Contents:

The Setting

The Domestic Context

Presidential Crisis Decision Making

Douglas Peifer

US Air War College

Setting

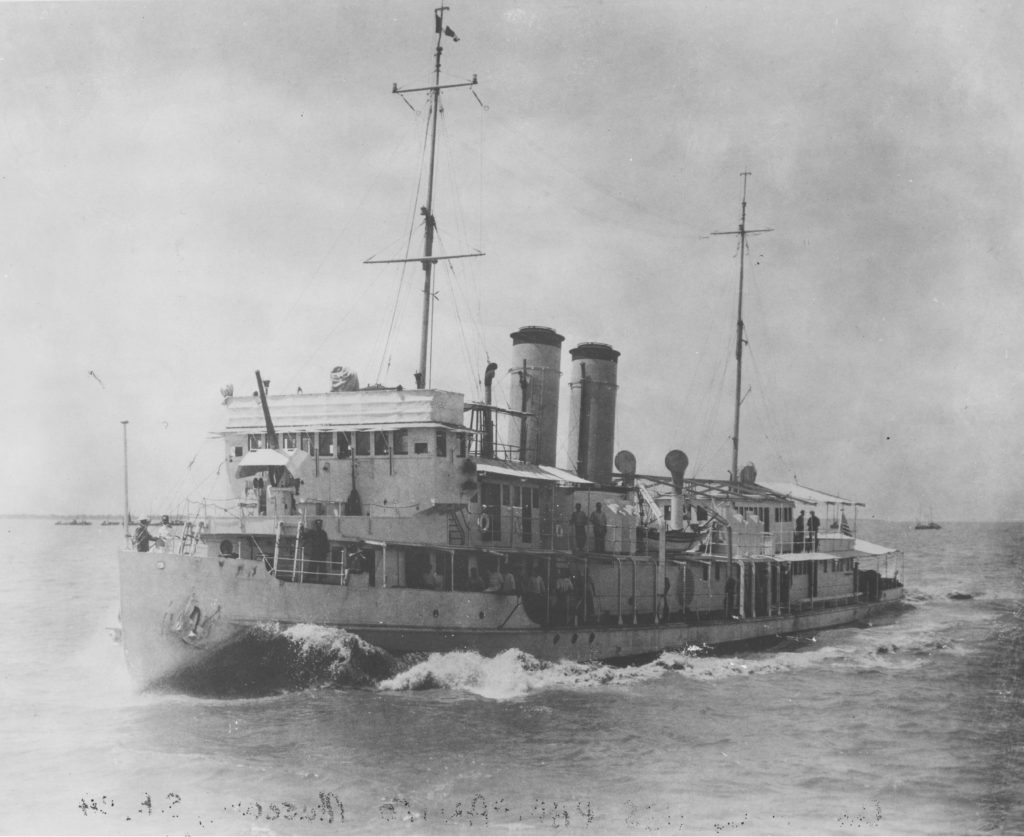

Last December marked the 80th anniversary of the sinking of the US gunboat Panay by Japanese aircraft, an incident that predated the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor by four years. The sinking of the Panay was frontline news, but unlike the reaction to the sinking of the Maine in 1898, the crisis elicited more apprehension than outrage. Public opinion and Congress feared an overreaction on the part of the executive branch, with isolationist papers and politicians asking why US naval vessels had been stationed in China in the first place. A broad spectrum of the public feared that FDR’s response would somehow entangle the United States in the ongoing Sino-Japanese war, and Congress sent a clear signal that it had no intentions of authorizing any sort of military response.

The USS Panay underway on Yangtze, date unknown (Naval History and Heritage Command, Photo Archives, Photograph # NH 11353)

The Setting

On August the 22nd, 1937, Admiral Harry Yarnell, Commander in Chief of the US Asiatic Fleet, dispatched a stern protest to the Commander of the Japanese Third Battle Fleet whose ships were firing on Chinese positions near Shanghai’s International Settlement. Yarnell, joined by his British and French counterparts, complained that Japanese destroyers were shooting directly over his flagship and other non-belligerent naval ships. He objected that the Japanese were endangering neutral shipping caught in the crossfire between Chinese and Japanese forces, noting that two days earlier a shell had landed directly on the deck of his flagship, killing one American sailor and wounding eighteen. Admiral Yarnell urged the Japanese admiral to shift his warships to a different anchorage so that the USS Augusta and other neutral vessels moored off Shanghai’s bustling waterfront, the Bund, would not be further endangered. 3 Yarnell’s request was duly conveyed to Tokyo, and while the Japanese government responded reassuringly that it had directed its forces to exercise utmost caution so as to avoid incidentally damaging Western embassies or ships, the reality was that the escalating conflict between Imperial Japan and Nationalist China threatened long-established Western interests.

These interests took many forms, from large international settlements with extraterritorial jurisdiction at dozens of treaty ports along China’s coast to factories, railroads, and warehouses throughout the country to missionary schools and churches tucked deep in the country’s hinterland. By the mid-1930s, the US had around 2,400 ground troops in China, with 528 Marines on station in Beijing, 785 Army troopers posted to Tientsin, and 1,100 Marines stationed at Shanghai. 4 In addition, units of the US Asiatic Fleet regularly visited Chinese ports, with Admiral Yarnell’s flagship the Augusta (a heavy cruiser) anchored conspicuously at Shanghai’s Battleship Row throughout the summer and fall of 1937. Lastly, the riverine gunboats of the US Yangtze Patrol provided a reassuring presence deep into the interior of China for the scattered American missionary outposts, schools, trading enclaves and businesses strung out along South China’s major trade corridor, the Yangtze River.

As clashes between Kuomintang and Japanese soldiers escalated into full-fledged (though undeclared) war in July 1937, the environment in which US troop detachments and gunboats operated became increasingly dangerous. The isolated gunboats of the Yangtze Patrol were particularly vulnerable, usually operating as detached units and lacking the firepower to defend themselves from anything more serious than light arms fire. On August 10, Secretary of State Cordell Hull clarified the mission of the Yangtze Patrol, specifying that both offensive and coercive operations against foreign governments fell outside its mission set. He emphasized that the Yangtze Patrol’s primary function was to protect American nationals, with a secondary function to protect American property. American forces in China were “in no sense expeditionary forces. They are not in occupation of an enemy territory nor are they defending territory of the United States. They are expected to protect lives but they are not expected to hold positions regardless of hazards. They would be expected to repel threatened incursions of mobs or of disorganized or unauthorized soldiery, but they would not be expected to hold a position against … armed forces of another country acting on express high authority.” 5

By this time, Sino-Japanese fighting had spread from Northern China and the Beijing area to Shanghai and the Yangtze River valley. Americans, other Westerners, and Chinese civilians became caught in the crossfire, with both sides showing a general disregard for non-combatant lives and neutral property.

