Contents:

Introduction

Nigerian Navy on the Eve of the Nigerian Civil War

The Battle for Nigeria’s Coastal Areas: Operational Responsibility and the Development of the Nigerian Navy

Contribution of the Navy to the Defeat of Biafra

Dr. William Abiodun Duyile

Ekiti State University

Introduction

The principal actors in the Nigerian Civil War can be referred to as the Federal Government of Nigeria under the leadership of Major General Yakubu Gowon on the part of Nigeria. The Biafra side was headed by Lt Colonel Odumegwu Emeka Ojukwu. Although the Organisation of Africa Unity (OAU) now renamed the African Union (AU) was solidly behind the Federal government, yet, four African states; Tanzania, Gabon, Ivory Coast and Zambia recognized Ojukwu’s regime in 1968.

No European country actually accorded diplomatic recognition to Ojukwu’s regime, yet many of them were sympathetic to Biafra. This was as a result of well- tailored propaganda which he skilfully fed the European and United States of America press. On the side of the Federal Government of Nigeria, only Britain under the Labour Prime Minister, Mr Harold Wilson, supported the stand of the Federal military government openly. Opinion was divided in the British House of Commons as to whether the country’s Labour government should stop British arms delivery to Nigeria. Harold Wilson showed much political courage in resisting this pressure. Many European countries refused to sell arms to Nigeria for cash payment. Some foreign church organizations and gunrunners were also enthusiastic in defiling the Federal Military Governments blockade of the Biafra region.

It is in this circumstance that the significance of the Nigeria Navy to the victory of Federal military forces should be examined and understood. The Navy has as its primary responsibility the protection of Nigeria’s territorial sea, especially the maritime flank of the country, from sea-borne attack. The Navy’s duty of supporting the other arms of the military to prosecute the civil war was also important and core to the defeat of Biafra. Nigeria is a coastal state; hence in most wars such as the Nigerian Civil War there must be some kind of a coastal operation to aid the overall maritime strategy and capability of the military operations on land, sea and air.

Nigerian Navy on the Eve of the Nigerian Civil War

Before the Nigerian Civil War, the Nigerian Navy had acquired a considerable number of platforms either by new construction or by transfer of old ships from the United States, Great Britain, the Netherlands, Germany, and France. Nigeria’s only frigate, NNS Nigeria, was constructed in the Netherlands in 1965. Many ships owned by the Nigerian Navy originally belonged to either a European nation or the United States. Nigeria, with its ambition of developing a sea-going naval force, had refrained from acquiring only older vessels, but rather followed a pattern of buying newly constructed ships from the naval dockyards of Europe and the United States. 1

Foreign technical expertise was readily provided by the British before the Nigerian Civil War, and the Russians during the war, covering planning and execution of maintenance activities. 2 The Nigerian Navy before the civil war had no doubt desired to protect their maritime interests and this was by way of policy articulation, legal reforms, strategic reviews and, most importantly, by its blockade of the maritime environment. This was why the Nigerian Navy had during the war embarked on denying the enemy the sea lines of communication. Yet, at the same time, the Navy was able to safeguard and dominate the sea to support the overall strategy of the Nigerian military during the conflict.

Foreign technical expertise was readily provided by the British before the Nigerian Civil War, and the Russians during the war, covering planning and execution of maintenance activities. 2 The Nigerian Navy before the civil war had no doubt desired to protect their maritime interests and this was by way of policy articulation, legal reforms, strategic reviews and, most importantly, by its blockade of the maritime environment. This was why the Nigerian Navy had during the war embarked on denying the enemy the sea lines of communication. Yet, at the same time, the Navy was able to safeguard and dominate the sea to support the overall strategy of the Nigerian military during the conflict.

Before the first shot was fired during the Nigerian Civil War, the Nigerian Navy had already been called to duty. 3 The Navy was ordered to carry out a blockade of Port Harcourt and the Bonny littoral space, thereby denying the Biafra Republic free access to and use of their harbours. 4 The blockade was introduced by the Federal military government to stop ships from anchoring at the two Biafra ports. 5 Although Nigeria did not have the naval capability to enforce it, foreign nations, especially African states, respected the policy because Nigeria was the diplomatically recognised state in the conflict. 6 This meant twenty-four hour patrols of the eastern waters. In the month of June, blockade of the sea was made tighter by the Nigerian Navy. 7 By the early part of July, no ships were allowed even to the oil terminal for loading. It was to safeguard the oil terminal that the Gowon administration decided to seize and place Bonny under the control of the federal government on July 26, 1967. 8 For this reason a division was created from the Lagos Garrison Organisation and named the Third Marine Commando. 9

During this period, the ships were few and unsophisticated and, apart from this, they were refitted abroad. However, second level maintenance was properly planned and executed by well-trained technical personnel using maintenance facilities and spares provided. 10 As expected, maintenance and availability of ships throughout this period under foreign technical management was good as evident in the successful use of the vessels to prosecute assigned tasks in the Nigerian Civil War.

