, reaching the flag rank in 1905. Fisher tailored him the position of Inspector of Target Practice, which he held in 1905-1907.

In 1907 Scott took command of the 1st Cruiser squadron of the Channel Fleet under the command of Lord Charles Beresford. Not an easy subordinate, he famously quarrelled with Beresford on two occasions. No doubt these incidents were also linked to the ongoing Fisher-Beresford feud, and the latter wanted to discipline Scott, a prominent Fishpond member. Fisher came to his rescue, and Scott was never court-martialled. After a sea command and promotion to Vice Admiral in 1908, Scott returned in 1909 to develop his promising director firing system. He notes in his autobiography that there was significant Admiralty opposition to his new system, which promised remarkably improved target-practice results. Resistance to change and new technology are probably the main reasons why a large number of RN officers resisted Scott’s innovations (as they also did in the case of Pollen’s superior fire-control equipment). Scott attributed the resistance to ‘professional jealousy’. He was promoted to Full Admiral and created a baronet upon his retirement in 1913.

Only eight dreadnoughts had been fitted with Scott’s director firing system at the outbreak of war. Meanwhile, Scott returned from retirement to work on improving fire control and countering the German submarine menace. Like Fisher, he was convinced that the era of the battleship would soon be over due to the increasing threat from ever-more advanced submarines, mines and aerial attacks.

As a person, Scott was extremely outspoken and often hard to work with. According to Peter Padfield: “But if Scott acted like a bone stuck halfway down the throat of anyone senior to him, he was very much on the side of the subordinates who measured up to his standards – and they for him.” Fisher and his key disciples Prince Louis and Jellicoe appreciated Scott’s talents very much, and realized the importance of his director firing system for the gunnery of the RN. However, Fisher fully realized that Scott was not the easiest person to work with and a lot of problems originated from the gunnery expert’s ways of dealing with superiors. In the end, the road to improved fire control generally proved long and winding. Peter Padfield goes as far as stating: “… the three great men of this pre-war navy, Fisher, Scott, Jellicoe, who lifted the Service bodily between them to unequalled heights of material and technical efficiency and training. Others helped, many vitally, but these were the three men.”

Sir Charles Madden

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Charles Edward Madden, 1st Baronet (1862-1935) was also a member of Fisher’s original seven brains. His marriage to the sister of Jellicoe’s wife further strengthened his connections to the inner circle of the Fishpond. Having joined the RN in 1875, he was involved in the Anglo-Egyptian war in 1882. A torpedo officer by training, he was promoted to Captain in 1901 and posted to the Mediterranean Fleet, where he became acquainted with Fisher. He joined Fisher’s Committee on Designs in 1904 and was appointed Naval Assistant to Third Sea Lord Henry Jackson in February 1905. Madden went back to sea in 1907 as the Captain of HMS Dreadnought and Chief of Staff to Sir Francis Bridgeman, C-in-C of the Home Fleet. In December 1908, he was appointed Private Naval Secretary to Reginald McKenna, First Lord of the Admiralty and Fisher’s closest ally. Upon Fisher’s resignation in January 1910 he was given the post of Fourth Sea Lord, responsible for RN supplies. Promoted to Rear Admiral in 1911, he was given Home Fleet and cruiser-squadron commands until war broke out. When Jellicoe was appointed C-in-C of the Grand Fleet he asked that his brother-in-law be appointed as his Chief of Staff. He was posted to the Grand Fleet in August 1914 and promoted to acting Vice Admiral in 1915. For his services at the Battle of Jutland he was promoted to Vice Admiral in June 1916 and was further promoted to Second-in-Command of the entire Grand Fleet in December 1916. He became a Full Admiral in February 1919, and Admiral of the Fleet in 1924.

Madden was a gentlemanly leader, and an esteemed professional who worked well with Fisher and the key members of the inner circle of the Fishpond. Arthur Marder describes him as “…a simple, reserved, very sound and knowledgeable officer, pre-eminent as a tactician, and somewhat lacking only in imagination”. As a slightly younger member, he was initially overshadowed by his brother-in-law Jellicoe, as well as the by Admirals Prince Louis and Henry Jackson. Unlike Bacon, however, and with his excellent social and leadership skills, Madden later advanced to key positions in the upper echelons of the RN (he was First Sea Lord in 1927-1930, for instance). Madden’s correspondence with Fisher is rather formal, strict to the point and extremely polite in tone, suggesting less personal familiarity .

