James P. Ransom III

Independent Historian

There exists a misperception of submarines as self-sufficient hunters, prowling the seas and conducting their operations with little oversight, using only the cunning of their commanding officers and resourcefulness of their crews to perform their mission. But the reality is that despite the independent nature of their operations, American submarines in the Second World War, with their cramped living and working conditions and small crews, required significant support from a shore staff of senior personnel with technical and operational submarine expertise.

In pre-war Manila, home of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, the squadron commander and a small staff provided this support . They were embarked aboard submarine tender Canopus, which spent the majority of her time in port, brimming with repair and logistics experts, with access to the naval repair facility and logistics hub at Cavite Navy Yard. The squadron commander was responsible for directing the operations of the Asiatic Fleet’s submarines on behalf of the fleet commander. He and his staff oversaw the training and material condition of their assigned submarines and crews, and controlled the communications that facilitated their operations. Once hostilities commenced, they established the operational deployment plan for their submarines to achieve strategic effects, provided them with intelligence and information concerning events in theater, and provided the fleet commander with reports sent from submarines in their patrol areas, in order to help bring clarity on the overall strategic picture. When they ordered the submarines into port, they ensured the replenishment of torpedoes, fuel, spare parts, and food, and organized vital repairs. They collected and disseminated lessons learned from recent operations, and certified the submarines ready for their next underway period. The submarines could not perform their duties without this vital organization.

In evaluating the senior leadership of Asiatic Fleet submarines, two officers stand out for leading their force in challenging circumstances. Despite the eventual disappointing performance of their assigned submarines, these men worked hard to perform their duties to prepare their boats for war, to execute their operational plan in the face of adversity, to reassess and adapt as events unfolded, and to make major decisions that affected their force. They carefully evaluated the results reported by commanding officers to recommend changes in operational plans and tactics, and sometimes to relieve skippers who did not meet their standards of performance.

This is a story of tenacity in the face of daunting challenges, with few successes and many failures. However, their efforts were significant to the eventual improvement in performance of U.S. submarines in the war after the rocky start.

Asiatic Fleet Submarines and Personnel Prepare for War

Manila had the largest concentration of modern American submarines in December 1941.1 Admiral Thomas C. Hart was the Asiatic Fleet commander (CinCAF), and had been associated with submarine torpedoes, operations, and design since before the First World War. He had high hopes for their success.

Commander John E. Wilkes, U.S. Naval Academy Class of 1916, was the senior submarine officer under Hart on the Asiatic Fleet staff. He was tall and tough, an excellent athlete in college. He was described as being “somewhat of a martinet,” with a stern and irascible demeanor.2 Wilkes commanded one of the first prototype fleet boats and a submarine division in Manila in 1939 before assuming command of the squadron there.

Following his arrival as CinCAF in 1939, Hart had steadily increased the number of submarines assigned to his small fleet from six to seventeen, including the first modern fleet-type boats. As the war clouds gathered in November 1941, another squadron of twelve modern fleet boats with their submarine tender Holland sailed into Manila Bay from Pearl Harbor as reinforcements. Their arrival created something of an organizational dilemma. Wilkes was due to rotate back stateside, and Hart could ill-afford to lose his experience and knowledge of Western Pacific operations, the boats, and the skippers. His designated relief, Commander James Fife Jr., USNA 1918, had just reported. However, Fife was significantly junior to Captain Walter E. Doyle, USNA 1913, who commanded the newly arrived Submarine Squadron Two. Doyle had worked for Hart in the mid-1930s at the Naval Academy when Hart was Superintendent. He had commanded a fleet boat and Holland, but otherwise had an unremarkable career. Hart had never been impressed with him.3

By navy convention, as the senior submarine officer, Doyle should relieve Wilkes. But Hart had misgivings. His solution was to have Fife, a cerebral and highly respected submariner, serve as Doyle’s chief of staff. Fife had served as a naval attaché to Great Britain in 1940-41. In that billet he had directly observed much of the naval war in the Mediterranean during his travels, including embarking Royal Navy submarines on war patrols. After returning to the U.S. from this tour, he visited U.S. Navy commands to present his observations. He went to Manila in June 1941, where he briefed Hart and his staff, and hand-carried to him the new Rainbow Five war plans.4

The arrival of Doyle’s squadron gave Hart’s submarine force twenty-three modern fleet boats and six elderly S-Class boats. He decided an organizational change was required for the war that he believed was imminent. He dissolved the administrative structure of two submarine squadrons, each with multiple divisions. The new organization was designated Commander Submarines, U.S. Asiatic Fleet (CSAF). With the submarines now the Asiatic Fleet’s most powerful striking force,5 the reorganization would optimize the focus on supporting wartime operations.