The declaration of Biafra independence on May 30, 1967, led to the Nigerian Navy losing some of its experienced officers of Igbo stock to Biafra and even a ship, NNS Ibadan, which was seized by Biafra through the connivance of its commanding officer, Lt. Cdr.Anuku. Also, in Lagos, the behaviour of Igbo officers before April 18 at the naval base was beginning to suggest that all was not well within the naval force. In order to forestall unforeseen incidents in the barracks, especially when reports indicated that some officers were already illegally in possession of arms, all officers present in Lagos were summoned to the base and addressed by the Chief of Naval Staff, Commodore Wey, on 18 April 1967. 11 Thereafter, all officers’ quarters in the barracks were searched. Two officers were caught with sub-machine guns in their residence. 2 However, nothing was found in the naval ratings’(rank and file) accommodation at the base.

By this time the Igbo officers and men had become aware that special security attention was being paid to them. Information was also received that certain Igbo officers and ratings were planning to abscond from Lagos and most eventually did, ship security was then tightened in Lagos. 13 However, when work resumed on 24 April 1967, sabotage was reported on most of the sensitive electrical and electronic equipment of almost all the ships. 11 In the flagship, the main armament had been rendered useless and thirty Igbo ratings had absconded. 2 The security of ships with Biafra ratings and officers was becoming very difficult to manage for the naval authorities. 2 It was therefore decided that Igbo officers and ratings be drafted to NNS Beecroft before they damaged the equipment inside the ships. 17

Aside from the fact that Nigeria lost some of its experienced officers to Biafra just at the onset of the war, Biafra also held sway in terms of economic reserve judging from the fact that the old Eastern Region {Biafra}had a large chunk of Nigeria’s petroleum produce. Conversely, the Nigerian military garrisons and ammunitions were situated outside the Eastern Region. However, Ojukwu was convinced that without the support of the big powers Yakubu Gowon’s regime lacked the needed organisation, strategy, and military competence to restrain Eastern Nigeria from seceding. 18 Given that the United States and Britain were allies, especially as the Cold War put them on one side of the divide against communism, it was supposed that Nigeria and Biafra needed support from the powers to give them an impetus over each other.

