Contents:

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Bibliography

Noah Hải Lâm Rice

National History Day

Có chí thì nên is a Vietnamese saying that means, “Where there is will, there is a way.” This describes the determination Vietnamese immigrants displayed in their exploration of new homelands after the Fall of Saigon. On April 30, 1975, after 20 years of fighting, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong took over Saigon, ending the war and reunifying Vietnam under one communist regime. Many South Vietnamese experienced risky journeys in order to explore new homelands and be free of communism. By the late 1980s, there were over 231,000 Vietnamese immigrants living in the U.S., with approximately 18,000 settling in Minnesota. The influx of refugees resulted in cultural exchanges as immigrants accepted Western ways of life, while trying to hold onto their Vietnamese heritage. At the same time, Minnesotans began to slowly embrace aspects of Vietnamese culture. These cultural exchanges between Minnesotans and Vietnamese immigrants helped pave the way for the immigrant groups of today.

The Vietnam War was a civil war between the North and South Vietnamese. France had occupied Vietnam since 1777, but in 1954, Ho Chi Minh, a communist revolutionary, led the fight against France for independence (Do 18). France granted Vietnam independence and later that year, as part of the Geneva Accords, Vietnam was divided into two nations along the 17th parallel (Appendix A). The North Vietnamese and Viet Cong (South Vietnamese communists) wanted to reunify Vietnam and model a united government after the communist nations of China and the Soviet Union. The South Vietnamese preferred a democracy like that of the United States (Spector 1).

The civil war began in 1955. North Vietnamese invaded South Vietnam, and in 1963 the United States sent troops to assist the South Vietnamese (Do 21). President Lyndon Johnson had recently been granted authority by Congress to use any means necessary to defend Americans and promote peace in Southeast Asia (Tonkin). Nine long years later, the United States signed the Paris Peace Accords, meant to bring an end to the war (Do 25). The United States agreed to remove troops. At the same time, the North and South Vietnamese were forced to release prisoners of war and withdraw troops from Laos and Cambodia (Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam). However, fighting continued for another two years. On the morning of April 30, 1975, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong took over Saigon, which housed the democratic South Vietnamese government, ending the war (Appendix B). They re-named the city Ho Chi Minh, and the North Vietnamese government reunified the country under its communist ideology, forcing many to leave the country (Spector 1, 6).

The Fall of Saigon was the final event that led several waves of South Vietnamese to immigrate to other countries. The United States launched a 24-hour evacuation of Saigon with hopes of getting all Americans out. The evacuation, called Operation Frequent Wind, consisted of helicopters shuttling South Vietnamese and Americans from Saigon to American vessels off the coast (Patterson 1). One of the American vessels that participated in the evacuation was the USS Kirk, captained by Paul Jacobs (USS). His ship was stationed in a defensive position close to shore and at first was ignored by helicopter pilots who were delivering evacuees to larger ships farther out at sea. Finally, after signaling for hours that they had an open flight deck, a Vietnamese helicopter landed on the Kirk. More helicopters followed, delivering Americans and South Vietnamese citizens until the Kirk’s small flight deck began to fill. Many of the helicopters with close-to-empty fuel tanks were pushed overboard to make room for the evacuees (The).

About 130,000 Americans and South Vietnamese, mainly government officials, were flown out of the country (Kibria 10). Many fled because of their disagreement with communist ideology or fear of being put into prison camps that held South Vietnamese POWs (Do 16). Caroline Nguyen Ticarro is a Vietnamese immigrant living in Minnesota, and her family was among those in Saigon who tried to board a helicopter on April 30th. Caroline recalls, “They were only taking women and children, and my Dad didn’t want to separate us” (Caroline’s Story). This was a problem many South Vietnamese encountered, and they were forced to explore other means of escape to keep their families together. Caroline, like many other immigrants, ended up escaping by boat.

To be free of communist rule, many South Vietnamese experienced risky weeklong boat journeys from Vietnam to refugee camps in other parts of Southeast Asia. Hung Duc Phung escaped Vietnam by boat and remembers cramming into a small boat about seven meters long (Phung). Escapees floated for days, overcrowded in small vessels with little food or water. Many waited to leave in August, during monsoon season, because the coast guard would not be out looking to send people back to Vietnam. “I remember one day when the storm died down, we passed by an area and they said, ‘Oh, we can let people up on the boat top.’ I saw some oily bubbles from the bottom of the sea. We knew right away we passed by a sinking boat” (Tran).

