Contents:

Introduction

The Booming Oyster Industry

Problems in the Emerging Oyster Industry

Regulation of the Oyster Industry and the Violence that Ensued

The Unsuccessful Oyster Police

The End of the Oyster Wars

The Tragedy of the Commons

Conclusion

Appendices

Zoe Friedman

National History Day

“And where there is boom, there is greed.” –John R. Wennersten 1

Introduction

The 1840s were a time of industrialization in the United States that transformed the scale and structure of American business, not just in manufacturing, but also in retail, transportation, service, banking, and financial industries. 2 Following economic panics in 1837 and 1839 that led to a national depression, there was an economic revival that started in the mid-1840s and continued well into the 1850s. 3 It was during this period, in the 1840s, that oysters became a well-known, popularized product in the emerging canned foods industry. Baltimore, Maryland was the center of this industry, having hundreds of canning houses operating by the mid-nineteenth century. Baltimore was the best place to have canning houses, the Chesapeake Bay was nearby and easy to access by water. Railroads were close and allowed for distribution to the rest of the country. 4 Two other east coast oyster beds in Long Island and Massachusetts could have been other centers for the oyster industry if they had not been previously dredged to depletion. 5

Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay was ideal for growing oysters because of its vast expanses,temperature and salinity. The Bay’s waters also had few predators for oysters, and were free of parasites that caused common oyster diseases. 6 Since there was no official regulation of the oyster industry , oystermen could harvest as many oysters as they wanted, making it a goldmine for industrious watermen. As with many successful businesses, competition arose. Maryland tried to bring an end to excessive competition in the Bay, as well as over-depletion of oysters, by passing laws that required a license to harvest oysters and prohibited certain harvesting practices. These actions unintentionally led to what is now known as the Oyster Wars. 7

The Oyster Wars were battles over oyster harvesting territory in the Chesapeake Bay that often became violent. 8 The peak of the Oyster War’s violence started in the mid nineteenth century and lasted until the late 1950s. 9 The start of the Oyster Wars was caused by illegal oyster poachers and legal oystermen that gathered in the Chesapeake. A lethal combination of greed and guns led to the Eastern Shore becoming a dangerous place to make a living. 10 Some oyster harvesters ended up dying in their endeavor to make money in the oyster trade. As a result, Maryland passed new laws to protect both oysters and harvesters. Despite many attempts at enforcement, these laws never fully worked. 11

The Oyster Wars provide a demonstration of why regulations sometimes fail to carry out the purpose for which they are intended, why they must be implemented carefully, and how regulatory compromises may cause conflict, even when they involve something as seemingly non-controversial as oysters.

The Booming Oyster Industry

Oysters were plentiful in the Chesapeake Bay in the early days of American colonization and there was no concern of shortages. As a Swiss visitor, Francis Louis Michel, wrote about the Chesapeake Bay in 1701, “The abundance of oysters is incredible. There are whole banks of them so that the ships must avoid them.” 12 Since oysters could not be stored for long periods of time, oystermen tended to harvest them in small batches in a shortened season, holding themselves accountable by following the “R” rule, which allowed for the harvest of oysters only in months that contained the letter “R.” 13

With the introduction of canning in the early 1800s, Maryland’s oyster businesses went through a rapid period of industrialization. 14 Canning, invented by the French in 1800, revolutionized the oyster industry. 15 Canning allowed oysters to last up to six months and be shipped worldwide, and when combined with clever marketing the oyster industry boomed. 16 Large, over-exaggerated advertisements pushing canned oysters were posted all over the country, increasing oyster demand. 16 Even the government hyped the oyster trade, with the Department of Commerce bragging in an advertisement in the 1800s that, “The Oyster Production of the United States is the Greatest in the World.” 18 The advertising worked. As one modern oysterman noted: “You could leave a coin on the street, and no one would pick it up. Leave an oyster, and it would be gone in a second!” 19

With oyster beds nearby in the Chesapeake, rapid population growth, and a well-developed rail system, Baltimore became the center of oyster canning in the country. By the mid-1800s, oysters were Baltimore’s second largest industry. 20 By 1894, Chesapeake Bay landings comprised around thirty-nine percent of the total U.S. oyster catch.