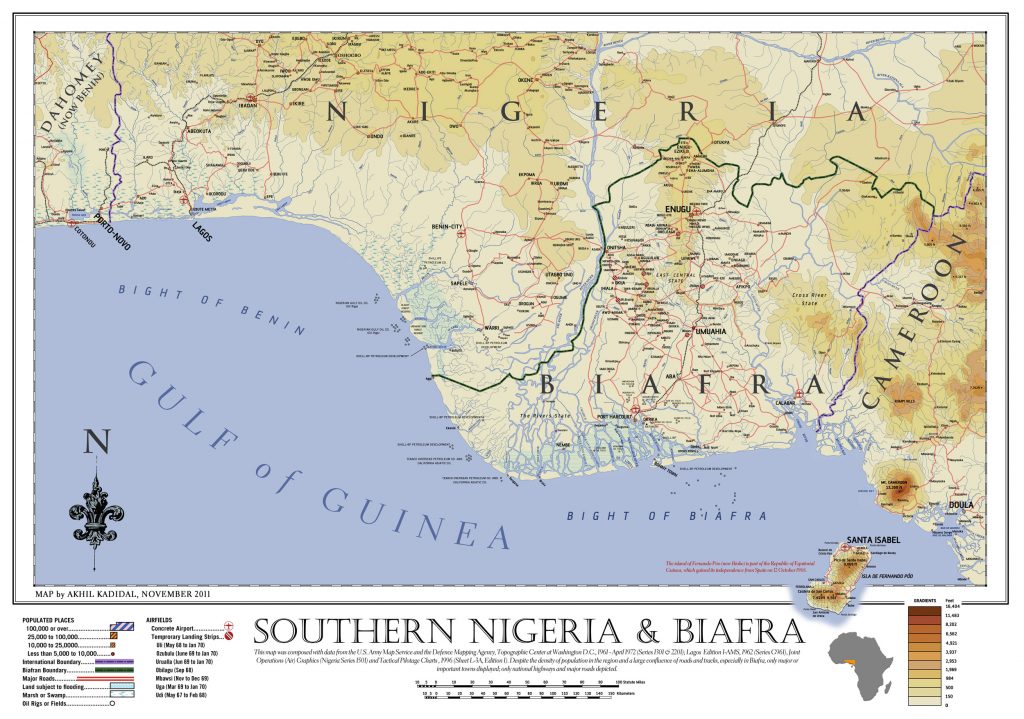

The declaration of a state of emergency and the creation of twelve states on 27 May 1967 by Gowon changed the structure of the nation. By announcing the dissolution of the regional structure and the creation of the twelve states, the federal government divided the Eastern Region into three states; East Central State, South Eastern State, and Rivers State. 19 The split meant that Ojukwu was left with a third of the area hitherto under his control, which became East Central State, and it was exclusively an Igbo state. 2 The state creation separated non-Igbo ethnic groups from the Igbo in an attempt to galvanize their support for the federal government. However, most of the oil producing parts of Igbo land were severed from Ojukwu’s control and placed in Rivers State. 21 Furthermore, the bulk of the oil revenue came from the two other states, which had been excised from the Eastern Region. In strategic terms, the land that belonged to Ojukwu had become encircled by other states that were inhabited by non-Igbos. Ojukwu saw the action as an attempt to dismember the Eastern Region and deprive it of its revenue, unity, access to the sea, and denying it of the border to Cameroon. 22 Colonel Ojukwu’s reply to General Gowon was to declare secession on the 30 May 1967. This action triggered the Nigerian Civil War on 6 July 1967.

The Battle for Nigeria’s Coastal Areas: Operational Responsibility and the Development of the Nigerian Navy

War commenced on July 6, first as the so called ‘police action’, which entailed a three-pronged assault (from Obudu, Garkem and Nsukka). 23 Prior to that time there had been skirmishes along the borders between Nigerian and Biafra reconnaissance teams; although originally maintaining that its response amounted to ‘police action’, what was later enacted on the ground by Nigerian forces was maximum intensity offensive. 24

During the civil war, NNS Ogoja led all nine coastal operations from Lagos to the coastal areas of Biafra. There was NNS Nigeria (a frigate) which was the flagship; it was too big for such coastal waters as the entrance from Port Harcourt to Bonny. It would have been too risky to assign NNS Nigeria for such coastal operations within the Nigerian waterways; as such, it was used as a guide up to the fairway buoy in the entrance of Bonny. 25 NNS Nigeria was behind other ships during the attack on land and gave support to the bombardment of land targets in Bonny, Port Harcourt, Peterside, and Calabar among others. 2 NNS Ogoja was the ship that led the naval fleet in the military operation to storm Biafra from the sea, partly to enforce a blockade of the rebel republic and purposely to land troops of the Third Marine Commando, commanded by Lt. Colonel Benjamin Adekunle at Bonny on 26 July 1967. 27 The Navy’s assignment was to liberate Port Harcourt, Calabar, Warri, and other coastal states. NNS Ogoja functioned in an assault capacity followed by NNS Lokoja carrying the troops and their ordnance for a landing, later described as one of the best operational assignments by any of the navies in the world. 28 The ships that took part in the coastal operations in Bonny were: NNS Nigeria, the flagship under the command of Captain Soroh; NNS Penelope, under the command of Commander James Rawe, which was the Nigerian Navy scout ship; NNS Lokoja, a landing ship, under the command of Lt. Cdr. A. Joe; NNS Ogoja was under the command of Lt. Cdr. Akin Aduwo; NNS Benin was under the command of Lt. Fingesi; NNS Enugu was under the command of Lt. A. Abdullahi; MV Bode Thomas was under the command of Captain Laniyan, Merchant Ship and Logistic Ship, Nigerian Port Authority; MV King Jaja was a Merchant Ship and Logistic Ship belonging to the Nigerian Port Authority. 29 There was also the Army’s 3rd Marine Commando Division consisting of elements of the Lagos Garrison Organisation and a recently trained battalion comprising newly recruited men from littoral towns and cities such as Rivers and Cross River. 2 This battalion had just been raised with intensive training at Bonny Camp, Victoria Island, Lagos. The division was under the command of Lt. Col. Benjamin Adekunle. 27