Pirates from Thailand were another obstacle the refugees encountered. A Los Angeles Times article from 1989 detailed an attack on a boat carrying over 140 South Vietnamese escapes. Pirates boarded the ship and demanded all valuables before setting it on fire. They raped women and left the refugees for dead. One man who made it out alive drifted at sea for several days using bloated corpses of other refugees for flotation (Wallace 1-25). Survivors estimate that as many as 50% of the refugees who fled by boat were killed by pirates (Do, 28).

After the Fall of Saigon, those who fled by boat traveled to refugee camps in Southeast Asia. One of the most important was in the Philippines, because for many, that was the last step before being sent to Europe, Australia, or the Americas. In the camps, South Vietnamese refugees took classes to explore the cultural differences they might encounter in the countries they hoped to emigrate to. A delegate of that country would interview them, and if the delegate thought resettlement to that country was the best option, they would be allowed to emigrate (Nguyen Ticarro).

Refugees from Vietnam came to the United States in three waves, and each had a different experience adapting to American society. The first wave was from 1975 to 1977 and consisted of over 130,000 people, mostly government and military officials, urban professionals, and well-educated English speakers familiar with American culture (Kelly 2). Many of these people left Vietnam right before the Fall of Saigon and did not encounter significant difficulties adapting to American culture (Promoting 12).

The second wave, from 1978 through the early 1980s, led to roughly half a million people coming to the United States (Kibria 11). Many South Vietnamese left because they feared that their way of life would not be the same with North Vietnamese in power (Kelly 16). People in this wave are referred to as “boat people” because they first fled by boat to refugee camps in Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Hong Kong. Many were soldiers, farmers, and fishermen who tended to be less educated. These refugees encountered more difficulties adjusting to American culture because they lacked the language skills and education to compete for higher paying jobs (Promoting 12).

The third wave of refugees arrived in the United States from the late 1980s through the 1990s. They consisted of those who had opposed the communist government and were recently released from re-education camps, as well as Amerasians, many of whom were children of United States soldiers and Vietnamese women (Phan 27-29). Around 75,000 Amerasians came to the United States after Congress passed the Amerasian Homecoming Act in 1987 (United). These “children of the dust” encountered racial discrimination in Vietnam and hoped to reunite with their fathers in America. Fewer than 3 percent found their fathers, and the U.S. government did little to nothing to help them search (Lamb).

Once given a visa, refugees exchanged their lives in Southeast Asian refugee camps for one of four camps in the United States: Camp Pendleton, California; Fort Chaffee, Arkansas; Eglin Air Force Base, Florida; and Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania. The camps were on military bases to accommodate large numbers of refugees waiting for sponsors who would help them integrate into American society. Nine relief organizations were contracted by the government to handle resettlement (Do 32, 34). Immigrants ended up in states all over the U.S., including Florida, California, Texas, and Minnesota (Rkasnuam) (Appendix C). Most immigrants who came Minnesota, like Caroline Nguyen Ticarro, were sponsored by Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services or Episcopal Migration Ministries. The Lutheran Social Services of Minnesota vision is that, “All people have the opportunity to live and work in community with dignity, safety, and hope” (About). These organizations were a major reason why Minnesota now has a large Vietnamese population and still attracts immigrants from around the world.

Minnesota had little racial or ethnic diversity until the mid 1970s. Settlers of English, Scottish, and Irish ancestry came this Midwestern state in the early 1800s. The first major immigrant wave at the end of the 19th century brought many Northern Europeans who boosted the logging and agriculture industries. A few decades later, Eastern Europeans found home in Minnesota. Census data from the Minnesota Demographic Center reveals that in 1860, 98 percent of the population was white. The South Vietnamese immigrants who fled after Fall of Saigon were the first to bring significant racial and ethnic diversity to the state, but since the late 1990s, Hmong, Somali, Indian, and Mexican immigrants have added to Minnesota’s newfound melting pot (Minnesota).

When South Vietnamese immigrants like Phuoc Tran came to Minnesota, they had to start their lives over. “Everything is new from languages, food, to how to interact with people” (Tran). Most who came in the first wave knew English, but refugees in the second and third waves encountered language challenges. Phuoc Tran immigrated when she was a young adult in the second wave. In Vietnam, she had attended law school and spoke both French and English. Because of her language skills she was able to go to college in Minnesota. Now she works as a librarian and an author. She had to start over in Minnesota and build a life from scratch.