It soon became apparent that Japanese aircraft and artillery were becoming the main threat to American lives and property in China. Relaying a report from the US embassy in Nanking (Nanjing) to the American ambassador in Japan, Secretary of State Hull remarked that “Sooner or later some incident is going to happen resulting in the death or injury of American citizens going about their legitimate occupations within the interior of China where such dangers should not exist.” Hull directed Ambassador Grew to deliver an aide-mémoire to the Japanese Ministry for Foreign Affairs urging Japan to “refrain from attacks upon defenseless cities, hospitals, trains, and motor cars etc.” The American aide-mémoire noted that while Japan claimed it was not at war with China, Japanese aircraft were conducting raids deep into the interior of China with “consequent serious damage to the rights of other nations.” 6

Hull’s misgivings were justified. As Japan proceeded with military operations around Shanghai and then pushed up the Yangtze River toward the Republic of China’s capital at Nanking, a growing number of complaints reached the US Embassy about incidents in which Americans had been hurt, attacked, or witnessed brutal attacks on Chinese employees and civilian facilities. On the 17th of September, Ambassador Joseph Grew lodged an official complaint with the Japanese government, noting that Japanese military forces were showing a reckless disregard for US lives and property. Japanese aircraft, Grew admonished, had even subjected American humanitarian and philanthropic establishments in China to savage attacks. Three days later, Ambassador Grew again called upon the Japanese Foreign Minister Kōki Hirota, warning him of “the very serious effect which would be produced in the United States … if some accident should occur in connection” with the Japanese navy’s announced intention to bomb Nanking. Grew recalled that he employed the most emphatic language, reminding Hirota that “we must not forget history…neither the American Government nor the American people had wanted war with Spain in 1898, but when the Maine was blown up nothing could prevent war.” 7 Ambassador Grew feared that overeager Japanese aviators might attack a US ship or contingent of marines irrespective of restraining directives to exercise utmost caution. He blamed young, hotheaded Japanese aviators for causing trouble, commenting in his diary that “having once smelled blood they simply fly amok and ‘don’t give a damn whom or what they hit.’” 8

Less than three months after warning Hirota that overeager Japanese aviators might plunge relations between the US and Japan into a crisis, Grew found himself issuing orders to the American embassy staff in Tokyo to begin planning for a hurried departure. The ambassador had received word that Japanese aircraft had sunk the USS Panay on 12 December as it lay at anchor upstream of Nanking.

The Domestic Context

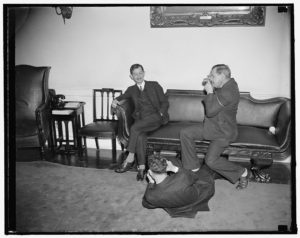

Secretary of State Cordell Hull arriving at White House to discuss Far East situation, Aug 1937 (LOC Image #LC-DIG-hec-23201)

Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his advisors were keenly aware of the strengths of isolationism as they attempted to forge a coherent strategy for dealing with Japanese aggression in East Asia during the 1930s. Cordell Hull, FDR’s Secretary of State, claimed that in the spring and early summer of 1937, the United States had contemplated relinquishing its extraterritorial rights in China and had contacted the British to begin exchanging views on the topic of restoring full sovereignty to China. 9 The outbreak of fighting put the matter of the American military presence in China on the front burner, where it would remain until the Panay was sunk in December. Harold Ickes, FDR’s Secretary of the Interior, recorded cabinet deliberations that reveal that both the President and Vice President were deeply ambivalent about the presence of American troops in China. 10 Vice President John Nance Garner, when told that one couldn’t remove American troops without inadvertently encouraging further Japanese aggression, exploded, angrily asking “Are we going to keep our troops in China for twenty or fifty or a hundred years?” For Garner, the issue was clear. The United States “oughtn’t to have soldiers and Marines in foreign countries,” with the Texan elaborating that “we wouldn’t take it in good part if Japan insisted on having marines in San Francisco.” FDR was more circumspect, asking Admiral Leahy how many Marines were in Shanghai, and then sighing that “he wished they were not there.” When Leahy pointed out that the Marines were protecting four thousand Americans in the city, the President countered that “there were about twenty-five thousand Americans in Paris and not a single Marine.” Ickes recorded that the President reluctantly agreed with Hull and Leahy that the marine contingent could not be removed given the present situation. Ickes concluded that “It is the old case of not doing something when it can be done and then when a crisis arises, deciding that it can’t be done then.” 11

Roosevelt predicted that some Americans were going to get hurt, and instructed Leahy to work out plans to evacuate those American who wished to leave. The president, according to Secretary of the Treasury Morgenthau, told Garner that the administration would base its policies in the Far East “on the hope of Japanese disaster, which could be produced by a rise in the strength of Russia and China and a revolt on the part of the Japanese population against militarism.” 12 Yet hope is not a strategy, and FDR would find that creating policies that supported his aspirations was difficult given the domestic political climate which prevailed within the United States.

If the president, vice-president, and Secretary of the Interior were frustrated that outdated treaty rights dating back to the Boxer Rebellion had put American forces in a vulnerable position from which it was difficult to withdraw without appearing weak, isolationist Congressmen and Senators were appalled. Immediately after the outbreak of fighting in China in July, Representative Hamilton Fish of New York announced to the press that he would introduce legislation forcing the administration to relinquish extraterritorial rights in China. Fish challenged his fellow House members to come up with a single good reason for maintaining American troops and gunboats in China. 13 Senator Lewis of Illinois raised the same point in the Senate the next day, with Representative George Holden Tinkham of Massachusetts submitting a resolution for the withdrawal of all American forces from Northern China on 9 August. As the situation in China deteriorated, more isolationist Congressmen and Senators took to the floor, with Representative Voorhis of California exclaiming on the 17th of August that America had everything to lose and nothing to gain by keeping marines and gunboats in China. 14

Public opinion was divided on the matter. On August 5th, Gallup conducted a poll asking whether the United States should withdraw all troops in China in order to keep from getting involved in the fighting, or keep them there to protect American rights. Fifty-four percent of those polled answered “withdraw,” forty-six responded “Remain.” Yet when the president remarked to some journalists that same day that Americans in China had been urged to leave and those who decided to remain did so “at their own risk,” hundreds of messages poured into the White House from missionary leaders and businessmen stunned at the statement. 15 English language newspapers in China, such as the Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury, the China Weekly Review, and the North China Daily News, reflecting the sensibilities of the American expatriate community in China, ascribed the president’s remark to an oversensitivity to Congressional isolationists and peace activists.

