Contents:

Introduction

The Declaration of Paris and the “Barbarous Warfare” of Privateering

The Righteous Victim: Spain’s Contradictory Diplomacy over Privateering

Professionals and Privateers: American Naval Strategy in the War with Spain

Honor for want of a Ship: Spanish Naval Strategy in 1898

Conclusion

Bibliography

Scott D. Wagner

Undergraduate Student

College of Wooster

Introduction

The front page of the New York Times for April 25, 1898, ran the headline that dominated newspapers around the world that day: The United States had declared war on Spain. The second largest headline on that page? “Spain to Use Privateers.”

Privateering, the practice of private individuals with government authorization seizing enemy commercial property at sea, was nominally abolished with the Declaration of Paris in 1856. However, neither the United States nor Spain signed on to the Declaration. As tensions rose between the two states in early 1898, European observers grew concerned that one or both of the sides would outfit privateers in the fast-approaching war, wreaking havoc on international commercial networks and violating the rights of neutral merchant vessels. Coastal communities in the United States, too, were concerned over the threat that Spanish privateers could pose to their commercial activities and their safety.

Neither side officially announced their intentions on privateering until war broke out in April. The same day that President McKinley announced the blockade of Cuba, Secretary of State John Sherman sent a note to foreign powers pronouncing the United States’ decision not to use privateers. President McKinley announced the decision to the public three days later, on April 25. In the royal decree proclaiming a state of war issued on April 23, Queen Regent of Spain Maria Cristina stated that Spain would reserve the right to commission privateers but would not issue letters of marque until circumstances deemed it necessary. Circumstances apparently never deemed it necessary; Spain never sent out privateers during the war to attack American commerce or protect their own merchant vessels.

This essay seeks to examine factors that contributed to privateering’s absence in the Spanish-American War. The reasons were not technological; the Americans used private ships and private crews during the conflict, demonstrating that citizens with little to no sailing experience could adequately man modern ships of steam and steel. To fully investigate the lack of privateering, a broader approach is needed, one that takes into account the strategic and diplomatic concerns of each belligerent. Through such an extensive approach it becomes clear that the practice of privateering never fit in with the military and diplomatic strategies at play in the Spanish-American War.

The Technological Argument: Privateering and Modern Warships?

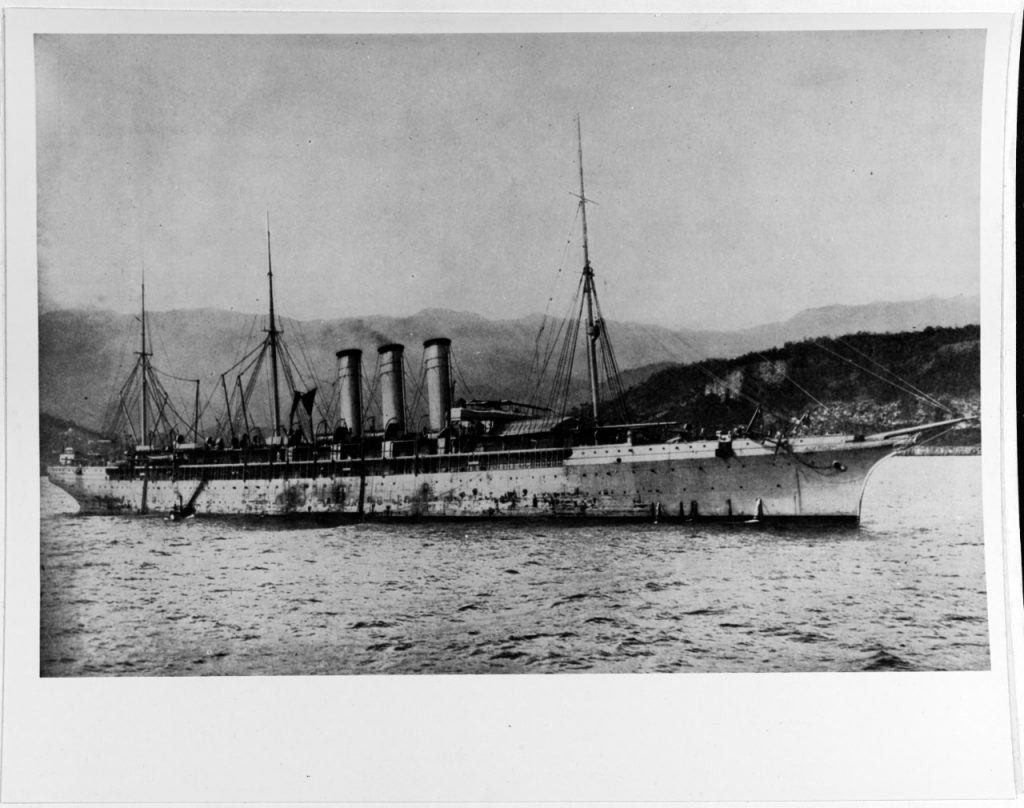

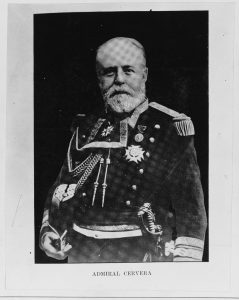

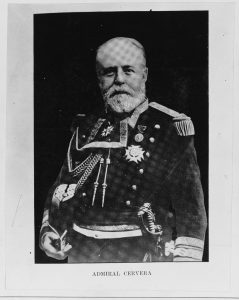

In a letter written to Spanish Minister of Marine Segismundo Bermejo in March 1898, Admiral Pascual Cervera described at length his ideas for Spanish naval strategy in the upcoming war with the United States. He was not optimistic about Spain’s chances at all, believing the main fleet under his command should stay in European waters rather than sailing to the West Indies. He was even less optimistic about the prospect of privateering:

I do not speak on the subject of privateering, because it seems to me that no man acquainted with history can attach any value to privateering enterprises, which nowadays are almost impossible on account of the character of modern vessels.

In short, Cervera believed that private citizens could not crew modern vessels. To his credit the last time privateers had sailed during a major war was in the American Civil War, when many of the ships still had wooden hulls. Crews now had to deal with the complexities of steam engines and recoaling ships, something not seen on privateer cruises in the age of sail. However events from the Spanish-American War show that Cervera’s argument that privateering was not technologically feasible does not hold water. During the war the US Navy frequently used private citizens to crew private vessels, a practice that appeared so similar to privateering that Spanish observer and artillery captain Severo Gómez Núñez stated that “There can be no doubt as to this system being privateering, and it was practiced as often as there was a chance.”

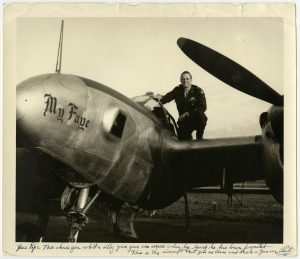

The Yale, Captain W.C. Wise, was one of the auxiliary ships loaned to the US Navy by the International Navigation Company for the duration of the war with Spain. (Naval History and Heritage Command photo NH 85345)

Shortly before and during the war, the American Navy Department purchased or received on loan a number of private ships from the merchant marine and independent contractors to create an auxiliary navy. Of the auxiliary navy four ships are of particular note: the

St. Louis,

St. Paul,

Harvard, and

Yale, known collectively as the American Line ships. These vessels were transatlantic steamers of the International Navigation Company that in peacetime sailed the route from New York to Southampton. The

Harvard was originally the

New York, and the

Yale originally the

Paris; their names were changed for the duration of their time in the US Navy. Each ship could do twenty-one knots, making them faster than many of the auxiliary cruisers and nearly every capital ship in the American navy. The

Harvard (Captain Cotton) and the

Yale (Captain Wise) had a 13,000-ton displacement, while the

St. Louis (Captain Goodrich) and the

St. Paul (Captain Sigsbee, former captain of the

Maine) displaced 14,910 tons. The ships were captained by US Navy officers, but were not crewed by navy seamen; rather, they were manned by their regular, private crews. In a lecture given after the conflict at the Naval War College, Captain Goodrich explained the reasoning behind the decision. The ships of the US Navy were already undermanned by the start of the war, “obliging [the navy]… to call largely for volunteers to supply the deficiencies.” Rather than using the untrained civilians of the Naval Militia to man the ships, why not use the regular crew that had the best knowledge of the intricacies of each vessel and its machinery? The American Line ships were privately-owned, privately-manned ships (excepting their captains) that were ideally suited to pursuing and capturing enemy merchant vessels.