Problems in the Emerging Oyster Industry

Since there were initially no regulations limiting oyster harvesting, oystermen could take as many oysters as they wanted, and many made fortunes. In fact, in the 1800s oysters were known as “white gold.” 20 However, as more people flocked to the Chesapeake oyster industry, oyster stocks became depleted, creating competition over a limited resource.

Improved harvesting technologies made the oyster depletion problems worse. In the 1700s oysters were harvested using shaft tongs, a pair of iron rakes with handles joined together like forceps. During the 1800s a similar tool, called nippers, were commonly used. Oystermen who used tongs or nippers were referred to as “tongers,” and as more harvesters began utilizing these tools oyster harvests increased. These tools could only reach down to 32 feet at most in the water, and many harvested oysters would fall out of them. This made the tools environmentally sustainable, unlike what was later to come. 5 Dredges, 23 which oystermen also began using in the 1800s 24 had a metal frame, strong teeth, and a bag of heavy cord that allowed harvesters to scoop oysters in large quantities from the ocean floor. Oystermen used dredges to scoop up oysters by the bushel-full, often wiping out and destroying entire oyster beds.

The depletion of oysters caused bitter feuds over harvesting techniques and territory, and the Chesapeake Bay became a dangerous place as oystermen competed to harvest as many oysters as they could. Oyster hunters were willing to kill each other over limited territory, and tongers became angry as dredging for oysters increased, particularly in shallow waters where tongers worked. Dredges were first only used in deep waters that were previously inaccessible, but without regulations oystermen began using them in shallow waters, causing significant damage to oyster beds and ruining the livelihood of tongers. 25

Regulation of the Oyster Industry and the Violence that Ensued

In response to the damage caused by dredgers, in 1811 Virginia created a law to ban oyster dredging. Maryland followed suit, and in 1820 the first law was passed in Maryland pertaining to oyster harvesting, which outlawed all dredges in Maryland waters. 26 Maryland lawmakers said that they passed this law because dredges were digging too deeply into the ocean bed and scraping oyster beds down to the mud, permanently damaging oyster beds. 5 However, the more likely reason for the law was that the oyster tongers did not like the competition from the dredgers. 28

There had always been violent disputes among oystermen, but Maryland’s attempt to regulate the oyster industry added fuel to the fire. Historically, oyster battles were caused by disputes over the boundary line between Maryland and Virginia, and the new regulations did nothing to stop these tensions. 8 For example, in the winter of 1879-1880, around forty Maryland dredging boats entered the Rappahannock river in Virginia and began illegally dredging for oysters. The tongers in the area grew upset and tried to drive the dredgers away. In response, dredgers began shooting at tongers. The tongers complained to state officials, who agreed to provide the tongers with artillery, rifles, and ammunition to defend themselves. However, by the time these arrived, the dredgers had fled the area, already completing their work. 30

Maryland’s attempt to regulate oyster dredging exacerbated these territorial disputes and provided new reasons for conflict. Soon after anti-dredging laws were passed dredgers began to ignore them, making tongers angry and inciting additional violence. 31 In response, in 1854 Maryland began allowing dredging again for a fee, but only in Somerset County, Maryland, so that dredging would be focused in a single area. This unintentionally led to anger among harvesters outside of Somerset County, who were jealous of the legal use of more efficient dredgers by residents of Somerset.

In an attempt to level the playing field and stop ongoing disputes among harvesters, in 1865 Maryland passed the General License Act, which required all oystermen in the Maryland Chesapeake Bay area to have a paid license. These licenses were statewide, and applied to all oystermen no matter what tools they used to collect oysters. The General License Act also permitted dredging in certain waters of the Chesapeake, mainly those that were unreachable by tongs. The law was good for Maryland because it provided the government with much needed money. However, the General License Act was unpopular and ineffective, 32 as oystermen began ignoring it as soon as it was implemented. 33

Over the next several years, oystermen depleted deeper waters of oysters, and even worse began to dredge again in shallow waters. Maryland’s oyster laws had too many exceptions, and were not properly enforced. Violence continued, leading Maryland to take drastic action and create the Maryland State Fishery Force.

