Michael Vlahos

The Johns Hopkins University

“But there was the glory first.”

Rudyard Kipling, The Light That Failed

The Battle of Jutland ranks among Britain’s most bitter disappointments. What should have been another Glorious First of June was, in the end, worse than defeat. The Grand Fleet had somehow let victory slip from its grasp. German upstarts laid a beat down and got away with it.

British propaganda was the world’s best, yet could not cover the shock. Though twice as strong, in a stand-up fight the Grand Fleet failed to win, and highflying hopes turned to beet-red embarrassment. Britain’s celestial claim to naval mastery was lost. Worse, Jutland presaged Britain’s permanent naval demotion just five years later — at American hands.

Yet Britain had engineered its own fall, by embracing the ceremonial ideal of “decisive battle.” The story arc of its pursuit, from 1805 to 1916, delivered instead a decisive failure of British sea power.

Navy ceremonial is well, yet narrowly, understood. Fleet ritual and symbol are things outside the central naval mission, which is, above all, battle. I argue here for a much broader understanding of naval battle itself: As being driven by ceremony as much as by strictly instrumental needs. At Jutland, at its core, the primary battle mission was ritual and symbolic.

The ceremonial mission of English sea battle was established in national identity during the Elizabethan era, and grew into a fully mature component of the British narrative by the mid-Georgian era. Horatio Nelson, however, took the story kernel much further. In a celebrated series of sea battles, culminating in Trafalgar, he crafted a model of decisive battle that bonded instantly to the populist British national community — a true “United Kingdom” — then emerging. 1

Through the Victorian era, Trafalgar operated as an almost scriptural testament weaving together navy and nation. Alfred Thayer Mahan, however, transformed already mythic narrative into a more urgent teaching. If The Influence of Sea Power Upon History took the world by storm, the Battle of Tsushima made his teachings law. Sea power thus laid a geas (or magical obligation) on the Royal Navy. The next war was already being imagined as Grand Fleet vs. Höchseeflotte.

Hence, in 1914, “England expects” another Trafalgar, another ringing paean to British national destiny. Failure at Jutland was not simply a tactical or strategic failure: It shamed the hopes of ancestors and of history.

This essay follows the story of a prefigured ceremonial battle, as it slowly builds toward Jutland and afterward, unravels: 1) How ceremonial battle evolved, 2) How decisive naval battle was invented, 3) How ceremony took full control, 4) How Admiralty, in the century before 1914, made strategy subordinate to ceremony, and 5) How Navy storytelling after the battle told a bald-faced tale of victory.

How Battle Became an Existential, yet Ceremonial Event

Military ceremony is central to battle, just as war is central to the life of society. In Modernity, war has been a collective rite, renewing national “ties that bind” and the bonds between people and state. War ceremonial serves to reinvest national authority at home and reassert it abroad. Yet realizing all this requires reaching a kind of unitary, “peak” emotion. Here, great battle becomes the experience that — through bloody ritual — creates a collective peak in sacred national narrative. Battle then serves as an icon representing the nation’s shared commitment and sacrifice. Battle is the banner of war’s meaning in the life of the nation.

Peak emotion in war is always most powerfully stoked by the passionate ceremonials surrounding battle. Yet battle ceremony is a much bigger and more enduring franchise than the combat event itself. Battle ceremony extends into both past and future — the hopes and fears of war to come — and the commemoration of battles past. Thus, great battle is ritually celebrated before and after the event, becoming a permanent marker in the national story. Moreover, transforming a bloody clash into a timeless symbol is less like propaganda and more like sacred literature.

The ceremonial cycle surrounding battle in the age of nationalism can in fact be usefully compared to the sacred texts, liturgy, and iconography of religion.

Religious ceremony establishes and renews authority. From classical antiquity through the early modern era, political and ecclesiastical authority was intertwined. Ceremony was central to the authority of (co-dependent) state and church, in terms of its relationship with society. To do its job, ceremony had to be: 1) public, 2) collective 3) repeatable, 4) participatory, and 5) acclamatory.

Furthermore, and critical to its historical persistence, sacred ceremonies must live simultaneously in the past, present, and future. Miraculous, or “peak” moments of the past come alive again, as they are memorialized in the present, and promise rebirth in the future as miracles yet to be.

The rites of modern politics can have all the resonant power of any religious rite: Where the people can publicly affirm their relationship to each other as a nation, thus renewing their sense of belonging, and loyalty to the national enterprise (and the state).

Ceremonials did not change in Modernity, but rather made war even more essential to people and state, and the new ideologies of religious nationalism. The French Revolution and Napoleon pioneered the very template for war’s choreography of nationalism — of course to be realized through the ceremonial framing of “decisive battle.” Today this all seems archaic, an antique term-of-art, narrowly applied as “rapid, decisive operations” in Army doctrine during the 1990s. After all, how can a single engagement be decisive? What do we even mean by “decisive?”

Traditional dogma variously conferred this title according to three criteria: Such a battle 1) terminates the war, 2) annihilates the enemy force (Vernichtungsschlacht), 2 or 3) alters the course of the war. Yet to imagine a great battle as creating heroic new iconography is to see battle as decisive only if it creates a catharsis in national identity and meaning. Here, battle’s iconic significance can be realized only if its sacrificial enactment and continuing celebration serves to renew the nation and bind it together more closely.

Yet what, precisely, is the ceremonial orchestration of battle necessary to make this happen? The ceremonial cycle of “decisive battle” can be divided into three parts: 1) The “before,” of stirring up collective hope and anticipation, 2) The moment of “blood, sweat, and tears,” looking for intrinsic scripting and seamless stage direction, and 3) After-the-battle — as in ritual gatherings, memorials, cemeteries and ossuaries, painting and statuary, stage and screen pageants, and song — all the moveable feasts of memory. Consider these schoolboy examples:

Caesar’s conquest of Gaul was the most celebrated campaign of Antiquity. This status is due entirely to the Divine Julius’ unwavering focus on the organs of ceremonial: 1) The climactic (and exquisitely staged) decisive battle (Alesia), 2) The unforgettable ceremony of his triumph (a processional masque that Romans called a Triumph, and 3) His iron grip on the narrative of his victory and its political significance (De Bello Gallico). 3

In 1624 the Spanish Hapsburg Crown, beleaguered, sought to extricate itself from the quagmire of endless bloodletting in “Flandres.” The solution, 1700 years after Caesar, was to duplicate his orchestration of battle ceremonial. The siege of Breda followed, almost precisely, Caesar’s victory script. At its successful conclusion, however, instead of a triumph and a book, Phillip IV tasked Diego Velasquez with a grand canvas of the surrender. The mastery of court painters brings us the ritual of victory not only as a decisive moment, but also as an icon of magnanimity, and thus, subtly, of Spain’s grandeur: Where the exquisite moment of triumph lives forever. 4

Closer to living memory, Comrade Stalin followed this playbook at Stalingrad: The man of steel would rescue the city of steel. Because the city of steel, the immovable object, stopped dead the unstoppable force (the Wehrmacht), the relief of the city was the prefiguration of salvation for the Soviet Union itself, while the wretched procession of the Sixth Army — 90,000 scarecrows staggering to their final Gulag — was the razor counterpoint to Spanish magnanimity at Breda.