At the Bonny jetty, the landing went on without hitches for the Nigerian troops. Unfortunately, Biafra naval forces on NNS Ibadan, a vessel seized at the Calabar naval base immediately after the declaration of Biafra, had sighted the Nigerian troops landing ashore. 32 A few kilometres from Bonny and Peterside, the town opposite Bonny, the first battle to control the sea began. The Nigerian Navy through NNS Ogoja was able to incapacitate the seized ship now owned by Biafra. The Biafra commanding officer beached the ship at Boiler Point and escaped with his surviving men into the mangrove swamp. 25 With the neutralisation of NNS Ibadan, the Biafra Navy was no longer a threat to the Nigerian Navy. The Biafra forces however attacked Bonny again after sending aircraft to bomb the ships on patrol in Bonny and the oil tank farms. 34 The Nigerian Navy was able to safeguard this oil terminal and the aircraft were repelled by naval ships through its Anti Air Warfare(AAW) ammunitions, without causing any damage to them. 2 The Navy, however, continued to maintain its presence in Bonny by detailing duty ships to keep constant guard and patrol of the Bonny channel. 36 The Navy also continued to supply materials to Bonny Island with merchant ships and NNS Lokoja. 37 The naval amphibious task force captured the ocean oil terminal intact at Bonny thus controlling access to the sea from Port Harcourt.

The attack on the Midwest Region in September 1967 from Biafra escalated the war. The Navy supported the army from the beginning of the war in the Midwest through the amphibious operation to recapture the river ports of Warri, Koko and Sapele. The Navy landed troops through NNS Lokoja in Koko and Sapele. 38 These two towns were captured with some ease. The support provided by the Navy made the whole of the Midwest riverine areas, including Warri, fall into the hands of federal troops. 32 One important incident that happened during the battle close to Sapele was the rescue of the military governor Timi Ejoor by men of NNS Ogoja. 2 Bonny again was re-attacked. During the war in the Midwest, Bonny was left in the hands of the 7th battalion of the 3rd Marine Commando under the command of Lt. Col. Abubakar. 36 Even though regular supplies of food, ammunition and fuel were made by the Navy to Bonny, thereby boosting the morale of the army, notwithstanding, the island was a very important strategic town in terms of its petroleum resources and geo-strategic value. The timely intervention of naval ships ensured that Bonny, Peterside and the environs remained firmly in the hands of the Nigerian military. 34 The second phase of the Bonny operation thus came to an end on 5 January 1968 in favour of the Nigerian military. The victory at Bonny convinced the British government and Shell-BP of where their true interests’ lay. 43 In one case Shell advanced a royalty of $5.5 million to fund the purchase of more British weapons. Shell controlled 84% of Nigeria’s 580,000 barrels per day. Control over petroleum in the Niger Delta was a paramount military objective for the federal troops during the war.

A plan was put together by the commanders entailing an assault on coastal areas like Calabar and Oron. The long line of naval fleet steamed towards Calabar amidst a riot of engine noise, a blanket of smoke, and radio silence. 44 NNS Penelope led the naval crew from Parrot Island; NNS Nigeria now fell back and gave covering fire to the ships moving in, with NNS Lokoja (landing craft) carrying a battalion of troops for landing. 45 Troops and equipment were landed at Henshaw Town while NNS Ogoja bombarded suspected Biafra locations with her 3-inch anti-shore, anti-aircraft and single barrel gun, of which one of them hit the Anansa naval base. 46

Biafra troops were led by Col. Ogbu Ogi, who was responsible for controlling the area between Calabar and Opobo, and Lynn Garrison was the foreign mercenary attached to this force. Nigerian forces had a fair opposition from the beach but landed successfully. A major disaster was averted from the bombardment (of Calabar) from NNS Nigeria when one shell accidentally landed close to NNS Enugu. 47 The Navy and Army pressed on to take Calabar without any serious incident except the clash of the Nigerian Army with the Biafra forces of Hope Wadell Training Institute, where some Nigerian soldiers led by Major Anthony Ochefu had encamped. 44 Progress made by the Nigerian Army was very slow because they met a serious challenge from the Biafra soldiers. The remaining army troops prepared for the Oron expedition and were discharged to re-enforce the Calabar land battle so that the army could take Calabar. 49 The remaining battalions of the 3rd Division were therefore discharged into NNS Lokoja and landed in Calabar with their arms, ammunition, equipment and stores. 50 That same day Lynn Garrison reached Calabar but came under immediate fire from water and land. For the three days the encirclement lasted, apprehension ran riot within the Nigerian field command. The MV Wirigi completed discharging on the night of the 4th day and returned to Lagos. 51 NNS Lokoja and MV Bode Thomas delivered all the stores to Calabar on 18 October 1967. 2 By the end of the operations, Calabar was securely in the hands of the federal troops. The federal forces started to move north to link up with the First Division at Ikom to seal off the Cameroonian borders close to the East. 53 In late April, 1968, federal forces took over Ikom, Uyo, Eket, Abak, Opobo, and Ikot Ekpeme. 27