The president had to reconcile the wishes and recommendations of his foreign and security policy advisers with the realities of the political situation at home. When Admiral Yarnell requested additional marines to reinforce the marine detachment in Shanghai in mid-August, the president had endorsed the request in the face of considerable pressure. But when Yarnell and Hornbeck, the former the on-scene military commander in Shanghai and the latter the State Department’s East Asia expert, asked for an additional two cruisers (watered down from an initial request of four cruisers) at the end of the month, FDR turned down the request emphatically. 16 And when Yarnell issued a statement to the press explaining that American forces had the duty and obligation to protect American citizens in China even at the risk of being exposed to danger, the president curtly instructed Leahy that “hereafter any statement regarding ‘policy’ contemplated by the Commander –in-Chief Asiatic Fleet must be referred to the Secretary of the Navy for approval.” 17 Harold Ickes, more attuned to domestic considerations than his State Department and Navy colleagues, recorded his assessment candidly in mid-September. A political animal and one of the key implementers of the New Deal, Ickes confided to his private diary that

There isn’t any doubt that we are in a bad spot so far as the Sino-Japanese situation is concerned. When the President some time ago warned all Americans to leave China or to stay there at their own risk, a great protest went up, especially from the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai. As usual, Americans who went abroad to engage in business because of the big profit that they thought they might make expect us to sacrifice thousands of lives if necessary and millions of treasure in an attempt to protect their investments when we can’t do it anyhow. It all seems so stupid to me…. After all, there is no compulsion to invest money in foreign enterprises and it ought to be at the risk of the investor. Certainly we oughtn’t to be expected to go to war, with all the dreadful consequences involved, to protect people who are doing something they want to do and are doing [so] voluntarily. 18

Roosevelt presided over a back and forth struggle between isolationists in Congress and internationalists in the State and Navy, calling upon administration allies in Congress to provide him with room for maneuver. He attempted to steer a course that would enjoy public support, opposing recommendations he feared would result in a backlash but resisting calls to invoke the full panoply of restrictions embedded in the Neutrality Act. The advice and counsel he received from members of the cabinet was divided, as were the inputs they received from their subordinates. 19

The administration had to tread very carefully when dealing with the Sino-Japanese conflict in the summer and fall of 1937. Isolationist sentiment expressed itself not only in calls for the rapid withdrawal of US military units in China and in demands that FDR implement the Neutrality Act, but in a deep-seated skepticism toward any joint, multinational, or international response to the crisis.

With the passage of time, it has becoming tempting to characterize the isolationists as know-nothing provincials, Republican holdouts embittered by the New Deal, or the offspring of the mid-western “hyphenated Americans” who had opposed Wilson’s tilt to the Entente in World War I. Yet isolationist sentiment was wide-spread even in the circles most enthused about the New Deal, with college professors, ministers, and many intellectuals warning against any administration schemes that envisioned the United States organizing collective responses to overseas aggression. Charles Beard serves as an example of a progressive, highly educated isolationist. Writing in the Political Quarterly that fall, Beard commented that “With much twisting and turning, the American people are renewing the Washington tradition and repudiating both the Kiplingesque imperialism of Theodore Roosevelt and the universal philanthropy of Woodrow Wilson.” They are showing a “firm resolve not to be duped by another deluge of propaganda – right, left, or centre.” 20 While Beard supported the administration’s New Deal and was sympathetic to its domestic activism, he opposed FDR’s internationalist tendencies. Responding to the internationalist argument, Beard wrote in the New Republic that

It is easy to get into a great moral passion over the distant Chinese. It costs nothing now, though it may cost the blood of countless American boys. It involves no conflict with greedy interests in our own midst. It sounds well on Sunday… [But] Anybody who feels hot with morals and is affected with delicate sensibilities can find enough to do at home, considering the misery of the 10,000,000 unemployed, the tramps, the beggars, the sharecroppers, tenants and field hands right here at our door. 21

A few voices pushed back against the strong current of isolationism in the fall of 1937. Senator M.M. Logan of Kentucky advised the administration to act more forcefully, elaborating to journalists that “I am opposed to war, but I am also opposed to running for a hole every time anyone says ‘boo.’ I think the fleets of a group of nations blockading Japan would stop the present hostilities. But it would have to be collective action by several nations.” 22 FDR’s Secretary of the Navy, Claude Swanson, made in similar point in Cabinet discussions, telling the president that the Navy staff was of the opinion that “if it was considered necessary to put Japan in its place, this was the right time to do it, with Japan so fully occupied in China.” The president ignored Logan’s public call, and smilingly chided Swanson that he [FDR] was a pacifist and had no intention of making any warlike moves. 23

Presidential Crisis Decision Making

Japanese naval aircraft attacked the USS Panay in the early afternoon of Sunday, 12 December 1937. The ship sank beneath the muddy surface of the Yangtze shortly before four in the afternoon. The initial attack destroyed the ship’s transmitter, with the Panay’s survivors hiding in the riverbank reeds until nightfall as they feared that the Japanese intended to kill them. As word reached the Commander of the United States Yangtze Patrol and the American ambassador to China that British gunboats had been subjected to Japanese artillery and air attacks that Sunday afternoon, a sense of alarm began to grip State and Navy Department personnel in Hankow. Ambassador Johnson sent an urgent telegram to Washington shortly before midnight China time letting the Secretary of State know that nothing had been heard from the Panay since 1335. At 930 on Monday morning (Sunday evening in Washington), the American ambassador received a telephone call from an American missionary doctor in Anking relaying the information that the Panay had been sunk, with fifty-four survivors gathered in the town of Hohsien. The Ambassador and the Commander of the United States Yangtze Patrol rushed to inform their respective superiors of the news. By late Sunday evening Eastern Standard Time, State and Navy leadership in Washington had been informed that the Panay was destroyed.