Decisive battle as a template event has been in play for millennia. American history is a parade of such sacred happenings, culminating in D-Day, when the United States annually consecrates its liturgy to the world.

Naval battles too have transformed into a national mass: Tsushima and Operation AI for Japan, Midway for the U.S.A., Lepanto for Hapsburg dynasts and the Holy See, and above all, for Britain, Trafalgar.

Inventing Decisive Naval Battle

The emergence of the capital ship in early modern Europe — especially the great three-decker ship of the line — created an instrument that could be collectively conceptualized as a distilled representation of the nation’s power, and then dramatically delivered on demand in the pursuit of national power and glory. Moreover, the biggest battleships were made to be painted en passant, as the living procession of power.

Grand, maritime canvases were the CGI cinema of the eighteenth century. The great ship’s onrush, in fiery pigment, released a sensation of power no longer dependent on battle. Rather, battle was now the dramatic stage for the great ship portrait, framing its impetus.

After 1789 all that changed. The capital ship became, for a brief era of revolutionary war (1794-1805), more like wrathful Achilles: The cutting tool of full ceremonial battle on behalf of the nation. Trafalgar, in its tightly choreographed stagecraft and its cathartic payoff, surely deserves the title of “peak ceremonial battle.” It was the battle that made modern Britain.

Trafalgar was the creation of Horatio Nelson — and his immaculate child could not have come at a more propitious — or necessary — moment in British national life.

Napoleon had already roughed out the paradigm of land battle in Europe — a ritual ideal of peak victory that would curse Modernity through 1945. Nelson absorbed for England at sea the revolutionary zeitgeist Bonaparte realized on land.

Simply, Nelson appropriated Napoleon’s battle system 5 and re-mastered it for fighting ships. Just as Bonaparte overturned war on land — all at once — at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels, so too did Nelson. Just as Napoleon, on the field, had to overcome eighteenth-century dogmas of engagement, so Nelson had to find a way to successfully abandon a similar dogma in sea fights.

The eighteenth-century solution for battle was to privilege formation over fire and shock in the pursuit of tactical control. Napoleon re-imagined combat formation so as to quickly intensify both fire and shock, and also bring rapid closure in engagement.

Naval combat in the eighteenth century was even more rigidly monitored. The line-of-battle insured the integrity and survival of one’s own fleet — and that of the enemy as well! Hence battle inherently inclined to the ceremonial, like a ballet.

Thus, Nelson’s complete lack of tactical inhibition at St. Vincent, the Nile, and Copenhagen echoes Napoleon’s heroic, world-shaking generalship at Rivoli or Marengo. There is even a closer resonance in terms of shared acts of sacrifice: Nelson’s unforgettable, cinematic, double-seizure of San Nicolás de Bari and San José was prefigured by Napoleon’s seizing the battle standard and rallying his troops at the bridge of Arcole, three months earlier. Both Napoleon and Nelson knew that sincere, sacrificial demonstration was essential to bind identity in this new era of religious nationalism. Only Nelson made such sacrifice intrinsic to his life achievement.

Nelson’s life was the acme of iconic leadership. Yet how could even the most charismatic and creative man make a single battle the transcendental metaphor of modern British identity?

Nelson crafted a plan to fulfill both practical and ceremonial goals. Only his command of both could achieve this end. Trafalgar’s ritual script, below, was actually built on, and then transcended seventeenth and eighteenth-century battle art. It was extensible enough to easily embrace the iconography of Jutland.

Before the Battle:

The Gathering

The Grand Chase

The Night Before Battle

The Heroic Adjuration

The Battle:

The Grave Procession to Battle

The Rupture as Decisive Act

Peak Struggle of the Melee

The Sacrifice

After the Battle:

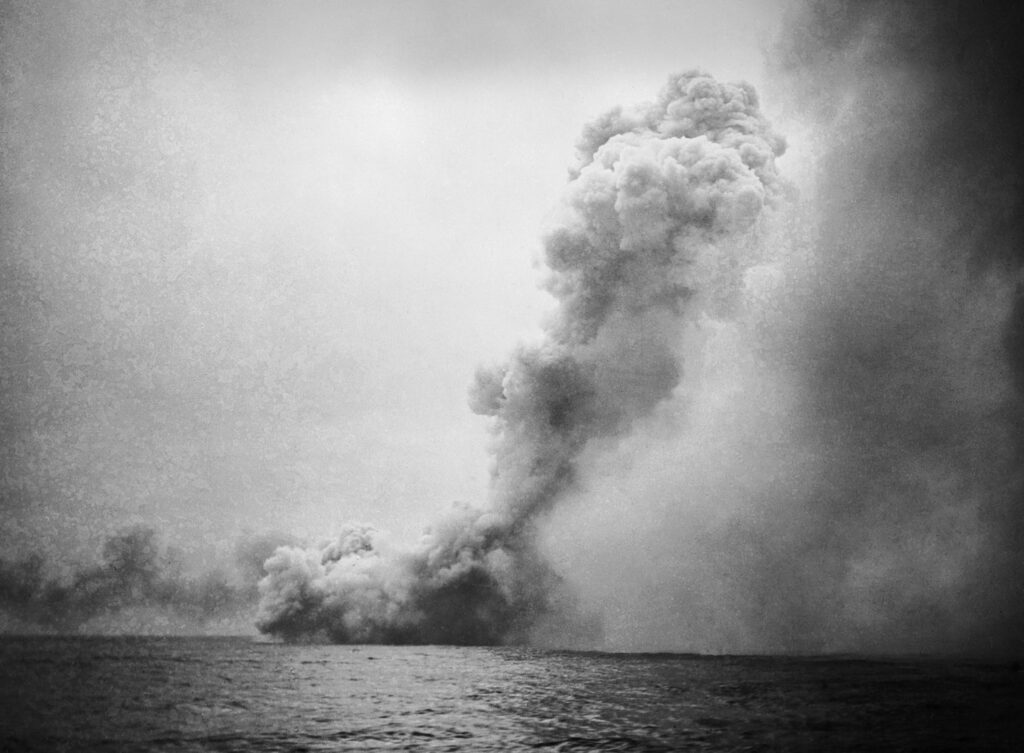

The Storm — The Cleansing

Lamentation on the Road Home

Homecoming and Glorious Funeral

Apotheosis and Memoria

People and elites arguably were already prepped emotionally — by Cape St. Vincent, the Nile, and Copenhagen — for his transcendental gift of Trafalgar — a metamorphosis of national identity consummated just ten years later, at Waterloo.

