“Pueblo is Shifted by North Koreans: The North Korean moved the captured United States intelligence ship Pueblo from the port of Wonsan to another place, State Department officials said today.” 1

New York Times (AP)

May 10, 1968

Bill Streifer

Freelance Journalist

January 23rd of this year marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Pueblo Incident. On that day in 1968, the naval and air forces of the Democratic Republic of Korea (DPRK) attacked a U.S. Navy intelligence ship with 83 men onboard. When the captain of the ship, Commander Lloyd M. Bucher, surrendered without firing a shot, he became the first U.S. sea commander to do so since 1807. 2 After eleven months of beatings, brutal interrogations, and forced confessions as prisoners of the North Koreans, the crew of the USS Pueblo crossed into freedom across the “Bridge of No Return” at Panmunjom (DMZ). The ship, however, remains on display in Pyongyang, North Korea in what CBS News recently described as a “North Korean propaganda prize.” 3

In a 2013 photo, 4 North Korean leader Kim Jong-un is seen saluting outside of the USS Pueblo (the “Victorious Fatherland War Museum”) prior to a fireworks display marking the 60th anniversary of the July 27th Korean War armistice agreement.

The story of the Pueblo is well-known to everyone interested in Korean contemporary history and the international politics of the Cold War, says Dr. Andrei Lankov, a Professor of History at Kookmin University in Seoul. 5 Born in the Soviet Union and a graduate of Leningrad State University, Lankov is considered one of the world’s leading authorities on North Korea. 6 He also attended Kim Il-sung University in Pyongyang, 7 In his article on the Pueblo Incident, “The Pueblo as a North Korean Monument,” Lankov remarked how the Pueblo, the only U.S. Navy ship held captive by a foreign government, 8 was “now ranked among the greatest monuments found in Pyongyang.” 9 And in the article’s subsection titled, “A Ship Resurfaces,” Lankov mentioned how the North Koreans had “hidden” the Pueblo at some undisclosed location, before it surprisingly reappeared in Pyongyang decades later:

In 1995, the Pueblo, hitherto safely hidden (and perhaps disguised) at some naval base, reappeared in public. The ship was moved to the East Coast city of Wonsan, a place near to where it was captured. It was held there for a few years, but in 1999 it suddenly disappeared, only to reappear on the banks of the Taedong River, in downtown Pyongyang (in 2013 it was moved to its current location).” 10

CREW MOVED, PAPER SAYS

About two weeks after the crisis in North Korea began, the New York Times reported that the crew of the Pueblo were moved to a point near the South Korean border “apparently in preparation for their return to American hands,” 11 and how the men would “remain at Kaesong pending the outcome of negotiations.” 12 According to an informed official source, two Korean newspapers in Seoul 13 reported that the crew was presented to the North Korean public at a rally in Pyongyang on February 8th. 14 The date of this stunt—corresponding to the 20th Anniversary of the founding of the North Korean Army—was clearly chosen for propaganda purposes. 15 The next day, the captive crewmen were transported by train from Pyongyang to Kaesong, a North Korean village six miles northwest of Panmunjom where negotiations for the release of the ship and crew had already begun. 16

Quoting an (optimistic) unidentified informant, the South Korean press reported that North Korea would return the body of the dead seaman and the wounded men “within a few days,” 17 Through neutral negotiations, the Americans were informed that one member of the crew was killed and three others injured, one seriously, during the ship’s capture. 18 It was later learned that Marine Sergeant Robert Chicca had a hole the size of a silver dollar in his upper thigh 19 and that Fireman Steven Woelk was seriously wounded in the lower abdomen. 20 Worst of all was Fireman Duane D. Hodges, the crewman who died, when a 57-mm shell from North Korean cannon fire caught him almost squarely in the groin, ripping his intestines open and partially severing his right leg. 21