On December 1st, the day that CSAF was officially established, Doyle relieved Wilkes and assumed responsibility for all U.S. submarines in the Far East. Hart ordered Wilkes to remain in the Philippines, eying the deteriorating strategic situation with Japan and looking to maintain an ace in the hole. His final piece to the submarine leadership puzzle was to have Wilkes stay on as a “special advisor” to CSAF.6 The new submarine commander would have the support of Wilkes, Fife, and five former submarine division commanders—three with significant experience in the Far East and two who had come along with Doyle. All were post-command officers of high abilities.

CSAF deployed two S-boats on 2 and 3 December: S-36 to Lingayen Gulf, where planners had long expected the Japanese would eventually land in force once war erupted, and S-39 to Sorsogon Bay to provide overwatch on the strategic San Bernadino Strait. The other twenty-seven boats sat in port on the evening of 7 December as everyone awaited Japan’s next move. It was clear that the Japanese were moving, as reports of ship movements southward were received. But where this blow would land was the subject of conjecture: would it be aimed at Thailand, or against British Malaya, or even directly at the Dutch East Indies? And how would the Japanese choose to deal with the United States and its territory of the Philippines?

A Most Tumultuous Campaign

On 8 December, the Japanese simultaneously struck multiple locations throughout the Far East. Landings occurred on Thailand’s Kra Isthmus aimed at driving into Malaya, and other forces attacked Hong Kong. They also landed on the Philippine island of Batan north of Luzon, and hammered at American airpower on Luzon and Mindanao. Their initial air attacks decimated General Douglas MacArthur’s air forces. As a result, the enemy was able to operate over the Philippines and surrounding seas with little opposition from American air power. Hart immediately sent a radio message to his fleet to commence unrestricted air and submarine warfare against Japan.

CSAF immediately deployed seven submarines off Japanese naval bases in Formosa, Hainan, and Indochina, ten boats to the north and east of Luzon and in the inter-island waters south of Luzon, and six boats in defensive areas on the west coast of Luzon. By 11 December, twenty-three submarines were at sea for operations against the enemy.

On 10 December Hart directed Doyle to turn command of CSAF back to Wilkes, ordering Doyle to take tenders Otus and Holland and several other ships to escape south. The implication was clear: Hart had not been satisfied with Doyle’s performance in command. He stated that it was “no time for [a] green boss.”7 Doyle had been insecure in Hart’s presence. While the staff should have been getting into a rhythm with their new organization, instead they wasted half their day preparing Doyle for disastrous meetings to brief Hart.8 Later on, the 10th Japanese bombers appeared in the empty skies over Manila. With unhurried precision they destroyed the Cavite Navy Yard, sinking submarine Sealion and damaging Seadragon.

Back in command, Wilkes split the CSAF staff into two teams. He led one group while Fife led the other. They shared duties around the clock—port and starboard watches in navy parlance—to monitor, direct, and support the operations of their submarines. With so many submarines at sea, someone had to be on watch at all hours to respond to the boats and direct their operations. With Japanese aircraft controlling the skies, the CSAF staff moved ashore from Canopus to take over the abandoned former Enlisted Men’s Club. Wilkes observed, “You could have set your watch” by the hour of the daily arrival of Japanese planes, and his men raced for slit trenches outside the club as bombs rained down.9 The bombing raids also forced the submarines in Manila Bay to bottom during attacks, disrupting repairs and provisioning, and further exhausting the crews. Without air protection, the days of operating submarines from Manila were numbered.

John Wilkes and Jimmy Fife had very different temperaments and leadership styles. Wilkes was more tightly wound, but still respected for his knowledge and leadership. Fife was described as being supremely dedicated to his work, and one of the hardest working and best prepared officers anyone knew. Wilkes was known to enjoy a drink with his staff, while Fife was a teetotaler. While he could be stern, Wilkes was said to also have a human side to him. Fife, on the other hand, was described as being “without warmth.” Hart thought very highly of both these officers.10

American submarines tried desperately to derail the carefully planned and skillfully executed Japanese operational scheme to encircle the Philippines. Landings at Vigan and Aparri in northern Luzon on 10 December and at Legaspi in southeastern Luzon on the 12th were just preliminaries to the main event. The boats were either late in arriving in the areas or ineffective in disrupting the invading ships. When the main invasion materialized off Lingayen Gulf late on 21 December, Stingray reported the invasion convoy but failed to attack. Wilkes ordered several boats to converge on the gulf and attack, dispensing with area restrictions designed to keep the boats apart to prevent fratricide. But by that time it was too late. Aggressive convoy escorts repelled boats attempting to enter the gulf. Only S-38 was able to penetrate and sink one ship. Wilkes’ submarines failed to attrite or impede the largest enemy invasion convoy of the war.11

As Japanese troops rapidly moved south from Lingayen, MacArthur declared Manila an open city on the 25th. Admiral Hart departed Manila on submarine Shark for Surabaya on the island of Java the next day, looking to prepare for the next phase of the campaign. At the same time, the Japanese were shifting their attention to their main prize, the oil and other resources of the Dutch East Indies.