21 October was Britain’s national investiture. Going further, Nelson’s grand funeral bound the nation to the martyr’s sacrifice. The funerary rites were like a Roman imperial triumph, a coronation, and an apotheosis combined. A new nation was celebrating itself, drawing strength from Nelson’s sacrifice, cementing a Britannic vision of “eternal victory.” 6

How Ceremonial Battle Took Control (1805-1914)

Trafalgar pulses with the raw power ceremonial battle can deliver — where raw power is the substance of historical memory. A great battle is never just a fighting event, and battle does not end with the coming of night. It lives on, to be reenacted forever in the collective mind of the nation. Reliving the battle itself becomes the rite itself. Thus, ceremonial battle is scripted in the actual performance — then to be re-enacted through ceremonial devotion, where with each reiteration it again becomes alive.

Think of Trafalgar as the liturgy of the British nation, for was not Nelson the father, and the Royal Navy the midwife in the birth of the British nation? Consider:

- Was not the United Kingdom, truly cemented after 1797, now Navy-made?

- Was not the Navy – and the nation – now the uncontested “monarch of the seas”?

Nelson wrung from the world, for Britain, an entitlement ratified by natural law. Now its navy was immune, practically even inoculated, from straight-up battle challenge at sea. In practical terms, to maintain its exalted stature and station, all the navy needed was an occasional, ritual combat demonstration. For example, a) small ship, mostly gunboat engagements, b) stately, ceremonial bombardment of coastal forts, or c) the rare, actual sea fight against a parvenu (“oriental” foe like Muhammad Ali at Navarino Bay).

Free at last of existential threat, the Royal Navy relaxed itself into a military lifestyle enterprise. It was no longer bound by existential threat to seek extraordinary talent through social mobility. Gentleman mores — and Gentlemen rules — were now back in force.

“She blinded me with Science!” 7 Andrew Gordon argues 8 that the Victorian ethos gave its full faith to the power of science, and the promise of ships and squadrons precisely controlled. Battle mastery was guaranteed by the march of science. Rules of the Game highlights the triumph of Victorian rules over unruly reality. Yet a return to order-of-battle, as unbending as the eighteenth century, was never recognized as spiritually contravening Nelson.

The mythic narrative forged by Nelson became so embellished it became a kind of scriptural narcissism. Victory was thus foretold, and fully merited. Early Victorian historians gave this entitled feeling full literary ratification, in Napier’s extravagantly fulsome chronicle of the Peninsular War 9 — then to be codified forever in Edward Creasy’s Fifteen Decisive Battles of World History. 10

Mahan took the spirit of the late Victorian age to its logical end — by making decisive battle a Social Darwinian test of national worthiness to exist. If Nelson transformed battle into a ceremony of national apotheosis, Mahan appropriated Nelson’s template and made it a make-or-break moment. In Mahan’s grand clash of battle fleets, the nation either rose to meet its destiny, or was cast into historical despair. Mahan, divinity-schooled, brought the apocalyptic Prussian vision of Vernichtungsschlacht to war at sea.

Mahan had burdened every great power navy with an unobtainable prize. Like the Golden Fleece, guarded by the British Colchian Dragon, true sea power was always just out-of-reach. 11 Imperial Germany sought to claim the mantle, exclaiming that they would take it by main force (from Britain by right of decisive battle: Der Tag), or die trying. No one took Tirpitz’ “risk fleet” pretension seriously: Its boilerplate rhetoric only reinforced Mahanian zeitgeist: That all roads lead to decisive fleet battle. When deterrence fails, decisive battle rules.

Tsushima pushed decisive battle mania into overdrive. Togo was the new Nelson. Worse for Britain, the perfect battle of its time had been pulled off with ironclads actually built in Britain. Tsushima may have nodded to Nelson, 12 yet Togo had historically upstaged Britain, and the ceremonial grass crown was now Japan’s.

To sum up: 1) British identity was inseparable from naval supremacy, 2) The navy was unchallenged for a century, 3) It had become an upper class lifestyle club, 4) Its technology worship made it feel on top and untouchable, 5) National literary authority bolstered this natural superiority, 6) Yet the American, Mahan, had created a new and existential bar that the navy must meet and pass in its next test, 7) Aspiring great powers, especially Germany, Japan, and the United States, were all too eager to unseat the old lion.

Great Britain and her Royal Navy went to war in 1914 burdened by Trafalgar’s insurmountable bar, yet also by a public expectation 13 that it must whip the Kaiserliche Marine and put pay to German arrogance. Yet there was also the urge to show the world that the Grand Fleet could still teach arriviste allies and insouciant rivals — that Britain would stay on top, all trends notwithstanding.

How Admiralty Subordinated Strategy to Ceremony (1805-1914)

One-hundred-twelve years after Trafalgar, the Royal Navy was deeply invested in a strategic dilemma of its own making. Moreover, this was a grand Catch-22, driven by the naval programs of all the great powers. Yet this dilemma was also a paradox:

- Decisive (ceremonial) battle was believed to be the natural outcome of great wars at sea, and represented the culminating point of all naval strategy.

- Yet, as capital ships became ever more powerful and precious, and fewer in number, it was essential not to risk them until the moment of decision. So who would know for sure when the moment of decisive risk arrived?

Historical experience supported the judgment of paradox. A century of victory at sea, was not, in fact, secured by fleet action. Battle fleet blowouts, like Lissa and Tsushima, had little impact on wars’ outcome.

In contrast, victories that altered the course of war were almost all combined operations, with naval fire support and amphibious assault. Hence, the Royal Navy was a force of decision in a series of bombardments: St. Jean d’Acre, Taku, Pei-ho, Bomarsund, Kinburn, Shimonoseki, and Alexandria; just as were Federal squadrons at Mobile Bay and Fort Fisher. 14 “Ships only” fire assaults, like those at Algiers and Sebastopol, were in contrast inconclusive.

The ship tools of real decision were in combined operations, transporting armies, and guarding shipping. Yet national passion — and treasure — were invested in a grand fleet for a battle that would not be fought. Hence, when war came, the ships actually needed were often not there. They had to be cobbled together, desperately, in a rush. 15

Worse, a score of successful campaigns was presented to the public as show ship triumphs: Great battleships with “hearts of oak” lineage hearkening to the sea fights of centuries past.