About three months into the crisis in North Korea, Nicholas Katzenbach, President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Attorney General, testified in executive session on the Pueblo Incident before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee—Senator J. William Fulbright, Chairman of the Committee, presiding. 22 Katzenbach began by saying he hadn’t prepared a statement. “That is fine. I prefer it that way,” Fulbright said. “Just give us a little rundown in the situation in Korea and then the situation with respect to the Pueblo…” 23 First, the Attorney General asked for a few minutes to discuss the general situation in Korea before the current crisis erupted. 24 “I do not mean to be alarming in any way,” Katzenbach said, “but I think it is a situation that does give concern.” 25

For the last year and a half, the North Korean line had been “very tough indeed in terms of their public statements.” 26 Beginning in October 1966, Kim Il-sung, the leader and founder of North Korea, talked about unification; he talked about revolution in South Korea; and he called for joint action against U.S. forces. 27 This was accompanied, Katzenbach said, by “similar statements on an increased level.” 28 As recently as April 24, 1968 (post-seizure of the USS Pueblo), Kim Jong-il (Kim Jong-un’s father), the First Vice Premier of North Korea, talked about “the huge job of completing the revolution” and uniting North and South Korea. 29 He also said “war might break out at any moment in Korea,” 30 and they were taking “full measures to crush the U.S. imperialists, and so forth,” 31 Katzenbach said.

With respect to the Pueblo, the Attorney General told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that the Americans had engaged in private discussions with the North Koreans, without the presence of others, at fifteen meetings over a period of time. 32 “They have not been accompanied with a great deal of diatribe,” Katzenbach said. “I suppose that part. at least initially, we took as encouragement. On the other hand, they have gotten really virtually nowhere.” 33 During all meetings, the North Koreans were adamant: “You won’t get the Pueblo back.” 34 And before the North Koreans would consider releasing the crew, Katzenbach said, the Americans would first have to apologize publicly for their espionage activities and unlawful mission, as well as for their multiple intrusions into what the North Koreans claimed was North Korean territorial waters, 35 crimes for which the North Koreans said several members of the Pueblo crew, including the captain of the ship, had already “confessed.” 36 They had not even gone so far as to say, “If you do this, you will get the crew back.” 37 Instead, they said, “You do that, and that is an essential precondition to get back the crew. You won’t get the vessel back in any event.” 38 By then, the Pueblo was no longer in the Wonsan area, fearing the Americans might try to drag the American spy ship out. North Korea’s concern was justified.

When the Pueblo Incident began, President Johnson considered a dozen or more “possible actions” he could take in response to the North Korean seizure of the U.S. Navy vessel. One [Action No. 4] called for a show of force led by the USS Enterprise (CVN-65), a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier. 39 Another [Action No. 3] involved a diplomatic demand coupled with a tug that could drag the Pueblo out, if necessary. 40 To add meaning and force to the diplomatic demand, the plan called for a flag ship to arrive “peacefully and unarmed” at Wonsan, where the U.S. Navy ship was seized. 41 The intent of Action No. 4 was to demonstrate to the world “our determination and emphasize our insistence on prompt return.” 42 Also strongly implied was that force would be used unless the ship was returned safely. 43

With these goals in mind, the plan called for a U.S. Navy sea-going tug to steam to Wonsan to accept the return of the captured ship and crew. 44 Meanwhile, a carrier task force “over the horizon” would be available just in case. 45 Although it was believed the Pueblo could proceed on its own power, the tug would be available to accept custody and tow if need be. 46 The use of a tug, rather than a warship, would “display determination, confidence, and peaceful intent.” 47 If the tug met hostile action, however, “quick word to task forces would provide support.” 48

RD3 John L. Perry, a radarman aboard the USS Truxtun (DLG 35), recalls the plan to pull the Pueblo out differently—neither peacefully nor unarmed. 49 According to Perry, the Truxtun, along with the Halsey, were ordered to escort the Enterprise to Korea in retaliation for the seizure of the Pueblo. 50 However, when the Enterprise and Truxton received orders to proceed to North Korea, they were more than 500 miles from Wonsan. 51 To make things worse, only 35 of the 59 fighter jet aircraft on board the Enterprise were operational. 52