Nigeria’s offensive to liberate Port Harcourt did not effectively commence until April 1968, largely on account of Biafra’s blockade of the Port Harcourt channel with a sunken floating woods near the Okrika jetty. The whole terrain was also used as a Biafra mine field. 2 Biafra still controlled Port Harcourt, the centre of Nigeria’s petroleum industry, although the town and the surrounding oil-rich Rivers State were coming under increased pressure from Nigeria’s Third Marine Division. 44 However, on May 19, the Third Marine Commando Division captured Port Harcourt, having already taken the oil refinery at Bomu and Okrika. By this victory, the East was cut off from the sea, thereby denying it the sea lines of communication. 57 Federal forces could now claim de facto control over the country’s major petroleum outlet. Actual production could not be resumed until Biafra forces were evicted from Port Harcourt and the surrounding drilling fields of River State. The Port Harcourt oil facilities had been damaged and needed repair. Production and export continued at a lower level. The Port Harcourt capture by the Nigerian military denied the Biafra administration any claim to economic viability. 58 The Nigerian military regarded the capture of Port Harcourt as a turning point in the war. Gowon claimed that the victory at Port Harcourt gave federal troops the necessary leverage within the international community. He opined that had Biafra held the city of Port Harcourt for another month, no fewer than twelve countries would have supported Biafra. Port Harcourt, no doubt was strategic to the later victories during the civil war and the Nigerian Navy played an important role. Ahoada was the last major town in Rivers State to be taken by the Third Marine Commando Division. 59 Encouraged by the victory, Gowon announced a ‘final offensive’ which was scheduled to begin on August 24, 1968.

After the defeat of Biafra in Bonny, Port Harcourt, Warri, Sapele, Calabar, and Oron, the civil war was reduced to land battles. Except for some occasional smuggling of goods and ammunition and the sea lift of soldiers, the Nigerian Navy was now focused on blockade of the waterways alone. Biafra became landlocked, reducing its chances of tactical victory. Biafra had become overcrowded and impoverished after the riverine territories were occupied by the federal forces. On gaining the upper hand in the civil war on the sea, the Nigerian Navy blockaded the Biafra region leading to the inability of the encircled population to function naturally in the domestic and international realms. 27 The federal blockade denied Biafra any further income from their principal exports of palm oil products and petroleum. 61 It also weakened the Biafra economy.

The problems of Biafra further increased when the Nigerian Navy acquired ships from the Soviet Union during the war. The three fast boats bought from the Russians were loaded in a Russian freighter and discharged on arrival in Lagos. 62 The Russians took their time in bringing the boats up for commissioning. Two patrol boats were commissioned and named NNS Ekun and NNS Elole. 63 On October 16, 1967, the Soviet premier, Alexei Kosygin, had assured the federal government of “Soviet support and cooperation in preserving Nigeria’s unity”. 64 A prolongation of the conflict could bring greater Nigerian dependence on Soviet military ammunitions at the detriment of a good relationship with the British government.

As for the Nigerian territorial waters, until the promulgation by the military of the Territorial Waters Decree of 1967, the limit of Nigeria’s territorial waters was three nautical miles. This limitation was necessary because Britain had always claimed three nautical miles in consonance with customary international law introduced in 1702 according to the utmost range of cannon. 65 The Territorial Waters Decree of 1967 extended Nigeria’s territorial sea from three nautical miles to twelve nautical miles, and in so doing amended section 18(1) of the Interpretation Act of 1964. 2 During the civil war, Nigeria had progressively increased the width of her territorial waters from 4.83 kilometres (3miles) in 1964 to 19.30kms (12miles) in 1967, 67 thereby increasing Nigeria’s waterways, with the Nigerian Navy having a larger sea space to secure. The rationale for the extension was both economic and strategic.

The aim of the federal government was to stop the activities of gun-runners by appropriating as much water area as possible as was compatible with Nigeria’s security. The MV Jozina smuggling incident demonstrated the determination of blockade runners to break the strategic blockade instituted by the federal authorities against Biafra during the war. 68 Even though the MV Jozina master proved stubborn to the Nigerian Navy, his ship was, however, acquired by the Navy and was berthed in the naval base in Lagos. 69 The MV Jozina was repainted in naval colours, and renamed Kwa River. 70 The ship served the Navy as a logistic supply ship, taking supplies, men and equipment to Bonny and Calabar. John Ogun of the Nigerian Ports Authority was appointed as the First Master/Captain. 49