As Washington began to grapple with the news, the Japanese government sought to defuse the situation by immediately apologizing for the incident at multiple levels and across time zones. 24 1937, vol.4, 497-98.] In Tokyo, Foreign Minister Hirota broke with diplomatic protocol by personally visiting the American embassy to express his regret for the incident. 25 The Japanese Navy Minister meanwhile sent his senior aide to the US naval attaché in Tokyo to convey the Navy Minister’s “sincerest regret to this unhappy accident,” with the Chief of Staff of the Japanese China Sea Fleet paying a formal call to Admiral Yarnell on the flagship Augusta in Shanghai to apologize and offer medical assistance. 26 In Washington, the Japanese ambassador requested an urgent meeting with the US Secretary of State, intent on conveying his government’s full and sincere apologies for the “very grave blunder” which had occurred.

The barrage of apologies from Japanese officials gave the administration little time to digest what had happened to the Panay, let alone conduct protracted internal debates before responding. Secretary of State Hull put off meeting the Japanese ambassador until 1 pm on Monday so that he could first consult with the White House. Hull had conferred with the officers of the Far Eastern Division the previous evening, and met with them again early Monday morning to deliberate what sort of recommendations the State Department should make. The initial consensus of opinion was that Japan’s behavior had been outrageous, but given isolationist sentiment, the United States was in “no position to send sufficient naval forces… to require the Japanese to make the fullest amends and resume something of a law-abiding course.” 27 Admiral Leahy, the Chief of Naval Operations, participated in the discussion Sunday evening, and had been dismayed by the weak response contemplated. He advised the president that it was “time to get the fleet ready for sea, to make an arrangement with the British Navy for joint action, and to inform the Japanese that we expect to protect our nationals.” 28

The president received conflicting counsel from his inner circle as the crisis broke. The president’s instinct was to express shock, demand an apology, but wait until all facts were assembled before offering more precise terms of settlement. The Naval Court of Inquiry convened to investigate what had happened took a week to file its official account; the journalists who had been onboard the Panay, in particular Colin MacDonald for The Times of London and Norman Soong for the New York Times, worked on faster deadlines. Before even arriving in Shanghai with the other dazed and wounded Panay survivors, MacDonald and Soong somehow managed to send the first eyewitness accounts of the bombing. Over the coming days, more eyewitness accounts would make their way into the papers, with the incident dominating the news cycle.

While the president and his advisers waited for the findings of the Naval Court of Inquiry, they discussed several different options that might underline the gravity and urgency of the situation. These ranged from imposing a naval blockade on Japan to organizing a joint demonstration of force with the British to using economic tools to punish the Japanese. Each option, after careful consideration, was shelved or watered down.

Secretary of the Navy Claude Swanson, though old and in poor health, was enraged by the attack and “shouted for war in his feeble voice” during the cabinet meeting held on 17 December 1937. 29 Swanson made his case forcefully despite difficulty speaking, arguing that war with Japan was inevitable. Given this unfortunate reality, it was better to fight Japan now while its military was bogged down in China rather than wait until Japan had consolidated its hold over the mainland. Returning to a point he had made months earlier, Swanson pointed out that Japan was highly dependent on imports and therefore vulnerable to naval pressure. Admiral Leahy, the Chief of Naval Operations, advised the president to send the ships of the fleet to navy yards “without delay to obtain fuel, clean bottoms, and take on sea stores preparatory for a cruise at sea.” 30 He outlined the idea of imposing distant blockade on Japan in cooperation with the British, a concept that caught FDR’s fancy. After listening to Swanson vent his anger and call for war, FDR painted the broad contours of the concept to his cabinet. The president viewed a distant blockade as less drastic than fleet action, and remarked that the US Navy could blockade Japan from the Aleutian Islands to Hawaii to Guam, with the British taking over the blockade from there to Singapore. FDR asserted that a blockade was “comparatively simple task which the Navy could take care of without having to send a great fleet.” He believed that a joint Anglo-American blockade would bring Japan to its knees within a year. 31 The concept, however, required collaboration with the British Navy, and would put thousands of American civilians still in China – as well as the US troop detachments at Beijing, Shanghai, and Tientsin – at risk. FDR realized that while many Americans were appalled by Japanese behavior in the Far East, few wanted to go to war with Japan over American gunboats on the Yangtze or Japanese atrocities in Shanghai, Nanking, or elsewhere.

If imposing a naval blockade went too far and constituted an act of war, sending a powerful naval force to the area to show the flag offered an alternative that would send a strong signal. The British had suggested a joint display of force back in November, only to be rebuffed by the Americans. As news of the Japanese attacks on the HMS Ladybird, HMS Bee, and the USS Panay reached London, the British government reached out to Washington once again. Noting that they were “fully aware” that the American government was unable to participate in “joint actions,” the British suggested that their two governments might synchronize their responses since the Japanese attacks on vessels of both nations “could not possibly have been the result of accident” according to their sources. 32 The British government attached great importance to creating a united Anglo-American front, urging the Americans to move their fleet and assuring them that “in such circumstances Great Britain would undoubtedly increase her own Far Eastern naval contingent.” 33 The message delivered by the British Ambassador to Cordell Hull the next day was somewhat more circumspect; while reiterating that the British believed the Japanese were following a policy of firing upon the nationals and warships of other nations in a most “reckless, criminal, and deliberate manner,” the British government conceded that it was doubtful whether either Britain or the United States could assemble a naval force sufficiently impressive to deter the Japanese from further outrageous behavior. 34

The British government, when push came to shove, encouraged the United States to take a strong stance toward Japan, desired joint action, but was unable to contribute to the strong display of force it advocated. On the evening of the 16th December, Roosevelt met with British ambassador Lindsay and Secretary of State Hull to explore the matter of naval cooperation more fully off the record. Returning to the concept of a naval blockade or “quarantine” of Japan, FDR grew increasingly enthusiastic as he outlined the concept to the British ambassador. If Japan committed another outrage, the British and American navies should implement a cruiser blockade of Japan, keeping their battleships to the rear. The French and Dutch would have to be brought onboard, with the blockade supplemented by a general embargo of Japanese goods. Roosevelt elaborated that there was no need for the British to send a fleet, and that the dispatch of cruisers, destroyers, and submarines would suffice, perhaps backed by one or two battleships. Reporting on the conversation to Foreign Minister Eden, Lindsay concluded

From the foregoing you may think that these are the utterances of a hair-brained statesman or of an amateur strategist, but I assure you that the chief impression left on my own mind was that I had been talking to a man who had done his best in the Great War to bring America speedily on the side of the Allies and who now was equally anxious to bring America in on the same side before it might be too late… 35

