By Hazel Sheeky Bird

Independent Scholar, Great Britain

At the beginning of the twentieth century, a great number of navalist books were produced for children in Britain and America. 1 Navalism, namely the belief that sea power is integral to a nation’s greatness and that naval preparedness is a country’s best and cheapest means of defense, found popular expression around the globe, in the years approaching the First World War. At heart, navalist discourses were national discourses and so countries that shared navalist principles, were actually set apart by them, often becoming competitors, if not outright enemies. Recently, the cultural impact of navalism, and naval competition on Britain and Germany has received scholarly attention, as has the structure, politics and organization of navalist organizations, such as the British Navy League and the Navy League of the United States. 2

To date, there has been no attempt to seriously gauge the impact of navalism on children’s early twentieth-century culture. It is now a truism to say that navalist organizations such as the Navy League overtly targeted children with propaganda. Mark Hamilton for example, writes that ‘the awakening and influencing of British youth’ was ‘an area of continual […] effort’ for the British Navy League. 3 Likewise, Armin Rappaport notes that the Navy League of the United States formed a Junior League in 1915. 4 However, current understanding of how these organizations promoted navalism to children is limited to a few references to the Navy League Map of the World, and the giving of lectures and lanternslides. Certainly in Britain, scholars have largely overlooked the impact of navalism on children’s wider culture.

Underpinning this paper is the belief that British and American navalists used writing for children, to foster their enthusiasm for the navy and to view themselves as belonging to great naval nations. Focusing on just one aspect of this significant body of material, it argues that British and American navalists used the figures of Horatio Nelson and John Paul Jones, respectively, to personify the idea of sea power and the principles of navalism. In Britain, Nelson was used to construct a national maritime narrative linked to service and sacrifice, and in the U.S., Jones was made to embody the idea of American sea power, which was aligned with American independence. When read through the lens of early-twentieth century Anglo-American relations, these children’s books demonstrate the way that navalists used writing for children as a vehicle for promoting competing national maritime ideologies. Consequently, children’s writing was instrumental in the development of the ‘special’ and often fractious relationship between the two countries.

In Britain, popular naval interest groups, such as the Navy League (formed in 1898), turned to writing for children to encourage high naval ideology. For the prolific Navy League propagandist Arnold White, children were an important audience for the League’s work, a fact that was acknowledged in Navy League publications. One leaflet stated that ‘if only the rising generation can be made to grasp the supreme fact of Sea Power, they could never, under any circumstances, contemplate any reduction of naval estimates, or countenance any step which would loosen, however slightly, our Command of the Sea. 5 Equally, the Imperial Maritime League (formed in 1909) also identified children as a key audience for navalist propaganda. Consequently, in January of 1909, it established a Junior Branch. This was a subscription-based club that cost members 1s. a year and which was open to anyone under the age of 21. The express purpose of the Junior Branch was to ‘arouse the interest’ of British youth in the Royal Navy and the Empire, to remind them that the English were ‘“sea dogs,” [and] that our Navy and our sailors have made us a great Sea Power, and that without our ships our country would be like a man who is blind and a cripple: he would do nothing and go nowhere’. 6

For both organizations, the life and career of Horatio Nelson, rehabilitated by Alfred Thayer Mahan’s two-volume work, The Life of Nelson (1897) and Sir John Knox Laughton’s Nelson (1985), proved to be a central means of personifying British Sea Power for children. 7 The connection between navalism, Nelson and childhood was certainly not limited to children’s writing. Thomas Davidson’s painting, England’s Pride and Glory (1894), depicts a young naval cadet gazing in admiration upon Lemuel Abbot’s earlier portrait of Nelson, which hung on the walls of the Naval Gallery at Greenwich (Figure 1). The painting captures the symbolic relationship that was forged at this time between young boys and Nelson and links them both to the idea of British Sea Power; the latter being alluded to through the scenes of naval battles that surround Nelson’s portrait.