Meanwhile, some of the boats returning from their initial patrols reported instances of defective torpedoes and attacks that should have produced hits but did not. By the end of December, U.S. submarines had sunk only three Japanese ships.12 After three weeks the submarines had been unable to slow the enemy advances, and worrisome indications of defective torpedoes and missed shots on perfectly set-up short range attacks were becoming apparent to some skippers.

As December came to a close, Wilkes ordered the evacuation of his boats from Manila, taking as many spare parts and torpedoes as they could. His team rode Swordfish south to Surabaya, a major Dutch naval base, while Fife and his team rode Seawolf to Port Darwin, Australia, where Holland had established herself. Fife noted that this was done “so that in case one group was lost…the command could have continued.”13 A week after reaching their destinations, Wilkes ordered Fife and his group to Surabaya to reconstitute the staff.

Prior to departure from the Philippines, Hart and Wilkes had directed how and when the boats should depart their patrol stations in the north and begin repositioning south. The instructions left the decision to depart station in the hands of the skippers. As food and water stocks depleted or material casualties mounted, one by one the boats left their stations to transit south to resupply and prepare for their next patrols.14 This haphazard straggling south would detract from CSAF’s ability to oppose Japanese operations more effectively in the Dutch East Indies.

The shift of the playing field from the Philippines to the Dutch East Indies brought new challenges. There were many seas and straits nestled among thousands of islands, and dangerous reefs were scattered amid the poorly charted waterways.15 Another challenge was coordinating with allies, as the Americans, British, Dutch and Australians had combined their forces under the new ABDA Command. Wilkes’ submariners also now faced an uncertain supply and repair situation.

Submarines would continue operating in and around the Philippines even as the focus changed to defending the Dutch East Indies north of the Malay Barrier. In January submarine patrol days in the South China Sea and around the Philippines still comprised 60 percent of total patrol days on station, but in February it dropped to 10 percent as the action and the boats moved south.

Although Wilkes wanted to focus his forces on the operational challenge of defending the Malay Barrier, political concerns would force him to dilute that effort. In an effort to assuage the War Department, who were responding to requests from MacArthur to supply and reinforce his beleaguered forces in Bataan and on Corregidor, the navy directed Hart to conduct frequent special missions to the Philippines. These submarine missions could only bring in small amounts of ammunition and stores and evacuate limited numbers of personnel, while essentially removing the special mission boat from performing a standard anti-shipping patrol for over a month.

Wilkes felt these requests were not the best use of his forces—he was focused on sinking Japanese ships and disrupting their movement south—but was overridden by higher authority because of the importance placed on the missions. Probably more important than what they brought in was who they brought out, including Philippines President Manuel Quezon and U.S. High Commissioner Francis Sayer and their families, along with vital codebreaking personnel and many army nurses. Asiatic Fleet submarines conducted one special mission to Manila Bay in January, five in February, zero in March, two in April, and one in May just before Corregidor fell.16

Meanwhile, the enemy had the initiative, overwhelming numbers, and command of the air. Geography gifted the Japanese three distinct approaches to Java: from the western side of Borneo; through the Makassar Strait between Borneo and Celebes; and an eastern route through the Molucca Passage east of Celebes.

The Japanese used all three routes to spread out Wilkes’ boats and the rest of the ABDA forces. They kept the submarines off balance, preventing them from concentrating against any one thrust. The Japanese Eastern Force landed in northern Celebes on 11 January, and the Center Force took Tarakan in eastern Borneo the same day. Less than two weeks later they landed at the oilfields of Balikpapan. CSAF had assembled six submarines to contest the landings there, hoping to finally achieve some significant success. But as Fife later said, the failure to sink any ships was “the greatest disappointment that any of us ever had.”17 On the 24th the Eastern Force took the port of Kendari on southeast Celebes.

Submarine Tender USS Holland (AS 3) (NHHC Photo #NH 1098)

As February arrived, the pace quickened. The Eastern Force took Makassar City in southwest Celebes on the 5th, Bali on the 18th, and Timor on the 20th. Massive land-based and carrier-based air raids on Darwin on the 19th made that port unusable. Fortunately the last submarine departed Darwin on 5 February, and Holland had moved to Tjilatjap on the southern coast of Java. By this point Surabaya wasunder bombing almost daily. The Western Force attacked Sumatra on the 14th, and when Singapore surrendered the next day, it was clear where the enemy pincers would converge next.