Roosevelt became intrigued with the concept of blockading Japan after the Panay’s sinking. In his mind, a blockade did not equate to a declaration of war, hence his use of the more innocuous term he had tested the previous October, that of a “quarantine.” British officials from the Prime Minister down, no doubt drawing upon their experience in the First World War, were skeptical of this distinction. The Foreign Office favored a joint demonstration of force, a concept it had advocated months before. Both options required a modicum of staff discussions between the US Navy and the Royal Navy, though the administration knew that even a whiff of such discussions would cause an uproar in Congress and the public. On December 23rd, FRD asked Admiral Leahy and Captain Royal E. Ingersoll, director of the US Navy’s War Plans Division, to attend a secret meeting at the White House along with the Secretaries of State and Treasury. Ignoring Hull’s misgivings, FDR instructed Ingersoll to go to London for the purpose of making “preliminary arrangements, if we could, with the British for joint action in case of war with Japan.” 36

Domestic realities made it difficult for the president to openly engage in coercive diplomacy. In groping for a way to respond to aggression without resorting to war, FDR toyed with the idea of using the United States’ economic power to exert pressure without force. This would be particularly useful if the Japanese either refused to pay indemnities for their attack on the Panay, or if they dragged their feet and quibbled about the damages demanded. During the first cabinet session after the Panay’s destruction, FDR declared that there were lots of ways of fighting without declaring war, indicating that economic sanctions might constitute a smart and modern response to Italian and Japanese aggression. He instructed Secretary of the Treasury Morgenthau to ascertain what authority the president had to seize Japanese assets and hold them against payment of damages. 37 Morgenthau consulted his senior legal advisor, General Counsel Herman Oliphant, and reported the next day that a 1933 amendment to the Trading with the Enemy Act empowered the president to issue regulations that prohibited or restricted exchange transactions if the president declared a national emergency. FDR was delighted and instructed Morgenthau to develop the concept further.

General Counsel Oliphant put the Treasury Department’s top lawyers through their paces, directing them to complete a draft legal justification of the concept as quickly as possible. 38 ] Assistant Secretary of Treasury Wayne Taylor pushed for more deliberation during a departmental review, asking under what circumstances the United States could impose the rules and for how long. Morgenthau remarked that those decisions would be up to the president, with restrictions removed when the Japanese agreed to “be good boys.” When Taylor argued that the proposed regulations might lead to war, Morgenthau shot back that “they’ve sunk a United States battleship [sic] and killed three people….You going to sit here and wait until you wake up here in the morning and find them in the Philippines, then Hawaii, and then in Panama? Where would you call halt?” Taylor, reflecting the opinion of most Americans, said he would wait quite a while. 39 When Morgenthau snapped that he could see no reason to wait for the Japanese to strike again, Taylor blurted out “Well, of all the cockeyed things in the world that we can do that would be more cockeyed than the last World War we got into, this would be it.” The exchange reveals how extensive isolationism was even within a department headed by one of Roosevelt’s most dynamic, interventionist confidantes. Morgenthau’s reply to Taylor’s outburst sheds insight into the president’s thinking and illustrates how pervasive was the tendency to equate the Panay with the Maine among policy elites, though the latter was far larger and its loss had cost the lives of hundreds. Morgenthau told Taylor:

Well, I’m very sorry but this is what the President wants. Personally, I think it’s a marvelous idea….For us to let them put their swords into our insides and sit there and take it and like it, and not do anything about it, I think is un-American and I think we’ve got to begin to inch in on those boys, and that’s what the President is doing….How long are you going to sit there and let these fellows kill Americans soldiers and sailors and sink our battleships [sic]? 40

One of the major stumbling blocks to the Treasury plan was that Japan might sell or convert its assets before they could be frozen. To render the plan workable, the British would have to be brought onboard. The President directed Morgenthau to contact Sir John Simon, Chancellor of the Exchequer, directly, bypassing the usual diplomatic channels and keeping the matter as secret as possible. 41 The British response was cautious, and by the time Treasury had completed drafting the regulations on 21 December, Roosevelt had cooled toward the proposal. Without British cooperation, the economic instrument of power was blunt and difficult to deploy.

Roosevelt was left to rely on diplomatic negotiations to resolve the crisis. Secretary of State Hull had always believed that dealing with the crisis diplomatically was the only option given the strength of isolationist sentiment in Congress, and FDR had resorted to backchannels to explore possible naval and economic responses to the Panay’s sinking. But resolving the crisis through non-coercive diplomacy required Japanese cooperation. There was considerable anxiety in the White House, at the State Department, and at the American embassy in Tokyo that the Japanese might fail to respond appropriately. This sense of anxiety mounted as the administration received information that undermined the initial Japanese narrative of an accidental attack under conditions of restricted visibility. On the 16th, Secretary of State Hull directed Ambassador Grew in Tokyo to call upon the Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs as soon as possible. Grew was to tell the Hirota that the American government had received disturbing new details concerning the attack. Particularly troubling were reports that while survivors were escaping the sinking Panay, Japanese airplanes had dived and strafed its lifeboats at extremely low altitudes. Hull concluded that these new reports raised two questions. How did Tokyo intend to deal with those responsible for the incident? And what specific steps would the Japanese take to ensure that American nationals, interests, and property in China would not be subjected to further attacks or unlawful interference from Japanese forces and authorities? 42

Japanese Ambassador Hirosi Saito waiting to see Secretary of State Hull to express regrets, December 13th, 1937 (LOC Image #LC-DIG-hec-23766)

The following day, matters threatened to boil over when the Japanese ambassador called upon the Secretary of State to deny that the Panay or any of its survivors had been fired upon by Japanese military boats with machine guns. Hull interrupted him, insisting that the American government had incontrovertible proof to that effect. Turning to the matter of punishment, Hull lectured the Japanese ambassador that “if Army or Navy officials in this country were to act as the Japanese had over there, our Government would quickly court martial and shoot them.” 43 In Tokyo, Ambassador Grew wrote in his diary on the 20th December that as evidence began to mount that the attack may have been deliberate, “My first thought was that this might result in a breach of diplomatic relations and that Saito [Japan’s ambassador to the United States] would be given his passports and that I would be recalled home, for I ‘remembered the Maine.’” 44