Figure 1: Thomas Davidson, England’s Pride and Glory, 1894, oil on canvas 918 mm x 711 mm, (BHC 1811) National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

Davidson’s budding Nelson became a popular motif for writers seeking to encourage British boys to pursue a life of naval service. While the life of Nelson remained a popular subject in children’s writing, the fledgling Nelson proved to be a powerful persuasive tool for navalist children’s writers. In books such as The Sea Monarch (1912) and The Fritz Straffers (1918), Percy Westerman used the figure of the budding Nelson to create heroes that British boys could reasonably aspire to emulate. It was, after all, not every man’s destiny to be a great Admiral but every British boy could fulfill his birthright through service in the Royal Navy. 8

For British navalists, the real value of Nelson’s life and heroism did not come from his being a mythical figure but a human one, one whose greatness came from the example that he set of duty, efficiency and foresight. This emphasis on duty permeated not only texts that were specifically about Nelson but virtually all British maritime writing for children. Moreover it proved to be an extremely fluid and effective means of personifying a service ethos to British children, regardless of gender. This idea was particularly strong in the publications produced for children by the Junior Branch of the Imperial Maritime League. The monthly Junior Branch Leaflet featured an essay written on a naval or imperial hero, and over four separate issues, it detailed all aspects of Nelson’s career for its members. Mahan himself wrote Issue 23 (Figure 2) and he used his essay to reiterate the lessons that all children could learn from Nelson’s character, rather than his heroic deeds. Mahan told his readers that Nelson’s famous signal at the Battle of Trafalgar, ‘England Expects that Every Man Shall Do His Duty’, should not be taken as the singular expression of the moment but rather the guiding principle of his life and career. 9 This belief in the principles of duty, service and sacrifice, was at the core of British Edwardian navalism and it shaped British children’s maritime writing for the next 40 years.

Figure 2: ‘Admiral A. T. Mahan’, Junior Branch Leaflet, 23 (January 1911) in Volume of pamphlets and/or newspaper cuttings: Imperial Maritime League – Junior Branch, 1909-12, NMM HSM 16, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

If Nelson was made to embody the ideas of service and sacrifice on an individual level, the Royal Navy did so institutionally. British navalists projected an image of the Royal Navy as the arm of a benevolent maritime imperial power, one that worked tirelessly and selflessly to maintain peace around the world, protecting free trade and oppressed people. This construction was used to create a favorable impression of Britain and its navy, in comparison with competing naval nations; this, of course, applied to Germany, but it also included the United States.

British ambivalence toward the U.S. and its navy surfaced in British children’s naval stories, such as Gordon Stable’s 1902 invasion novel, The Cruise of the “Vengeful”. The novel recounts the planned invasion of Britain by a combined French and Russian force and sees Britain on the brink of defeat. Throughout Britain’s struggles America steadfastly maintains its neutrality, and Stables comments that the U.S. Navy was there only to protect American trade and that America was a ‘many headed hydra’, willing to extort high prices from Britain and take advantage of its vulnerability. 10 Thus British readers were encouraged to view the U.S. Navy as a means of ensuring American economic opportunism, in contrast to the Royal Navy that, so children were told, worked selflessly to maintain the balance of powers.

Other early-twentieth-century British writers were more circumspect in their comments but also intimated that the U.S. Navy was not fulfilling the role that might be expected of a major naval power – certainly, it was not fulfilling the role that Britain wished it would. Cecil Crofts’, Britain on and Beyond the Seas, (into its 6th edn. by 1911) was published by the Navy League and distributed to schoolchildren throughout Britain. The book recounts 400 years of Britain’s successes and failures at sea but it has surprisingly little to say about either the American Revolutionary War or the War of 1812. In fact, Croft’s entries on these conflicts focuses far more on the future possibilities of the U.S. Navy. So, following the briefest outline of the War of 1812, Croft observes of the U.S. that:

Recent events tend to prove that this great sister nation of the West is cementing these ties in a genuine and open-minded friendship with her natural ally, and that she is likely to take up in the future a larger share of the white man’s burden of attempting to raise the down trodden and oppressed even when they are some distance from her own shores. 11

Croft’s writing is an interesting exercise in projection as it reflects the way that some in Britain, sought to persuade the U.S. to use its navy to police the Pacific. This is evident in Croft’s hope that the U.S. will take a ‘larger share of the white man’s burden,’ – understandably such a view was likely to have been met with scepticism by many in the U.S., which had no intention of expanding its own navy in order for Britain to be free to protect its imperial interests. In his survey of Anglo-American naval relations, Arthur Marder points to Britain’s refusal at this time to see the U.S. as a potential enemy, writing that many in Britain thought, or hoped, that there was a natural racial affinity between the two nations, and that they were bound by blood and kinship. 12 Kathleen Burk also reiterates that some have seen something of a rapprochement forming between Britain and America by 1911. 13 Certainly this passage from Croft demonstrates the way that some British writers used writing for children to foster British citizens who would welcome closer Anglo-American naval relations.