Owing to their high speed and mobility the American Line ships were used in a variety of capacities during the war. When the conflict began the Harvard, Yale, and St. Louis were dispatched to the Caribbean; the St. Paul had not yet completed its armament, and remained at Hampton Roads for the time with Rear-Admiral Winfield Schley’s squadron. After the Americans blockaded Cuba, the American Line ships were tasked with locating Cervera’s fleet. The Harvard monitored the area around Martinique, the St. Louis, Guadeloupe, and the Yale, Puerto Rico in an attempt to spot Cervera as he entered the Caribbean. The Harvard found the Spanish first; on May 11 Captain Cotton telegraphed to Washington the presence of five Spanish ships just off the coast of Martinique. Cervera sailed to Curaçao for coal then proceeded to Santiago de Cuba. Once there, he was blockaded by a fleet of American ships including the St. Paul, the Harvard, and the Yale. Meanwhile the St. Louis busied itself with another task: cable-cutting. The auxiliary ship under Goodrich succeeded in cutting off Spanish communications to Guantanamo and Haiti, and drove off the Spanish gunboat Sandoval while doing so.

With Cervera trapped in Santiago, the Americans could safely deploy the Army for a landing in Cuba. The American Line ships helped in this process too, serving as troop transports for Major General William Shafter’s army. Captain Goodrich was glowing in his praise for the St. Louis during the deployment:

For four days and nights she acted as mother-ship, feeding and berthing nearly 200 extra men and officers; coaling, watering, and repairing steam cutters; furnishing voluntary relief crews of machinists and firemen for the latter for night work…and all this without even taxing her facilities.

Though they did not play a major role in the Naval Battle of Santiago, the American Line ships did help rescue prisoners from the destroyed Spanish vessels, particularly the Infanta Maria Teresa and the Oquendo. The Navy Department then used the American Line ships to transport the Spanish prisoners northward and back to the states. During their time in the Caribbean the auxiliary cruisers captured multiple Spanish vessels, for which the officers and private crews of the ships received compensation in the form of prize money – the Navy Department did not eradicate prize money until shortly after the war. After the ceasefire and the ensuing peace treaty, the four ships were returned to the International Navigation Company.

In his postwar lecture Goodrich summed up the exemplary service of his ship, St. Louis:

I am informed by the port captain of the American Line that of the four big liners, the St. Louis, the only one which did not adopt navy enlistments, and routine, made more miles, did more work and more kinds of work, cost less in operation and returned in better order than any of her sisters…The record of the ship is notable. She spent six weeks at sea without taking on board a ton of coal, a gallon of water or a pound of provisions, during which period she scouted, captured blockade runners, landed Shafter’s army, housed and fed at one time as many as two hundred sailors detached from the fleet for this landing service, cut cables, and brought seven hundred of Cervera’s men north as prisoners.

Bear in mind that the American Line ships that took part in all the operations Goodrich describes were private vessels with private crews, albeit under naval command. The crews of these ships even took prize money during the war, making their service eerily similar to the practice of privateering. While there are clear differences between the functioning of the American Line ships and the actions of privateers, it is clear that the privately-owned, privately-operated auxiliary steamers provided exemplary service in a variety of capacities during the Spanish-American War.

The American Line ships proved an effective fighting force, even with private crews. The vessels had enough force and firepower to capture enemy merchant ships and lightly-armed craft, and had enough speed to avoid confrontation with a larger ship or fleet. Private ships could still be used in war in the late 1890s; but could private citizens – the likes of which would make up the bulk of privateer crews – effectively man modern vessels? The crew of the American Line ships were exemplary, but they were also trained seamen familiar with the machinery on board the vessel, something unlikely to be found on an average privateer. To analyze the effectiveness of private citizens manning armed vessels in wartime, we can turn to the Naval Militia.

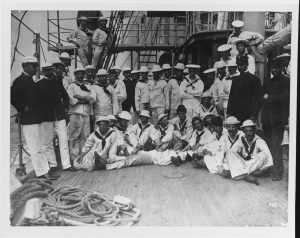

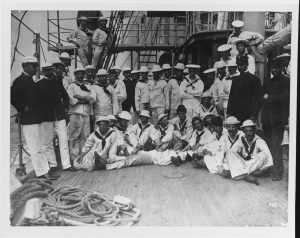

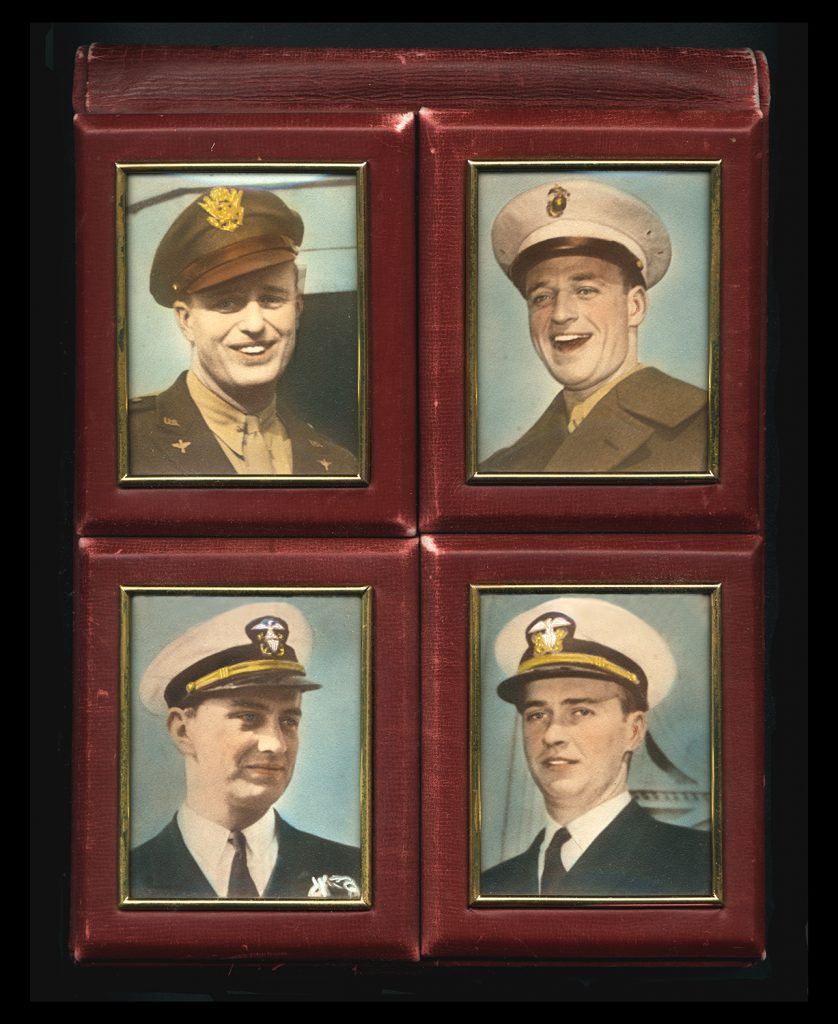

Many private citizens served in various Naval Militias during the war with Spain, often serving with auxiliary cruisers and coastal monitors. (Photo by James H. Hare; Naval History and Heritage Command photo NH 96734)

The Naval Militia was used by the Navy Department to augment undermanned crews of auxiliary ships. Made up of generally well-educated professionals from seaside states, the Naval Militia served with auxiliary cruisers and in other units established by the US Navy for coastal defense. In some cases, such as on board the Yankee and the Yosemite, the entire crew (excepting the captain and navigation officers) was comprised of men of the Naval Militia. Almost every report regarding the Naval Militia refers to the ardent motivation of the volunteers during the war. Commander Willard Brownson appreciated the “zeal and intelligence” possessed by the men under his command. Commander Charles Train, captain of the Prairie, admired his men’s “patriotism, zeal and intelligence.” Chief of the Bureau of Navigation Arendt Crowninshield, in a letter to Secretary Long, noted that the Naval Militia as a whole were “zealous and attentive” in their duties.

While no one could argue against the enthusiasm displayed by the Naval Militia, some captains were skeptical of their effectiveness. A report in the Army and Navy Journal cited officers that believed a crew of Naval Militia “would do more thinking than fighting.” Crowninshield believed that they “lacked all of the training and sea experience which would have made them really efficient.” Lieutenant Lazarus Reamey was especially critical of the Maine Naval Militia, stating that “not a single one of the number has the slightest appreciation of the qualifications necessary for service on board a government vessel.” Commander William Emory had the most reason to discredit the Naval Militia; in his ship Yosemite he threw 28 men in the brig for supposed drunkenness, though some militiamen claimed Emory was an incompetent officer. The men of the Naval Militia were not professional seamen, and some opponents of the organization were critical of its perceived improper attitude and performance during the war.

There were also a number of officers who were supportive of the Naval Militia. Commander Train believed the “industry and subordination” of the militia under his command were “beyond praise,” and described how,

The hard labor of coaling, the constant drills, and in short the complete change in their conditions of life from those to which they had been accustomed have been borne by them most willingly and cheerfully, and that, too, in spite of the fact that the ship, for the greater part of her cruise, was performing duty of a sort and in places that furnished no chance of an occasional attack of an enemy to break the monotony and furnish the excitement which alone can make such a life endurable.

Secretary Long’s report for the year 1898 admitted that while the Naval Militia lacked experience, they “rapidly acquired while on shipboard the knowledge necessary for their efficiency.” Long was supportive enough of the Naval Militia to claim “that the country has been amply repaid” for the cost of training the volunteers. The report of the assistant secretary supported Long’s praise, stating that the Naval Militia “served with great intelligence and enthusiasm” and that they “made good men-of-warsmen.”