The Unsuccessful Oyster Police

The General License Law of 1865 was ignored because it lacked a method of enforcement. In 1868, Maryland established a State Fishery Force, known as the Oyster Police or Oyster Navy, to enforce the oyster laws. By 1894, the Oyster Navy comprised two steamboats, eleven sailing vessels, eight smaller “County” boats, and 120 men. This force was entrusted with enforcing the General License Law against illegal dredgers and those without licenses, and stopping general violence. 32 The Oyster Navy’s armed boats patrolled the Bay, enforcing the oyster laws with varying degrees of success. 35 The Navy fought a number of pitched battles with defiant dredgers, 36 and the sinking of dredger boats by cannon fire and the deaths of some scofflaws led to fewer violations of the law. 37

However, the Oyster Police forces were greatly outnumbered and had little power compared to the well-armed illegal oyster pirates. Their effort was dismal. They only managed to stop a small number of outlaws, and more violence came of it. 38 The Captain of the Oyster Navy, Hunter Davidson, described oyster harvesters as “so stimulated by the trade in the Chesapeake that Oystermen will risk any weather and are willing to kill to enable them to reach the handsome profits that are now being handed to them in the market.” 1 Even the tongers, who they were mandated to protect thought they were corrupt and ineffective. 5 In the end, the Oyster Navy could not compete with motivated oystermen, and was unsuccessful in preventing violence and the overharvesting of oysters in the Chesapeake Bay.

The End of the Oyster Wars

The end of the oyster wars is mainly attributed to a single act of violence, an incident involving an officer from the Oyster Police killing an illegal dredger from Virginia in 1959. 41 In response to the public outcry from this killing, in 1959 the Commissioner of the Potomac River Fisheries, H.C. Byrd, disbanded the Oyster Navy, as it was too controversial and clearly ineffective.

After that, Maryland used other methods to control the oyster industry, including various means of taxation, encouraging the private cultivation of oysters, and improving research into ways to protect oysters and oyster habitat. In 1975, Virginia and Maryland formed the Chesapeake Bay Legislative Advisory Commission to better manage the Bay. Presently, this Commission still takes actions to control the oyster industry in Maryland. Unfortunately, the overharvesting of oysters in the 1800s caused permanent damage to the Chesapeake Bay oyster fishery, which has never fully recovered. In 1880, the Maryland oyster industry was producing 71.9 million pounds of oysters per year; in comparison, by 1962, that number had dropped to 8.1 million pounds.

The Tragedy of the Commons

The over-industrialization of Maryland’s oyster industry provides an example of the “tragedy of the commons,” where individual users act in their own self-interest and hurt the common good by depleting a natural resource. 6 The failure of the Oyster Navy and regulatory efforts to address this problem serve as a cautionary tale for on-going conflicts over limited natural resources that exist today.

One example of this conflict is in the modern fishing industry in the United States and around the world. Much of the world relies on fishing for food and livelihoods, but without appropriate regulation, overfishing occurs, fisheries collapse and violence often ensues. 43 Currently, the United States is the “gold standard” around the world for effectively using fishing regulations to preserve natural resources. The agency that regulates fishing is NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 44

NOAA uses a creative fishing regulator scheme that allows regional councils made up of local fisherman and government regulators to determine how best to allocate resources. 45 Through these councils, fishermen feel like they have a voice in the process, preventing violent competition and ensuring that the industry (and fish) will exist for future generations. NOAA’s work shows how government agencies can work with industry to help resolve fights over natural resources.

Another present day example involves strip mining. In 1977, the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act was passed, which is the primary law regulating coal mining. This law minimizes adverse impacts on fish, wildlife and related environmental resources, and has stopped strip mining practices, preserving natural resources while still allowing mining activities. 46 Again, government has stepped in to regulate the mining industry’s impact on the environment, compromising with industry to allowed continued mining without a negative effect on the environment.

Conclusion

The Oyster Wars of the Chesapeake Bay were caused by competition for a limited resource, unsuccessful laws, and a lack of meaningful enforcement. During the wars, regulatory efforts were made to address the competition among oyster harvesters, along with their unpredictable actions and violence. These efforts had only limited success, and often caused the very violence they were meant to prevent. 47 The Oyster Wars show that just passing laws sometimes provokes conflict, and more creative solutions are often needed.