Hence, in contemporary media presentations of combat at sea, battleships were always front and center: Implacable at Algiers, Asia at Navarino Bay, the screw battleships at Sebastopol, the regal white Alexandra and grim Inflexible at Alexandria. Indeed, comparing the ironclad line-up in battle action with ironclads in elegantly studied repose — say, the Mediterranean Fleet in Malta vs. that same fleet bombing Arabi Pasha’s forts — the emotional and aesthetic delivery is the same. 16

This was the dilemma: The capital ship in ceremonial mode had become coterminous with a world consciousness that had yielded to and embraced British naval authority. To a very great extent, capital ship ceremonial was Britain’s ticket to success, and thus big ships ritually employed gradually came to substitute for an actual fighting fleet that had not seen real action since 1814.

Yet this strategic formula rapidly eroded after 1900. New great powers — Germany, the United States, and Russia — were suddenly competing hard against a ceremonial British naval supremacy. 17 Britain vowed to keep up, and so it did. Yet it soon found it simply could not build quite enough capital ships. 18

In the 1850s, at the climax of the wooden steam navy, a 101-gun battleship cost .00013% of Britain’s GDP. 19 The big new ironclads, in contrast, cost .00050% in the 1870s. The new, standard battleship of the 1890s cost .00069%, while the big armored cruisers cost even more, at .00072% — plus so many more of them were needed. To preserve its precious ceremonial position, against rising powers with equal or greater economic output, Britain faced future bankruptcy.

Jackie Fisher stole a march on competing navies with Dreadnought, which for a moment allowed the Royal Navy to build a single, “all big gun” battleship that might lessen the strain on naval estimates. Yet as other powers, including France and Italy, and even South American navies, started clamoring for dreadnoughts, the race drove costs ever higher. By 1912, with Queen Elizabeth, each new “super dreadnought” claimed .00125% of UK GDP.

Dreadnought mania — 1907-1914 — distorted, and then tore apart, Britain’s comfortable lock on strategy-by-ceremony. The Admiralty response was reflexive: To build, build, build. 20 But all those dreadnoughts meant, equally, a relative dearth of all those other ships that let navies actually make war.

Battle Failure Saved by Storytelling

Britain and her navy went to war with a fleet steeped in sacred battle ceremonial. Yet the Admiralty announced that it would conduct a “distant blockade” of Germany, in contrast to Nelson’s intense, in-your-face sea investment of Brest from 1803-1805 — that guaranteed victory at Trafalgar. “Passive” may have been prudent, yet it was also the antithesis of Nelson. Still, the British public bought it: “We can’t risk the battle force, until the Grand Fleet is perfectly positioned to annihilate the Hun.”

After the war, Churchill gave us the famous final spin on Jutland, that the Grand Fleet Commander, John Jellicoe, was “the only man on either side who could lose the war in an afternoon.”

This studied quip is the summation of Britain’s entire after-action historical self-exculpation. In 1914, “England expects” the dream: For Jellicoe to fulfill the geas of Nelson. Before, he was the only man who could win the war in an afternoon — and its grass crown of destiny. After, somehow, Britain’s destiny is instead fulfilled by not losing.

If Trafalgar is your yardstick of victory, then “Not Trafalgar” simply won’t do. If, in contrast, the Grand Fleet achieves its decisive strategic effect simply preserving itself, then why risk battle at all? Here Churchill reveals the true wages of ceremonial battle. By promising a kind of national transcendence, then not delivering, stumbling badly in the event, and then saying, in lofty retrospect, that doing nothing was the plan all along — and by the way, “nothing” succeeded magnificently — is to risk Britain’s public confidence, and the world’s respect. 21

“After Jutland” — meaning, how the story would be retold in history — became a far tougher battle than the dreadnought clash itself. Although this after-battle narrative was finally won, it was a literary-strategic victory with dire consequences of its own.

Three “After Jutland” explanations were required. 22 The first assured that the technical things that went wrong would be fixed, first thing. Andrew Gordon more than adequately addresses the Royal Navy’s response — which was almost wholly successful. 23

The second argued — through leaks, gossip, and innuendo — that Jutland’s outcome was a failure of command leadership. Jutland was no extravagant defeat demanding newsreel beheadings. Under rather less pressure, British leadership simply needed to suggest that poor judgment, perhaps, let things slip away. Navy and Nation were off the hook.

The Third explanation was a real challenge. Jutland betrayed prewar expectation. Hence, post-Jutland argued the obvious: That war is behind us. We need to be ready for decisive contests to come. Jutland helped make a better fleet, so that next time we will surely prevail. 24

Post-Jutland narrative was about massaging the neuralgia of regret. British propaganda triumphed over Germany. In Culture of Defeat, Wolfgang Schivelbusch dissects how German Informationsspezialisten was out-foxed by British narrative. 25 Why not Britons too?

Yet there was also a fourth problem: How to turn strategic passivity into a virtue.

What the Allied coalition needed most in World War I was to work together. Urgently, this meant getting war goods to a Russian empire critically short of guns and ammo. Yet Germany had closed both the Baltic and Black Seas.

The great captains of the heroic age (1793-1815) were always more aggressive. This is exactly what the Admiralty ordered after Trafalgar. Saumarez in the Baltic forcefully supported the British money that drove the last, victorious coalitions against Bonaparte. 26

Even in Victorian times, battleships were used to strategic effect. Napier and Lyons in the Baltic were able to bring a distant war in Crimea right to the Czar’s doorstep in St. Petersburg. 27 These were real strategic effects, wrought by — or at least enabled by — capital ships.

In 1878, Geoffrey Thomas Phipps Hornby aced the ultimate G.A. Henty boy’s exploit. 28 He forced his single-screw ironclads through the Dardanelles in the teeth of a blinding snowstorm on St. Valentine’s Day to anchor in the Golden Horn, halting the Russian onslaught in its tracks, saving the Ottoman state.

Thus, 1914 was a golden opportunity for Britain’s capital ships. Why not again? Why not assemble the enormous host of armored ships acquired in the frenzy of ceremonial competition, and use them to make something “decisive” happen?

Yet the capital ships that delivered real, strategic agency were German. The daring flight of the Goeben to Constantinople brought the Ottoman Porte over to the Central Powers. Then, Operation Albion (1917) was the only time a capital ship fleet had real, strategic effect.