The performance of the Naval Militia was mixed. They were enthusiastic and happy to serve, but at times apparently lacked the necessary maritime knowledge to provide the most efficient service. Some of the complaints against the Naval Militia were not against their effectiveness but their professionalism. Commander Willard Brownson, captain of the Yankee, stated that “in caring for their messes, their bags and hammocks, scrubbing their clothes, and in many of the minor details of a man of war, [the Naval Militia] were almost entirely ignorant.” However, Brownson also states that “in performing the ship’s duties they were willing, and after some weeks, became fairly efficient.”

So how can we evaluate the performance of the Naval Militia, and could the members of the various Militias have provided adequate service on board privateers? On balance, there is reason to believe they could have. There are numerous reports demonstrating that over the course of the war the Naval Militia became competent, if not spectacular sailors. With the exception of the incident on board the Yosemite, there were few outstanding instances of poor service by the Naval Militia while at sea. The lack of professionalism so often levied as a criticism against the Naval Militia would have been a moot point on board a privateer. The men of the Naval Militia may not have been the best sailors at sea but their performance suggests that they would have offered comparable service to the crews of privateers from the late eighteenth century.

The examples of the vessels chartered by the United States Navy as auxiliaries demonstrate that privateering was not technologically outdated by the Spanish-American War. The United States effectively used private vessels during the conflict, recruiting the American line ships as scouts, transports, and cable-cutters. Private citizens also served with competency during the war. The crews of the American Line ships manned the steamers all through the war and received high praise from the naval captains for their service. The Naval Militia received mixed reviews from the officer corps after the war, but their performance suggests that private citizens with little-to-no sailing experience were able to provide adequate service on modern steam-powered vessels. While it would have been more difficult for privateers to outfit and sail during the Spanish-American War than it had been during the age of sail, evidence suggests that it was still technologically feasible. To understand why neither belligerent commissioned privateers, we must rather look to the diplomatic and strategic circumstances surrounding the practice of privateering and the Spanish-American War.

The Declaration of Paris and the “Barbarous Warfare” of Privateering

The Spanish-American War was a bilateral conflict, but one in which both belligerents were in constant talks with potential allies. Both Spain and the United States needed to court favor from the European Powers: Spain in an effort to forge an alliance, and the United States in the hopes of ensuring Europe’s continued neutrality. It was in part because of these diplomatic goals that neither side commissioned privateers. European statesmen and merchants had long seen privateering as a barbaric and outdated form of warfare and would doubtless look unfavorably on whichever power resorted to the practice. A brief investigation of the events surrounding the Declaration of Paris will demonstrate Europe’s animosity towards the practice of privateering and will explain why neither belligerent commissioned privateers during the Spanish-American War.

The Declaration of Paris grew out of discussions on maritime regulations following the Crimean War. During the war, Britain broke with tradition and agreed to abide by the “free ships free goods” principle, which precluded the seizure of neutral vessels carrying enemy cargo. The United States staunchly supported the principle and after the war opened negotiations to make the practice a staple of international maritime law. It was not the first time the United States fought for neutral shipping rights; in a letter to British Foreign Secretary George Canning written in 1823, then-Secretary of State John Quincy Adams argued that “this search for, and seizure of, the property of an enemy in the vessel of a friend is a relict [sic] of the barbarous warfare of barbarous ages,” and proposed a complete abolition of private war at sea. Britain did not want to give up their right to seizure without receiving something worthwhile in return; they proposed to relinquish their traditional practices and accept “free ships make free goods” permanently if the United States agreed to abolish the practice of privateering.

Britain had a number of reasons for seeking the abolition of privateering. Privateers were a real threat to British naval strategy. A large number of small, fast commerce-raiding privateers could attack shipping lanes where the Royal Navy was absent and vanish before the Navy could respond. Britain had a large merchant marine and vast commercial networks; eliminating the threat of privateer attacks on British trade would allow the Royal Navy to focus its efforts on hunting down the enemy navy and blockading an opponent’s home ports. Queen’s Advocate J.D. Harding advised Queen Victoria that the abolition of privateering would be “a great advantage to the civilized world in general, and of peculiar value to Great Britain, especially in case of a war with the United States,” which had effectively used privateers against the British in two prior wars. The eradication of a privateering threat would make a possible war with the United States much easier and would in general play to the advantage of British naval planners.

The mercantile community strongly favored privateering’s abolition. Privateering was unquestionably bad for business; lucrative merchant ships were the main targets of privateer attacks. Even if the cargoes made it to their destination safely, war always brought with it a spike in insurance rates which cut heavily into profits. On March 13, 1854, the Liverpool Chamber of Commerce issued a resolution calling for Britain to renounce privateering. MP Thomas Horsfall brought the resolution to the attention of the House of Commons four days later. The abolition of privateering would remove a dangerous threat to the merchant community, allowing for more freedom of trade on the oceans and, in turn, more profit.

Eradicating the practice of privateering had a moral quality to it as well. In a letter to the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Earl Clarendon, First Lord of the Admiralty Sir James Robert Graham spoke of the “advance of civilization” that would come from the elimination of the practice. In the same letter, he compared privateering to the slave trade, a practice that was outlawed by Britain in 1808. “The using of letters of marque,” Graham argued, “tends to foster a mercenary, violent, and lawless spirit, uncurbed by any social or moral control, which soon degenerates into that of a pirate.” Graham’s arguments apparently swayed Clarendon; in the House of Lords, Clarendon compared privateers to “pirates, the common enemies of mankind,” and later called the practice “the fruitful source of iniquity and misery in its worst form.” Privateering negatively impacted British strategy, business, and morality, leading many from Britain to lead the charge for its abolition.

The Declaration of Paris was announced on April 16, 1856 with the first article reading “Privateering is, and remains, abolished.” In their minds, Europe had achieved a major step forward economically, strategically, and morally with the abolition of privateering. Forty-five states agreed to the Declaration, but two notable exceptions were the United States and Spain. Both countries agreed on the other three articles of the Declaration regarding the rights of neutrals at sea and the legitimacy of blockades, but neither side would relinquish the right to privateering. The United States argued that since their navy was far weaker than the largest navies of Europe, their only hope to contend with European powers in a maritime struggle was through the reliance on privateers. Spain’s position was directly related to that of the United States. Should a conflict arise between the United States and Spain where the Americans sent privateers against Spanish colonial possessions in the Caribbean, Spanish authorities wanted to withhold the ability to defend their possessions in the same manner.

The performance of Confederate privateers in the American Civil War demonstrates the suffocating diplomatic effect the Declaration had on the practice. Just five days after the Battle of Fort Sumter, Confederate President Jefferson Davis began accepting applications for letters of marque. Fear spread through the Union mercantile community, with some frightened reports claiming that Confederate privateers were preparing to sail from Spain and England. Union representatives sought to have the privateers condemned as pirates in Europe; Secretary of State Seward even suggested that the United States may sign on to the Declaration. to Russell [British Foreign Secretary], 27 April, 1861, in Tracy, Sea Power and Trade, 43. Lyons believed the suggestion was in bad faith, writing “The time at which the offer would be made renders the thing rather amusing.”] Such an action was never carried out, and in the event the Union did not need to in order to neutralize Confederate privateers. The European powers maintained a strict neutrality in the Civil War and banned the sale of any prizes in their ports. Privateers relied heavily on the sale of prizes to produce profits; with nowhere to sell the spoils of war internationally, Confederate privateers struggled to operate anywhere outside of the American South. As William Robinson Jr. notes, the decision’s “effect upon the United States was vastly less injurious than upon the Confederate States.” Owing to the diplomatic restrictions Confederate privateers operated almost exclusively in their home waters and by 1862 had largely disappeared from the war. Though the Declaration of Paris failed to outlaw privateering worldwide, it had succeeded in neutralizing the impact of privateering and keeping the vessels out of European waters.

Since the Declaration of Paris in 1856 privateering had all but been eradicated in Europe, much to the approval of the Great Powers. European navies did not rely on privateering for naval defense; some, like Britain, were certainly better off strategically without the possible threat of privateers. Merchants rested a little easier knowing that their goods would not be seized in transit by roguish individuals on the high seas, while some merchants campaigned to take maritime law a step further and eradicate all seizure of private property. Politicians and pressmen alike trumpeted the advance of civilization with the eradication of a barbaric and cruel practice that was seen as an outmoded relic of warfare. Privateering was immoral, impracticable, and illegal to Europe, and since both the Spanish and the United States needed to curry favor from the European states during the 1890s, it made sense for both to avoid the practice altogether.

