Karen J. Johnson

U.S. Courts Library

Libraries are wonderful places, as most are aware, but there are different kinds of libraries, and I would wager that a researcher of naval history would not necessarily think of a court library or a court librarian as a source for their research or a research topic, at least not initially. Me either, if truth be told.

It was by chance that our library, the U.S. Courts Library in Norfolk, Virginia, even became a small repository of archival items. The primary function of court libraries is to serve the research needs of the judges and their staff. However, many court librarians also become court historians. Not long after our library first opened, a local attorney donated his father’s copy of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, a small book by comparison to today’s handbook. The small gift’s importance and special place in Norfolk’s court history remained unremarked for decades. We now know that the book is one of the first handbooks published after the standardization of the rules in 1932. This donation sparked an interest in early American legal and court history, that researcher’s Pandora’s box we all know so well. The more I researched, the more questions I had and paths to follow. My co-worker, Library Technician, Mary M. Russo, now retired, helped put some of my finds on paper including the story you will read below.

As time went on, as the role of the library was evolving into the repository for the court’s history, so too, more artifacts and files and records were donated, and some were even found by exploring forgotten cabinets, boxes, and rooms in the courthouse basement. It was so much fun!

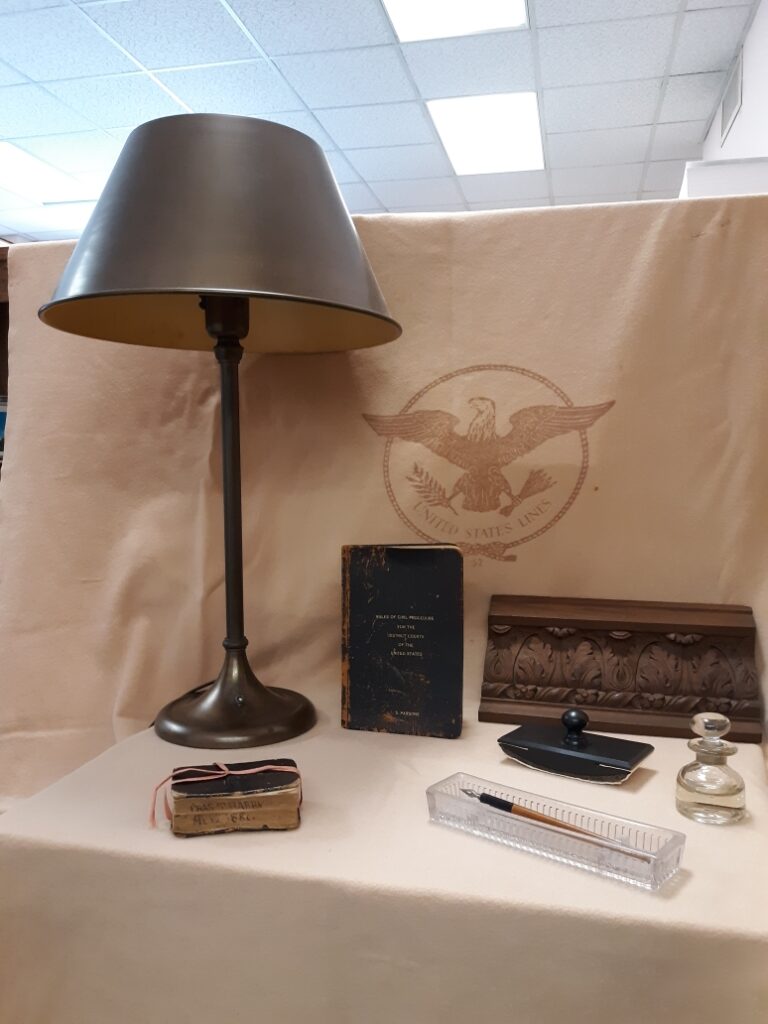

Beautiful antique furniture, rare and unique books of the court, architectural models, lamps, an old pen and inkwell, and photographs are now part of our historical collection.

Records and files that are now part of the collection include a variety of court-related documents. If you look through the material you’ll find resolutions from the 1930s and 1940s memorializing judges, lawyers, and others who held roles in the court – even a librarian who previously worked for a federal judge before going on to read law and becoming the bar library director. There are court papers from the early 1800s – from a case involving a ship seized by the Chesapeake that was smuggling slaves- and papers from a handful of admiralty prize cases.