When the Truxtun pulled out of Sasebo, Japan at around 9 o’clock that morning, it was heading south toward the Philippines. 53 Then, during evening chow, Perry recalled that the ship heeled over in a sharp, table-clearing 180-degree turn, as the voice on the 1MC [the ship’s primary public address system] informed the crew of the Truxtun that an unnamed U.S. Navy vessel was captured by the North Koreans, and “we were going to assist, if possible.” 54 Meanwhile, the Enterprise and its screening ships were ordered to reverse course in the East China Sea and to run northward to the Sea of Japan as the Truxtun headed north at flank speed (about 33 knots) with the Enterprise and Halsey trailing behind. 55 Unlike the Halsey, the nuclear-powered Truxtun was fast and didn’t require refueling by the Enterprise, so it pulled steadily ahead of the other ships. 56

At around 4am the next morning, Perry said they received orders to rig up towing cables, and to be ready to go into Wonsan Harbor during the daylight hours. 57 They were going to “shoot the place up, recapture the Pueblo, and tow it out of there, 58 Perry said. However, with only one 5-inch/54 caliber and two 3-inch/50-caliber anti-aircraft guns, and an aluminum superstructure and thin skin, Perry figured they had their work cut out for themselves if the Truxton was to get into a gunfight with North Korean shore batteries. 59

By 5am, the Truxtun had pulled up just south of Wonsan, and an hour later, two older WWII-vintage destroyers arrived on station and were given the towing assignment, which was set to begin at 8am. 60 But the plan was postponed until 9, and then 10. 61 Perry said the recovery effort was eventually called off, either because they felt the Pueblo was a lost cause; or because the crew of the Pueblo had already been taken off the ship; or because the secret material on board had already been compromised. 62

SEARCHING FOR THE PUEBLO

On March 18, 1965, John McCone, the new Director of Central Intelligence, discussed with Secretaries Robert McNamara and Cyrus Vance the increasing hazards to U-2’s and the drone reconnaissance of Communist China. 63 Four days later, Brigadier General Jack C. Ledford, Director of the Office of Special Activities, briefed Vance on the scheme which had been drawn up for operations in the Far East. 64 The project was called BLACK SHIELD. 65

Between January 1, 1968 and the end of March, fifteen CIA “BLACK SHIELD” reconnaissance missions were alerted (scheduled) for flights over Communist targets. 66 The mission vehicle was the Lockheed A-12 “Archangel,” capable of photographing targets on the ground from an elevation of 10,000 feet and Mach 3.5 (three and a half times the speed of sound). Of the six missions actually flown, four were over North Vietnam and two were over North Korea. 67 Eight of the others were cancelled due to the weather, and the approval of one, for a flight over Korea, wasn’t obtained. 68