In February 1969, the Nigerian Navy re-organised its administrative structure. The main objective was to introduce an area command in view of the civil war and to give the organisation an administrative authority. The new area command was therefore to be the Lagos area, and the administrative authority was the Naval Officer in Charge (NOIC), Lagos. 63 The introduction of this change brought the two establishments, Naval Dockyard, Victoria Island and the Armament Depot in Kirikiri, under the control of NOIC, Lagos. At the initial stage of the re-organisation, the NOIC, Lagos was also the Commanding Officer, NNS Beecroft, the naval base. It was at this stage that the naval headquarters was relocated to the Ministry of Defence, Lagos, from NNS Beecroft. 2

In 1969, the Nigerian Navy was already thinking of what type of future it wanted for itself with the cessation of the sea battles. The Nigerian Navy acquired three important establishments: Apapa Elemu, Omo Sawmill Village, and the Armament Depot Kirikiri. For the development of these places, the Navy created a Naval Projects Development Committee which had Captain Soroh as its chairman. 74 The planning of the Nigerian Navy Dockyard at Wilmot Point, Victoria Island, was further examined by a sub-committee of the projects committee which developed the final details. The committees took into consideration the size of ships to be bought for the rest of the 20th century. A new dockyard was commissioned on 27 September. The Omo Sawmill Project became the Naval Stores and Motor Transport Yard Project, 2 and Apapa Elemu was renamed the Command and Training Centre Project. 76 Jetties in various locations around Nigeria, including Calabar, Port Harcourt, and Lagos, were to be developed, bearing in mind the proposed expansion of the Navy after the Nigerian civil war.

The Nigerian Navy lost one of its capital ships, NNS Ogoja, during the war. Under the command of Lt. Commander Ajanaku, NNS Ogoja went aground at a point two miles off Akassa lighthouse. 2 On 25 October 1969, NNS Ogoja was abandoned as a wreck and became the first ship to be lost by the Navy due to grounding. With the loss of NNS Ogoja the Navy was now short of important fighting ships. A decision was, however, made to buy ship for the Navy. 78 The Navy had placed orders for two Corvettes just before the civil war ended and by September 1970, the Navy launched a new ship NNS Dorina. 79 The establishments in Calabar and Port Harcourt were also being considered for improvement. However, during the war, the Nigerian Navy’s main priority was on the command and training centre and the naval dockyard, both of which were in Lagos. 80

The Nigerian Navy successfully supported the Nigerian Army to take over the Bight of Bonny from Biafra forces and mounted an effective blockade which forced the tide of the war positively on the side of the federal government. 49 The effectiveness of the naval blockade was instrumental to the eventual outcome of the civil war. The fate that befell the Biafra military was inevitable because of its vast strategic limitations. In the first place, it relied (except for a few boats, aircraft and the seized ship it took away from Nigeria) almost exclusively on its ground forces. Even though the Nigerian Air force was at its infancy, it had almost no contest in the Nigerian airspace. The Biafra army was also ill-equipped and ill-trained. 82 According to Chuma Ifedi, “troops welfare was next to Zero …. The boys in the trenches lived like animals with little or no clothing. Only lucky units ate once a day.” 83 Most troops often went a whole day without a meal.

John de St. Jorre’s account of the end of the war in the East Central State of Nigeria appears to be pro-federal:

There was no ‘genocide’, massacres or gratuitous killings; in the history of warfare there can rarely have been such a bloodless end and such a merciful aftermath in the Nigerian war. 84

Pope Paul’s assessment during the benediction of January 11, 1970, with its reference to a kind of genocide and possible reprisal against defenceless people in Biafra, was typical of the position of the Catholic Church. 85 Nigeria’s victory was largely because of its access to superior armaments, the bombardment of Biafra land by sea and air, logistic advantage over the Biafra military and overwhelming international support.

Contribution of the Navy to the Defeat of Biafra

‘Communications’ is a general term designating the lines of movement by which a military body, army, airmen or fleet, is kept in living connections with the national power of a state. Sea lines of communication can be seen also in military terms as lines for defensive and offensive use. It can be a source of victory to those who have control of the sea environment and defeat for those who were denied its use. This also is peculiar to those land battles that have correlation with sea battles because an army is immediately dependent upon supplies frequently renewed by the support of a maritime power. Sea lift has been officially defined as a naval role. The strategic value of the Nigerian Navy during the civil war lies in its unrivalled capacity to operate in the three dimensions of war, and to communicate with the campaign on land. From this perspective, the Nigerian Navy was thus able to sustain the resources used on the battle front by the Nigerian Army, making the Nigerian land force have a momentum against the enemy otherwise victory may not have come or could have been delayed.