The shape of American naval children’s writing at the turn of the century differed somewhat to that produced in Britain. In part, this was due to America’s ‘historic deep-seated revulsion’ toward a large standing navy, which forced American navalists to adopt different lines of argument. 14 The Navy League of the United States, formed in 1902, arguably faced more difficult challenges than the British. According to Armin Rappaport, not only was temper of the American people largely pacifist in the first decade of the twentieth century, but for many, a ‘two-ocean security complex’ rendered a large navy either redundant or irrelevant. 15 Although many British children’s books stressed the pacific role of the Royal Navy, Britain had been engaged in a naval arms race with Germany ever since the laying down of the German Naval Laws in 1898 and 1890. Moreover, for many Edwardian Britons, war was not only expected it was also welcomed. 16 British children’s books were therefore characterized by a combination of belligerence and benevolence. In America, however, navalists faced vehement and organized pacifist opposition, and so their work was shaped by the absolute necessity of avoiding accusations of war mongering and militarism. Thus, from around 1909, the Navy League of the United States began to actively use accounts of America’s past naval glories, to arouse enthusiasm for the navy by linking naval strength to American independence and neutrality.

Willis Boyd Allen’s Navy Blue: a story of cadet life in the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis (1898) indicates the way that writing for American children aligned the U.S. Navy, as an institution, with independence and peace. The book follows the career of two Annapolis cadets and the early portions of the novel depict Norman Holmes’ decision to join the navy, a decision that is inspired by a trip to Washington. Holmes is thrilled by John Trumbull’s painting Declaration of Independence (1817) which makes him feel ‘as never before, a grand pride in being himself an American’. 17 Added to this is the pride he feels on looking at the ‘Peace Monument’ dedicated ‘in memory of the Officers, Seamen and Marines of the United States Navy, who fell in defense of the union and liberation of the country, 1861-1865.’ In a passage that speaks directly to pacifist criticisms of American navalism, Allen has Holmes realize that ‘America was not at war with any nation. Secure within her own borders, firm in the maintenance of honorable dignity’ and that her ‘hands stretched forth to succor the helpless, to feed the hungry, to clothe the destitute, her voice was ever for peace on earth, good-will toward men. […] He would be, not a warrior, unless she should call her children to arms, but a patriot of peace.’

While Allen stressed the peacekeeping nature of the modern U.S. Navy, other writers drew upon the naval past to illustrate the need for a strong, defensive navy. Willis John Abbot’s The Story of Our Navy for Young Americans (1910), is typical of American texts, that used the figure of John Paul Jones to advocate a large standing navy, to argue that naval defence was integral to America’s historic rejection of British tyranny and, ultimately, to personify the principle of independence for children. Abbot begins his book with a detailed and emotive depiction of the practice of impressment, which is used to illustrate both the tyrannical actions of the Royal Navy and the nation that it symbolises. He asks his readers to imagine a crew back from a long weary voyage, almost in sight of loved ones waiting for them on shore, who are kidnapped by a British man-of-war and made ‘subject to the will of a blue-coated tyrant’. 18 Abbot in fact refers directly to impressed sailors as being kidnapped by the Royal Navy and presents their actions and attitude towards Americans as oppressive and arrogant. He stresses a deep sense of American hatred for Britain, and particularly its navy, in the years before both the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. The Royal Navy is not only depicted as being tyrannical toward Americans but it is also presented as a brutal institution. This was a popular theme in American naval writing for children. William O. Stevens, for example, made this point in his 1914 book, The Story of Our Navy. Like Abbot, he refers to impressed men as living a life of slavery. 19 It is perhaps unsurprising that British texts make no mention of impressments.