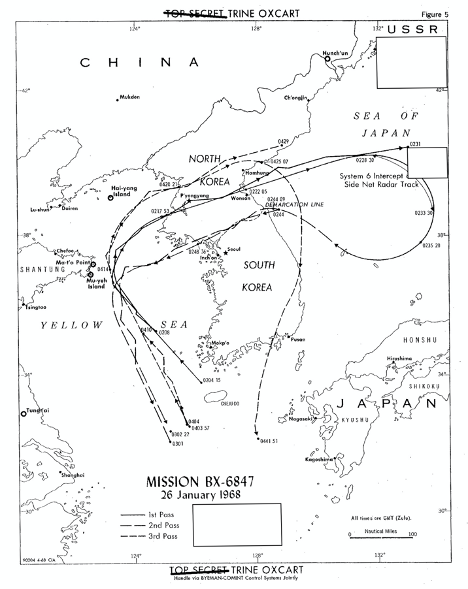

To determine the Pueblo’s current location, BLACK SHIELD Mission BX-6847 was flown over Wonsan on January 26; that was three days after the seizure of the Pueblo and one day after approval was granted for this reconnaissance flight. 69 The pilot’s name was Jack W. Weeks. His A-12 mission over North Korea was tracked by radars of the Chinese Air Defense System 70 and by Soviet air defense radars for about five minutes. 71 [The mission’s 3-pass flight path is seen in Appendix I] A photograph taken during this mission (See below) shows the Pueblo at anchor in Wonsan Bay. 72 The CIA said this mission demonstrated the BLACK SHIELD program’s ability to react rapidly.

In addition to the immediate task of locating the Pueblo, these A-12 flights also photographed North Korean industrial and transportation systems. 73 The mission also provided an updated order of battle for North Korea 74 (military units, formations, and equipment). During BLACK SHIELD Mission BX-6847, for example, the A-12 photographed dozens of North Korean COMIREX [Committee on Imagery Requirements and Exploitation] targets and 837 bonus targets. 75 In addition to the Pueblo, three new guided missile patrol boats were observed. 76

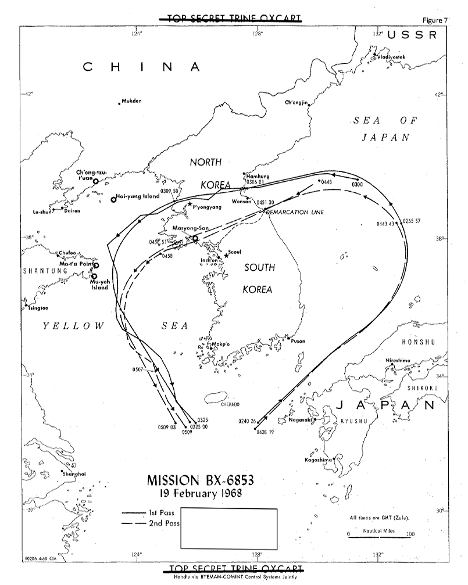

A second BLACK SHIELD mission was flown on February 19, 1968. The CIA spy pilot’s name was Frank Murray. 77 During Murray’s Mission BX-6853, 84 North Korean COMIREX targets and 89 bonus targets were photographed, 78 and in the vicinity of Wonsan, one new occupied Soviet SA-2 surface-to-air missile site was identified. 79 [The mission’s 2-pass flight path is seen in Appendix II]

In terms of this mission’s ability to photograph the Pueblo, however, it was hardly as successful as the first. Scattered clouds covered 20 percent of the area photographed, concealing the area where the Pueblo had been photographed previously. 80 Was the Pueblo “hidden,” just as Dr. Lankov said, or was it merely hidden from view due to excessive cloud cover? 81 All the CIA knew at the time—nearly a month after the Pueblo Incident began—was that the Pueblo had “reportedly” been relocated. 82

Two days later, in a top secret memorandum addressed to Richard Helms, the Director of Central Intelligence, with the subject line: “Location of the Pueblo,” Dr. William A. Tidwell, 83 the Chairman of COMIREX, 84 floated the idea of adding A-12 flights over North Korea. 85 “As a result of the last BLACK SHIELD mission,” Tidwell wrote, “it seems clear that we do not know the location of the Pueblo.” 86 Since COMIREX wasn’t scheduled to obtain assistance from satellite reconnaissance for the purpose of finding the Pueblo, 87 if the location of the Pueblo was “of critical importance in U.S. policy decisions during the next month,” Tidwell suggested that “the only feasible way of searching for its present location would appear to be to employ the OXCART” (code name for the A-12). 88 Tidwell’s memo concluded as follows: “We will be prepared to provide coordinated requirements as rapidly as possible if you decide at any point that the location of the Pueblo is of such importance as to justify another OXCART mission.” 89