There are still large political debates over oysters in the Chesapeake Bay, and the oyster industry remains important to the Maryland economy. The Trump administration has proposed cuts in federal funding for Bay cleanup, which could negatively affect the oyster industry — however, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation hopes to add ten billion oysters to the Bay over the next seven years. 48 Fights over oysters in Chesapeake Bay and other natural resources are sure to continue as populations increase and resources dwindle.

We can learn the lessons for how to resolve these problems through the Oyster Wars, along with modern efforts to regulate natural resources that were created in response to them. Weak laws and poor enforcement will only increase violence and hurt the resource. Instead, government and industry must come together and make compromises or risk the destruction of a natural resource we hold dear.

Appendices

Appendix A

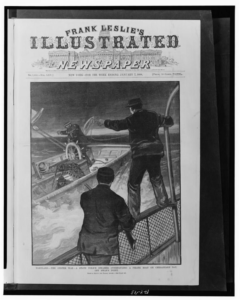

This newspaper image illustrates the violence between the oyster police and illegal oyster dredgers. It also shows the sinking of ships, and how exactly illegal dredgers were captured.

This newspaper image illustrates the violence between the oyster police and illegal oyster dredgers. It also shows the sinking of ships, and how exactly illegal dredgers were captured.

Image taken from: Maryland–The oyster war–A state police steamer overhauling a pirate boat on Chesapeake Bay, off Swan’s Point / from a sketch by Frank Adams. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/2001695520/.

Appendix B

This photograph shows oyster shuckers, as well as an inspector watching over them as they work. It shows how the oyster industry provided jobs, and was a part of Maryland history.

This photograph shows oyster shuckers, as well as an inspector watching over them as they work. It shows how the oyster industry provided jobs, and was a part of Maryland history.

Photograph taken from: United States Department of Agriculture, ca. 1914-1915, Arthur J. Olmstead Collection, PP133, MdHS. < http://www.mdhs.org/underbelly/2014/05/08/maryland-on-a-half-shell/ >.

Appendix C

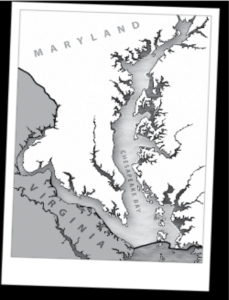

The dark areas of this map represent shallow waters in the Chesapeake, whereas the lighter areas represent deeper waters of the Chesapeake. It helps to illustrate where these waters were located, and where dredgers and tongers worked.

The dark areas of this map represent shallow waters in the Chesapeake, whereas the lighter areas represent deeper waters of the Chesapeake. It helps to illustrate where these waters were located, and where dredgers and tongers worked.

Map taken from: “Oyster Wars!!” Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, www.cbmm.org/pdf/ Oystering%20Curriculum6-10.pdf. Accessed 17 Feb. 2018.

Appendix D

This image shows one of the many advertisements for Baltimore oysters.

This image shows one of the many advertisements for Baltimore oysters.

Image taken from: Seaver, Barton. American Seafood: Heritage, Culture & Cookery From Sea to Shining Sea. Rev. and expanded 2nd ed., NY, Sterling Epicure, 2017.

Appendix E

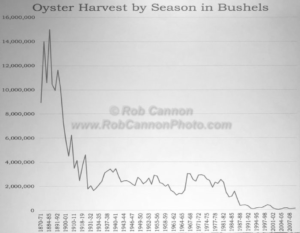

This graph displays the turning points in oyster harvesting as the years go on. When relating this graph to regulations on oystering at specific times, it can show its effect on the number of oysters harvested.

This graph displays the turning points in oyster harvesting as the years go on. When relating this graph to regulations on oystering at specific times, it can show its effect on the number of oysters harvested.

Graph taken from: — . Oyster Harvest by Year . Phototgraphy by Rob Cannon , www.robcannonphoto.com/photos/Cannon/Dorchester/images/page143.html. Accessed 17 Aug. 2018.