Ironically, Operation Albion mirrors of British Baltic operations during the Crimean War. In August 1854, the allies took the fort at Bomasund, in the Åland Islands. By the end of 1855, the Franco-British fleet was ready to bombard and besiege the main fortress of Kronstadt, directly threatening St. Petersburg. 29 Russia was leveraged out of the war — with new ironclads as the fulcrum. In September 1917, Germany assaulted the West Estonian Archipelago, opening the way for a move on Petrograd: Still the imperial capital. This time, German dreadnoughts were the fulcrum of victory.

Britain tried this exactly once. It took the form of a battleship coup de main. On 18 March 1915 De Robuck’s fleet tried to force the Hellespont narrows “by ships alone.” 30 Perhaps de Roebuck was channeling Phipps Hornby. Britain’s forlorn attempt to force the Straits ended in shameful disaster.

More shameful still was its feckless indiscipline, its inattention to specialized auxiliary support, and its dismissal of combined arms. 31 If a strategic coup was beyond Royal Navy ability in 1915, it was certainly not beyond its means.

Yet failure at the Dardanelles was so breathtaking that it made capital ship caution — for the rest of the war — seem prudential. It would be folly to assault the Central Powers’ hold on the inner seas. Risk had triumphed, and Grand Fleet passivity was the only reasonable option.

Yet Britain found a way to turn strategic passivity into strategic virtue through simple logic: Because the Grand Fleet was existentially irreplaceable, preserving its existence was the prime directive. Hence, reducing risk was the only path to victory. Never mind that an undisturbed German battle squadron set up Russian capitulation in 1917. That was out of sight, out of mind. It is easy to discard “a quarrel in a far away country between people of whom we know nothing,” into a “forgotten war.” 32

The Wages of Ceremonial Battle: “A New Beginning” 33

By airbrushing out strategic naval alternatives, British narrative spinmeisters had rescued ceremonial battle. Washington Treaties made the serendipity complete, when world powers ratified capital ship status. International treaty declared dreadnought ownership alone to be the supreme yardstick of national power.

The real naval war of 1914-18 was decided, rather, in 10,000 battles: To-the-death fights between unkempt little ships like trawlers, sloops, gunboats, torpedo boats — and U-boats. The decisive weapons were torpedoes and mines and “depth bombs.”

Yet after the war, navies discarded their thousands of decisive little ships. During the next twenty years, the Royal Navy built a single minelayer. Admiralty ordered not a single naval exercise on the defense of a slow merchant convoy. 34 Asdic, the new wonder weapon, suddenly made the submarine yesterday’s threat. 35

Ironically, the Washington treaties streamlined command and control by severely reducing battle fleet numbers. Smaller squadrons meant smarter maneuvering during battle. Plus, computerized fire control and air spotting meant American battlewagons were consistently hitting out to 26,000 yards. 36 The battle line was reborn.

Fire control confidence renewed decisive battle. Jutland narrative spin now worked to perfection. “Unmanageable armadas meeting in North Sea mists on a dying afternoon could never be a recipe for decision,” postwar naval opinion seemed to say. American and Japanese mind’s eyes were in full agreement. What North Sea Britain could not achieve, America and Japan would surely, on the Pacific stage, fulfill.

Trafalgar still stalks the 1920s and 1930s. Every war game and every fleet exercise still hammered: Decisive battle. Hence, Britain’s propaganda “save” was slowly lost.

What mollified British elites, former allies found cringe-worthy.

Commander Holloway Frost offered this damning epithet in his take on Jutland:

Personally, we believe that the whole attitude of the British Navy had changed since the days of Drake, Hawke, Jervis, Nelson, and Cornwallis. Then it was young; now it had grown old. In the old days, England was a small country fighting for its place in the sun. Its statesmen, soldiers, and sailors were willing to take their chances. When they won, they doubled the stakes and gambled again. Now, the British Empire covered the globe. Its task was not to get more, but to hold what it had. Its national policy was defensive, rather than offensive. That affected its naval strategy and tactics and turned the British Navy to thoughts of defense, rather than offense. 37

The tiled floor of Pringle Hall was the giant maneuver board for naval war games. 38 There are 318 game histories — from 1919-1941 — in the Naval War College archives. One-hundred-six were purely tactical, and seventy-one of these were battle line board maneuvers. Fifty-two battle games were against the RED battle fleet, of which forty-eight called for decisive action, in which the battle “plan approximates the general plan and ideas followed by both fleets at Jutland.” 39

Yet the U.S. Navy was not even refighting forty-eight new and improved Jutlands. Instead, American officers sought their own Trafalgar: Their own, awaited destiny. These games were a kind of naval yearning made flesh. From a 1941 bestseller:

The American Fleet would cross the Pacific at about the speed of translation of a cyclone — between 10 and 15 knots. It would resemble a cyclone in a more significant phase, leveling everything in its path except a stronger fleet — and a stronger fleet does not at present exist. 40

Gorgeous battle force geometry, with its starburst patterns of supportive ships, came to permeate the calculations of battle itself. Fire control’s ritual precision, combined with ship choreography, like a grand ballet, became battle’s pristine vision: So precise that the decisive gunfire phase in the clash of battle lines might last for as little as twenty-seven to eighty-four minutes. 41

And battle victory was America’s by reason of its spiritual superiority. This was explicitly commanded in Naval War College fighting instructions:

- The moral factor in battle is predominant. 42

- Such must be the will to win that nothing short of complete victory will be accepted. 43

- The moral factor to our benefit lay within the spiritual reaction with the enemy. 44

Here, the Nihon Kaigun was the U.S. Navy’s mirror, where an American grand fleet would meet an equally disadvantaged Japanese Höchseeflotte. Had not the Washington Treaties equally stacked the cards against Japan?

For Japan, German performance had a silver lining. Germany’s 60% fleet held off the British to advantage: Hence Japan concluded that Germany won the Battle of Jutland against heavy odds. Moreover, “if Britain could not defeat an inferior fleet 500 miles away, how then could she beat one that lay 10,000 miles [away]?” 45 Furthermore, the imperial fleet concluded that even a 10% increment — along with an edge in technology superiority not unlike that enjoyed by the Höchseeflotte — could cinch victory against either the two top fleets. 46

Yet Japan, by 1936, was well on that way to qualitative equality with the U.S. Navy. 47 Moreover, this baroque, decisive battle-to-be keyed decisively off German performance at Jutland. Japan had no doubt that Mahan’s sea power baton had now passed to them.

Japanese-American ceremonial battle became their mutual persona: 1) Both sides agreed on the need for a decisive contest, 2) The moment of decision occurs in a full, clear, and brilliant Pacific light, with a calm sea stage setting, 3) May the better man win.