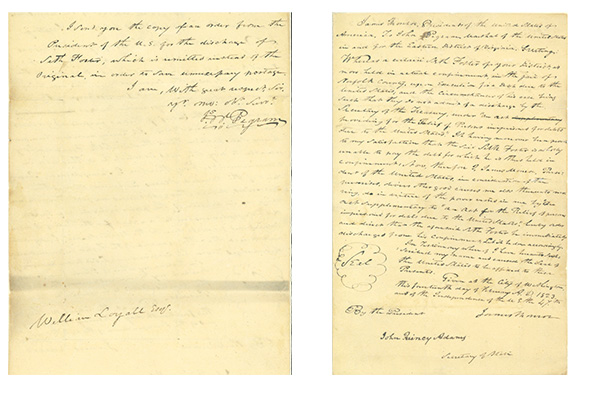

In the file of one of the prize cases, I found a highly curious document. The file contained a letter dated February 20, 1823, with a copy of an order from the President of the United States, James Monroe, instructing the Deputy U.S. Marshal to “immediately discharge from his confinement” Seth Foster, U.S. District Court Clerk, for the court at Norfolk. Foster was the court’s first Clerk of Court and remains the court’s longest-serving Clerk of Court to date. His offense; money owed to the United States that had gone missing from the sale of the Brig Transfer. Despite the assessment of Foster’s responsibility for the missing funds and his obvious confinement, Foster remained court clerk, while in jail, and for another thirteen years afterwards. His story reflects the issues of the day and brings forward a time of great hardship in Norfolk.

Seth Foster’s life story reads like an 18th-century novel, but instead of rags to riches, his story goes from riches to rags. Personalities in the story include Cyrus Griffin, first judge of the court-appointed by George Washington; another famous judge of the court, St. George Tucker; and even President of the United States James Monroe. Events range from an honored position to a hell-hole of prison, from misappropriation of funds to restoration of honor. And, I was obsessed to learn his story. It took several years of searching, contacting historians and archives to pull together Foster’s story and to bring to light a little-known case in our naval history, a story that really was not all that uncommon in the early days of our country.

According to his obituary, Foster was born in Boston around 1757. How and when he came to Norfolk is unknown, but he first appeared as an alderman for the borough and commissioner for the local court in 1795. In June of that year, he assumed the one-year term as mayor. When that term was finished, he returned to the council, then served again as mayor from June 1800 until May 1801, when he resigned to assume the position of the first Clerk of Court for the U.S. District Court in Norfolk at the request of Cyrus Griffin, the first federal judge commissioned in Virginia. Although federal courts were created by the first Judiciary Act in 1789, it was not until 1801 that the district court was moved from Williamsburg to Norfolk. District courts had limited jurisdiction at the time, but importantly, district courts heard admiralty cases. Norfolk was the Commonwealth’s primary port.

On August 7, 1785, records show that he was married to Ann Starke King, widow of John King, a merchant of Hampton, and the daughter of Bolling Starke, a wealthy landowner, politician and descendent of Pocahontas, and Elizabeth Belfield of Dinwiddie County. Foster and Ann were the parents of three sons, William P. Foster, who became a deputy marshal of the court in Norfolk around 1813; Winslow Foster, who, in 1822, was commander of the revenue cutter Alabama; and Seth Belfield Foster, a doctor, who served as deputy court clerk for a few years before relocating to West Virginia.

How and where Foster received his education remains unknown, based on the sources at my disposal, but he was qualified to act as a lawyer before the court, and over his many years as clerk Foster served as an appraiser, a commissioner, a crier, and a registrar.

According to notations by Virginia biographer, S. Bassett French, Seth Foster was one of the wealthiest men in Norfolk. “He was a man of the old school of very refined and polished manners,” French wrote “… honored and cherished for his Virtues.” 1 He was a staunch Federalist, a trait he shared with Cyrus Griffin who chose him to be clerk in Norfolk. Foster’s elegant hand recorded court documents under five succeeding judges of the court. He was one of the last of the queues in Norfolk, wearing a long plait of hair down his back. 2

Foster’s troubles have their root in an admiralty prize case that comes into the court in June of 1805. Charles Stewart, naval hero of the Early American era, captured The Brig Transfer in March 1804 during the Barbary War. Commodore Edward Preble, in charge of the blockade of the harbor at Tripoli, added additional guns to the brig and used her to patrol the harbor. Valued at the time of her capture at $5,000, she apparently deteriorated quickly, and in 1805 U.S. Naval personnel, led by Lt. Ralph Izard, Jr. brought her in the Norfolk harbor. With the case pending in the district court, Judge Cyrus Griffin ordered the ship sold before further deterioration made her worthless. She was sold at auction, and in July 1805, Foster received $611.30, the amount remaining after deduction of all fees and charges related to the sale. He received the money from Cary Selden, deputy U. S. Marshal, with instructions to deposit it in the Bank of the United States. The historical record proves that Foster carried out the deposit.