Between April 1 and June 9, 1968, only two BLACK SHIELD missions were alerted, both for flights over North Korea. The first, BX-6857, scheduled for April 27, was cancelled. 90 The other, BX-6858 (scheduled for May 5th), was flown on May 8th. 91 The pilot’s name was Jack Layton. [The mission’s 2-pass flight path is seen in Appendix III] Hampered by clouds and heavy haze, this third and final OXCART mission over North Korea revealed no significant changes in North Korean military posture or disposition, 92 and coverage of the DMZ, transportation, and infiltration routes disclosed no significant troop build-up of logistic movements. 93 During the mission, 68 COMIREX targets plus 30 bonus targets were photographed, 94 fifteen of which were SA–2 surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites. 95 Also identified was a possible Soviet-made SAMLET coastal defense cruise missile site, located between Wonsan and Hamhung. 96

Unfortunately, overcast conditions severely hampered the interpretability of mission photography. 97 A report on BLACK SHIELD reconnaissance missions by the CIA’s Directorate of Science and Technology, stated: “Existing weather conditions in the target area did not permit the photographing of the USS Pueblo,” 98 nor was there any indication of a hostile weapons reaction. 99 Air surveillance tracking was accomplished by elements of the Chinese Air Defense System (ADS), but there was no indication of tracking by either North Korean or Soviet ADS. 100 Apparently, neither the North Koreans nor the Soviets paid much attention to this May 8, 1968 mission over Wonsan. Two questions remain: Had the North Koreans already moved the Pueblo out of harm’s way and where was the Pueblo now?

“IT SEEMS CLEAR THAT

WE DO NOT KNOW THE LOCATION OF THE PUEBLO”

A few days after the conclusion of the third and final BLACK SHIELD mission, the press reported for the first time that the Pueblo was no longer in Wonsan Harbor. In “Koreans Move Pueblo,” the Washington Post said that the State Department confirmed that the North Koreans had moved the USS Pueblo from where it was seized back in January. 101 The officials who provided this information declined to provide further details except to say that the vessel was moved without its American crew. 102 At the time. the U.S. had repeatedly called on North Korea to return the Pueblo and its men without result. 103 According to the New York Times, the surviving crewmen were still being held, possibly in several places. 104

The Washington Post further reported that it was Winthrop G. Brown, a former U.S. Ambassador to South Korea and currently a special assistant to Secretary of State Dean Rusk, who had disclosed—during a closed session of the House Foreign Affairs Committee—that the Pueblo had been moved. 105 State Department Officials would only confirm Brown’s testimony, declining to provide any further details publically 106 Some members of the Committee, however, thought the Pueblo might have been taken to the North Korean city of Chongjin which the Washington Post said was “nearer the Soviet border.” 107 Joseph C. Goulden of the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Washington Bureau provided another clue. In “Spy Satellite Spots Removal of USS Pueblo,” Goulden said that photos showing the Pueblo was no longer at the berth she occupied ever since her capture were taken by “one of the satellites that make regular sweeps over the Asian mainland.” 108

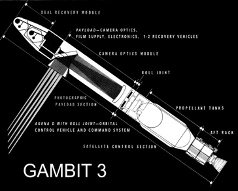

What the Government knew all along, but failed to disclose to the public, was that a GAMBIT 3 high-resolution photoreconnaissance satellite 109 had spotted the Pueblo in the waters off Vladivostok (USSR) at least a month earlier. On April 24, Dr. John S. Foster, Jr., an American physicist who had served as the Director of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, testified in closed session before the Senate Subcommittee on Military Preparedness. 110 As Director of Defense Research and Engineering who managed the Defense Department’s $8 billion research and development budget, U.S. Senator John C. Stennis said Dr. Foster played a “key role in the policy decisions which determine the quality of our nuclear strategic arsenal.” 111