For the Americans, commissioning privateers may have escalated a conflict that was in many ways unwanted to begin with. During the election of 1896 William McKinley ran on a strong economic platform, representing the gold interests and a rebuild of the economy after the Panic of 1893. He had little-to-no foreign policy experience, and in none of his campaign speeches did he address the growing Cuban issue that would eventually lead to war with Spain. As late as April 1898 McKinley and his diplomatic staff were working with the Spanish to secure an armistice in the Cuban conflict, but McKinley eventually bowed to the domestic pressures of his Congress and turned the initiative to declare war over to them. Once war was declared, the Americans wanted to ensure that the conflict would remain a bilateral affair. The United States was widely recognized as having the superior navy; given that, and Europe’s distaste for privateering, issuing letters of marque would have been seen as vindictive, antagonistic, and unnecessary. The diplomatic actions of the United States after the war demonstrate their desire to do away with privateering; at the Hague Conference of 1899 they introduced a motion to make private property at sea immune from attacks. By announcing at the onset of the conflict that no privateers would be outfitted for the war, the United States eased the worries of Europe’s mercantile community, and in avoiding a disagreement with the Europeans over the controversial practice, ensured their continued neutrality. Spain too needed to garner favor from the European powers, but their diplomatic tactics were rather more complex.

The Righteous Victim: Spain’s Contradictory Diplomacy over Privateering

In a letter written shortly after the Maine incident, Admiral Cervera wrote to Minister of the Marine Segismundo Bermejo, “A campaign against [the United States] will have to be, at least for the present, a defensive or a disastrous one, unless we have some alliances, in which case the tables may be turned.” The balance of military power in the war tilted decisively towards the Americans, and Cervera was correct in stating that Spain’s only realistic hope of victory was to establish an alliance with one of the other European states. In an attempt to gain support from one or more of the Great Powers, Spain positioned itself as the just and righteous defender of honor, a law-abiding victim of the bellicose and imperialistic Americans. In doing so, the Spanish hoped to turn diplomatic opinion against the Americans, and increase the sympathies for their own side. Authorizing privateers, an act made illegal by customary law in the Declaration of Paris, would have comprehensively undermined Spain’s diplomatic strategy and would have likely turned the sympathies of Europe against the Spanish.

With the explosion of the Maine in Havana Harbor pushing the two sides closer to war, Spain sought to emphasize their innocence to other European powers. Whereas the Spanish believed the incident to be “purely accidental,” American yellow journalists were quick to accuse the Spanish of treachery, allegations that Spain categorically refused. In a letter to Spanish ambassadors, Minister of State Pío Gullón e Iglesias requested that the ambassadors “invite attention” to the unfounded press reports which were “arousing a spirit of menace in the relation of that Republic with Spain.” Both states formed commissions to investigate the cause of the explosion; the Spanish complained that their inquiry was impeded by “the refusal to establish the necessary cooperation” between the two commissions. The two sides naturally came to different conclusions; the Spanish believed the explosion was internal, while the Americans found that the source of the blast came from outside the hull of the ship. The Spanish saw the discrepancy as an example of American treachery in the face of Spanish morality, a view they were quick to push upon other European powers.

In late March, Gullón attempted to garner outright European support for Spain against the Americans. In his letter he used what would become the standard Spanish diplomatic ploy during the war: positioning Spain in the moral right against US aggression, while threatening that war may have adverse effects on the Great Powers.

So convinced is Spain of her right…and of the prudence with which she is acting that…she will not hesitate to at once ask the counsel of the great powers and, in the last resort, their mediation to adjust the pending differences, which differences, in the near future, may disturb a peace that the Spanish nation desires to preserve as far as its honor and the integrity of its territory will permit, not only on its own account, but because war, once begun, affects all other powers of Europe and America.

Gullón’s pleas had little effect; the Great Powers expressed their sympathies but chose to remain neutral. The only action they undertook was to send a weakly-worded demarche to the United States government “appeal[ing] to the feelings of humanity and moderation of the President”; this letter was criticized by the Spanish for being too considerate to the Americans.

In mid-April, as war became inevitable, the language used by Spanish diplomats became more extreme. In a letter to his ambassadors on April 14, Gullón spoke of the “irritating and groundless charges against Spain” levied by the US House of Representatives, and asserted that Spain “has gone to the extreme in its moderation and painful sacrifice to maintain and facilitate peace.” Four days later Gullón sent another memo to his ambassadors including “a statement of the facts up to this time” regarding Spanish-American relations over the Cuban insurrection. The document detailed the methods used by the United States “for encouraging the fratricidal struggle” in Cuba and explained how the Americans “skillfully exploited” the Maine explosion “to provoke a conflict between Spain and the United States.” It continued on to describe the “fresh and painful sacrifice” of concessions made to the United States by Spain, concessions that the power-hungry Americans would not accept. The letter concludes, “His Majesty’s Government only desire to make known to the civilized world that reason and right are on their side and provocation and injustice on that of the United States.”

Once the war began, Spain took note of every supposed American transgression, bringing them to the attention of the European powers in the hopes of garnering sympathy for their cause. One of the major points of contention was the declaration of the Cuban blockade. Officially, the Congress of the United States declared war on Spain on April 25, 1898. However, on April 22 McKinley had declared the blockade of Cuba, and vessels of the United States Navy had begun to take Spanish ships and apply for prize money from those captures. McKinley, then, had technically authorized warlike acts before war had been declared; to remedy this, Congress backdated the declaration, stating on April 25 that the state of war had existed since April 21. In a letter detailing Spanish grievances to foreign powers, Gullón called this a “strange and unlawful particularity.” The consequences of the war’s declaration were more than semantic. Given that Spain deemed the retroactive war declaration unlawful, every seizure of a ship between April 21 and April 25 was also illegal. In the aforementioned letter Gullón specified nine Spanish vessels that had been taken in that time span and also included “any others which may have taken place prior to April 25.”

Spain also claimed that the ineffectiveness of the Cuban blockade made it illegal. According to the Declaration of Paris, “blockades, in order to be binding, must be effective – that is to say, maintained by a force sufficient really to prevent access to the coast of the enemy.” The US blockade officially commenced on April 22, but Gullón provides a list of seven vessels that sailed past the blockade between April 22 and May 7. If the blockade was ineffective to begin with, it was all but nonexistent when Rear Admiral William Sampson, commander of the squadron blockading Cuba, took his fleet to Puerto Rico to scout for Admiral Cervera’s Spanish force. Any interruption in the blockade required a new notification once the blockade was reestablished; Spain received no word as such from the United States.

In constantly reporting perceived American violations, Spain sought to turn support against the United States and gain enough sympathy that one of the European powers would support her in the war. The strategy succeeded, in part; Austria expressed intentions of helping to end the war but never received wide European support. France was instrumental in communicating Spain’s desire for a ceasefire with the Americans to bring about a quick end to the war. While Europe may have been sympathetic, Spain’s diplomatic strategy was not effective in bringing a strong ally into the war.

Throughout the Spanish-American conflict Spain positioned itself as the just victim of American aggression; why, then, did Spain explicitly reserve the right to commission privateers, rather than renounce the practice entirely as the United States had done? Perhaps Spain, fearing the worst in the coming war, wanted to be able to resort to privateering should the Americans launch an attack on the Iberian Peninsula; however, as the war ended before the Eastern Squadron set sail, this is impossible to prove definitively. What is clear is that throughout the course of the war, Spain used the threat of privateering in an attempt to leverage both the Great Powers of Europe and the United States.

On April 24 Gullón sent a missive to his ambassadors detailing the Spanish declaration of war. The section regarding privateering is of particular note:

Regarding privateering, your excellency should state, confidentially, that although the Government of His Majesty reserves absolutely its right it does not intend to exercise it for the present, unless the neutral powers do not observe the strict neutrality prescribed by the law of nations. The Government of His Majesty trusts that this generous concession on its part will be duly reciprocated by friendly powers, and that they will see in it a new proof of the correct procedure of Spain, who desires to demonstrate that in all its acts it is influenced by justice and right.

Once again Gullón emphasizes Spain’s position of “justice and right” in their decision to refrain from privateering. However, they would resort to the practice if the Great Powers did not remain neutral in the war. If Spain could not forge a European alliance, it could at least ensure that its opponent remained isolated too. The language of the letter contains more of the same Spanish diplomatic posturing, while the spirit of it implies a simple threat: remain neutral, or privateers will devastate European commerce.

Spain’s threat was not directed at all of Europe, but at one power in particular, the state that was the most likely to form an alliance with America: Britain. During the 1890s Britain found that its interests lined up with those of the Americans. An increased American presence in the Far East would help to balance the rising power of Germany in the region, and open the door for further British expansion there. When American ambassador to Spain Stewart Woodford broke off official relations with the Spanish, he left the British embassy in charge of American interests in country. The press were quick to seize upon rumors of an Anglo-American alliance against the Spanish in the coming war. On May 13, those rumors appeared accurate when British Minister for the Colonies Joseph Chamberlain proposed that the war between Spain and the United States could help bring about an Anglo-Saxon alliance. The British never broke from their commitment to neutrality, but it was clear that their sympathies lay with the Americans.