Had the Japanese government dug in its heels and argued that the American government had only itself to blame for putting the Panay into a dangerous situation – as a number of isolationists in the United States were doing – Grew’s fears of a diplomatic rupture might have materialized. Instead, on December 15, Vice Minister of the Navy Isoroku Yamamoto informed the American ambassador that he had relieved Rear Admiral Teizo Mitsunami, commanding officer of naval air forces in the Shanghai region, of command. The next day, Japan’s Navy Minister announced that the Imperial Navy would render a salute of honor to the victims of Panay at the site of the attack. In addition, he extended the apologies of every member of the Japanese Navy to the US Navy. The Japanese government moved quickly to share the information it had received from the investigations it had initiated. Indicative of the serious inter-service rivalries that plagued Japan during this period and throughout the Second World War, the Japanese government was never able to fully reconcile the conflicting reports it received from the Army and Navy. 45 Nonetheless, a high level Japanese delegation, led by Vice Minister of the Navy Yamamoto [who in 1941 as Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet would plan the Pearl Harbor attack] spent three hours on the evening of December 23rd briefing Ambassador Grew and his team on the Japanese investigations. Grew reported to Washington that the effort had been thorough, with maps strewn all over his office. All the American attendees, Grew noted, had been impressed “with the apparently genuine desire and effort of both [the Japanese] Army and Navy to get at the undistorted facts.” 46

Grew had not yet received a copy of US Naval Court of Inquiry findings when the Japanese presented their briefings, and he told them that based on the information he possessed, the Japanese account did not tally completely with the evidence. Grew reminded his high-level visitors that the American government was still waiting for a full reply to two American notes (December 14th and 17th) demanding that Japan express regret, offer full compensation, and provide assurances, and to Hull’s follow-on note reiterating these points and inquiring how Tokyo would deal with those responsible. 47

The next day, the Japanese Foreign Minister handed Grew his government’s official response. The Japanese note maintained that the incident had been “entirely due to a mistake,” and explained that thorough investigations had fully established that the attack had been “entirely unintentional.” The Japanese note reaffirmed Japan’s deep regret and willingness to pay indemnities, adding that the Japanese Navy had been issued strict orders to “exercise the greatest caution in every area where warships and other vessels of America or any other third power are present, in order to avoid a recurrence of a similar mistake, even at the sacrifice of a strategic advantage in attacking Chinese troops.” Furthermore, Hirota continued, the commander of the flying force concerned had been removed from his post for failing to take the fullest precautions. Staff officers, the commander of the flying squadron, and all others responsible for the attack would be duly dealt with according to law. 48

By the time Washington received the note at noon on Christmas evening, the administration was digesting the State Department’s preliminary report on the bombing of the Panay and US Naval Court of Inquiry findings. 49 Both were damning, leaving little doubt that the Panay’s survivors felt the attack had been deliberate. A senior US diplomat embarked on the Panay, commented that he and the other survivors had “every reason to believe that the Japanese were searching for us to destroy the witnesses to the bombing.” The Navy report did not speculate on Japanese intentions, confining itself to listing 36 findings of fact. These spoke for themselves, in particular the finding that a Japanese powerboat filled with armed Japanese soldiers had approached close to the Panay, opened fire with a machine gun, and boarded the vessel after the air attacks had subsided. Contradicting the Japanese investigations, the US navy court of inquiry concluded, “it was utterly inconceivable that the six light bombing planes coming within about six hundred feet of the ships and attacking for over a period of twenty minutes could not be aware of the identity of the ships they were attacking.”

The State Department report and the findings of the Naval Court of Inquiry made it difficult for the administration to accept the Japanese position that the entire incident had been accidental. They were uncertain, however, whether the Japanese government was itself directly responsible, or whether “wild, runaway, half-insane Army and Navy officials” in China had initiated the attack. 50 The American ambassador in Tokyo believed that the Japanese Army and Navy were “running amok, and perpetrating atrocities which the Emperor himself cannot possibly desire or sanction.” 51 As for the Japanese government, it had substantially met the four demands FDR and Hull had communicated. The Japanese government had expressed its regret. It had indicated that it stood ready to pay damages. It was providing assurances that it was putting restrictions on its forces so as to prevent any repetition of similar incidents in the future. Lastly, the Japanese took the unusual step of removing a commander and reprimanding his subordinates. Given that he had no proof that the Japanese government had instigated the attack, the president decided to settle the matter. On the afternoon of Christmas Day, Hull sent a note to Tokyo indicating that the United States regarded the Japanese note as “responsive” to American requests.

When Grew, the American ambassador in Japan, communicated the American acceptance of the Japanese note to Foreign Minister Hirota, he recorded that Hirota’s eyes filled with tears. The Foreign Minister remarked to Grew that “I heartily thank your Government and you yourself for this decision. I am very, very happy. You have brought me a splendid Christmas present.” 52 The Panay crisis was over.

Norman Alley describing his experiences to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Charles Edison following the screening of footage of the Panay attack, 31 December 1937 (LOC Image #LC-DIG-hec-23823)

We didn’t get the satisfactory apology from Japan that we asked for… In its note Japan distinctly negatived [sic] any charge of responsibility for other than an unpremeditated incident. This we have accepted, despite the fact that we know, and are apparently in a position to prove, that the attack was deliberate and wanton. It may be that the President thinks public opinion would not support him if he should go any further just now, but he proposes to be ready if another incident occurs….Much as I deprecate war, I still think that if we are ever going to fight Japan, and it looks to me as if we would have to do so sooner or later, the best time is now. 54

A number of accounts have suggested that the Panay crisis brought the United States to the brink of war with Japan four years before Pearl Harbor. 55 Despite the rumblings of Ickes, Swanson, Leahy, and others, this is an overstatement. 56 The president pushed his advisors to give him a range of options, asking Morgenthau to look into the legality of seizing Japanese assets and directing Leahy to initiate conversations with the British Admiralty. Yet Roosevelt was keenly aware of public and Congressional opinion, telling a friend after the hostile reaction to his “Quarantine Speech” the previous October that “It’s a terrible thing to look over your shoulder when you are trying to lead and find no one there.” 57

Secretary of State Hull captured the administration’s assessment of the situation in the memoir he published ten years after the event. Drawing upon memoranda, conversations, and his recollections, Hull characterized Japanese claims that the incident was entirely accidental as “the lamest of lame excuses.” Elaborating, he explained

That some members of the Foreign Office had no hand in it may be true. Hirota himself professed to be genuinely disturbed and sincerely regretful. That the Japanese people did not like it also seemed to be true, to judge from the thousands who expressed their sympathy to the Embassy and offered contributions for the families of the victims and for the survivors. But that the Japanese military leaders, at least in China, were connected with it, there can be little or no doubt. In any case, it was their business to keep their subordinates under control. 58