The sale had no impact on the case at issue. Complicated legal issues in the awarding of this prize led the court judge to hold over the case. The last entry in the order book for 1805 states that the case is to be held over “due to reasons of great importance to the United States of America.” 3 The succeeding order book has been lost, and we do not see reference to the case again until 1809 when an order was entered for distribution of the proceeds to the crew who captured it. Despite the order, final awarding of the prize faced further delays and did not emerge until 1817 when the U.S. Congress awarded $2,500 to be shared by the estates of Preble, Stewart, and others in the crew.

The decision to place the money in the Bank of the United States proved problematic. The money received by Foster remained in the Bank of the United States until 1811, and, one would think would be secure. However, the Bank required Congress to renew the operating charter every 20 years. Congress refused to renew the bank’s charter and the bank closed. At this time, Foster wrote a letter to the Secretary of the Navy asking what he should do with the money. 4

Financial instability hit Foster personally around the same time. Jefferson’s embargo in 1809, followed by the War of 1812, merchants up and down the coast of the United States suffered losses. In May 1814, Foster wrote a letter to Moses Myers, a local merchant also in dire straits, apologizing for a past due account. 5 Foster and Myers joined thousands of others in the reversal of fortune they endured. One by one, many saw their fortunes vanish. The once busy wharves of Norfolk grew silent. One bleak Monday morning when District Attorney William Wirt was in town for the May 1817 term, he wrote a letter home to his wife about the changed city of Norfolk and her people:

There is an air of sadness over this place which depresses me extremely. It is no longer the animated, bustling place we knew in 1805-6. I thought it possible at first that it was … the knowledge of the fact that the society once so social and harmonious here had been chilled and seared [sic] by personal finds that imparted this changed and melancholy appearance to the place. But I see very plainly that all that commercial prosperity which gave gaiety and spirit of good humor to the town is almost extinguished if not entirely gone. The port is no longer crowded with ships, nor the wharves loaded with crates and bales of freshly landed goods, nor the market square and streets filled with drays, carts, wheelbarrows and noisy porters. The people of the town themselves confess the sad change and seem to think that Norfolk has received its death blow in the late war. Yet enough of their habits both of business and of hospitality remains to remind me of what the place was twelve years ago, and to make me feel the change affectingly. The merchants and the sailor wives still come down to the end of the street to look out for some expected ship. 6

On November 16, 1819, fourteen years after the sale of the Brig Transfer, the order book of the court recorded the case U.S. v. Seth Foster, a “rule to shew cause.” Foster was ordered to appear in court on the first day of the next term (May 1820) to explain what happened to the missing $611.30, equivalent to over $10,000 today. The following day, the court ordered Foster to supply the court with a list of all processes served by his son, William P. Foster, a former deputy marshal, to include the amount of fees not collected, and a list of the allowances made to William for the custody and safe keeping of vessels. 7 Was this order related to the missing money? No answer appeared and no connection became clear. A later court case showed that William had collected fees and assessments from local citizens, but he failed to account for and pay the amounts to the United States. 8 By 1819, William no longer resided in Norfolk. Seth Foster, the father, remained Norfolk to face the court.

The winter that passed was surely one of great anguish for Seth and Ann Foster. They had lost everything and been subjected to public disgrace. When the court convened on May 13, 1820, U.S. District Judge St. George Tucker, receiving no reasonable explanation from Foster, ordered that an attachment be issued against him for his contempt in not complying with the order on November 16, 1819. Two years passed. At the court session of May 6, 1822, Tucker noted that Foster had neither deposited the money nor issued the ordered attachment. A motion was filed by the United States Attorney, Robert Stanard, to enforce obedience by August 1.

On August 1, 1822, Deputy Marshal William Loyall took Foster into custody. He was to be held at the jail in Norfolk, “with the benefit of the prison rules.” 3 That meant that Foster would be allowed to leave the jail each morning to go to his work, but he had to return to the jail each night. Jails of that time period were foul and putrid places, where diseases ran rampant. Benefit of the prison rules meant that for at least part of the day, the prisoner enjoyed healthier surroundings. In early November of that year, the U.S. Attorney requested the court to withdraw the benefit of the prison rules, a harsh step that would restrict Foster to the jail with little hope of redemption. Tucker denied the motion, giving Foster one more chance to repay the money.