The churches that sponsored the second wave of immigrants helped them explore new jobs, but because of language barriers, many had to settle for low-wage work. Kristina Doan is a first-generation Vietnamese-American whose father worked in the Vietnamese navy, but when he came to Minnesota, he ended up doing handyman work. He has had the same job for 30 years as a technician at Seagate Technology in Bloomington, Minnesota. She said, “It’s not that he wants to stay at the same job, it’s that he has the lack of language skills to get to places he wants to be” (Doan). His English has improved over the years, but at Seagate Technology, there are many other immigrants with whom he can converse in Vietnamese.

The process of assimilating led many immigrants to exchange their Vietnamese culture for American culture. They wanted to fit in and not be different. Some immigrants were afraid that if they told anyone they were Vietnamese, they would be ostracized because of the unpopular war. A 1975 Gallup Poll reported that 54% of Americans did not agree with the admittance of Vietnamese refugees (Do 29). Similar results were revealed in Harris Survey taken at the same time (Garofoli). Caroline Nguyen Ticarro was five when she immigrated to Minnesota and was told by her parents not to tell anyone she was Vietnamese. Caroline went through life telling people she was Hawaiian and admits, “I didn’t acknowledge my ‘Vietnamese-ism’ until I was 28” (Nguyen Ticarro). It was not until she thought about having her own family that she started to explore what it meant to be Vietnamese. Today, anti-immigrant sentiment like the Vietnamese experienced is still alive and challenging refugees from Syria as well as Muslims across the nation (Garofoli).

Language has become a problem for the Vietnamese immigrant community because English-speaking first-generation Vietnamese-Americans struggle to converse with their Vietnamese-speaking elders. Oral tradition is a large part of Vietnamese culture. However, many immigrants who had children encountered American teachers who urged them to exchange the Vietnamese language for English. Because of the language gap, history and oral tradition have been lost. In Minnesota, young Vietnamese activists are exploring the possibility of a Vietnamese language immersion school, which would help close the language gap between the elders and younger Vietnamese (Doan).

For Vietnamese immigrants and their families, food is one way to stay connected with Vietnam. For Caroline Nguyen Ticarro, “Having a pot of rice or always having fish sauce in the fridge was real and still is my instant connection to home” (Nguyen Ticarro). Kristina Doan, a young Vietnamese-American who grew up in Richfield, Minnesota, recalls family dinners of home cooked Vietnamese food. Kristina’s dad was adamant about the girls in her family learning how to cook traditional Vietnamese dishes, but growing up, Kristina and her sister were resistant. Now Kristina and her sister really want to learn to cook, so they can be reminded of their parents and Vietnamese culture.

First-generation Vietnamese-Americans in Minnesota, like Doan, have become advocates for the struggles of the Vietnamese community. “Within the Vietnamese organizer community we often compare ourselves to the Hmong” (Doan). Hmong immigrants came to Minnesota at around the same time that South Vietnamese immigrants did. They battled the spread of communism in Laos, and when it fell to communist rule, many chose to leave (“Hmong”). The Hmong people are well-organized politically.

“They are very politically involved and for as long as the Vietnamese community has been here, we have never had the opportunity to be or have had anyone be politically involved, so we are trying to gain visibility. Down at the capitol there’s a lot of us trying to get lawmakers to recognize that there are certain issues facing Southeast Asian communities and the Vietnamese community is part of this. We have established businesses here and our voices should be heard” (Doan).

Many first-generation Vietnamese activists are trying to get Vietnamese people to run for political office, but the older generation has been resistant. Kristina believes that because the war in Vietnam was so politically charged, many older immigrants want to stay out of the political system, but their first-generation Vietnamese children look for opportunities to get involved and advocate for the community.

The immigration of Vietnamese people has led to cultural exchange in Minnesota. Today more than 26,000 Vietnamese call Minnesota home (Our History). Many immigrants now own shops, businesses, and restaurants that contribute to the economy. Phuoc Tran says, “We get a lot of blessing from America and it is time for us to pay back” (Tran). Caroline Nguyen Ticarro recalls that when she first came to Minnesota, there was “a group of people that gathered once a year for Vietnamese New Year.” It was not until her mid-20s that she began to see streets of Vietnamese businesses and restaurants and realized that it had become part of the culture in Minnesota (Nguyen Ticarro).

