Aleksandr Gelfand

Archives and Records Management Section (ARMS)

The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations.

The archives of the United Nations covers four broad areas: the Secretaries-General, Secretariat Departments, Peacekeeping Missions, and Predecessor Organizations. The archives are arranged into Series which fall under larger archival groups (or “Fonds”) that are derived from the particular office or agency that created them. The creating agency can be a United Nations department, mission, panel or body, Secretary-General, or other United Nations functional unit.

I am proud to highlight the archive’s collection of materials related to one predecessor organization, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration – UNRRA. UNRRA’s mandate ended in 1947 and it was liquidated in 1948. Its records, at the time estimated to number more than 50 million pages, were transferred to the newly established United Nations in New York. Today, more than 3,000 linear feet of its records, including approximately 10,000 photographs are available for research. These include files dealing with supply, procurement, and shipping operations, as well as repatriation and care of displaced persons stranded around the world, and the efforts to draft and administer the 1944 International Sanitary Conventions.

On March 12, 1945, a ship sailed from the United States for Europe carrying relief supplies destined for Poland. It was one of the first chartered by the United Nations Relief and Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and would soon turn into a flood of ships, which carried the majority of the more than 24 million tons of supplies sent by UNRRA to 17 receiving countries.

Founded in November 1943 by 44 allied states (popularly styled the “United Nations”), the main tasks of the organization were to provide assistance to members who had been invaded by the Axis powers. Aid took the form of food and clothing; assistance in the resumption of urgently needed agricultural and industrial production, as well as other essential services; and help in the repatriation of displaced persons (DPs).

With missions and procurement offices in 42 countries, purchased or donated material was soon arriving in ports throughout North and South America, Africa, Asia, Europe, and Australia. To handle the largest relief operation up to that point in history, UNRRA grew to eventually encompass almost 25,000 staff members supported by a massive logistics infrastructure.

The millionth ton of UNRRA foodstuffs unloaded in China from the freighter Paul David Jones, which carried wheat from the US to Shanghai (S-0801-0001-11-00029, UN Archives)

Once requested supplies reached the port of departure, UNRRA would officially take responsibility, which would only be relinquished once they reached their port of delivery. Early on, a decision had been made to employ private firms for the various aspects of shipping operations, with ships mainly chartered on a single trip basis. Some cargo, however, required special accommodation. As part of agricultural rehabilitation, UNRRA shipped thousands of animals to Europe and Asia, requiring specially configured vessels. Following an agreement with the War Shipping Administration (WSA), 71 ships, mostly Victory and Liberty types built en masse by the United States during the war, were converted for that purpose. Transportation of trains required additional specialized vessels, which were found in brand new Norwegian Belships. One such ship carried 48 completely erected locomotives and 48 tenders in a single UNRRA chartered voyage.

[Left] UNRRA mules, hoisted on board in pairs, start their voyage to Greece to replace draft animals lost in the war (S-0800-0003-0001-00028, UN Archives); [Right] Norwegian train ship SS Beljeanne (S-0801-0011-0001-00030, UN Archives)

The delivery process was anything but smooth sailing. Many of the destination ports in Europe and Asia were left devastated by the war, making unloading a great problem, forcing ships to dock in much more distant harbors. Some ports, such as those in Albania could not accommodate the large ships used, forcing a transit stop in Italy, where the supplies were reloaded onto smaller vessels. Multiple representatives of receiving nations in ports, such as Trieste, were on site to take custody of the cargo and ensure that no pilfering occurred as the supplies were unloaded and sent onwards to their final destinations. For landlocked countries, such as Czechoslovakia, this was an especially pertinent problem: its relief supplies had to travel from 15 different ports, which were under 11 different sovereignties.

The emergency on the ground meant that supplies had to be shipped quickly, with multiple ships en route or being loaded at any given time. In Italy, at the height of the program, an UNRRA campaign touted that three ships were arriving daily. The speed and volume with which the material was delivered sometimes created backlogs at destination ports, forcing UNRRA to scramble to divert supplies elsewhere, acquire warehouse facilities, and delay sailings. One such incident happened in China in July 1946, when 15 ships already en route and 17 more scheduled to sail the same month had to be rerouted and delayed.