Britain too had the most reason to fear a return of privateering. Britain still had one of the largest merchant marines in the world, and had close trading ties with the United States. Of particular interest to the British were American ships carrying wheat and cotton to the British Isles; attacks on these ships by Spanish privateers would disrupt the British food supply and textile industry. Spanish privateers could pose major disruptions to British trade and may well have forced Britain into the war, thus hurting Britain’s diplomatic standing with the rest of Europe. Preserving the right to commission privateers allowed Spain to use the practice as leverage against Britain and the other European powers without ever having to resort to privateering or to stray from the already-established diplomatic strategy of appearing as the just and righteous power in the war against the Americans.

Maintaining the right to use privateers allowed Spain to leverage the United States with threats of the practice as well. Up and down the American coastline there was widespread fear of Spanish naval raids, giving Spanish agents a grand opportunity to create unrest among their opponent’s populace. One notable example of Spanish agents using the threat of privateering comes from British Columbia. The province had a number of small inlets and harbors, making it almost impossible for the authorities to track down potential privateers. The lucrative Yukon gold trade also ran just off the coast of British Columbia and down into the Pacific American coast and was an enticing prize for any privateer. Spanish agents in the region spread rumors tothe local press about the presence of a Spanish privateer, and sent encoded telegrams that were intercepted by the Americans referring to Spain’s intention to purchase ships in the region. No privateer ever sailed from British Columbia during the war, and the affair had no major effect on the war’s outcome; however, the “phantom privateer” in the Yukon demonstrates that by refusing to renounce privateering, Spain enabled its agents use the practice to spread concern along the American coast.

Spain could not commission privateers during the war with America in 1898 because doing so would utterly undermine the diplomatic strategy Spain was pursuing. Before and during the war, Spain sent a steady stream of memoranda and letters to the Great Powers of Europe detailing the “real” nature of the conflict as a war of imperial aggression on the part of the United States against Spain, the peaceful monarchy that had done all it could to avoid an unjust war. Commissioning privateers would have been contradictory to the role Spain had created for itself; however, privateering was still an effective tool as a threat. Spain did not renounce privateering altogether because it intended to use the threat of privateering to leverage both the European powers and the United States. Though Spain’s threats of privateering did achieve some minor successes, they had little effect on the overall war effort.

Professionals and Privateers: American Naval Strategy in the War with Spain

For the United States Navy, the question of privateering was never in doubt: the Navy did not want privateers, nor did it need them. Leading up to and during the war, the Navy worked to remodel itself as a first-class, professional navy, a notion entirely contradictory to privateering. Largely because of these improvements the US Navy was far superior to the Spanish Navy by the start of the war and did not need to resort to commerce raiding to cripple its opponent. The strategy for the war, which was planned out well in advance of the actual conflict, was predicated on gaining control of the waters around Spain’s colonies and not destroying Spain’s trade networks. Even for coastal defense the US Navy used other auxiliary vessels, negating the need to use privateers to protect major American ports. The attitudes and actions of the Navy Department regarding the war with Spain effectively eliminated privateering from the conversation in American naval strategy.

Long before the first signs of war with Spain arrived, the US Navy had worked towards the establishment of a more professionalized naval officer corps and department as a whole. During the 1880s the Navy created the ABCD fleet made up of the modern warships Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, and Dolphin. The Office of Naval Intelligence was established in 1882 and would play a major role in the war providing information on Cervera’s fleet and the Spanish Navy at large through their network of naval attaches placed in the capitols of European powers. Two years later, the Naval War College opened. The brainchild of Rear-Admiral Stephen B. Luce, the War College sought to educate officers in “the higher branches of the naval profession,” including strategy, history, and international law. Writing just after the war, Englishman H.W. Wilson believed the main strength of the US Navy was its professionalism and conduct, calling the American naval officers “intelligent, brave, and resourceful.” Since the 1880s the American Navy was trending towards a more professional and sophisticated organization, and the officers prided themselves on the quality of their service. A hearkening back to the banditry of privateering would have been a complete about-face for the Department and would have run contrary to their intention of creating a professionalized fighting force.

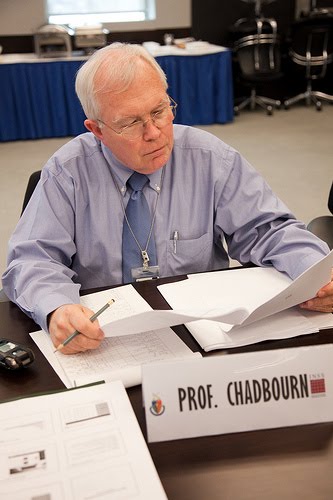

Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan was a proponent of battleship tactics, and was skeptical of the success of commerce-raiding tactics. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

In the years before the war with Spain American naval strategy shifted towards an increased use of battleships accompanied by lightly armed cruisers. Much of the impetus for this new direction came from Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan. In his seminal work The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660-1783, Mahan spoke at length of the merits of large fleet action as opposed to a strategy predicated on commerce raiding. He concluded his analysis by stating:

It is not the taking of individual ships or convoys…that strikes down the money power of a nation; it is the possession of that overbearing power on the sea which drives the enemy’s flag from it, or allows it to appear only as a fugitive; and which, by controlling the great common, closes the highways by which commerce moves to and from the enemy’s shores. This overbearing power can only be exercised by great navies.

The benefits of a large navy were more than strategic; leaders like Theodore Roosevelt saw a powerful navy as a necessity for the pursuit of America’s imperial ambitions. To truly be considered a great power, America needed a world-class navy. The two men played major roles in the Navy’s strategy during the war with Spain; Theodore Roosevelt served as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, while Captain Mahan was a member of the Naval War Board. Their influence led to an emphasis on the role of the battleship in naval grand strategy, and steered America far away from the unprofessional and inconsistent practice of privateering.

The improved efficiency and competency of the US Navy meant that, out of all the military branches of either belligerent, it was the most prepared for war with Spain in 1898. In 1894, a year before the Cuban Revolt even began, Captain Henry C. Taylor gave his students at the Naval War College an exercise asking them to formulate a strategic plan of war against Spain, including the “principal objectives” of both sides and bearing in mind tactical considerations such as coal and railroad operations. That same year Lieutenant Commander Charles J. Train drafted a potential operational plan for war with Spain. He accurately predicted that a Spanish offensive against the US coast was “most improbable,” and that “command of the sea would play an all-important part” in a war over Cuba. Train also was one of the first to propose the idea of a blockade of Cuba in his plans, suggesting a “strict blockade” of Havana, Matanzas, Saguala Grande, and Cienfuegos. In 1896 Lieutenant William W. Kimball issued a similar plan, detailing that the war would grow out of a conflict over the fate of Cuba and suggesting that the Navy’s primary objective should be to target the Spanish fleet as it made its way into Cuban waters. In his own plan of action the same year, Taylor concurred that the main theatre of operations would be the Caribbean but warned that “an attack on Cuba cannot be successful through a blockade alone.” A Naval Board that evaluated Taylor’s plan of action in December 1896 chose to add a “European squadron” to make demonstrations against the Spanish coast; this plan was never carried out, though the idea of making direct attacks on Spain never fully disappeared during the war.

The foresight of the US Navy is notable in and of itself, but of particular interest to this study is the complete lack of privateer operations in each of the plans. Train’s plan called for three fleets, one of which would be comprised of “cruisers and armed merchant ships” and which would be used primarily as a blockading force. Kimball too called for an “auxiliary fleet” comprised of “fifty auxiliary cruisers” and “twelve to twenty yachts and small steam craft in commission for despatch [sic] and look-out vessels.” He believed such a force was best equipped to “meet [a] fleet of 20 Spanish naval small craft and privateers”; Kimball assumed that while the Americans would abide by the Declaration of Paris, Spain would outfit privateers. Taylor’s sketches offered no suggestions on privateers and only briefly mentioned an auxiliary fleet, “which of necessity we must employ.” The Board’s plan of 1897 also neglected privateers but spoke of “light vessels” which could be employed as blockading ships and “must be drawn from the merchant service.” While the early plans for war did not seem to consider privateering a viable strategic option, they all appreciated the necessity of outfitting private merchant vessels as auxiliaries to the primary capital ships.

The diplomatic fallout from the Maine explosion encouraged the Americans to ramp up their preparations for war. On March 9 Congress appropriated fifty million dollars for the national defense, $29,973,274.22 of which was used by the Navy Department. The funds were used to secure “such vessels as might be desirable for purchase” to add to the auxiliary fleet; a full list of purchased vessels can be found in the Secretary of the Navy’s Report from 1898. Of particular note are the Amazonas and the Almirante Abreu; the American government purchased the two ships from Brazil in March and renamed them the Albany and the New Orleans. The Spanish had been eyeing the same vessels and were putting money together to purchase them from Brazil before the Americans swooped in and beat the Spanish to the punch. Private donations also bolstered the ranks of the United States Navy; William Randolph Hearst and F. Augustus Schermerhorn both donated their yachts to the Navy for the duration of the war. In their preparations for the war the US Navy was proactive in searching for additional vessels to add to their fleet, finding new ships from both foreign nations and domestic businessmen, along with a number of ships from the American merchant marine. These kinds of vessels, particularly the small and fast ships of the merchant service, would have likely been the preferred vessels of privateers had they been commissioned during the war. With the US Navy’s actions, those private ships found a home within the ranks of the Navy, not in the hands of private individuals.