As ABDA surface naval forces girded themselves for the coming onslaught, CSAF closed defensive submarine patrols into the Java Sea. By late February Wilkes had positioned sixteen boats in the Java Sea and adjacent areas. But the Asiatic Fleet submarines had little effect on the battles of the Java Sea and Sunda Strait in which the ABDA naval forces were thoroughly defeated. The best the submarines could contribute was S-38’s rescue of survivors from a British destroyer.18

Wilkes recognized the need to evacuate the CSAF staff once again, and the eventual retreat of his submarines to Australia. He ordered Fife to take Holland to western Australia to find a suitable submarine base. With Surabaya untenable due to air raids, the boats in refit there and at Tjilatjap proceeded south to Australia, as did other boats returning from lengthy patrols.

It was time to retreat and regroup. CSAF had lost three boats defending the Dutch East Indies: S-36 to grounding on Taka Bakang Reef off Makassar City in January, Shark to attack by probable ant-submarine forces in February, and Perch to destroyers in the Java Sea on 3 March. Wilkes boarded Spearfish on 2 March at Tjilatjap and headed south. By 20 March, nineteen of the remaining twenty-five Asiatic Fleet submarines had arrived at Fremantle, selected as the best location for basing the boats. The boats were repaired and crews received unsatisfyingly brief breathers before going back on patrol, Sculpin being the first to depart on 13 March. Wilkes and Fife were now faced with the task of establishing proper basing and maintenance, a program for providing sufficient crew rest to recover between patrols, and—perhaps most importantly—to determine the lessons of the previous three months.

CSAF Leadership Assessed

An evaluation of Asiatic Fleet submarine leadership includes Hart, as the commander in chief who formulated and executed overall strategy, but also analyzes the control and direction of the Wilkes/Fife team. As CSAF commander and chief of staff, both were integral to decision-making and the smooth operation of the organization during a period of near-constant change. Wilkes of course had the final say, but Fife was an important element of the command process, and during much of the period the two led parallel elements within CSAF to ensure round the clock attention to the needs of their submarines. This assessment must address pre-war preparations, the execution of their responsibilities during the campaign, and how they reassessed and adjusted to improve submarine performance once they had completed the retreat to Fremantle.

Pre-war Preparations

Pre-war factors that reflect on CSAF leadership include training the crews, maintaining material condition of the boats, organizing the staff for success, and preparing an operational plan for war.

Wilkes has been criticized for inadequate training before the war. Much of this is levelled by Clay Blair in his comprehensive and authoritative Silent Victory, but Hart himself vaguely stated of submarine training that it was not “realistic in certain respects.”19 Blair faults Wilkes and Rear Admiral Thomas Withers, the commander of the Pacific Submarine Force at Pearl Harbor, for overseeing unrealistic training. Blair includes a statement by a junior officer aboard Seawolf prior to the war who decried formation steaming exercises overseen by Wilkes during transits that added little value to upcoming combat operations.20 However, although often from the mouths of babes comes truth, they also frequently fail to understand the broader picture. Exactly how much and the type of pre-war training that CSAF required of its submarines is difficult to determine. But the entire fleet spent six weeks operating out of Tawi Tawi in the southern Philippines in the spring of 1941, with significant emphasis on submarine gunnery and torpedo practice, as well as familiarizing the crews with far-flung operating areas. It might have benefitted future operations had Wilkes been able to send a few boats into the Dutch East Indies to get used to the region and bring back some decent charts, but they were likely not planning on an eventual retreat to the south.

Wilkes, like other senior submariners of the time, was very concerned with the threat to submarines from aircraft, urging skippers to conduct submerged approaches from deep using only rudimentary and unreliable sound information to allow for an undetected attack. However, data from Wilkes’ own Action Report indicated less than 7 percent of Asiatic Fleet submarine attacks from December 1941 through March 1942 used sound-only tactics.21 It is clear the skippers were dubious of their chances for a hit in shooting from deep, and shifted to pericope or surfaced attacks. Fear of aircraft also drove CSAF to plan that their boats would operate submerged during the daytime and surface at night for communications and to charge batteries. As a result, skippers remained deep during daylight, thereby severely restricting detection ranges and reducing attack opportunities. The increased submerged operations also slowed their overall speed of advance and increased response time—it took longer for the boats to transit to and from patrol areas or to react to intelligence reports from CSAF.