Minnesota gave Vietnamese refugees a home, and through cultural exchanges it has become a welcoming place for immigrants from all over the world. As of 2011, the United States had admitted around 84,000 Somali refugees and close to 40% of them found their way to Minnesota (DeRusha). Caroline Nguyen Ticarro says, “I think that Minnesota again, because of their history and support for refugees, has become so diverse with Hmong, Somali, and people from other countries that it is all kind of intermixed now which is great” (Nguyen Ticarro). Immigrants from Somalia, Laos, and West African countries are now exploring new lives in Minnesota and making it an even richer and more ethnically diverse place. Despite this diversity and acceptance, immigrants to Minnesota encounter challenges as they try to assimilate into American society. Some of their challenges are similar to those the South Vietnamese faced, but with the growing xenophobic sentiment facing many of our newest immigrants today, their road to acceptance may be much more difficult.

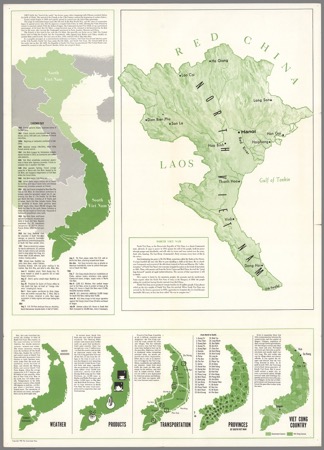

Appendix A

This map, from 1965, shows how Vietnam was divided before the Fall of Saigon. The dividing line was along the 17th parallel. Found in David Rumsey Historical Map Collection Cartography Associates and published by The Associated Press.

Appendix B

This is an example of a newspaper article describing the Fall of Saigon. It was published on May 1, 1975, the day after the North Vietnamese took over Saigon and the South Vietnamese government and military surrendered. From The New York Times.

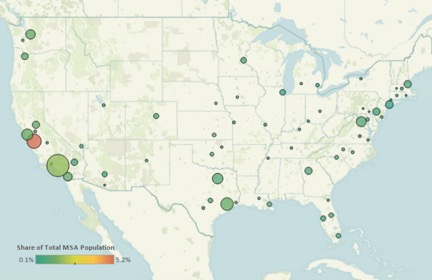

Appendix C

This is a map of the major metropolitan areas that Vietnamese immigrants

settled. The map shows data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau between

2008 and 2012. From Vietnamese Immigrants in the United States by the Migration Policy Institute.

Annotated Bibliography

Primary Sources

“About Lutheran Social Service of Minnesota (LSS).” About Lutheran Social Service of Minnesota (LSS). Lutheran Social Service of Minnesota, n.d. Web. 04 Apr. 2016.

This website is the website of one of the nine voluntary agencies that helped settle Vietnamese immigrants in Minnesota. I used this to quote their vision in my paper to show why they helped the Vietnamese refugees.

Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam, Paris, 27 January 1973. The Department of State Bulletin. Vol LXVIII. P. 169-188.

This was the legal document from the Paris Peace Accords. The Paris Peace Accords were signed to try and bring peace to Vietnam and were something I needed to talk about in my paper. I used this source to learn about what the conditions of the accords were, which later helped me think about how after they were signed there was a rapid destruction of the South Vietnamese powers.

Cao, Anh, Rep. “From Vietnamese Refugee to U.S. Representative.” CNN.com. CNN, 1 Apr. 2010. Web. 16 Jan. 2016.

This website detailed a true story of how a refugee from Vietnam became a U.S. Representative for Louisiana’s 2nd Congressional District. It was written by representative Anh Cao himself and allowed me to learn about what kinds of cultural challenges he faced when moving to, and growing up in, America.

Caroline’s Story. Prod. LiveWire Films. Catalyst Foundation. Catalyst Foundation, n.d. Web. 23 Jan. 2016.

This video was created to tell the story of Caroline Nguyen Ticarro. Caroline is Vietnamese and has her own nonprofit called Catalyst Foundation, which supports the Vietnamese-adopted community in Minnesota and on the East Coast, as well as rural disadvantaged communities in Vietnam. I used this to get a first-hand account of the journey to America for a Vietnamese refugee.