In his opening statement (prepared by Dr. John Kirk, Assistant Director for Space Technology, on the April 12th), Dr. Foster said he welcomed the opportunity to discuss U.S. strategic nuclear policy and capabilities, and that his lengthy written statement, which he presented to the Senate Subcommittee, would cover three areas. 112 First, the general strategic situation for the next few years and U.S. national security objectives. 113 Second, our nation’s research and development philosophy and the guidelines for managing R&D on strategic programs. 114 And lastly, Foster said he would review for the Senate several major weapons systems issues, including a new missile, an advanced bomber, an air defense interceptor, and missile defense. 115

Dr. Foster also explained how, by means of the higher resolution of 12-18 inches, 116 the KH-8, or Keyhole, satellite was “used to provide engineering details which allow us to ‘Baseline’ equipment and probable usage of thousands of specific national targets within the Soviet Union and China.” 117 First launched in 1966, the GAMBIT 3 118 (KH-8) satellite camera system 119 provided the U.S. with an “exquisite surveillance capabilities from space.” 120 The GAMBIT, along with the U-2, A-12, and other air and space platforms, propelled the United States into an unparalleled position of dominance in photoreconnaissance capabilities, which the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) said helped the U.S. win the Cold War. 121

Among the targets Dr. Foster mentioned during his testimony included missile silos (starts and types), nuclear storage sites and facility changes, Chinese nuclear test build-up, and underground nuclear test craters in the USSR. 122 He also revealed that a KH-8 camera had “located USS Pueblo in North Korea about 19 miles south of Vladivostok…” 123 After learning of this information, Frank Murphy, the CIA spy pilot who flew his A-12 over Wonsan, North Korea in February 1968, wrote, “I did not know that Pueblo was moved to a place near Vladivostok.” 124

Following the North Korean seizure of the Pueblo, Soviet experts grabbed encryption machines and the top secret documents on board. So by the time the North Koreans moved this U.S. Navy spy ship up the coast, it was of no further value to the Soviet Union. Why, then, did the North Koreans elect to send the ship into the waters off Vladivostok, the main naval base of the Soviet Far East? This remains one of the unanswered questions surrounding the Pueblo Incident.

Appendix I

(Mission BX-6847 Flight Path — January 26, 1968)

Appendix II

(Mission BX-6853 Flight Path— February 19, 1968)

Appendix III

(Mission BX-6858 Flight Path — May 5, 1968)

Footnotes

- “Pueblo is Shifted by North Koreans,” New York Times, May 10, 1968, p. 5. ↩

- Cheevers, Jack, “The Pueblo Scapegoat,” Navy History Magazine, Vol. 28, No, 5, Oct. 2014. ↩

- “USS Pueblo Displayed as North Korean Propaganda Prize,” CBS News, Pyongyang, North Korea: Jan. 25, 2018; https://www.cbsnews.com/news/uss-pueblo-displayed-as-north-korean-propaganda-prize. ↩

- In 2016, the photographer, Giles Hewitt (a British national born in India), was named Asia-Pacific editor of L’Agence France-Presse (AFP). Four years earlier, Hewitt became AFP’s Seoul bureau chief whose responsibilities included covering news out of North Korea where AFP recently became one of the few foreign media outlets to open a news bureau; https://www.afp.com/en/agency/press-releases-newsletter/appointments afp-1 ↩

- Lankov, Andrei. “The Pueblo as a North Korean Monument,” NKNews.org, Nov. 3, 2014. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “USS Pueblo Displayed as North Korean Propaganda Prize,” CBS/AP, Jan. 25, 2018. ↩

- Lankov, Andrei. “The Pueblo as a North Korean Monument,” NKNews.org, Nov. 3, 2014. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Trumbull, Robert, “Crew Moved, Papers Say,” New York Times, Feb. 10, 1968, p.12. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- The Dalhan Ilbo and the Shin-a Ilbo. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “On Watch: Profiles from the National Security Agency’s Past 40 Years,” Top Secret (classified by multiple sources), 1984 (approved for release by NSA on Sept. 10, 2007), p. 72. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “Briefing on Site Negotiations and the Pueblo Incident,” U.S. Senate, Committee on Foreign Relations, May 1, 1968 (The briefing began at 4:05pm), p. 473. ↩