Spanish Admiral Pascual Cervera was skeptical of privateering’s compatibility with modern steam-powered warships. (Naval History and Heritage Command photo NH 120476).

When the two sides declared war in April, the United States had a clear plan of operations for their fleet. Commodore George Dewey was immediately ordered to “proceed at once to the Philippine Islands [and] commence operations at once, particularly against the Spanish fleet.” President McKinley ordered the blockade of Cuba on April 21 and deployed Rear-Admiral Sampson and the North Atlantic Fleet to the Caribbean. The main objective was the destruction of the Spanish fleet under Cervera, which was expected to appear in the West Indies sometime in the spring. Held in reserve was the Flying Squadron under the command of Rear-Admiral Schley. Schley’s fleet gave the United States more flexibility in their deployment; once Cervera’s fleet manifested itself, Schley and Sampson could converge and eliminate the threat from Spain’s navy in one single action. With Cervera’s fleet destroyed, it would be possible for the US Army to move safely across the Caribbean and land in Cuba or Puerto Rico. No part of the US Navy’s strategy called for commerce raiding in the privateer style. Capital ships under Sampson (and after his deployment to the Caribbean, Schley) would cripple commercial networks running in and out of Cuba through the blockade, following Mahan’s emphasis on battleship tactics discussed earlier. Privateers and their style of commerce raiding had no place in America’s naval strategy for the war with Spain.

In the 1850s the primary reason given by the United States for refusing to agree to the Declaration of Paris was the need to rely on privateers to protect the country’s coast and maritime commerce. While there was never a strong campaign to revive privateering for coastal protection, there was a genuine fear of Spanish attack on the Eastern seaboard. Local merchants and business leaders feared the war would jeopardize their seaborne trade and hamstring the coastal economy. Charles B. Church, a shipping magnate based in Washington, DC, had even requested that the navy employ a convoy system to protect Atlantic trade. Most naval strategists thought it highly unlikely that Spain would send the bulk of its forces to attack the American coast. Captain Alfred Mahan called the public fear of attack “preposterous and humiliating terrors,” while Captain Caspar Goodrich stated that “our worst foe is ‘uninstructed public opinion.’” Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt was of the same mind and by his own word “urged the President and the Secretary [Long] to pay absolutely no heed to the outcries for protection from Spanish raids.”

Though it seemed highly improbable that an attack from Spain would be forthcoming, the Navy felt obligated to do something to provide for the common defense; to that end, it created the Northern Patrol Squadron and a mosquito flotilla. Commodore John A. Howell commanded the Squadron, and the San Francisco and auxiliary cruisers Prairie, Dixie, Yankee, and Yosemite comprised its main components. Commander Horace Elmer organized and led the mosquito flotilla until his death in April, at which time Rear-Admiral Henry Erben took command. Coastal defense gunboats and monitors composed the principal ships of the mosquito flotilla, which was organized into nine districts along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. The ships of the mosquito flotilla largely remained in their home districts, while the Northern Patrol Squadron cruised up and down the entire Eastern seaboard. The Northern Patrol Squadron and the mosquito flotilla were in many ways more theater than defense. In his patrol orders to Captain Theodore Jewell of the Minneapolis and Captain James Sands of the Columbia, Secretary Long stated:

The object of this cruise is to reassure the inhabitants of the cities and towns on the New England coast by showing a few of our vessels in their vicinity. Therefore it is important to either enter the harbors, or to send in a boat to get the mail, or communicate with the local authorities, or make such inquiries regarding the enemy’s vessels as will demonstrate to the people the fact that one of our ships is on the lookout in the neighborhood.

As H.W. Wilson stated after the war, the mosquito flotilla may have been sparsely armed, but successfully “reassure[d] the timid and ignorant.” With the two squadrons and well-equipped coastal fortifications protecting the Eastern seaboard, the Navy could appease the public outcry for protection at relatively little cost to the main theatre of operations in the West Indies and without having to outfit privateers for the same purpose.

To crew the numerous ships in the mosquito flotilla and Northern Patrol Squadron, the Navy drew on state-based naval militias. The men of the Naval Militia were given a modicum of training and dispatched aboard ships for duty, primarily serving with the deep-sea auxiliary cruisers and the mosquito flotilla monitors. In his report of 1898 Secretary Long states that “the personnel of the [Auxiliary Navy] was almost entirely contributed by the Naval Militia organizations of the various States,” and that additionally “a small percentage was supplied by the merchant marine.” Nearly 4,000 sailors served in the Naval Militia during the war, with over 1,500 coming from New York and Illinois alone. Though the militia operated with mixed results – as seen earlier in this essay – naval strategists saw “the imperative necessity for the maintenance of a national Naval Reserve.”

The Naval Militia was just one of the many ways the United States Navy eliminated the need for privateering and took from the same sources that privateers would have tapped during the war. Privateers would have needed ships, men, and a place in the grand strategy of the Navy; they found none of that during the Spanish-American War. The increased professionalism of the American Navy and its growing reputation abroad negated any possibilities of a privateering campaign, as shown by the actions of the Navy Department before and during the war. None of the plans for war dating back to 1894 gave any thought to America using privateers, or even partaking in commerce raiding outside of a blockade of Cuba. As war drew near, the Navy Department bought and outfitted any vessel it could find that would provide some use in the war, leaving the cupboard bare for any potential privateers looking to purchase seaworthy cruisers. By commissioning officers and sailors in the Naval Militia to join the Auxiliary Fleets, the US Navy eliminated a vital source of manpower that privateers would have needed to operate. The efficiency of the Navy Department and its grand strategy utilizing auxiliary cruisers demonstrates neither a desire nor a need for privateers on the American side during the Spanish-American War.

Honor for want of a Ship: Spanish Naval Strategy in 1898

Privateers were most often commissioned by the side with the weaker navy. Privateers were cheaper, required less direct control, and could prove devastating to enemy commerce, though they were all but hopeless against enemy warships. The Spanish Navy was recognized as the weaker force in the war; on paper it was only superior to its American counterpart in speed, but as German Rear-Admiral Plüddemann wrote, “It is doubtful…whether Spanish ships ever actually possessed the speed officially claimed for them.” With a weaker naval force, perhaps Spain could have benefited strategically from the use of privateers. Most of the American fleet was operating in the Caribbean and the Philippines, leaving American commercial routes in European waters exposed to possible attack. Privateering may have also demoralized the American people and brought a more satisfactory end to the war. Spanish artillery captain Severo Gómez Núñez believed that privateers could have separated the two American naval squadrons under Sampson and Schley and eased the pressure of the blockade, saying “there is no possible excuse to justify our not having taken advantage of this means of warfare.” There was potential strategic upside for Spain to commission privateers, yet they never issued letters of marque. The Spanish did not have the resources necessary to stage a privateering campaign, and given their attitudes regarding honor in war it is unlikely the Spanish would have resorted to the practice even if the resources had been at their disposal.