Doan, Kristina. Personal interview. 31 Jan. 2016.

Kristina is first-generation Vietnamese, and the daughter of two South Vietnamese immigrants who escaped Vietnam right after the Fall of Saigon. I conducted this interview to learn how Vietnamese culture has been integrated into Minnesotan culture, as well as how immigrants today are trying to create a balance between Vietnamese and Minnesotan/American culture.

Esper, George Esper. “Communists Take Over Saigon; U.S. Rescue Fleet Is Picking Up Vietnamese Who Fled in Boats.” New York Times [New York] 1 May 1975: n. pag. Print.

This is a news article published by the New York Times the day after the Fall of Saigon. I used this as an example of a first hand news report of the Fall of Saigon.

Garofoli, Joe. “America’s Long History of Shunning Refugees.” San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Corporation, 17 Nov. 2015. Web. 09 May 2016.

This website was about the long standing negative sentiment that immigrants who come to America face. It was mainly focused on Syrian refugees but I used this site because it mentioned opinion poll taken back in the 1970s regarding Vietnamese refugees. That poll detailed the American public’s feelings towards the refugees.

Hoang, Carina, ed. Boat People: Personal Stories from the Vietnamese Exodus. Cloverdale: Carina Hoang Communications, 2010. Print.

This book is a collection of first-hand accounts of escaping Vietnam by boat. I used this as a primary source to get a deeper understanding of the escape from Vietnam.

Nguyen Ticarro, Caroline. Personal interview. 30 Jan. 2016.

I conducted this interview to learn about coming to America and adjusting to American culture. Caroline was young when she first came to the United States and she had to adapt to a whole new culture. Caroline had great stories about her assimilation process which I later learned to be very common among other immigrants.

Nguyen-Tran, Thuy Duong. Vietnamese Community Oral History Project: Interview with Thùy Duong Nguyen-Tran. Interview by Simon Hoa Phan. Minnesota Historical Society. Minnesota Historical Society, 22 Oct. 2010. Web. 18 Jan. 2016.

This interview detailed what it was like to grow up as the child of Vietnamese immigrants. I used this to get a snapshot of Vietnamese culture and how it has changed due to American influence.

Phung, Hung Duc. Vietnamese Community Oral History Project: Interview with Hung Duc Phung. Interview by Simon-Hoa Phan. Minnesota Historical Society. Minnesota Historical Society, 22 Oct. 2010. Web. 23 Jan. 2016.

This interview told the story of Phung’s escape from Vietnam, life in a refugee camp, early life in Minnesota, and his life today in Minnesota. I used this to get a sense of what trying to start a new life in a new country was like for immigrants after they fled Vietnam.

“Place of Birth for the Foreign-Born Population in the United States.” Table. Minnesota State Demographic Center. Minnesota.gov, 2014. Web. 17 Jan. 2016.

This is a table created from the 2014 U.S. census and the 2014 Minnesota State census detailing the numbers of foreign-born people in both the U.S. and Minnesota. I used this to learn how many Vietnamese born citizens live in Minnesota.

Thai, Lisalan. Vietnamese Community Oral History Project: Interview with Lisalan Thai. Interview by Phuoc Thi Minh Tran. Minnesota Historical Society. Minnesota Historical Society, 22 Dec. 2010. Web. 25 Jan. 2016.

This interview was a first-hand account of coming to America and settling in Minnesota. I used this to learn about what it was like to leave your homeland and then live in a foreign setting with little knowledge of the country. I also used this interview to learn about how immigrants integrated western culture with their own Vietnamese culture and how they tried to create a balance between the two.

The Associated Press. Vietnam. Map. The Associated Press, 1965. David Rumsey Historical Map Collection Cartography Associates. Collection of David Rumsey. 8859001.jp2. Print.

This collection had a map that showed North and South Vietnam when they were two different countries. It also shows how Vietnam was split by the 17th parallel, and has some facts about the two different countries. I used this map to give the reader a visual on how Vietnam looked before the Fall of Saigon.

Tonkin Gulf Resolution; Public Law 88-408, 88th Congress, August 7, 1964; General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives.

This is the resolution passed by both the Senate and House of representatives that gave President Lyndon B. Johnson the authority to send as many troops and military support as he wanted to South Vietnam. I used this to learn about why the U.S. got so involved in the Vietnam War and how the U.S. never formally declared war on the North Vietnamese.