- “Briefing…,” p. 473. ↩

- “Briefing…,” p. 487. ↩

- “Briefing…,” p. 487. ↩

- “Briefing…,” p. 487. ↩

- “Briefing…,” p. 487. ↩

- “Briefing…,” p. 487. ↩

- “Briefing…,” p. 487. ↩

- “Briefing…,” p. 487. ↩

- “Briefing…,” p. 487. ↩

- “Briefing…,” p. 489. ↩

- “Briefing…,” p. 489. ↩

- “Briefing…,” p. 489. ↩

- “Briefing…,” p. 489. ↩

- “Briefing…,” p. 489. ↩

- “Briefing…,” p. 489. ↩

- “Briefing…,” p. 489. ↩

- “Index of Possible Actions.” Undated. Top Secret. 35 pp. Source: National Archives, RG 218, Records of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Records of Chairman (Gen.) Earle G. Wheeler, 1964-1970, box 29, tab 449. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- RD3 John L. Perry; http://www.usspueblo.org/guest_comments/Guests_2000.htm (blog), Feb. 5 2000. ↩

- Also sent were battleships and two additional aircraft carriers, as part of a task group code-named “FORMATION STAR.” The Joint Chiefs also recommended that nine submarines be sent to support reconnaissance and potential attack missions. [Mobley, Richard, Flash Point North Korea: The Pueblo and EC-121 Crisis, Naval Institute Press, 2003 ↩

- Michishita, Narushige. Calculated Adventurism: North Korea’s Military-Diplomatic Campaigns, 1966-2000, Johns Hopkins University, 2003, p. 307. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- John L. Perry, http://www.usspueblo.org blog, Feb. 5, 2000. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/kent-csi/vol15no1/html/v15i1a01p_0001.htm ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD Reconnaissance Missions, 1 January – 31 March 1968,” DST-BS/BYE/68-2, CIA, Directorate of Science and Technology, Top Secret, Apr. 20, 1968; approved for release, Aug. 2007, p. 1; after an MDR appeal, redactions were removed by ISCAP on Sept, 19, 2016. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD Reconnaissance Missions, 1 January – 31 March 1968,” p. 1. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD…March 1968,” p. 2. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD…March 1968,” p. 2. ↩

- This image is a collage of photos taken from declassified CIA documents; Streifer, Bill. “Anything Could Happen: Newly Declassified CIA Documents Tell an Entirely Different North Korea ‘Pueblo Incident’,” North Korean Review 12(2), Oct. 2016. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD…March 1968,” p. 1. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD…March 1968,” p. 1. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD…March 1968,” p. 8. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD…March 1968,” p. 8. ↩

- The author interviewed Frank Murray in February 2018. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD…March 1968,” p. 11. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD…March 1968,” p. 11. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD…March 1968,” p. 11. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD…March 1968,” p. 11. ↩

- “Implications of Reported Relocation of USS Pueblo,” CIA Intelligence Information Cable, February 12, 1968, Declassified Documents Reference System, doc. no. CK3100137943. ↩

- Typically, the Chairman’s name is redacted from top secret CIA documents, but not from the following top secret NRO document: “Program for Planning the Exploitation of Reconnaissance Imagery,” memorandum for COMIREX, Sept.25,1968 (Approved for release by the NRO on July 1, 2015). Dr. Tidwell. Years earlier, Dr. Tidwell also played a role in the Cuban Missile Crisis. ↩