Continuing, Hull explained, “On this side our people generally took the incident calmly. There were a few demands that the Fleet should be sent at once to the Orient. There were many more demands that we should withdraw completely from China… It was a serious incident; but, unless we could have proven the complicity of the Japanese Government itself, it was not an occasion for war.” 59

(Return to September 2018 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

- The original chart, with Arthur “Tex” Anders’ penciled orders and blood drops, is exhibited at the US Naval Academy Museum. ↩

- For a full account, see Douglas Peifer, Choosing War. Presidential Decisions in the Maine, Lusitania, and Panay Incidents (New York; Oxford UK: Oxford University Press, 2016). ↩

- The Commander in Chief of the United States Asiatic Fleet (Yarnell), et al., to the Commander of the Japanese Third Battle Fleet at Shanghai, 22 August 1937, Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, Japan: 1931-1941, vol. 1, 487-88. Henceforth FRUS Japan 1931-41. A naval inquiry later concluded that the shell which landed in the well-deck where the crew had assembled to watch a movie was a Chinese anti-aircraft shell, but at the time Yarnell believed it was Japanese, with FDR informed that the AA shell was probably fired by the Japanese. Harold L. Ickes, The Secret Diary of Harold L. Ickes: The inside Struggle 1936-1939 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1954), 199. ↩

- In a response to a Senate request for information, Secretary of State Wells provided a detailed listing of US troops, naval vessels, and military supplies in the Far East at the close of 1937. The US sent an additional 1500 Marines to Shanghai in the summer of 1937. See Secretary of State to Senator Ernest Lundeen, 27 December 1937, FRUS 1937, vol.4, 420-22. ↩

- Secretary of State to the Ambassador in China, August 10, 1937, FRUS 1937, vol.4, 252-3. ↩

- The Secretary of State to the Ambassador in Japan (Grew), 30 August 1937; Aide-mémoire from the American Embassy in Japan to the Japanese ministry for Foreign Affairs, 1 September 1937. FRUS Japan 1931-41, 491, 494-5. ↩

- The American Ambassador in Japan to the Japanese Minister for Foreign Affairs, September 17, 1937 and Memorandum by the Ambassador in Japan (Grew), 20 September 1937 in FRUS Japan 1931-41, 498-501; Joseph C. Grew, Ten Years in Japan: A Contemporary Record Drawn from the Diaries and Private and Official Papers of Joseph G. Grew, United States Ambassador to Japan, 1932-1942 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1944), (entry 20 September 1937), 217. ↩

- Ibid., 217-18. ↩

- Cordell Hull and Andrew Henry Thomas Berding, The Memoirs of Cordell Hull (New York: Macmillan Co., 1948), 566. ↩

- Secretary of State Hull’s first reaction to the widening conflict touched off by a clash between Chinese and Japanese troops at the Marco Polo Bridge on 7 July was to issue a formal statement – the “Eight Pillars of Peace Program” – advocating national and international self-restraint; the abstinence by all nations from the use of force; the adjustment of problems through peaceful negotiations; the faithful observance of international agreements; respect by all nations for the rights of others; and the revitalizing and strengthening international law. Hull claimed that these doctrines were “as vital in international relations as the Ten Commandments in personal relations,” but they were idealistic statements of aspiration rather than realistic policy responses to the challenges posed by the Japanese, Italians, and Germans. “Statement of the Secretary of State,” 16 July 1937 in FRUS, 1937, vol.1, 699-700; ibid., 535-36. ↩

- Description of cabinet sessions of 7 and 13 August, 1937, from Harold Ickes, The Inside Struggle 1936-1939 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1954), 186, 92-3. ↩

- John Morton Blum, From the Morgenthau Diaries. Years of Crisis, 1928-1938 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1959), 481. ↩

- Congressional Record, 75th Congress, 1st session, 24 July & 3 Aug 1937, p.8156, 10442. ↩

- Dorothy Borg, The United States and the Far Eastern Crisis of 1933-1938; from the Manchurian Incident through the Initial Stage of the Undeclared Sino-Japanese War (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1964), 320-21. ↩

- Borg, The United States and the Far Eastern Crisis of 1933-1938; 325. ↩

- Henry Hitch Adams, Witness to Power: The Life of Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1985), 98. ↩

- Policy statement of the Commander in Chief of the United States Asiatic Fleet, 22 September, Memorandum by the Secretary of State to President Roosevelt, 4 October FRUS 1937, vol.4, 352-3, 363-64. ↩

- Diary entry September 19th, 1937, Ickes, The Inside Struggle 1936-1939, 209. ↩

- Hull and Berding, The Memoirs of Cordell Hull, 557. For examples of impeachment threats, see the cable that Representative George Holden Tinkham, R- Massachusetts, sent Cordell Hull on 13 Oct and the statement by Hamilton Fish, R- New York, New York Times, 14 October, 1937: 16 and 17 October, 1937: 40. ↩

- Political Quarterly, October – December, 1937, from H. W. Brands, What America Owes the World : The Struggle for the Soul of Foreign Policy (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 125. ↩

- Ibid., 126. ↩

- New York Times, Oct 14, 1937, p. 16. ↩

- Ickes, The Inside Struggle 1936-1939, 211. ↩

- Ambassador in Japan to Secretary of State, 945 pm 13 December 1937, Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States [henceforth FRUS ↩

- Ambassador in Japan to Secretary of State, 3 pm 13 December 1937, FRUS Japan 1931-41, 521-22. ↩

- Yarnell to Leahy, and Bemis (Naval Attaché in Japan) to Leahy, 13 December, FRUS, 1937, vol. 4, 492-3. ↩

- Hull and Berding, The Memoirs of Cordell Hull, 560. ↩

- Leahy and his wife were dining with the Woodrings (Harry H. Woodring was Secretary of War) when he received word of the incident. Leahy excused himself in order to join the small group that Secretary of State Hull had convened for discussions late Sunday evening at his Carlton Hotel apartment. Adams, Witness to Power: The Life of Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, 101. ↩

- Ibid., 274. ↩

- Henry Hitch Adams, Witness to Power: The Life of Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1985), 101. ↩

- The concept, as FDR explained to the cabinet, entailed the US Navy blockading Japan from the Aleutian Islands to Hawaii, to Howland, to Wake, to Guam while the Royal Navy would take over from Guam to Singapore. Ickes, The Inside Struggle 1936-1939, 274-75; William D. Leahy, I Was There; the Personal Story of the Chief of Staff to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman, Based on His Notes and Diaries Made at the Time (New York: Whittlesey House, 1950), 64, 128-29; Adams, Witness to Power: The Life of Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, 101-2. ↩