The amphibious operation led by the Navy in Bonny became the first important signpost for the Nigerian maritime force. Amphibious operations involving the navy can come in different shapes and forms. The ability of the Nigerian military to strike at Bonny from an advantageous direction provided a flexibility which is one of the greatest strategic assets that a maritime power can have. The capacity to use the sea as a medium of surprise from which to project power ashore is an important benefit for any military in the world. The Navy, during the civil war, was dependent only on surface ships. The surface ship acted as a mobile platform for the bombardment of the hinterland and the shores. Combatant ships like the frigate NNS Nigeria used by the Navy during the war have a general purpose capability. Essentially intended for the escort of non-combatant ships, it could also be useful for patrol and support aerial strikes. 86 For amphibious operations, a landing craft such as NNS Lokoja and the Nigerian Ports Authority ships were significant for the operational role of transportation of food, ammunition, and troops. The landing of troops in Bonny had economic and strategic consequences. It culminated in the encirclement of Biafra, shifting the war fronts around the Biafra hinterland and thereby spreading the Biafra military and weakening it in all fronts. Operations like that of Bonny, and later Calabar and Port Harcourt, are of considerable importance to the outcome of the hinterland wars fought by the army during the civil war. Navies conducting large scale amphibious operations have generally tried to win high levels of sea-control first, even though it may be hazardous and difficult to achieve. According to Corbett, “the object of naval warfare must always be directly or indirectly either to secure the control of the sea or to prevent the enemy from securing it.” 87

In conclusion, it was the blockade role of the Nigerian Navy that facilitated the victory over Biafra forces. The navy deprived Biafra of the opportunity to hold on to the Bonny terminal, export oil and deploy the foreign currency earned to purchase arms from the black market. It also denied Biafra access to an otherwise open route to convey purchased weapons into Biafra (Cameroon having become uncooperative). Above all, the Navy’s blockade created a siege mentality, a psychological feeling of being encircled with nowhere to go. Finally, the Nigerian Navy’s tactical support to the Nigerian Army in the first year of the war gave the federal troops quick successes. However, in the last two years of the war, Biafra had become landlocked and as such the Navy had very little tactical influence, which slowed down the Army’s successes in the final nineteen months of that war, notwithstanding the other factors that slowed down the federal troops. Clearly the Nigerian Navy was a key factor in determining the ultimate outcome of the conflict.

(Return to August 2016 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

- John Jonah, “Naval Engineering and Fleet Readiness: Challenges and Transformation Strategies for the Nigerian Navy” (Paper presented at the Engineering Conference meeting for the Nigerian Navy, Sapele, Delta State, Nigeria, September 25-30, 2011), p.7. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Nelson B.Soroh, A Sailors Dream, Autobiography of Rear Admiral Nelson Bossman Soroh (Lagos: Crucible Publishers, 2001), p.226. ↩

- John Stremlau, The International Politics of the Nigerian Civil War, 1967- 1970 (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1977), p. xvii. ↩

- Ibid., p.36. ↩

- Soroh, A Sailors Dream, p.227. ↩

- Interview with Rear Admiral Ola Adedeji (former Commandant, Nigerian Defence College) at Wuse in Abuja on 10 May, 2012. ↩

- Soroh, A Sailors Dream, p.227. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Jonah, “Naval Engineering and Fleet Readiness: Challenges and Transformation Strategies for the Nigerian Navy”, p.7. ↩

- Soroh, A Sailors Dream, p.224. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Interview with Commodore A. Momodu at Sapele on the 10 March 2007. ↩

- Soroh, A Sailors Dream, p.224. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Obinalli Kelechi, United States Foreign Politics and the Internationalization of the Biafran War, 1967- 1970 (Mississippi: University of Southern Mississippi Press, 2008), p.11. ↩

- West Africa, No. 2770, August 25, 1968, p.600. ↩

- Kelechi, United States Foreign Politics and the Internationalization of the Biafran War, p.50. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., p.51. ↩

- Ibid., p.50. ↩

- Akin Omosefunmi and F. Akinlonu, 30 Days in Power, 4 years in Command: The Story of Vice Admiral Akin Aduwo (Rtd) (Lagos: Advent Communications, 1997), p.40. ↩

- Interview with Vice Admiral AkinAduwo at Lagos on the 13 October 2011. ↩

- Omosefunmi and Akinlonu, 30 Days in Power, 4 years in Command, p.48. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Stremlau, The International Politics of the Nigerian Civil War, p. xvii. ↩

- Nigerian Navy, The Making of Nigeria Navy: A Chronicle of Events, p.95. ↩

- Soroh, A Sailors Dream, p.229. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Stremlau, The International Politics of the Nigerian Civil War, p. xvii. ↩