“Tre navi al giorno” – “Three ships a day” – display symbolizing international character of UNRRA shipments to Italy (S-0800-0003-0009-00010, UN Archives)

Since sailings had to be undertaken year-round, at times weather was less than cooperative. In early 1947, the Baltic Sea froze as 5,000 horses from the United States were on their way to Poland. One of the vessels became icebound and others were forced to divert. By the time they were able to make it to their final destination, losses for each vessel ranged from 5-to-25 percent. However, the overall losses of livestock shipments of the entire program ultimately amounted to only 3.8 percent.

As port facilities were repaired and expanded, most of the cargo made it to its destination on time and in good condition. For the first eight months of 1946, UNRRA was the largest single exporter in the world, with more than one million gross long tons shipped each month from the Western Hemisphere.

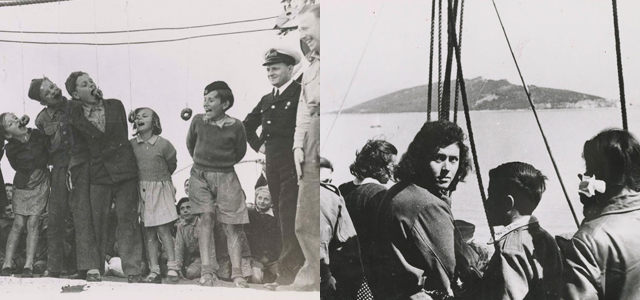

Relief supplies were not the only cargo carried by UNRRA chartered ships. World War II had created millions of refugees who now had to be aided in their return. Although the majority were repatriated via trains and other ground transportation, tens of thousands had to be transported by seaborn vessels. The shortest and easiest voyages involved displaced persons housed in UNRRA run DP camps in the Middle East and entailed a relatively short trip via the Mediterranean Sea.

[Left] A game organized for DP children on deck during the trip from El Shatt Camp to Yugoslavia (S-0800-0010-0015-0034, UN Archives); [Right] Yugoslav refugees see their homeland from aboard a ship (S-0800-0010-0015-0038, UN Archives)

Longer trips proved far more complicated and involved multiple layovers. Logistics for Greek DPs in Africa, Jewish refugees from Austria in China, Polish DPs in India, Mexico, Iran, and New Zealand, as well as multiple other nationalities, had to be organized and coordinated at a time of a general shortage of passenger shipping. The multiyear process was still in progress when the responsibility for DPs was transferred from UNRRA to the newly established International Refugee Organization (IRO) in 1947.

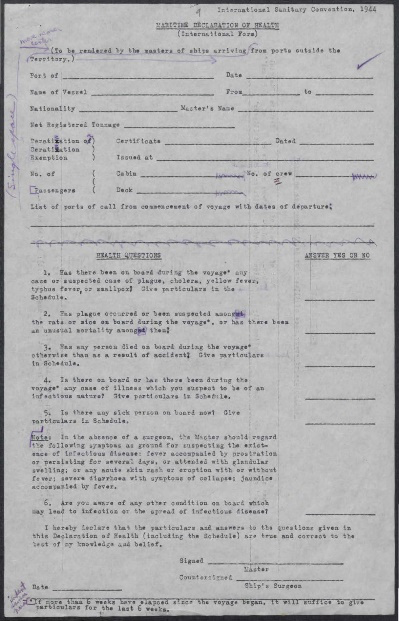

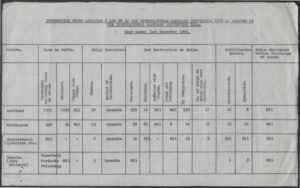

In additional to being a major client of the shipping industry, UNRRA had a considerable critical impact on maritime sanitation policies and procedures when it was tasked with drafting revised International Sanitary Conventions in 1944. When the Conventions were adopted the next year, UNRRA became their administrator, serving as a point of contact for all member states. Among the changes that the Conventions brought about were, standardizing an international form of certificate of inoculation for travel by sea, land, and air; increasing the distance at which certain ships had to be moored from the shore; and stipulating the quarantine measures for persons without a valid inoculation certificate. UNRRA administered the Conventions until the creation of the World Health Organization (WHO), which inherited that role in 1948.

Maritime health information provided to UNRRA by New Zealand UNRRA (S-1271-0000-0069-1, UN Archives)

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the United Nations Archives and Records Management Section, has made over 800,000 digitized pages of UNRRA records available. They can all be viewed online via the Archives’ catalog.

(Return to December 2022 Table of Contents)