An absurd premise, yet interwar literature fed easily on its assumptions. Hector Bywater’s 1927 bestseller, The Great Pacific War, set the tone. 48 Tōta Ishimaru’s Japan Must Fight Britain — published in 1935, when war was already a cloud bigger than a man’s hand 49 — was a savage portrait of a Royal Navy fall just like Russia’s at Tsushima; while Puleston’s identical battle fleet showdown in Navies of the Pacific was a sure U.S. win.

And what, at last were its remains of the day? Jutland was a cautionary tale. Yes, said the U.S. and Japan, to ceremonial decisive battle is still the way to go. As Britain failed, the Grail is now ours to seize. Paradoxically, post-Jutland spinmeisters salvaged victory from defeat after all — just not for Britain. It had become the strategic motivation of its biggest naval rivals.

British fire breathers might still rail to empty effect:

Because our Fleet, inspired by a great tradition and a great man, recognized that to win you must attack — go for, fall upon, fly at the throat of, hammer, pulverize, annihilate — your enemy. 50

Yet there was a bitter taste: The record of battles fought in the line is one long, practically unbroken story of indecisive results. 51

The evidence seemed inescapable: A no risk navy had lost its Nelson touch. In Jellicoe’s words:

… although the total destruction of the High Sea Fleet gives a greater sense of security, it is not wise to risk the heavy ships of the Grand Fleet in an attempt to hasten the end of the High Sea Fleet. … I do not think such risks should be run, seeing that any real disaster to our heavy ships lay the country open to invasion. 52

Or, as Herbert Richmond lamented, three months before Jutland:

The Navy has completely lost the spirit of the offensive: I cannot find a trace of it in any flag officer except Bacon. We shall have a shock one of these days, I am certain. 53

Cdr. H.R. Stark (future CNO) was less kind: The Grand Fleet at Jutland “lacked the fighting edge, the offensive spirit, the will to win.” 54

Another harsh consignment:

Looking back over the intervening twenty-three years, it is difficult to avoid, it is difficult to avoid the impression that Jellicoe’s tactics at Jutland, whether wise or unwise, constituted the first step-down from worldwide maritime supremacy. 55

Such are the wages of ceremonial battle. Yet such payment is shot through with exquisite irony.

Yes: Britons and their Grand Fleet could not deliver a second sacred battle. And yes: It is also true that, in the future, it would be America and Japan that brought the trophy home. Yet ceremonial demands meant that repeats risked failure for them too. Japan had its second Tsushima at Pearl Harbor: A victory of staggering proportions. Yet false pride, perhaps, tempted them to snatch a sequel at Midway. Instead America, shamed and humbled six months before, found its own transcendence.

Pearl Harbor and Midway perfectly fit the temple template of ceremonial battle. Japan scripted both Pearl Harbor and Midway to be perfect engagements. Yet while Operation AI was executed without the Rengō Kantai, the imperial high command wanted the entire line-of-battle present at Midway. Hence, the demands of ceremony trumped victory.

Sacred ceremony cannot be denied.

Why Work So Hard for the Wages of Ceremonial Battle?

Why did ceremonial battle — decisive fleet action — become central to Modernity, while in centuries before such combat outcomes were greeted more as a rare bonus?

- The cult of the nation state was fueled by the prospect of national transcendence. The comet’s trail of decisive battle could fulfill this need, igniting a collective feeling of unity, shared sacrifice, and a mythology of unmatchable national performance.

- Napoleon’s electric campaigns, one neon moment after another, showed it could be done — and Trafalgar showed it could be done at sea.

- Moreover, this sea passage — Britons’ preferred battle medium — highlighted the exertion of great ships, which, themselves, personified British identity and divine assurance, as with Rome, of “eternal victory.”

- Victorian era ideologies marked chosen tribes as “born to rule,” for whom decisive battle was the sign of destiny. Alfred Thayer Mahan made this prophecy of Sea Power, with Trafalgar its lodestar — resurrected in 1905 at Tsushima.

- With the dreadnought battleship, the Word was made flesh. The capital ship transformed in fifty years from a sailing, wooden ark rooted in centuries’ past, into a gleaming, steel ark with brooding great guns: The most powerful engine yet devised by Man.

Modernity’s vectors pushed an irresistible convergence of need and desire for both navy and nation: A proud American dreadnought on the two-dollar bill, Höchseeflotte steaming on the fifty-mark note. High analysis in Scientific American focused on new U.S. battlecruisers. America’s most popular weekly, LIFE® magazine, lovingly showcased our battleships — in color. In Depression movie matinees, say, in Springfield Ohio, audiences would burst into cheers when newsreels showed our battle fleet in the gleaming Pacific sun. 56

Such vignettes show how ceremonial battle trumped overwhelming recent war experience. Thus the Royal Navy after World War I pushed mine and submarine warfare to the margins, and downplayed the potential of aircraft at sea.

Celebrating their ships and fleets has been the nation’s naval mission for centuries. 57 Hence the magic story of decisive battle perfectly tantalized society in an age of religious nationalism.

Yet Tsushima — the last such perfectly transcendent battle — was a shocking reminder that decisive battle was also all-or-nothing and existential. Great powers — with their dreadnoughts — desperately desired the fruits, and yet were spooked by the terrible risks of the very event they sought.

An unspoken solution emerged: Replace battle (risk and chaos) with ceremony (order and control). Continually re-evoke decisive battle through fleet ceremonial — without ever having to recreate it — like Britain for a century after Trafalgar.

Nelson offered a ready-made mythology. Naval exercises, fleet reviews, port visits, and state occasion — regular sorts of ship ceremony — could thus be built out to include relatively “safe” ceremonial combat like shore bombardments or engagements with lesser naval foes.

Trafalgar’s shelf life lasted a whole century: Authority that just kept giving and giving. Other nations had so much less to work with. The United States had Farragut, the Austrians, Tegetthoff. The Russians thought they had Makarov until he blew up in 1904. Japan of course found its Nelson at Tsushima.

It is worth underscoring that Japan had its second decisive ceremonial battle, and the U.S. its first within six months of each other: Pearl Harbor and Midway. As it unfolded, Pearl Harbor was perhaps the most perfect of ceremonial battles. In pushing for its third, at Midway, Japan met terrible defeat; a tragedy set up, in large part, by Nihon Kaigun‘s insistence on a massive, coterminous, and entirely unnecessary trans-Pacific choreography involving most of the Combined Fleet.

America, not Japan, seized the “miracle of Midway.” Seventy-seven years later, the U.S. Navy is still channeling Midway as its sacred decisive victory. Although PACFLT brought little or no ceremony to the actual battle, Midway has become a ceremonial industry to rival Trafalgar’s. Midway has an equally imperishable shelf life. Midway remains the moment of destiny — to be re-consecrated again and again, like a liturgy.