Wilkes was like most senior submariners in not emphasizing night surface training. This oversight resulted in Japanese anti-submarine forces, superbly trained for night fighting, routinely thwarting night surface approaches and forcing the submarines to relinquish the initiative to submerge and evade. Wilkes also failed to implement pre-war, long-range practice patrols as Withers did for his force. As a result, Asiatic Fleet skippers and crews were unfamiliar with the psychological effects of lengthy onboard confinement. One skipper noted in his post-patrol report that he felt two and three week patrols were at the limit of crew endurance; comments that must have seemed hilarious to crews on later war patrols of 50-60 days.22

Some of his commanding officers thought Wilkes did not pay enough attention to maintenance and the material condition of his boats.23 But repairs were complicated by the long logistics trail from the U.S. to the Philippines. Fife said, “the maintenance and repair in the Philippines had never been completely adequate.”24 It is doubtful that much could have been done to improve the situation.

Hart and Wilkes showed good forethought in restructuring the squadrons for implementation on 1 December into a CSAF organization better able to support wartime operations. But doing so earlier might have allowed the new organization to settle into a good routine rather than having to figure it all out amid the crucible of war. In fairness, many of the key players (Doyle and his division commanders, and Fife) did not arrive in theater until mid- to late-November 1941.

Wilkes and his staff had developed a deployment plan for his submarines before the outbreak of war, such that the orders only required adding boat names and verifying proper routing instructions before presenting them to the commanding officers. The Asiatic Fleet submarine deployment plan was designed to send one-third of the boats across the South China Sea to patrol off Japanese bases on Formosa, Hainan, and Indochina. Another one-third would be assigned defensive patrol areas off the coasts of the main Philippine island of Luzon to oppose any Japanese landing forces that might approach. The final one-third of the boats would be held in reserve to relieve the initial deployers or to be sent where needed as the situation developed. Many of these were sent to “standby stations” to the south of Luzon in the inter-island area.25 As American air power was destroyed early in the conflict and the strategic situation worsened, Hart decided to scrap plans for the reserve force and got as many boats underway as possible.

While the deployment plan was reasonable, Hart should be held accountable for not sending his submarines to sea when war seemed imminent in late November and early December. He should have sent boats to sea for reconnaissance operations or on practice war patrols to get the crews primed for the war he believed was imminent. Some have contended that he was hamstrung by war warning messages that cautioned against an accidental first shot or provoking the Japanese. Hart himself wrote that the submarines “detailed to the offensive positions did not start for their stations before the war began because Washington ordered a ‘defensive’ deployment.”26 But Hart and Wilkes sent submarines to screen transports bringing the Fourth Marines from Shanghai to Manila in late November, which were detected and closely observed by Japanese warships. Their presence provoked great curiosity, but no adverse reactions or trigger-happy incidents.27 I would argue that it was a mistake to have only two boats at sea when the war started. The fleet commander should not have felt his hands were tied by directives from Washington that restricted his ability to protect his force and U.S. national interests. Sending submarines to sea to observe and report while remaining undetected could have provided critical information on Japanese operations and intentions, with the added benefit of having some boats on station when the shooting began.

Leadership During the Campaign

A major failure of submarine leadership occurred on the very first day of the war. As senior officers were briefing skippers prior to getting underway, they counseled them to “use caution and feel their way” on their first patrol.28 One division commander told the commanding officers “Don’t try to go out there and win the Congressional Medal of Honor. The submarines are all we have left. Your crews are more valuable than anything else. Bring them back.”29 Wilkes later sent radio messages to the boats urging aggressiveness to penetrate Lingayen Gulf, but skippers did not press their attempts after meeting Japanese destroyers who detected them and stole the initiative.30 Rather than firing the skippers up to go out and do their utmost to attack and destroy the enemy, a “pep talk” advocating caution set the wrong tone if the desired result was to put Japanese hulls on the bottom.