- Interview with Vice Admiral Akin Aduwo. ↩

- Omosefunmi and Akinlonu, 30 Days in Power, 4 years in Command, p.48. ↩

- Interview with Vice Admiral AkinAduwo. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Soroh, A Sailors Dream, p.239. ↩

- Ibid., p.237. ↩

- Ibid., p.239. ↩

- Interview with Vice Admiral Akin Aduwo. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Soroh, A Sailors Dream, p.239. ↩

- Interview with Vice Admiral AkinAduwo. ↩

- John de St Jorre, The Nigerian Civil War (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1972), p.141. ↩

- Omosefunmi and Akinlonu, 30 Days in Power, 4 years in Command, p.57. ↩

- Interview with AkinAduwo. ↩

- Omosefunmi and Akinlonu, 30 Days in Power, 4 years in Command, p.58. ↩

- Ibid. However, the account presented by Alabi Isama appears to be slightly different. According to him, “the Navy, with two ships, started shelling from April 14th until the landing of troops on April 18th 1968. This was to trick the Biafrans to divert their attention to Oron, while Isaac Boro moved into Jamestown. The three days of naval shelling and bombardment were very successful, but during the landing at Oron, our troops missed the landing sight and landed at Parrot Island, near Oron, at night. The firing and bombing from the naval guns provided the lights, including lightning from the rain” Alabi Isama, The Tragedy of Victory(Ibadan: Spectrum Books, 2013), p.209 ↩

- Omosefunmi and Akinlonu, 30 Days in Power, 4 years in Command, p.57. ↩

- Interview with Akin Aduwo. ↩

- Soroh, A Sailors Dream, p.247. ↩

- Ibid., p.248. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Isama, The Tragedy of Victory, p.213 ↩

- Stremlau, The International Politics of the Nigerian Civil War, p. xvii. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Omosefunmi and Akinlonu, 30 Days in Power, 4 years in Command, p.57. ↩

- Stremlau, The International Politics of the Nigerian Civil War, p.75. ↩

- Ibid., p. xvii. ↩

- West Africa, No. 2660, May 25, 1968, p.621. ↩

- Stremlau, The International Politics of the Nigerian Civil War, p. xvii. ↩

- Ibid.,p.220 ↩

- Kelechi, United States Foreign Politics and the Internationalization of the Biafran War, p.250. ↩

- Soroh, A Sailors Dream, p.250. ↩

- Stremlau, The International Politics of the Nigerian Civil War, p.220. ↩

- M.A. Ajomo, “Protecting Nigeria’s Four Sea Zones” (Paper presented at a workshop on smuggling and coastal piracy in Nigeria Institute of International Affairs (NIIA), Lagos, Nigeria, February 22-23, 1983), p.17. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Okon Ekpeyoung, “Geographical Perspectives on the Security of Nigeria Waters”, (Paper presented at a workshop in the NIIA, Lagos, Nigeria, February 22-23rd, 1983), p.27. ↩

- Ajomo, “Protecting Nigeria’s Four Sea Zones” p.18. ↩

- Olutunde Oladimeji, “Integrated Maritime Guard System: Security Arrangement for Policing Inland Waters, Harbour, and Coastal Approaches against Smuggling and Coastal Piracy in Nigeria”, (Paper presented at a workshop in the NIIA, Lagos, Nigeria, February 22-23, 1983), p.27. ↩

- Soroh, A Sailors Dream, p.249. ↩

- Interview with Akin Aduwo. ↩

- Soroh, A Sailors Dream, p.250. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., p.274. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Rear Admiral Soroh writing on the acquiring of these three important establishments said, “I had uppermost in my mind the ultimate growth of the Nigerian Navy”. Soroh, A Sailors Dream, p.280. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Interview with Commodore A. O. Oladimeji at Agbara in Ogun State on the 9th of October, 2011. ↩

- Omosefunmi and Akinlonu, 30 Days in Power, 4 years in Command, p.57. ↩

- Soroh, A Sailors Dream, p.280. ↩

- Interview with Akin Aduwo. ↩

- Soroh, A Sailors Dream, p.281. ↩

- Omosefunmi and Akinlonu ,30 Days in Power, 4 years in Command, p.62. ↩

- de St Jorre, The Nigerian Civil War, p.404. ↩

- Stremlau, The International Politics of the Nigerian Civil War, p.367. ↩

- Eric Grove, The Future of Sea Power (London: Rout ledge, 1990), p.3 ↩

- Westcott, Mahan on Naval Warfare, p.83. ↩

One Response to Nature and Impact of Involvement of the Navy in the Nigerian Civil War, 1967-1970