- “Location of the Pueblo,” memorandum the Chairman, Committee on Imagery requirements and Exploitation, to the Director of Central Intelligence, Feb. 21, 1968. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Ibid ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD Reconnaissance Missions, 1 April – 9 June” (Appendix I), p. 5. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD Reconnaissance Missions, 1 April – 9 June ,” p. 1. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD Reconnaissance Missions, 1 April – 9 June ,” p. 1. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD Reconnaissance Missions, 1 April – 9 June ,” p. 1. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD Reconnaissance Missions, 1 April – 9 June ,” p. 2. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD Reconnaissance Missions, 1 April – 9 June ,” p. 2. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD Reconnaissance Missions, 1 April – 9 June ,” p. 2. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD Reconnaissance Missions, 1 April – 9 June ,” p. 2. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD Reconnaissance Missions, 1 April – 9 June ,” p. 2. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD Reconnaissance Missions, 1 April – 9 June ,” p. 2. ↩

- “BLACK SHIELD Reconnaissance Missions, 1 April – 9 June ,” p. 2. ↩

- “Koreans Move Pueblo,” Washington Post, May 10, 1968, p. A-23. ↩

- “Pueblo is Shifted by North Koreans” (AP), New York Times, May 10, 1968, p. 5. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “Koreans Move Pueblo,” Washington Post, May 10, 1968, p. A-23. ↩

- Goulden, Joseph C. “Spy Satellite Spots Removal of USS Pueblo,” Philadelphia Enquirer, Inquirer Washington Branch, May 10, 1968, pp. 2-3. ↩

- “Koreans Move Pueblo,” Washington Post, May 10, 1968, p. A-23. ↩

- Goulden, Joseph C. “Spy Satellite Spots Removal of USS Pueblo,” Philadelphia Enquirer, Inquirer Washington Branch, May 10, 1968, pp. 2-3. ↩

- This high-resolution illustration of a GAMBIT 3 satellite was obtained through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request from the NRO [F-2018-00050 ↩

- “Intelligence Information for Dr. Foster’s Appearance Before the Senate Subcommittee on Military Preparedness” (opening statement by Dr. John Kirk), Apr. 11, 1968 (Approved for release by the NRO on July 1, 2015), 5 pgs. ↩

- “Status of U.S. Strategic Power,” U.S. Senate, Preparedness Investigating Subcommittee of the Committee on Armed Services, Wednesday, Apr. 24, 1968, p. 45-46. ↩

- “Status of U.S. Strategic Power,” U.S. Senate, Preparedness Investigating Subcommittee of the Committee on Armed Services, Wednesday, Apr. 24, 1968, p. 45-46. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “Intelligence Information for Dr. Foster’s Appearance Before the Senate Subcommittee on Military Preparedness,” Approved for release on Feb. 21, 2018. ↩

- “Intelligence Information for Dr. Foster’s Appearance Before the Senate Subcommittee on Military Preparedness” (opening statement by Dr. John Kirk), Apr. 11, 1968 (Approved for release by the NRO on July 1, 2015), 5 pgs. ↩

- The photo of the GAMBIT 3 satellite was obtained from the NRO through a FOIA request on February 13, 2018. ↩

- SPECS: 28.6 feet long, 5-feet in diameter with a focal length of 175 inches ↩

- http://www.nro.gov/history/csnr/gambhex/Docs/Hex_fact_sheet.pdf ↩

- Clausen, Ingard & Miller, Edward A Miller, “Intelligence Revolution 1960: Retrieving the Corona Imagery that Helped Win the Cold War,” Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance, April 2012. ↩

- “Intelligence Information for Dr. Foster’s Appearance Before the Senate Subcommittee on Military Preparedness” (opening statement by Dr. John Kirk), Apr. 11, 1968 (Approved for release by the NRO on July 1, 2015), 5 pgs. ↩

- Though declassified in 2015, portions of Dr. Foster’s testimony remains heavily redacted; “Intelligence Information for Dr. Foster’s Appearance Before the Senate Subcommittee on Military Preparedness” (opening statement by Dr. John Kirk), Apr. 11, 1968 (Approved for release by the NRO on July 1, 2015), 5 pgs. ↩

- Frank Murray, Feb.18, 2018. ↩