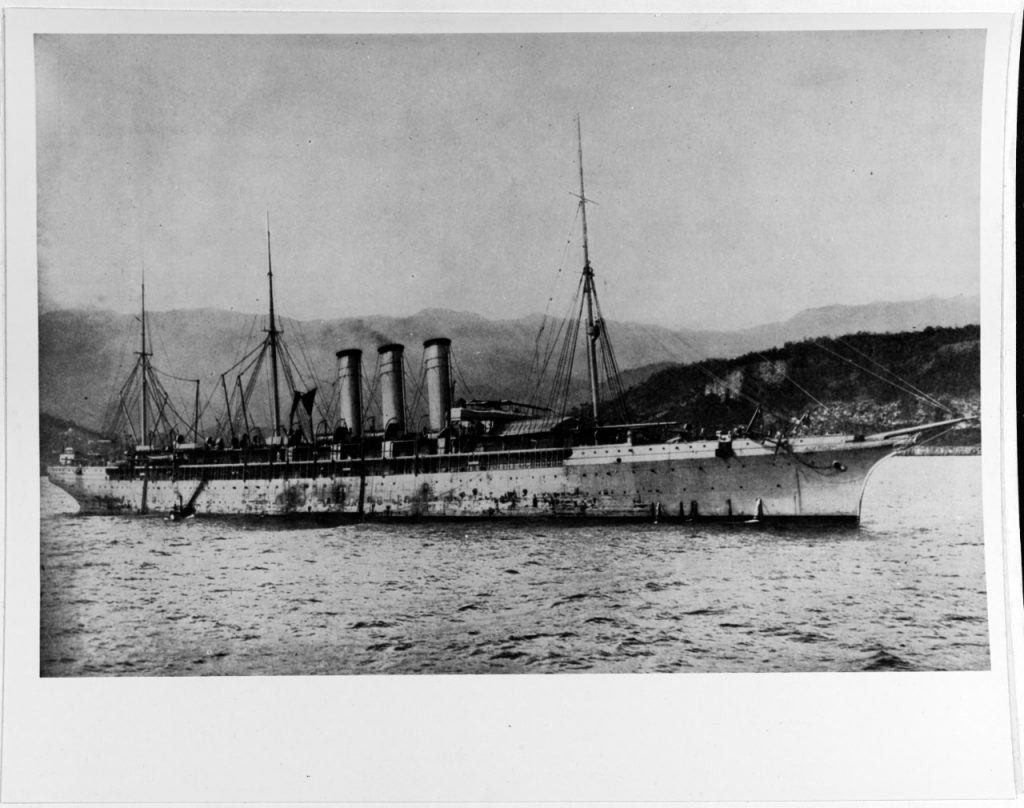

In the Naval Annual of 1899, Sir George Clark wrote, “In Spain, some efforts of preparation [for war] were made, but want of money, of resources, and of administrative capacity proved fatal.” Clark’s assessment is entirely accurate; where the US Navy was well-prepared for the war, the Spanish Navy floundered. Ship construction and outfitting lagged sorely behind schedule. In a letter to his cousin, Admiral Pascual Cervera cited the example of the Cataluña, a ship that had been under construction for eight years and still lacked a completed hull. He noted that the Carlos V, a ship entirely of Spanish construction, “is not what she should be,” if not entirely “a dead failure.” In his letters to Bermejo in the early part of 1898, Cervera predicted that a number of Spanish capital ships would be unfit to sail by the time his squadron departed. He was correct; upon receiving his orders to sail to Puerto Rico, the Pelayo, Carlos V, Vitoria, and Numancia were all incomplete or ill-equipped for the voyage. The armaments on board the ships were poor as well; the Cristobal Colón, which Cervera called “no doubt the best of all our ships,” did not have her heavy guns, nor did the crew have any 5.5-inch ammunition needed to fire the new, lighter guns. In the months preceding war with America, Spanish ships were on the whole poorly constructed, in states of disrepair, and possessed weaker armaments, a testament to the dilapidated state of Spain’s maritime power. Materials and armaments to outfit public ships before and during the war were sparse and poorly administered; it is unlikely that any significant amount of resources could be found to outfit private ships in their place.

In many ways Spain’s problems in outfitting its fleets can be tied to its finances, or lack thereof. Spain was economically in dire straits before and during the war in 1898. Though the monarchy had stabilized the government in 1875, old political rivalries between the Liberals, Conservatives, Carlists, Republicans, Basques, and a host of other interest groups meant Spain was never internally unified and struggled to find the stability necessary for strong economic prosperity. Most of Spain’s trade was with its colonies rather than with other European powers. With insurgencies growing in power and scope in both Cuba and the Philippines in the 1890s, that trade was running perilously low. By January of 1898, Cervera was able to state that Spain was “absolutely penniless,” particularly compared with the United States. The war only made the situation worse – principally for the lower classes, as the price of food increased and poor men were inducted into the military. In early May, the citizens of Gijon rioted over the price of bread, and the Civil Guard had to impose martial law. Spain simply was not a wealthy state, either in the public or private sector. The lack of funds prevented the Spanish Navy from effectively preparing for the war with America, and likely would have precluded any potential privateering expeditions from outfitting successfully.

If the situation in Spain was unconducive to the practice, the situation in the colonies – the main theaters of operations during the war – was hopeless. Insurrections in both Cuba and the Philippines had driven both economies to ruin. In a speech given to the Senate in March 1898, Vermont Senator Redfield Proctor described Cuba as a land of “desolation and distress, misery and starvation.” With the reconcentration policy placing all Cubans into the towns held by the army, there were few opportunities for public enterprise in Cuba in the lead-up to the war. As a result there were few Cubans who could legitimately stake their funds to privateer expeditions. In addition, the ships that were already in Cuba were of no use; Cervera wrote that “the eight principal vessels of the Havana station…have no military value whatever, and, besides, are badly worn out.” The Commandant-General of the Manterola Navy Yard in Cuba was of the same mind, stating that “of the fifty-five vessels composing this fleet thirty-two are auxiliary launches of little usefulness, even for police service on the coast.” Even if there had been a number of effective ships in Cuba, and enough money in country to fund privateer expeditions, the United States Navy took control of the waters off Cuba almost immediately after war was declared. Privateers operating from Cuban ports would have likely seen little success in the face of direct US opposition. What vessels that were seaworthy in Cuba were used with mixed results as blockade runners and posed no real threat to US sea superiority there. In the Philippines, US control was even more pronounced. Following Dewey’s victory at Manila Bay, Spain had no major harbors in the archipelago and was losing territory rapidly to the insurgents under Emilio Aguinaldo. There, the Spanish could only hope to hole up in Manila and wait for support from the homeland.

Spain did not have a viable option for outfitting privateers. In the Iberian Peninsula, maritime facilities had few ships to offer and were incapable of successfully outfitting ships for the Spanish Navy, let alone ships for private individuals. Economic difficulties made the practice unreasonable in Spain, and impossible in its colonies. Yet even if Spain did have a strong foundation from which to send out privateers, it is unlikely that Spanish leaders would have opted to use them. Running through nearly all the Spanish documents related to the war is an emphasis on fighting with honor; if Spain was going to lose its colonies, it would maintain its pride while doing so. With military leaders, statesmen, and press all putting an emphasis on honorable wartime conduct, Spain would never rely on such a dishonorable practice as privateering.

In response to reports of US military superiority over the Spanish in March, Madrid-based newspaper El Imparcial wrote, “such news items would weigh very little in one pan of a balance scale compared with Spain’s honor in the other pan.” Spain’s actions throughout the war were characterized by a strong desire to fight with honor, even at the expense of prudent tactical decisions. The General Ordinances of the Spanish Navy included an article stating:

You will fight as far as lies in your power against any superior forces, so that, even though necessary to surrender, your defense will be considered honorable by the enemy. If possible, you will run your ship aground on own or hostile coast rather than surrender, if there is no immediate risk of the crew perishing in the shipwreck; and even after running aground, it will be your duty to defend the ship and finally burn it, if there is no other way of preventing the enemy from taking possession of it.

When facing likely defeat in Santiago, Cervera was expected to follow these instructions. Captain-General of Cuba Ramon Blanco ordered Cervera to attempt to break the blockade, believing “it is preferable for the honor of arms to succumb in battle” than to possibly lose the fleet without a fight. Tactically, little could be gained from the attempt to run the American blockade, but following Blanco’s orders Cervera led his squadron out of Santiago on July 3, where he were resoundingly defeated by the Americans. In his telegram to Blanco informing him of the disaster, Cervera made a point to emphasize that the “gallantry of all the crews has earned the most enthusiastic congratulations of enemy.” If Cervera’s fleet had to be destroyed, Spain thought it best that it went down fighting rather than dishonorably surrender.

After Cervera was defeated, the Spanish Army’s position in Santiago was unsustainable. The US Army under Major General William Shafter approached General Jose Toral regarding a surrender; however, Toral was skeptical. He stated, “A solution [must] be found that leaves the honor of my troops intact; otherwise you will comprehend that I shall see myself obliged to now make defense as far as my strength will permit.” By July 15, the Spanish had decided that “the honor of our arms has been completely vindicated,” and were ready to give in to the Americans. The agreement between the two sides never used the term “surrender,” opting instead for the less extreme “capitulation,” and Article IX of that document stated “That the Spanish forces will march out of Santiago de Cuba with honors of war…” The timing of the Spanish surrender and the articles therein were primarily based on satisfying Spanish honor, a testament to the emphasis placed on the ideal by the Spanish military.

A similar occurrence happened in the Philippines, when the Spanish troops there surrendered in August. Trapped in Manila by Dewey’s fleet since early May and surrounded on all sides on land by a combination of American troops and Filipino insurgents, Governor-General Fermin Jaudenes sought to turn the city over to the Americans rather than let it fall into the hands of Aguinaldo’s fighters. However, the Spanish military code necessitated some form of resistance before surrender, at the risk of a court-martial upon their return to Spain. Jaudenes came to an agreement with Dewey whereby the Americans would bombard an unoccupied fort for an hour then advance their foot soldiers towards the city, at which point the Spanish would surrender. Both sides played their respective roles, and on August 14 the Spanish again capitulated “with all honors of war.”

Spain’s blind obedience to its principles of honor had its fair share of critics both at home and abroad. One of its staunchest opponents was Captain Victor Concas, commander of the Infanta Maria Teresa under Admiral Cervera. In the preface of his work he criticizes “political men” for their reliance on “romanticism and legends,” stating “that these are not the reality; that they do not now and never did constitute war, and that the nations which have had recourse to them have ended by disappearing from the map of the world.” Concas gives the example of Admiral Sampson’s decision to avoid the coastal batteries set up by the Spanish, saying that “We should have considered that cowardice,” and that Spain would seemingly have “preferred a squadron crippled and rendered useless by a glorious battle without any objective, to a squadron that has remained intact….” Concas bluntly states later in his work that “The object of military operations is final success and not proofs of valor. But it is useless to discuss this point, for it will never be understood in Spain.” Concas apportions blame for Spain’s failure to a number of parties, but lays the brunt of the blame on Spanish press and politicians for their haughty and foolish adherence to irrelevant ideals of honor and valor, principles that Concas believes were woefully out of place in the conflict with the United States.