Sir Henry Oliver

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Henry Francis Oliver (1865-1965) was a Royal Navy officer and a Chief of Staff during the Great War. He joined the navy in 1877 and was originally trained as a navigating officer. He became the first captain of the new navigation school HMS Mercury in 1903 and was appointed Naval Assistant to First Sea Lord Fisher in 1908. He also served Fisher’s successors in that capacity until 1912. Promoted to Rear Admiral in 1913, he became Director of the Intelligence Division at the Admiralty. After the outbreak of the war he was appointed Naval Secretary to First Lord Churchill, and Chief of the Admiralty War Staff in November 1914. When Jellicoe was appointed First Sea Lord and also assumed the position of COS in December 1916, Oliver became Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff. Oliver’s his role in directing the Battle of Jutland from the Admiralty has been debated. He served as Commander of the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron in the Grand Fleet during the last year of the war. Promoted to Vice Admiral in 1919, he became Commander of the 2nd Battle Squadron, Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleet and, finally, Commander-in-Chief of the Reserve Fleet. Consequently, he became Second Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Personnel. He was promoted to Full Admiral in 1923, and to Admiral of the Fleet in 1928. He retired in 1933.

Among Fisher’s key assistants (other former assistants to Fisher who did not rise to the highest naval rank were Captain Thomas Crease and Admiral Charles de Bartolomé), Oliver was ‘a hard worker and full of common sense’. As COS and DCNS he was a ruthless centralizer, unable to delegate and prone to micromanagement. In this, he greatly resembled Jellicoe. With his deep knowledge following his long tenure directing the staff, Oliver tended not to trust his subordinates’ opinions. All in all, William James refers to Oliver as probably one of the greatest architects of the new navy, even surpassing Fisher. As COS and DCNS he built up the organization and working practices of the expanding naval staff during the War. However, C.I. Hamilton argues that both Oliver and Jellicoe had a severely distorted view of staff duties, regarding them mainly as clerical and administrative in nature. This is exactly why Fisher was so opposed to the building of a large bureaucratic staff in the first place: what he wanted was a loosely coupled body that would be able to focus more strongly on the creation of a strategic vision and its efficient implementation. A new and more decentralized organizational and staff structure was implemented once both Jellicoe and Oliver had left the Admiralty.

Conclusion

As is obvious from the above description of the careers and roles of the most important high-ranking officers in the Fishpond, it consisted of a loose network of diverse personalities with different talents. The mere existence of a unified Fishpond systematically machinated by Fisher can be strongly questioned in the light of historical evidence. For the most part, the Fishpond was a derisive concept used by Fisher’s opponents in the public campaign against his person and his organizational designs. However, it is true that Fisher intentionally surrounded himself with a cabal of suitable men he thought could be useful to him in realizing his ambitious plans. Fisher clearly believed that these key individuals, with the support of the informal advisory service provided by the War College at Greenwich, would suffice to run the navy without a formal staff. Most of the prominent Fishpond members, especially Prince Louis, were nevertheless opposed to this view and strongly advocated the creation of a staff organization, which happened in 1912. Gradually, the more and more professional staff organization took over and formalized many strategic functions that the informal network of Fisherites had performed earlier.

As far as the careers and roles of the members of the Fishpond were concerned, Fisher obviously secured central positions and promotions for the men he trusted the most. However, he did not have a grand master plan in terms of who was needed, where and why: He was merely using his instincts and gut feelings in deciding whom to appoint to what position and whom to sack. When he was in power, he usually got his way. Even when out of power, he bombarded his associates (especially Churchill and Jellicoe) with copious plans how to fill the most important top positions of the RN on land and at sea. He was also ingenious in using committees and informal teams of experts to develop individual parts of his reform scheme. In this respect, especially as a military leader, he was ahead of his time as a delegator and de-centralizer. The above analysis of the role of the key members of the Fishpond gives strong evidence of their major and often decisive contributions to Fisher’s and his successor First Sea Lords’ reforms in the RN organization. They also adapted and further developed – and sometimes abandoned – many parts of the original reform scheme, especially during the War. In many ways, the key officers originally hand-picked by Fisher evolved over and above (and sometimes below) the roles that their patron had envisaged for them.