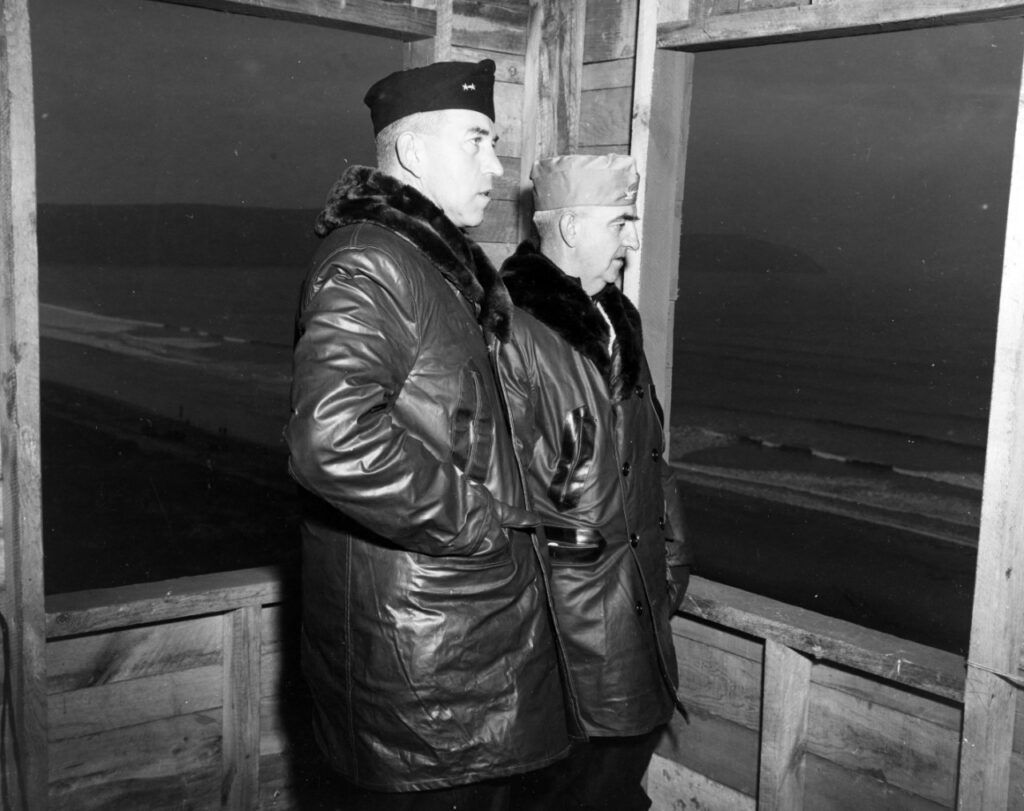

Rear Admiral John Wilkes, USN (left) Watches a dawn landing exercise at Woolacombe, England, on 31 October 1943. With him is Captain Chauncey Camp, USN. (National Archives Photo #80-G-252063)

Once at war, the most important tasks the CSAF staff could address were to provide the boats with intelligence on enemy movements and direct them to areas where they could attack enemy forces. In this they were seriously hindered by the loss of control of the skies early in the war. Without aerial reconnaissance, CSAF lacked the primary means of cuing to best position their assets. This would ensure that Wilkes’ submarines would be, to use a submariner’s term, “chasing the bubble.” They were reactive, not proactive, in their operations. A key indicator of senior leadership lagging behind the problem was that over 60 percent of submarine patrol days in January were still spent in areas around and near the Philippines, even as the Japanese had shifted their offensive to the south against the Dutch East Indies.

Some might argue that the CSAF staff being somewhat out of touch with the operational situation while repositioning to the south during the first week or so of January provides reason for this failure. While true, the real failure was in not taking a more proactive approach to directing some submarines southward before the CSAF staff embarked on Swordfish and Seawolf to head south, once it was apparent the naval campaign for the Philippines was lost. It had been hoped that the submarines would be able to significantly disrupt Japanese landing operations, but once the bulk of the 14th Army was ashore at Lingayen Gulf the leadership should have begun redirecting some of their boats southward in advance of the obvious next phase of the campaign. While it is a natural inclination for the shore commander to want to arrive in the new theater before his submarines and prepare the logistics, in this case it severely hampered the ability to effectively oppose Japanese operations in the Dutch East Indies during the months of January and February.

The staff did a better job of maintaining communications with the boats and supporting their supply and repairs to keep them operating under difficult circumstances. CSAF’s round-the-clock watch organization was generally effective in maintaining control and directing the operations of its submarines. The organization truly excelled in providing the highest quality logistics and repair support possible under extremely dynamic and challenging circumstances. The majority of Wilkes’ staff officers were employed in material support to the boats, with far fewer involved in operations and communications. The staff did an excellent job of directing the tenders to provide voyage repairs and spare parts to the submarines, and in doling out food and precious torpedoes as they prepared for their upcoming war patrols.

One thing the CSAF leadership could not do was give the boats reliable torpedoes. Unacceptable prewar development, testing, and evaluation of the Mark 14 torpedo and the Mark 6 magnetic exploder were to plague the boats throughout the first eighteen months of the war. To Wilkes’ credit, he listened to his skippers and identified the problems to the Bureau of Ordinance in January 1942.31 But they dismissed his concerns, ensuring continued frustration, missed opportunities, and costing the loss of boats and crews.

Wilkes faced some critical decisions during the campaign. He deserves criticism for not sending more submarines into the fight against the Lingayen invasion. However, he showed excellent control and forethought in evacuating from Manila and Java. While forced upon him by necessity, the evacuations were professionally accomplished under difficult circumstances. As previously mentioned, the haphazard manner in which the boats shifted south after the staff evacuated Manila should have been better controlled.