Regardless whether or not Spain’s romantic interpretation of wartime conduct was detrimental to its cause, it is clear that Spain sought to fight the war according to its cherished principles of honor and righteous conduct. In some cases valorous conduct was deemed more important than tactical considerations. Privateering was not seen as a chivalrous practice in its heyday, and was unquestionably judged negatively in 1898. Even if Spain had the resources and administration necessary to stage a large-scale privateering campaign during the war, it is highly unlikely Spain’s ministers would have accepted the adoption of the practice as it contradicted the lofty ideals of war they aspired to follow.

Conclusion

No privateers ever sailed during the Spanish-American War, a conflict that lasted only a few months and resulted in a decisive victory for the United States. Despite arguments to the contrary it was still technologically feasible for a state to outfit privateers and send them against an enemy’s maritime commerce. The United States employed a system somewhat similar to privateering during the war, using private vessels crewed by volunteers and barely-trained seamen; however, they were careful to keep the vessels under the direct control of the Navy Department, a clear contrast to the practice of privateering. The reason for privateering’s absence from the war, then, cannot be the technological improvements of fighting vessels over the course of the nineteenth century. Privateering was outdated by the Spanish-American War because of diplomatic and strategic factors. With the nominal abolition of the practice with the Declaration of Paris in 1856, Europe took a strong stance against privateering and made the tactic untenable by closing its ports to privateer prize sales. As both sides needed the support – or, at the least, the tacit neutrality – of Europe’s Great Powers, outfitting privateers would have been a risky endeavor that may have necessitated armed intervention from Europe. Spain, in an inferior military position to the Americans, desperately needed support from the Great Powers and tried to use American transgressions of agreed-upon maritime practice as a tool to gain sympathy from other states on the continent. All the while, they maintained their right to outfit privateers should another power – namely, Britain – join with the Americans, and attempted to use the threat of privateers to leverage their diplomatic position. The US Navy neither desired nor required privateers to wage war against Spain. The improved professionalism and training of the officers of the United States Navy resulted in a wartime strategy that focused on battleship action and not on commerce-raiding tactics of privateers. To augment the main battle fleet, the Americans relied on auxiliary cruisers which were under direct control of the US Navy. While Spain, as the weaker maritime power, could perhaps have benefited from outfitting privateers, the country never had the naval infrastructure nor the material and financial resources needed to wage an effective privateering campaign, and their mindset that placed honor above tactical and strategic considerations suggests that they would not have resorted to the practice even if it had been feasible. Scholars cannot explain the disappearance of privateering throughout the nineteenth century by only looking at the advancements of technology. The example of the Spanish-American War shows that while privateering was still technologically possible, strategic and diplomatic considerations surrounding the conflict made the practice unthinkable for either side.

Bibliography

Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Year 1898. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1898.

Berner, Brad K., ed. The Spanish-American War: A Documentary History with Commentaries. Lanham, MD: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2014.

Bradford, James C., ed. Crucible of Empire: The Spanish-American War and Its Aftermath. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1993.

Cervera, Pascual. The Spanish-American War a Collection of Documents Relative to the Squadron Operations in the West Indies. Vol. VII. War Notes. Washington, DC: Office of Naval Intelligence, 1899.

Chadwick, French Ensor. The Relations of the United States and Spain: Diplomacy. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1909.

Chadwick, French Ensor. The Relations of the United States and Spain: The Spanish-American War. Vol. 1-2. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911.

Clarke, George. “Naval Aspects of the Spanish-American War.” In The Naval Annual, 1899, edited by T. A. Brassey. Portsmouth: J. Griffin, 1899.

Commander Jacobsen. Sketches from the Spanish American War. Vol. III-IV. War Notes. Washington, DC: Office of Naval Intelligence, Government Printing, 1899.

“Commons Sittings in the 19th Century.” Hansard 1803-2005. Accessed July 15, 2016. http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/.

Concas, Victor. The Squadron of Admiral Cervera. Vol. VIII. War Notes. Washington, DC: Office of Naval Intelligence, 1900.

Coogan, John W. The End of Neutrality: The United States, Britain, and Maritime Rights, 1899-1915. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981.

Correspondence Relating to the War with Spain: Including the Insurrection in the Philippine Islands and the China Relief Expedition, April 15, 1898, to July 30, 1902. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, U.S. Army, 1993.

“Documentary Histories: Spanish-American War.” Naval History and Heritage Command. Accessed July 15, 2016. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/publications/documentary-histories/united-states-navy-s.html.

Goodrich, Caspar F. “Scouts: Lecture Delivered, Summer Course, 1902.” NWC Lectures, Record Group 15, Box 1. Archives of Naval War College. U.S. Naval Station, Newport, R.I.

Hattendorf, John B., B. Mitchell Simpson, III, and John R. Wadleigh. Sailors and Scholars: The Centennial History of the U.S. Naval War College. Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, 1984.

Hilton, Sylvia L., and Steve J.S. Ickringill, eds. European Perceptions of the Spanish-American War of 1898. Bern: Peter Lang, 1999.

Howard, Michael, ed. Restraints on War: Studies in the Limitation of Armed Conflict. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Lemnitzer, Jan Martin. Power, Law and the End of Privateering. Houndsmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

“Letters of Marque and Privateering.” Liverpool Mail, March 18, 1854. British Newspaper Archive

MacQueen, John Fraser. Chief Points in the Laws of War and Neutrality. London: William and Robert Chambers, 1862.

Mahan, Alfred T. The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660-1783. Boston: Little, Brown, and, 1890. Accessed October 25, 2016. https://archive.org/details/seanpowerinf00maha.

Mahan, Alfred T. Lessons of the War with Spain and Other Articles. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1899.

Mahan, Alfred Thayer. Letters and Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan. Edited by Robert Seager, II and Doris D. Maguire. Vol. III. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1975.

Marolda, Edward J., ed. Theodore Roosevelt, the US Navy, and the Spanish-American War. New York: Palgrave, 2001.

The New York Times, April 25, 1898. Accessed June 28, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/big/0424.html#headlines.

Núñez, Severo Gómez. The Spanish-American War: Blockades and Coast Defense. Vol. VI. War Notes. Washington, DC: Office of Naval Intelligence, 1899.

Offner, John L. An Unwanted War: The Diplomacy of the United States and Spain over Cuba, 1895-1898. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

Plüddemann, M. Comments of Rear Admiral Plüddemann: German Navy on the Main Features of the War with Spain. Vol. II. War Notes. Washington, DC: Office of Naval Intelligence, 1899.

Reuter, Bertha Ann. Anglo-American Relations during the Spanish-American War. New York: Macmillan Company, 1924.

Robinson, William M. The Confederate Privateers. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1928.

Savage, Carlton, ed. Policy of the United States towards Maritime Commerce in War. Washington, D.C.: United States Printing Office, 1934.

Semmel, Bernard. Liberalism and Naval Strategy: Ideology, Interest, and Sea Power during the Pax Britannica. Boston: Allen & Unwin, 1986.

Sherrin, P.M. “Spanish Spies in Victoria, 1898.” BC Studies No. 36 (Winter 1977-78): 23-33.

Spanish Diplomatic Correspondence and Documents 1896-1900. Washington, DC: Office of Naval Intelligence, 1905.

Spector, Ronald H. Professors of War: The Naval War College and the Development of the Naval Profession. Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, 1977.

Starkey, David J. s.v. “Privateering.” The Oxford Encyclopedia of Maritime History. Edited by John B. Hattendorf. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Sumida, Jon Tetsuro. Inventing Grand Strategy and Teaching Command: The Classic Works of Alfred Thayer Mahan Reconsidered. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 1997.

Tejeiro, José Müller Y. Battles and Capitulation of Santiago De Cuba. Vol. I. War Notes. Washington, DC: Office of Naval Intelligence, 1898.

Tracy, Nicholas, ed. Sea Power and the Control of Trade: Belligerent Rights from the Russian War to the Beira Patrol: 1854-1970. Vol. 149. Navy Records Society Publications. Burlington, VT: Ashgate for the Navy Records Society, 2005.

Trask, David F. The War with Spain in 1898. New York: Macmillan, 1981.

“War with Spain — Maritime Law.” In Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 772-73. Vol. 63. Accessed July 18, 2016. http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/FRUS/FRUS-idx?type=article&did=FRUS.FRUS1898.i0025&id=FRUS.FRUS1898&isize=M.

Wilson, H. W. The Downfall of Spain: Naval History of the Spanish-American War. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company, 1900.

(Return to July 2018 Table of Contents)

Footnotes