- The Chargé in the United Kingdom (Johnson) to the Secretary of State, December 13, 1937. FRUS 1937, vol.4, 490-91. ↩

- Ibid., 494-95. ↩

- Memorandum by the Secretary of State on conversation with the Ambassador of Great Britain, 14 December 1937, in FRUS 1937, vol.4, 499-500. ↩

- Lawrence Pratt, “Anglo-American Naval Conversations on the Far East of January 1938,” International Affairs 47, no. October (1972), 752. ↩

- For details of the secretive talks between Captain Royal E. Ingersoll, USN, Chief of War Plans Division, and Captain Tom Phillips, his Royal Navy counterpart, see Royal E. Ingersoll, interview by John T Mason Jr.1964, Wasington D.C; Alan Harris Bath, Tracking the Axis Enemy: The Triumph of Anglo-American Naval Intelligence, Modern War Studies (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1998), 14-16; Gregory J. Florence, Courting a Reluctant Ally: An Evaluation of U.S./Uk Naval Intelligence Cooperation, 1935-1941 (Washington, D.C.: Center for Stategic Intelligence Research, Joint Military Intelligence College, 2004), 30-34; Pratt, “Anglo-American Naval Conversations,” 745-63. ↩

- Robert Dallek, Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932-1945: With a New Afterword (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 154; John Morton Blum, From the Morgenthau Diaries. Years of Crisis, 1928-1938 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1959), 486. ↩

- For an account of the development of the concept which would lead to the establishment of the Foreign Funds Control office of the Treasury Department on April 10, 1940, see by Richard D. McKinzie’s interview of Bernard Bernstein on July 23, 1975, available online as Oral History project at the Truman Library, at http://www.trumanlibrary.org/oralhist/bernsten.htm [accessed 16 August 2017 ↩

- Blum, From the Morgenthau Diaries. Years of Crisis, 1928-1938, 487. ↩

- Morgenthau recalled that the president had pulled out Oliphant’s memorandum and told the cabinet that “We want these powers to be used to prevent war… After all, if Italy and Japan have evolved a technique of fighting without declaring war, why can’t we develop a similar one.” Ibid., 488-89. ↩

- Borg, The United States and the Far Eastern Crisis of 1933-1938; from the Manchurian Incident through the Initial Stage of the Undeclared Sino-Japanese War, 495. ↩

- Secretary of State to the Ambassador in Japan, 16 December 1937, FRUS 1931-41, vol.1, 527. ↩

- Memorandum by the Secretary of State re discussion with Japanese Ambassador, 17 December 1937, FRUS 1931-41, vol.1, 529. ↩

- Diary entry 20 December 1937, Joseph C. Grew, Ten Years in Japan: A Contemporary Record Drawn from the Diaries and Private and Official Papers of Joseph G. Grew, United States Ambassador to Japan, 1932-1942 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1944), 235.

One might note that the Japanese Foreign Ministry was cognizant and alarmed by initial press references in the United States referencing the Maine. See cable from Tokyo to the Japanese Embassy in Washington, 17 December, in National Archives, RG 457, Entry 9032 (HCC), Box 751, Folder 1916, Translations of Japanese Messages Re: Panay Incident. ↩

- For specifics on the Japanese Kondo (Navy), Takada (Navy), Harada (Army), and Nishi (Army) investigations, see Manny T. Koginos, The Panay Incident; Prelude to War (Lafayette: Purdue University Studies, 1967), 66-71; Harlan Swanson, “The Panay Incident: Prelude to Pearl Harbor,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 93, no. 12 (1967). ↩

- The Ambassador in Japan (Grew) to the Secretary of State, 23 December 1937, FRUS 1931-41, vol.1, 547-48. Grew provides an account of the briefing in his diary as well, but places the meeting on the 22nd December. Grew, Ten Years in Japan, 237-39. ↩

- One has to take note of the time difference between Tokyo and Washington. Instructions dispatched from Washington on the afternoon of the 13th and 16th December would be received and acted upon in Tokyo on the 14th and 17th December. ↩

- Copy of Japanese note sent from Grew to the Secretary of State, 24 December 1937, FRUS 1931-41, vol.1, 549-550. ↩

- The findings of fact of the US Naval Court of Inquiry, along with George Atcheson Jr.’s detailed report to the Secretary of State, are available at FRUS, 1931-1952, vol.1, 532-547. ↩

- Memorandum of the Secretary of State, 17 December 1937, FRUS 1931-1941, vol.1, 529. ↩

- Diary entry, 20 December 1937. Grew, Ten Years in Japan, 236. ↩

- Ibid., 240. ↩

- Hamilton Darby Perry claims that Alley was asked to cut out about 30 feet of film that showed low level attacks on the Panay, presumably because the footage might undercut the diplomatic settlement just reached. Perry indicates that Alley showed him the missing footage, with the story picked up by Kenneth Davis among others. Alley’s 1941 memoir makes no mention of any missing footage, and Universal Studies claimed that the film it ran was “Uncensored!!! Unedited!!!” Hamilton Darby Perry, The Panay Incident; Prelude to Pearl Harbor (New York: Macmillan, 1969), 231-232; Kenneth Sydney Davis, FDR. Into the Storm, 1937-1940 (New York: Random House, 1993), 158; Norman Alley, I Witness (New York: W. Funk, 1941), 284-86.The full clip which ran in theaters is available at the Universal Studies archive at the Internet Archive, Universal Newsreels, at https://archive.org/details/1937-12-12_Bombing_of_USS_Panay [accessed 16 August 2017 ↩

- Ickes, The inside Struggle 1936-1939, 279. ↩

- William L. Langer and S. Everett Gleason, The Challenge to Isolation, the World Crisis, and American Foreign Policy 1937-1940 (Gloucester, Mass.: Peter Smith, 1970); Harlan Swanson, “The Panay Incident: Prelude to Pearl Harbor,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 93, no. 12 (1967): 27-37. ↩

- Borg, who has written the most detailed examination into FDR’s Far Eastern policy during this period concludes that the president never seriously considered going to war of the matter. Borg, The United States and the Far Eastern Crisis of 1933-1938, 501-3. ↩

- Davis, FDR. Into the Storm, 1937-1940, 135. ↩

- Hull and Berding, The Memoirs of Cordell Hull, 563. ↩

- Ibid. ↩