Appendix F

This image shows one of the cannons used by officers a part of the Oyster Navy.

This image shows one of the cannons used by officers a part of the Oyster Navy.

Photograph taken from: —. Oyster Navy Cannon . Photography by Rob Cannon , www.robcannonphoto.com/photos/Cannon/Dorchester/images/page151.html. Accessed 17 Aug. 2018.

Appendix G

This photograph shows a display of oysters from an oystering company. It shows the amount of oysters harvested, and how they were advertised.

This photograph shows a display of oysters from an oystering company. It shows the amount of oysters harvested, and how they were advertised.

Photograph taken from: —. Oyster House 01. Photography by Rob Cannon Photo , www.robcannonphoto.com/ photos/Cannon/Dorchester/images/page143.html. Accessed 18 Aug. 2018.

(Return to September 2018 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

- Wennersten, John R. The Oyster Wars of Chesapeake Bay. 2nd ed., Washington, DC, Eastern Branch Press, 2007. ↩

- Keleher, Tom. “The Debit Economy of 1830s New England.” Teach U.S. History.org, Old Sturbridge Inc., www.teachushistory.org.detocqueville-visit-united-states/articles/debit-economy-1830s-new-england. Accessed 17 Feb. 2018. ↩

- Hausman, William J. “Introduction, The Emergence of an Industrial Nation, 1840-1893. Immigrant Entrepreneurship German- American Business Biographies 1720 to the Present, German Historical Institute, www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/volume.php?rec=2. Accessed 17 Feb. 2018. ↩

- Seaver, Barton. American Seafood: Heritage, Culture & Cookery From Sea to Shining Sea. Rev. and expanded 2nd ed., NY, Sterling Epicure, 2017. ↩

- Cannon, Rob. E-mail interview with notes. 5 Aug. 2018. ↩

- Power, Garrett. “More About Oysters Than You Wanted to Know.” Maryland Law Review, vol. 30, no. 3, 1970. ↩

- Schulte, David M. “History of the Virginia Oyster Fishery, Chesapeake Bay, USA.” Marine Fisheries, Aquaculture and Living Resources, 9 May 2017, www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ fmars.2017.00127/full. ↩

- The Maryland and Virginia Boundary. (1874, Feb 26). The Sun (1837-1992). ↩

- “Commercial Fishers: Chesapeake Oysters.” On the Water, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, americanhistory.si.edu/onthewater/exhibition/3_5.html. Accessed 21 Feb. 2018. ↩

- Artillery against oystermen. (1883, Nov 26). The Sun (1837-1992) ↩

- Reported for the Baltimore, SunGeo Yellott. (1881, Dec 13). The Law of Habeas Corpus. The Sun (1837-1992). ↩

- Kennedy, Victor S., and Linda L. Breisch. “Sixteen Decades of Political Management of the Oyster Fishery in Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay.” Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 164, 1938. ↩

- Chowning, Larry S. Harvesting the Chesapeake Tools & Traditions. Rev. and Expanded 2nd ed., Atglen, PA, Schiffer Publishing, 2014. ↩

- Walsh, Richard, and William Lloyd Fox, editors. Maryland: A History, 1632 -1974. Baltimore, MD, Press of Scheidereith & Sons. ↩

- “Commercial Fishers: Chesapeake Oysters.” On the Water, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, americanhistory.si.edu/onthewater/exhibition/ 3_5.html. Accessed 21 Feb. 2018. ↩

- “Oyster Wars!!” Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, www.cbmm.org/pdf/ Oystering%20Curriculum6-10.pdf. Accessed 17 Feb. 2018. ↩

- “Oyster Wars!!” Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, www.cbmm.org/pdf/ Oystering%20Curriculum6-10.pdf. Accessed 17 Feb. 2018. ↩

- Seaver, Barton. American Seafood: Heritage, Culture & Cookery From Sea to Shining Sea. Rev. and expanded 2nd ed., NY, Sterling Epicure, 2017. ↩

- Oyster harvester from Farmer’s Market. Interview by Zoe Friedman. 9 Dec. 2017. ↩