Tran, Phuoc Thi Minh. Videoconference interview. 28 Jan. 2016.

Phuoc escaped Vietnam by boat when she was a young adult. She spent 10 months in a refugee camp in the Philippines and then came to America. She was in law school in Vietnam but when she came to America she had to build a life for herself from scratch. I conducted this interview to get a first-hand account of escaping Vietnam, immigration to the United States, and then adapting to the culture and life in the America.

United States. Cong. House. Amerasian Homecoming Act. 100th. H. 3171. Washington: GPO, 1987. Print.

This is the piece of legislation known as the Amerasian Homecoming Act of 1987. It welcomed all Amerasians and their families to the U.S., and gave them a two year guaranteed stay. I used this to learn about the conditions of the Amerasian Homecoming Act and how it influenced who came during the third wave of immigration to the U.S. after the fall of Saigon.

Wallace, Charles P. “Nightmare at Sea: Sole Survivor Tells of Pirate Attack. “Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, 22 May 1989. Web. 08 Apr. 2016.

This news article was written about a man who was the only survivor in a brutal pirate attack. I used this article to further express how dangerous the boat journeys were.

Secondary Sources

“April 30, 1975: The Fall of Saigon.” Texas Tech University. Texas Tech University, 26 Mar. 2015. Web. 15 Jan. 2016.

This website is a digital exhibit on the fall of Saigon. It helped me gain background knowledge of the Vietnam War.

Adams, John S. “Minnesota.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, 2016. Web. 11 May 2016.

This website gave a summary of Minnesota from its inception to modern day. I used this to learn about what types of people settled in Minnesota back in the 1800s and then when it started to become more diverse and less white.

DeRusha, Jason. “Good Question: Why Did Somalis Locate Here?” WCCO CBS Minnesota. CBS Local Media, 19 Jan. 2011. Web. 28 Feb. 2016.

This website talked about why the Somali people came to Minnesota and how many live in Minnesota. I used this to help support the fact that Minnesota has become a hotspot for immigration. I took a statistic from this website to help support my claim.

Do, Hien Duc. The Vietnamese-Americans. Westport: Greenwood, 1999. Print.

This book covers how Vietnamese immigrants came to America and what struggles they had when arriving here. I used this to learn about how immigrants adapted to America and brought their cultures to America.

History.com Staff. “Paris Peace Accords Signed.” History.com. A+E Networks, 2009. Web. 16 Jan. 2016.

This website is about the Paris Peace Accords. I used this site to learn about how the signing of the accords affected the war, specifically the Fall of Saigon.

“Hmong.” Minnesota Historical Society. Minnesota Historical Society, n.d. Web. 26 Feb. 2016.

This website was about the Hmong Community in Minnesota. I used this to learn about why they came to Minnesota and how many live in Minnesota.

Kelly, Gail Paradise. Vietnam to America. Boulder: Westview, 1977. Print.

This book tells the story of how many immigrants found their way to America and all the steps in between. I used this to really understand in detail how the Vietnamese immigrants came to America.

Kibria, Nazli. Family Tightrope. Princeton: Princeton University, 1993. Print.

This book is about the social aspects of being a Vietnamese immigrant in America. I was able to learn about all the social challenges many immigrants faced when coming to America. I also took a statistic regarding how many people were flown out of Vietnam during Operation Frequent Wind.

Lam, Andrew. “Living in Two Cultures.” PBS American Experience. PBS, n.d. Web. 16 Jan. 2016.

This interview detailed what it was like to leave Vietnam and settle down in America. I used this to get a first hand account of how immigrants adjusted to new circumstances and how immigrants felt about America throughout the process of immigration.

Lamb, David. “Children of the Vietnam War.” History, Travel, Arts, Science, People, Places | Smithsonian. The Smithsonian, June 2009. Web. 14 May 2016.

This website was about the Amerasians, who were the children of American GI’s and Vietnamese women. I used this to learn about their struggles both in Vietnam and then coming to America to find their fathers.

Minnesota State Demographic Center. Minnesota Now, Then, When…. N.p.: Minnesota State Demographic Center, Apr. 2015. PDF.