On November 23, 1822, Foster wrote a heart-rending petition to President James Monroe, the only person who could grant him clemency. Foster told Monroe that at the age of 65, he was elderly and had an elderly wife to support. He was penniless, and his assets consisted of nothing exceeding $30. He did not explain the lost money, but declared that in his long years of service to the United States he had accounted for every penny placed in his trust for the government of the United States – except for the $611.30 in question. 10 Through it all, Foster remained Clerk of the Court and recorded these events. In February 1823, an order of discharge came down from President Monroe, the same one in the court files today. He had investigated Foster’s claim, and finding no malice, Monroe used a law passed in 1817 for the relief of debtors to order that Seth Foster be released from prison. 11 On March 5, 1823, Foster walked out of the jail adjacent to the Borough of Norfolk Courthouse, the same courthouse where his federal district court met. He emerged as a free man, both free of prison and cleared of debt.

A chastened Foster returned to his work serving the court under Judge Tucker, the very person who put him in jail. His small fees from the clerk’s job appeared to be his only source of money. His beautiful calligraphic handwriting showed signs of tremor as the cases were recorded. In his final years, a young lawyer named George Conway helped him to fulfill his duties. He died on June 14, 1836. The following notice appeared in the local newspaper:

Died, Yesterday morning about sun-rise, in his 80th year, SETH FOSTER, Esq. Clerk of the U.S. Court of this district. Mr. F. was a native of the city of Boston, but had for many years resided in this town, and formerly filled the offices of an Alderman and Mayor. He not only made a profession of religion, but, by his conduct in life, for the last sixteen or eighteen years, gave proof of his having been with Jesus. 12

Foster’s funeral was held the following morning at the Methodist Protestant Church on Fenchurch Street. His eulogy, likely presented by his longtime friend and benefactor, Rev. J. French. Foster died penniless and most probably was buried in the Cedar Grove Cemetery in Norfolk established in 1825. Rev. French had a large plot in the cemetery, and it is known that there were eight more burials on that plot in addition to those of Rev. French and his stepdaughter, the only two recorded burials. Perhaps that was also the last resting place of Seth and Ann Foster. A fire destroyed cemetery records in the early 1900s, leaving researchers to make a best guess.

A final note to Foster’s story involves an unexpected visit to the U.S. Courts Library over 150 years after Foster’s death. I think as researchers we are connectors – we connect to the past, we connect with other researchers, we connect with people who have a shared interest; but to connect a man with his past, his ancestry, was not something I could have foreseen. I think that’s the real reason why Foster’s story came to the Library, why Foster presented himself to me over the years. It was my honor to have been a part, a connector. A few years ago, on my birthday, I received a call from the Slover Library’s Sargeant Memorial Room, a marvelous local history collection which I hope all of IJNH’s researchers take the time to investigate. The archivist said to me, “Karen, I’m sending a man over to see you. You will want to talk with him!” And what a gift to spend the day with Seth Foster’s great, great, great, great, great-grandson. He had come to Norfolk from Norway on a quest to find information about his family! I had a lot to share.

(Return to May 2021 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

- S. Bassett French, Biographical Sketches. Library of Virginia. ↩

- Hugh Blair Grigsby, Discourse on the Life and Character of the Hon. Littleton Waller Tazewell 38 (1860). ↩

- U.S. District Court Order Book, 1819-1850, August 1, 1822. ↩

- Seth Foster to the Honorable Paul Hamilton, Secretary of the Navy, January 29, 1811. Record Group 233, Records of the House Committee of Naval Affairs, 15th Congress, National Archives and Records Administration. ↩

- Seth Foster to Moses Myers, May 26, 1814. Chrysler Museum. ↩

- William Wirt to Elizabeth Wirt, May 5, 1817. William Wirt Papers, Maryland Historical Society, MS1011, Reel #3, 1815-1820. ↩

- U.S. District Court Order Book, 1811-1819, November 17, 1819. ↩

- U.S. v. Moore, 26 Fed. Cas. 1301 (C.C.D. Va. 1828). ↩

- U.S. District Court Order Book, 1819-1850, August 1, 1822. ↩

- Petition of Seth Foster, November 23, 1822. Record Group 59, Petition for Pardons, File 651, National Archives and Records Administration. ↩

- Act of March 3, 1817, ch. 114, 3 Stat. 399. ↩

- American Beacon and Norfolk and Portsmouth Daily Advertiser, June 15, 1836, p. 3, c. 1. ↩