The decision to send boats to operate out of Darwin should have been more carefully considered. Wilkes thought that was where the majority of the boats would be based.32 But its distance from Hart and the ultimate Japanese objective of Java, as well as the lack of consideration for the political implications from the Dutch perspective, led to a rapid reversal to operate out of Surabaya.

One of Wilkes’ more important duties was to ensure his skippers were aggressively pressing attacks to deal damage to the enemy. Those who did not were relieved. During the campaign, Wilkes relieved eight commanding officers; four for lack of results (or what he termed temperamental inaptitude), three at their own request, and one for medical reasons. Although these decisions were closely scrutinized, one skipper stated, “I don’t know a single one who didn’t deserve to be relieved.”33

In general, the submarine leadership was adequate during the initial operations in and around the Philippines and during the retrograde southward to the Malay Barrier and eventually to West Australia. Both Wilkes and Fife demonstrated great energy and dedication, with solid if not inspiring leadership of the staff and good support to their boats. While they made the best of a deteriorating situation, some additional forethought and planning might have yielded better operational results.

Post-campaign Leadership

Once the campaign ended in defeat and retreat to Australia, CSAF adapted quickly, established basing and processes, and began sending boats back on patrol. Wilkes began the search for suitable rest facilities and refit crew procedures to allow for adequate post-patrol recovery for weary submarine crews. But it wasn’t until the arrival of Rear Admiral Charles A. Lockwood in May to relieve Wilkes that this issue was resolved.

What really stands out, however, were the efforts to assess the events of the previous four months and promulgate recommendations and implement changes. Fife “practically locked [himself] up” for a month to write an extraordinary 72-page “Action Report” that was delivered to the Chief of Naval Operations in April 1942.34

The document contained a summary of the campaign, and incorporated the skippers’ perspective based on their individual war patrol reports. It provided a frank assessment and insightful recommendations to operate the submarines with better results in future operations. The report credited the Japanese for their anti-submarine measures, raised concerns about torpedo performance, discussed submarine commanding officer performance issues, recommended submarines patrol along shipping lanes rather than at departure and destination points, and proposed upgrading the boats with important alterations, including surface search radar and reducing sail silhouette to improve night surface detectability. But it failed to take a critical look at some important operational decisions by Hart and Wilkes that might have given the submarines better opportunities for success against the Japanese onslaught.

Epilogue and Conclusion

Tommy Hart was not present for the demise of his Asiatic Fleet. He was recalled in mid-February, replaced through backdoor maneuvering to Washington by Dutch Vice Admiral Conrad Helfrich.35 Red Doyle departed Fremantle for the U.S. aboard a transport in March 1942, retiring quietly in 1943.36 John Wilkes would go on to achieve flag rank, but he had no further service with the submarine forces during the war. Instead, he was an important factor in preparing the landing forces for the invasion of Normandy. After the war he would serve as Commander, Submarines, U.S. Atlantic Fleet.

The one senior Asiatic fleet submarine leader who continued to contribute to the submarine war against Japan was Jimmy Fife. He commanded all submarine operations out of Brisbane Australia before returning to Fremantle in 1944 to command the submarine forces of the Seventh Fleet for the remainder of the war.

John Wilkes and Jimmy Fife had different personalities and leadership styles, but they complemented each other as they guided the submarines of the Asiatic Fleet through tumultuous events. It is a tribute to the strength of their teamwork that they were able to control so many submarines across such a vast expanse of ocean under adverse and constantly changing circumstances, giving the boats opportunities to be in position to confront the enemy. No less praiseworthy are Wilkes’ raising the red flag about torpedo performance only a month into the war, and Fife’s efforts and dedication to write the insightful report that so accurately captured the lessons of those chaotic months.

These senior officers proved their mettle by exercising solid leadership during a period of retreat and failure. While they certainly could have executed some of their responsibilities to achieve slightly better results, it is unlikely that any changes would have altered the eventual outcome of the campaign.