A decisive battle navy will always seek ceremonial battle rather than the unknowable of the next war. Ceremony is certain, and gives back what uncertainty takes away. Yet no naval person will ever associate “ceremonial” with “battle.”

What are they afraid of? Are they afraid that linking ceremony to battle will undermine the serious business of the navy, or make the navy seem like some night club act — as just some “smoke and mirror” entertainment?

The American ethos cannot see the bigger significance of ceremony, even as the nation indulges itself in sacred emotion: At an inauguration, a D-Day anniversary, the Fourth of July, or in commemorating 9-11. Navy ceremony — like the last hurrah of Enterprise, 58 or christening Gerald Ford 59 — marks outpouring emotions absent full self-awareness: Full recognition of what it means to be human. Ceremony, ultimately, is Mankind’s true assertion of collective authority and meaning.

Hence, an historic U.S. Navy investment in nuclear carriers — even at the expense of the fleet overall — is here to stay. For is not the “super carrier” still the embodiment of American identity? As Britons with Trafalgar, we will never weigh anchor on Midway.

Ceremony is not an accessory in navy ethos and navy life. Ceremony drives. Moreover, ceremony is intrinsic to battle. Trafalgar drove the passage to Jutland, as Tsushima to Pearl Harbor, and Pearl to Midway. We must better understand how this dynamic still shapes our passage to the navy’s battle future.

(Return to May 2021 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

- Linda Colley, Britons: Forging the Nation, 1707-1837 (Yale, 2009). ↩

- Yehudah Wallach, The Dogma of the Battle of Annihilation: The Theories of Clausewitz and Schlieffen and Their Impact on the German Conduct of Two World Wars (Praeger, 1986). ↩

- The evolution of the Roman triumph, and its centrality in Roman imperial life, is stunningly uncovered by Michael MacCormick, Eternal Victory: Triumphal rulership in Late Antiquity, Byzantium, and the Early Medieval West (Cambridge, 1991); and Sabine MacCormick, Art and Ceremony in Late Antiquity (University of California, 1981). Together, these two books show how necessary, even intrinsic, imperial ceremony was to the very substance of Roman authority, and how essential enactment of such ceremony was to ruling elite confidence and public trust. ↩

- A ceremonial impact explicitly celebrated in, the film treatment of a famous cycle of novels by Arturo Pérez-Reverte, and the second most expensive movie ever made in Spain. ↩

- Exhaustively (yet perfectly) laid out in David Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon (Scribner, 1973). ↩

- Roger Knight, The Pursuit of Victory: The Life and Achievement of Horatio Nelson (Roger Knight, Basic Books, 2005). ↩

- Thomas Dolby, Synth-pop, new wave single, 1982. ↩

- Andrew Gordon, The Rules of the Game: Jutland and British Naval Command (Penguin, 1997). ↩

- W.F.P. Napier, History of the War in the Peninsula and the South of France (John Murray, 1828), 40. ↩

- Edward Creasy, The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World: From Marathon to Waterloo (Hurst and Company, 1851). ↩

- The tragic irony in the short and overheated Anglo-German naval competition was the tone-deaf Tirpitz. He whipped up bristled Brits with his talk of Der Tag, so that the dominant navy actually came to believe, for a moment, that Germany sought to destroy them in a decisive (ceremonial) battle. We know of course that Tirpitz was exaggerating for effect — yet he exaggerated poorly. His intent was to deter British intervention in a future European war, but his true impact was to tell all Britons that the Höchseeflotte was gunning for their identity, and aiming to take it clean away in their own, German North Sea Trafalgar. Tirpitz’ disastrous policy mistake was to give every British apologist after Jutland the perfect, airtight argument that the battle was a slam-dunk victory. ↩

- Philip Towle and Nobuko Kasuge, Britain and Japan in the Twentieth Century (I.B.Taurus, 2007). ↩

- A geas can be compared with a curse or, paradoxically, a gift. If someone under a geas violates the associated taboo, the infractor will suffer dishonor or even death. On the other hand, the observing of one’s geas is believed to bring power. Often it is women who place geasa upon men. In some cases the woman turns out to be a goddess or other sovereignty. ↩

- To this list might be added, in terms of strategic effect, the anticipated British bombardment of Kronstadt by the five new Aetna ironclad batteries, which directly brought Russia to terms by 1856. ↩

- This was an existential issue for Britain in both world wars, where the sudden, urgent, desperate call for anti-submarine escorts took the form of requisitioning fishing trawler fleets en masse, and then pleading with warship yards to crank out purpose-built ASW escorts. This they did, several years late. In the fullness of war, Canada and Britain produced 445 Flower Class corvettes and River Class frigates — yet they had to be designed and built de novo in the midst of crisis, in pure reaction to the German onslaught, with every imaginable delay. ↩

- William Lionell Wyllie’s “Well Done Condor” might seem an exception from a persistent capital ship, front-and-center meme. His canvas celebrates the heroic action of a small ship, the gunboat Condor, yet the image defaults to a heavy visual background assertion, where the line of ironclads is clearly doing the heavy lifting in the sweltering, daylong bombardment. See it in the Royal Museums Greenwich collection, https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/12135.html ↩

- For example, the globe-griddling procession of Roosevelt’s “Great White Fleet,” or the grand opening, and subsequent “Kiel Canal Days.” ↩

- A dilemma exhaustively explored by Jon Tetsuro Sumida, In Defence of Naval Supremacy: Finance, Technology, and British Naval Policy, 1889-1914 (Naval Institute, 1989). ↩

- Data on British economic output is readily available, as well as ship construction costs. Calculating ship costs, as a percentage of GDP, is a better measure of both the true and “felt” cost of ever more expensive capital ships than, say, “constant dollars.” An alternative, percentage of parliamentary estimates, is more difficult to correlate, as ship expenditure is spread over several years. ↩

- A reflex perfected captured by Churchill’s quip on the public and parliamentary dreadnought panic of 1909: “The Admiralty had demanded six ships; the economists offered four; and we finally compromised on eight.” ↩

- Brave writers in the early 1920s reminded that a big victory might well have forestalled the German U-boat assault that almost brought Britain down in 1917. Plus, the overall Allied malaise at the end of 1916 would have been turned around by a real trophy win. Maybe winning “in an afternoon” was really important: Carlyon Bellairs, The Battle of Jutland: The Sowing and the Reaping (Holder and Stoughton, 1919), 265; C.C, Gill, What Happened At Jutland (Doran, 1921), 168: “And finally the unrestricted German submarine campaign would have been greatly hampered if not completely frustrated had the British fleet destroyed the German fleet at Jutland … On the whole, it should not appear an exaggeration to say that a second Trafalgar on the day of Jutland would have crushed Germany’s hope …” ↩