In American writing for children, the use of John Paul Jones bears resemblance to that of Nelson in Britain. A book like Abbot’s demonstrates the way that Jones’ life was used to inspire readers, not necessarily to serve in the U.S. Navy but to value the principle of liberty – a principle that Jones was made to represent. This point was conveyed by the connection that was repeatedly emphasized between Jones and the American flag. In his 1907 book, Heroes of the Navy in America (Figure 3), Charles Morris linked Jones to the first American flag, made of ‘yellow silk, bearing the picture of a pine tree with a rattle snake coiled at its root, and [bearing] the motto “Don’t tread on me”. 20

Figure 3: Front cover, Charles Morris, Heroes of the Navy in America (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1907).

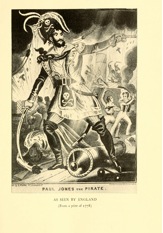

Similarly, he recounts that it was Jones who was first to hoist the Stars and Stripes onboard a ship of the U.S. Navy. Abbot also stresses this connection and the result is sense of shared symbolism whereby Jones embodies American independence almost as much as the flag. Where Nelson was made to embody duty, efficiency and foresight, Jones was most often associated with boldness, a deep love of America, consummate skill as a sailor and an absolute refusal to be cowed by Britain. This final point is stressed repeatedly in Abbot’s descriptions of Jones’ actions on the coast of Britain during the American Revolution. Abbot writes that ‘Paul Jones showed Great Britain that her boasted power was a bubble. He ravaged the seas within cannon-shot of English headlands. He captured and burned merchantmen, drove the rates of insurance up to panic prices, paralyzed British shipping-trade, and even made small incursions into British territory’. 21 He also refers to Jones having ‘alarmed all England’ and for bringing home the realties of war to ‘the people of the tight little island’. For Abbot, Britain’s unwillingness to acknowledge Jones as an American naval officer, branding him instead as a pirate, revealed its refusal to recognise the legitimacy of American independence (Figure 4).

Figure 4: ‘Paul Jones the Pirate as Seen by England’, Illustrative plate in Willis John Abbot, The Story of Our Navy for Young Americans, from Colonial Days to the Present Time (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1910), facing page 12.

It is difficult to say with certainty that the presence of navalist arguments in writing for children was always the result of orchestrated efforts to inculcate this ideology in its readers. Edwardian Britain has been described as a particularly ‘navy-conscious’ nation, so the strong presence of navalist discourses in British children’s writing could reasonably be ascribed to ‘passive ideology’. 22 Clearly, more work is needed to fully explore the connections between children’s writers and navalist organizations, if firmer conclusions are to be drawn. What is clear from this small survey of writing for children is that while British naval writers by 1910 sought to underplay historic antagonism between the two countries, American writers often emphasised it. There is a sense of revelry to Abbot’s writing that suggests a celebration of Jones’ victories over the British in the present moment and not only in the past. Moreover, while America continued to view Britain with hostility and suspicion, Britain, of necessity, viewed the U.S. as a ‘sister’ nation. Children’s naval books played an important role in the construction of this relationship, providing a cultural arena whereby British and American navalists could fight for the command of the seas, in the same way that naval theatres allowed Britain and Germany to compete in the years leading up to the First World War. 23 In children’s books historic naval battles could be fought anew, old rivalries and wounds explored and re-opened, and truces and treaties re-forged. In doing so, they shaped British and American children’s views of their future allies and prepared them for the roles that they and their countries would play in the coming decades.

(Return to the July 2014 Issue Table of Contents)

—————————————————-

- At present no substantial bibliographical source exists for British or American children’s navalist texts, and it is partly the aim of my ongoing research to form one. The balance of this article, as a result of my current research, perhaps leans towards British texts. Indicative titles about the history of the U.S. Navy, recommended to children would include, Cyrus T. Brady (himself a graduate of Annapolis), The Freedom of the Seas: A Romance of the War of 1812 (1899), James Barnes (born in Annapolis) Naval Actions of the War of 1812 (1896) and Benson J. Lossing, The Story of the United States Navy for Boys (1881); books about the Navy and its ships included F. E. Evans, The Marvel Book of American Ships (1917), Frederic Stanhope Hill, The Romance of the American Navy (1910); fictional series included Frank Gee Patchin’s Battleship Boys novels (1910-1918) and the historical Navy Boys series, including the novel The Navy Boys’ Cruise with John Paul Jones (1899; 1912). ↩