(Return to December 2022 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

- Ronald H. Spector, Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan (New York:Random House Inc., 1985), 483. Spector quotes war correspondent Hanson Baldwin. ↩

- James Fife, The Reminiscences of James Fife (oral history interviews conducted by John T. Mason). (Oral History Archives at Columbia, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York, 1962), 272. ↩

- Fife, Reminiscences, 214-215. ↩

- Fife, Reminiscences, 188-189, 194-197. See also James Fife, Narrative – Interview recorded 15 February 1944. (Transcript in Clay Blair Collection, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming (hereafter CBC/AHC), Box 67 Folder 5), 2. ↩

- The Asiatic Fleet was the smallest of the three U.S. Navy fleets. It contained no battleships or aircraft carriers, one heavy and two light cruisers, thirteen WW1-era destroyers, the old seaplane tender Langley, and various support and auxiliary vessels. See W. G. Winslow. The Fleet the Gods Forgot: The U.S. Asiatic Fleet in World War II. (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1982). Hart considered the submarines “constituted most of the potentiality of the fleet.” See Thomas C. Hart. War in the Pacific: End of the Asiatic Fleet (Staunton, Virginia: Clarion Publishing, 2013), 39-40. This source was originally a classified Narrative of Events written by Hart after his recall from the Far East in February 1942. ↩

- John E. Wilkes. Narrative – Interview by Captain Wright, recorded 26 April 1945. (hereafter “Wilkes interview,” CBC/AHC, Box 64 Folder 3), 2. See also Clay Blair. Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1975), 131-132. ↩

- Stuart S. Murray. Interview notes by Clay Blair 17 June 1971 (hereafter “Blair’s Murray interview notes,” CBC/AHC, Box 69, Folder 4), sect. 3. ↩

- Fife Reminiscences, 214-215. ↩

- Wilkes interview, 3-4. ↩

- Clay Blair notes, CBC/AHC Box 60 Folder 2. Blair interviewed dozens of submariners who served with Wilkes and Fife, recording their observations on their leadership and character. For Hart’s assessment of Wilkes, see Hart, 50. ↩

- Blair, 145-152. See also John E. Wilkes. War Activities Submarines, U.S. Asiatic Fleet December 1, 1941 – April 1, 1942. (hereafter “Wilkes Report,” National Archives, RG 38), 8-9. ↩

- John D. Alden and Craig R. McDonald. United States and Allied Submarine Successes in the Pacific and Far East During World War II, 4th Ed. (Jefferson North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2009), 27-29. ↩

- Fife Reminiscences, 238. It was Hart who directed Wilkes on Swordfish by message to proceed to Surabaya. When the boats got underway on December 31, they did not know where they were headed – only “south.” See also Blair’s Murray interview notes, sect. 9. ↩

- Wilkes Report, 12. ↩

- Hart, 81-82. ↩

- Theodore Roscoe. U.S. Submarine Operations in World War II. (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1949), 508. The numbers do not include a mission by Trout from COMSUBPAC in February and three other Asiatic Fleet submarines which got underway for special missions planned for April/May but were recalled due to the fall of Bataan or Corregidor. Of the five Asiatic Fleet special missions to Manila in February, two were performed by Swordfish on the same patrol to extricate Quezon and Sayre and their families in successive trips to Manila Bay. ↩

- Fife Reminiscences, 252. ↩

- H. G. Munson, USS S-38. “HMS ELECTRA, Rescue of Survivors,” Confidential memo to Chief of Naval Operations dated March 13, 1942. (Accessed on fold3.com.) ↩

- Hart, 61. ↩

- Blair, 156. ↩

- Wilkes Report, 61-70. Many have mentioned that pre-war training stressed using the sound-only approach from deep, but the reality was that it was used very little, even at the start of the war. When it was, it was invariably unsuccessful. But it is a myth that the submarine force relied primarily on this tactic. The periscope approach was the early skippers’ tactic of choice, until night surface tactics were perfected. ↩

- Barton E. Bacon. USS Pickerel: Report of First War Patrol, December 8-29, 1941. (National Archives, RG 38), 4. ↩

- Blair, 157. ↩

- Fife Reminiscences, 212-213. ↩

- Wilkes Report, 3-4. See also Hart, 50. ↩

- Thomas C. Hart. “Narrative of Events, Asiatic Fleet Leading up to War and from 8 December 1941 to 15 February 1942,” addendum, “Supplementary Narrative” (1946) (National Archives, College Park, MD), 16-17. ↩

- Wilkes interview, 2. ↩

- Wilkes Report, 4. ↩

- Blair, 131. ↩

- Wilkes Report, 9. ↩

- Wilkes Report, 44-45. ↩

- Wilkes Report, 18-19. ↩

- Statement by N.G. Ward, XO USS Seadragon and later CO USS Guardfish. (CBC/AHC, Box 62 Folder 7). ↩

- Fife Reminiscences, 287-291. See also Blair’s Murray interview notes, sect. 23. ↩

- James Leutze. A Different Kind of Victory: A Biography of Admiral Thomas C. Hart. (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1981), 272-282. ↩

- USS Mount Vernon (AP-22) List of Non-Enlisted Passengers dated 6 March 1942. (Accessed at fold3.com (WWII Navy Muster Rolls/M/Mount Vernon (AP-22)/1942/362). ↩