- In my 1973 Yale History Senior Essay — “The Fishing Off the Jutland Bank: The Search for a Symbol of Victory” — I suggested that the public, political response to Jutland might be divided into five successive phases (to 1973). This was a chronological treatment. I believe now that there was a more subterranean response-set that was never publicly acknowledged, and most likely never really consciously enjoined; yet vigorously pursued, notwithstanding. ↩

- Gordon, The Rules of the Game. ↩

- Even the dominant naval historian of the 1960s confidently affirms the effectiveness of post-Jutland reforms: Arthur J. Marder, From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow, Vol. iii, 212: “One can speculate that, had the Germans risked a pitched battle with the Grand Fleet six or eight months later, or, better, a year later, the outcome would never have been in doubt.” ↩

- Wolfgang, Schivelbusch, The Culture of Defeat: On National Trauma, Mourning, and Recovery (Picador, 2001), 218-225. ↩

- David John Raymond, The Navy in the Baltic, 1807-1812 (Ph.D. Dissertation, Florida State University, 2010); A.N. Ryan (ed.), The Saumarez Papers, 1808-1812, Naval Records Society, Vol. 110, 1968; Tim Voelcker, Admiral Saumarez Against Napoleon: The Baltic, 1807-1812 (Boydell, 2008). ↩

- D. Bonner-Smith, Russian War, Baltic and Black Sea, 1854, Official Correspondence, Naval Records Society, Vol. 83, 1943; D. Bonner-Smith, Russian War, Baltic: 1855, Naval Records Society, Vol. 84, 1944. ↩

- I am thinking here of the master, G.A. Henty, war correspondent, Victorian trendsetter, and hero to all Empire-minded boys, who published 122 historical novels, and was a nearly exact contemporary of Hornby. All his novels save one (about Nelson, of course) were Army focused, yet it is easy to imagine a yarn such as With Hornby Through the Dardanelles. ↩

- Basil Greenhill and Ann Giffard, The British Assault on Finland, 1854-1855: A Forgotten Naval War (Naval Institute Press, 1988); Michael Vlahos, “The British Assault on Finland” (review), Naval War College Review (45/1), Winter 1992. ↩

- Jeffrey Wallin, By Ships Alone (Carolina Academic Press), 1981. ↩

- Observations of a key participant convey the stratigraphy of hesitation and disorder, The Naval Memoirs of Admiral of the Fleet: The Narrow Seas to the Dardanelles (Thornton, Butterworth, 1934). ↩

- Neville Chamberlain of course was referring to Czechoslovakia, a country in the heart of Europe, while “Forgotten War” is the sub-title of The British Assault on Finland, 1854-1855 (see above). ↩

- Any good movie sequel properly alerts the audience; in this case, Friday the 13th Part V: A New Beginning (Paramount Films). ↩

- Stephen Roskill, Naval Policy Between the Wars: The Period of Anglo-Saxon Antagonism, 1919-1929 (Collins, 1968), 536. ↩

- George Franklin, Britain’s Antisubmarine Capability, 1919-1939 (Frank Cass, 2014). ↩

- Michael Vlahos, The BLUE Sword: The Naval War College and the American Mission, 1919-1941 (Government Printing Office, 1980). ↩

- Holloway Frost, The Battle of Jutland (U.S. Naval Institute, 1936), 516. ↩

- A contemporary image from the Naval War College Museum: LINK ↩

- Rear Admiral Harris Laning, President, Naval War College, The Naval Battle, May 1933 (Naval War College Naval Historical Collection), 3. ↩

- W.D. Puleston, The Navies of the Pacific (Yale, 1941), 242. ↩

- Capt. J.M. Reeves, “A Tactical Study Based on the Fundamental Principles of War of the Employment of the Present BLUE Fleet in Battle, Showing the Vital Modification Demanded by Tactics,” 20 March 1924, plates 4-7, Record Group II, Naval Historical Collection. ↩

- Department of Operations, “The Fire Action of the Battle Line,” 23 May 1932, p.2; “Cruisers and Destroyers in the General Action,” June 1936, p.1m, Record Group II, Naval Historical Collection. ↩

- Laning, The Naval Battle, 55. ↩

- Department of Operations, “The Fire Action of the Battle Line,” 45. ↩

- Michael Vlahos, “The Fishing Off the Jutland Bank: The Search for a Symbol of Victory,” (Yale History Department, Senior Essay (prize), 1973), 88. ↩

- James B. Crowley, Japan’s Quest for Autonomy (Princeton, 1966), 25. ↩

- Stephen Pelz, Race to Pearl Harbor: The Failure of the Second London Naval Conference and the Onset of World War II (Harvard, 1974). ↩

- Hector C. Bywater, The Great Pacific War: a history of the American-Japanese campaign of 1931-33 (Constable, 1925). ↩

- Tōta Ishimaru, Japan Must Fight Britain (Hurst and Blackett, 1936). ↩

- Arthur C. Marder, From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow, Vol. 1 (Oxford, 1967), 367. ↩

- H.W. Richmond, “The Service Mind,” Nineteenth Century and After, Jan., 1933. ↩

- A. Temple Patterson (ed.), The Jellicoe Papers, Vol. 1 (Navy Records Society, 1966), 232. ↩

- Arthur C. Marder, Portrait of an Admiral (Harvard, 1952), 201. ↩

- Commander H.R. Stark, Thesis on Policy, 32, Record Group XII, Naval Historical Collection. ↩

- Edwin A. Falk, “British Sea Power Since Jutland,” Yale Review, June 1939, 695. ↩

- In spite of the interwar tides of “isolationism” and “disarmament,” the Battle Fleet remained in the collective American imagination, the emotional symbol of security for this New World sanctuary. The writer’s father remembers audiences at movies cheering and throwing their hats into the air every time the U.S. Battle Fleet appeared at the end of the newsreel. This was the normal response to America’s strategic forces in the 1930s, Springfield, Ohio, the Heartland. As Adm. C.C. Bloch then CINCUS, wrote of a similar scene in California, 1939: “A friend of mine reports that his wife and child were in a movie house in Los Angeles, and had seen newsreels of a foreign navy in action, which left the audience wondering just how the United States Navy was. Immediately after the newsreel, your ‘Filming the Fleet’ came to the screen. During its showing and afterwards, the audience applauded with much gusto.” Adm. C.C. Bloch to Mr. Truman Talley, 7 November 1939, Bloch Papers, Naval Historical Collection, Library of Congress. ↩

- Henry Grace à Dieu, it is said, inaugurated the English tradition of “showing the flag” in 1514. ↩

- Retired from active service: LINK; Decommissioned: LINK ↩

- LINK ↩