- Livie, Kate. Chesapeake Oysters The Bay’s Foundation and Future. Charleston, SC, American Palate, 2015. ↩

- Livie, Kate. Chesapeake Oysters The Bay’s Foundation and Future. Charleston, SC, American Palate, 2015. ↩

- Cannon, Rob. E-mail interview with notes. 5 Aug. 2018. ↩

- History on the Chesapeake.” Waterblog, National Aquarium, 27 July 2016, aqua.org/blog/2016/July/History-on-the-Chesapeake. ↩

- “Oyster Wars Oystering Methods.” The Mariner’s Museum, The Mariner’s Museum, 2002, www.marinersmuseum.org/sites/micro/cbhf/oyster/mod007.html. ↩

- Correspondence of the, B. S. (1880, Jan 26). Maryland State Affairs. The Sun (1837-1992). ↩

- Miller, Henry M., Dr. “The Oyster in Chesapeake History.” St. Mary’s Museum of History and Archaeology, www.hsmcdigshistory.org/pdf/Oyster.pdf. ↩

- Cannon, Rob. E-mail interview with notes. 5 Aug. 2018. ↩

- Kennedy, Victor S., and Linda L. Breisch. “Sixteen Decades of Political Management of the Oyster Fishery in Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay.” Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 164, 1983; Correspondence of the, B. S. (1880, Jan 26). Maryland State Affairs. The Sun (1837-1992). ↩

- The Maryland and Virginia Boundary. (1874, Feb 26). The Sun (1837-1992). ↩

- “Oyster Wars Oystering Methods.” The Mariner’s Museum, The Mariner’s Museum, 2002, www.marinersmuseum.org/sites/micro/cbhf/oyster/mod007.html. ↩

- The Oyster War. (1851, May 20), The Sun (1837-1992). ↩

- The Oyster Trade—The Outlook—The Supply, &c., &c.” The Evening Capital, 24 July 1884. ↩

- “The Maryland Oyster Law.” The Evening Capital, 16 August 1884. ↩

- The Oyster Trade—The Outlook—The Supply, &c., &c.” The Evening Capital, 24 July 1884. ↩

- Capture of Oyster Boats. (1852, Mar 23). The Sun (1837-1992); Special Dispatch to the, Baltimore Sun. (1882, Feb 20). The Virginia Oyster War. The Sun (1837-1992); Correspondence of the, B. S. (1850, Sep 14). By Last Night’s Philadelphia Boat. The Sun (1837-1992). ↩

- Artillery against oystermen. (1883, Nov 26). The Sun (1837-1992). ↩

- More Oystermen Captured. (1850, Mar 15). The Sun (1837-1992). ↩

- Meyer, Eugene L. Chesapeake Country. 2nd, rev. ed., NY, Abbeville Press Publishers, 2015. ↩

- Wennersten, John R. The Oyster Wars of Chesapeake Bay. 2nd ed., Washington, DC, Eastern Branch Press, 2007. ↩

- Cannon, Rob. E-mail interview with notes. 5 Aug. 2018. ↩

- “Oyster Wars 1632- 1962.” Dymer Creek Environmental Preservation Association, 31 July 2014. ↩

- Power, Garrett. “More About Oysters Than You Wanted to Know.” Maryland Law Review, vol. 30, no. 3, 1970. ↩

- Glaser, Sara. “Fish Wars: How Fishing Can Start and Stop Conflict.” Secure Fisheries, 14 Mar. 2017, securefisheries.org/blog/fish-wars-how-fishing-can-start-and-stop-conflict. ↩

- “Laws.” NOAA Fisheries, 19 June 2017, www.fisheries.noaa.gov/insight/laws. ↩

- Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, 16 U.S.C. Chapter 38, Section 1801. ↩

- “Digest of Federal Laws of Interest to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.” FWS CLA, https://www.fws.gov/laws/lawsdigest/surfmin.html. Accessed 9 May 2018. ↩

- Special Dispatch to the Baltimore Sun. (1882, Feb 20). The Virginia Oyster War. The Sun (1837-1992). ↩

- The Associated Press. “Saving the Chesapeake.” The Washington Post, Express ed., 28 Feb. 2018, Local sec. ↩