It is no surprise that as Radical Jack aged, reluctantly gravitated away from the centre of power in the RN and saw many of his original plans come to nothing, he uttered many bitter words about his former disciples, especially Jellicoe. After his resignation in 1915, he often wrote about his desire to return to the Admiralty, even to positions more minor than the one of the First Sea Lord. Many Fisherites also noted a gradual decline in his mental and physical capabilities. Admiral Bacon wrote in his autobiography, for instance, that the great tragedy of Fisher’s life was that he did not die in December 1914 after Coronel had been avenged at the Falklands. Had he done so he would have retained a reputation second only to that of Nelson.

Fisher could be very burdensome to people at the higher echelons of the RN, especially during the last years of the War. As the chairman of the Board of Invention and Research, he used certain organs of the Press to comment vehemently on the alleged incompetence in conducting the naval war, trying to further his aim of being recalled to the Admiralty. Jackson (then First Sea Lord), for instance, had told Hamilton (Second Sea Lord) in March 1916 that he could only attend to the war in the intervals between answering Fisher’s questions. As his former favourite, Jellicoe received most of the literary bombardment from the old admiral.

Three general conclusions about leadership in general can be drawn from this study of the Fishpond, which reflect issues that have changed little since the days of the Royal Navy of the Fisher era. First, top leaders are essentially team builders, able to find, motivate, develop and keep talent that they think best suits their organization. Fisher was at his best building a loyal coterie of bright and talented followers, especially at the height of the reforms during his first stint as First Sea Lord. Visionary leaders, a rare species especially in the setting of a military organization, inspire talent to flock to their cause. No other First Sea Lord (except perhaps for Beatty later on) was as capable of enthusing followership as Fisher was. It is also interesting that Fisher’s most loyal and effective followers were approximately 10-20 years younger than he was (junior officers had always been fond of Fisher’s unconventional approach, and he liked to directly hear their opinions about necessary improvements in a great number of matters). Followership thus seems to have something to do with age difference. Followers may need to be younger than the patron to remain respectful, but if they are considerably younger, the mind-sets, world views and ways of working are not necessarily compatible any longer. The patron simply becomes too old to imbue followership.

Second, leading is about the coupling of the formal and the informal organization, often bypassing the bureaucracy created by the former. Even in a military organization, no leader can have ‘absolute rule’, and even the most autocratic leaders need an informal network of people in key positions to back them up. Fisher’s favouritism was obviously an attempt to establish such a network when the extant regulative institutions of the RN proved inept at providing the First Sea Lord with officers of sufficiently high intellectual calibre. Fisher’s leadership was essentially about using the informal organization to achieve his desired organizational goals. Third, effective leadership styles vary across individuals, organizations and along leader careers. Even the mightiest leaders may occasionally be inconsistent and may panic or become pessimistic under pressure. They should be at the right stage of their career path to effectively function in a certain leadership position. The longer the tenure in one leadership position, the more likely are the outcomes to deteriorate at some point. These aspects are easily observable in Fisher’s own leadership as he aged. His first stint as First Sea Lord was considerably more successful than his second one during the War. Similar developments can be detected in the careers of his Fishpond members, too. At least Prince Louis, Jellicoe and Bacon served in positions to which they were no longer necessarily the best options. Prince Louis’ tenure as First Sea Lord lasted perhaps too long, Jellicoe should never have accepted that position at the first place and Dover Patrol proved to be too demanding a command for the increasingly cautious Bacon. Thus, the effectiveness of a leader in a certain position tends to follow an inverted U-shaped curve. What is more, different leader characteristics and leadership styles tend to complement each other in organizational change. The careers of all admirals described above are a good illustration of this. Fisher’s visionary broad brush often needed Jellicoe’s calm rationality and Scott’s deep expertise.

(Return to December 2022 Table of Contents)

Footnotes