- On the cultural and competitive nature of British and German navalism see Jan Rüger, The Great Naval Game. Britain and Germany in the Age of Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006); on role of British navalism in the development of imperial ideology see Andrew S. Thompson, Imperial Britain: the Empire in British politics, c. 1880- 1932 (Essex: Pearson 2000), 44-50; on the political construction of the British Navy League see Matthew Johnson, “The Liberal Party and the Navy League in Britain before the Great War”, Twentieth Century British History 22 2 (2010): 137-163. ↩

- Mark Hamilton, “The New Navalism and the British Navy League 1895-1914”, Mariner’s Mirror 64 (1978): 37-44 (42). ↩

- Armin Rappaport, The Navy League of the United States (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1962), 49. ↩

- ‘What is the Navy League? The Aims and Purposes of the Organisation’, 2. In ‘My History of the Navy League’, NMM/WHI/142, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. Quoted with permission from Woburn Abbey. ↩

- Junior Branch, First Annual Report, 1st January 1909- 31st December 1909, 1 and Untitled Leaflet, c. 1909, unpaginated, in Volume of pamphlets and/or newspaper cuttings: Imperial Maritime League – Junior Branch, 1909-12, NMM HSM 16, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. ↩

- On the rehabilitation of Nelson’s reputation see, Andrew Lambert, The Foundation of Naval History. John Knox Laughton, the Royal Navy and the Historical Profession (London: Chatham Publishing, 1998). ↩

- The Fritz Staffers was republished in 1931 as The Keepers of the Narrow Seas A Story of the Great War (London: S. W. Partridge & Co, 1931). ↩

- Many thanks to the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich for allowing me to use my own photograph in this article (Figure 2), which I initially took just for research purposes. ↩

- Gordon Stables, The Cruise of the “Vengeful” A Story of the Royal Navy (1902; London: Dean & Son, Ltd., 1936), 225. ↩

- Cecil, H. Crofts, Britain On and Beyond the Sea; being a handbook to the navy league map of the world, 6th ed. (Edinburgh and London: Johnston Ltd., 1911), 50. ↩

- Arthur Marder, Anatomy of British Sea Power. A History of British Naval policy in the Pre-Dreadnought Era, 1880-1905 (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1940), 443. ↩

- Kathleen Burk, Old World New World, Great Britain and America from the Beginning (New York: Atlantic, 2008), 299. ↩

- Rappaport, The Navy League of the United States, 23. See also William P. Leeman, The Long Road to Annapolis. The Founding of the Naval Academy and the Emerging American Republic (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 20. ↩

- Rappaport, The Navy League of the United States, 8, 14, 23. ↩

- On the Anglo-German naval arms race see Arthur J. Marder, From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow. The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era, 1904 – 1919, vol. 1, The Road to War, 1904-1914 (London: Oxford University Press, 1961). ↩

- Willis Boyd Allen, Navy Blue: a story of cadet life in the United States naval Academy at Annapolis (New York: E. P Dutton & Co., 1898), 12,14. ↩

- Willis John Abbot, The Story of Our Navy For Young Americans. From Colonial Days to the Present Time (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1910), 3. ↩

- William O. Stevens, The Story of Our Navy (New York and London: Harper, 1914), 54. ↩

- Charles Morris, Heroes of the Navy in America (Philadelphia and London: Lippincott, 1907), 22-23. ↩

- Abbot, The Story of Our Navy For Young Americans, 13. ↩

- Thompson, Imperial Britain, 45; Peter Hollindale classifies two main types of ideology in children’s literature; ‘intended surface ideology’ is defined as the ‘explicit, social, political or moral beliefs of the individual writers and his wish to recommend them to children through the story’ and passive ideology as the writer’s ‘unexamined assumptions’. Peter Hollingdale, Ideology and the Children’s Book (1988; Oxford: The Thimble Press, 1994), 10. ↩

- On the cultural naval competition between Britain and Germany, prior to 1914, see Rüger, The Great Naval Game, 206-242. ↩

One Response to Naval History and Heroes: The Influence of U.S. and British Navalism on Children’s Writing, 1895-1914