This document was created for the Capitol Preservation Commission Subcommittee on Art, and it detailed the ethnic breakdown of the State from the beginning to their estimates for 2030. I used this to get some statistics of the ethnic diversity in Minnesota from the early 1800s al the way to 2015.

Nguyen, Diem. Vietnamese Immigrant Youth and Citizenship. Ed. Steven Gold and Rubén Rumbaut. El Paso: LFB Scholarly, 2012. Print. The New Americans: Recent Immigration and American Society.

This book examines what it is like to be a Vietnamese immigrant in America. I used this to learn about challenges immigrants face from a perspective other than that of an older person.

Our History. Vietnamese Social Services of Minnesota. Vietnamese Social Services of Minnesota, n.d. Web. 26 Jan. 2016.

This website talked about the reasons for the organization and a little history of why immigrants came to America. I used this because it talked about how immigrants that were part of the third wave came because they were political prisoners that were released from re-education camps run by the Communist government.

Patterson, Thom. “Enemy at the gate: The history-making, chaotic evacuation of Saigon.” CNN.com. N.p., 30 Apr. 2015. Web. 3 Feb. 2016.

This website was about Operation Frequent Wind. I used this to learn what Operation Frequent Wind was and when the big chaotic evacuation took place.

PBS. “People & Events: Ho Chi Minh.” PBS. PBS, n.d. Web. 08 May 2016.

This website gave a brief biography of Ho Chi Minh and detailed his achievements. I used this site to learn about his previous leadership before the Vietnam War.

Phan, Christian, Dr. “The Waves of Vietnamese Refugees and Immigrants to the United States.” Vietnamese-Americans. By Christian Phan. N.p.: Xulon Press, 2010. 27-29. Print.

This book had a section in it detailing the third wave of immigrants and why many of them came. I used this to understand who the third wave of immigrants were, and why they left Vietnam many years after the end of the war.

“Promoting Cultural Sensitivity.” CDC.gov. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d. Web. 16 Jan. 2016.

This publication detailed Vietnamese history and immigration to the United States, Vietnamese culture, the health of the Vietnamese in America and Vietnam, and common perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs about tuberculosis among the Vietnamese. I used this to gain knowledge of the different waves of immigrants over time.

Rkasnuam, Hataipreuk, and Jeanne Batalova. “Vietnamese Immigrants in the United States.” Migration Policy Institute. Migration Policy Institute, 25 Aug. 2014. Web. 16 Jan. 2016.

This website detailed the immigration of Vietnamese people over time and where they are now living. The Vietnamese immigration to America happened in three waves and this website has information about the third wave of immigrants which I used in my paper. This website also had a good visual map of the metropolitan areas that the Immigrants settled in. I used the map in my appendix.

Spector, Ronald. “Vietnam War.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica, 8 May 2015. Web. 15 Jan. 2016.

This website is about the Vietnam War. It covered the war from start to end and I used it to gain background knowledge on my topic.

THE USS KIRK FF-1087 ASSOCIATION. “Frequent Wind – USS Kirk FF-1087.”USS Kirk FF1087. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 July 2016.

This website detailed the USS Kirk’s missions and actions in Vietnam during the war. I used this source to learn about the role that the USS Kirk played during Operation Frequent Wind and more on how the evacuation worked.

USS Kirk: Leadership Amidst Chaos, A Legacy of Survival. Prod. Abigail Wiest.International Journal of Naval History. N.p., 21 July 2015. Web. 17 July 2016.

This documentary was published in the International Journal of Naval History and detailed the role of the USS Kirk in the Vietnam War. I used this documentary to learn how the USS Kirk helped with the escape efforts during Operation Frequent Wind.

“Voluntary Agencies.” Office of Refugee Resettlement. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 17 July 2012. Web. 6 Feb. 2016.

This website listed the voluntary agencies (VOLAGS) in America. I used this because when the Vietnamese refugees came to America, there were nine VOLAGS in America who were contracted by the government to oversee and helped to settle the refugees.

Yau, Jennifer. “The Foreign-Born Hmong in the United States.”Migrationpolicy.org. Migration Policy Institute, 01 Jan. 2005. Web. 12 May 2016.

This website detailed the Hmong immigration to the U.S. I used this to learn about when the Hmong people started to come to the U. S., and then to show in my paper how After the Vietnamese first made Minnesota more diverse and then the Hmong added on to that.

(Return to August 2016 Table of Contents)