Contents:

Historical Precedent

Scope of the Problem

Yemen: A Case Study

Prescription

A Role for the Navy

Appendix A: Maps

Bibliography

Christian Perkins

55th Annual Naval Academy Foreign Affairs Conference

Domestic Category Prize Winner

Historical Precedent

Since its inception, the United States has made protection of its international interests a priority through transoceanic power projection. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the U.S. projected its military power primarily to maintain its commercial interests. Today, the U.S. continues to use its substantial power projection capabilities to stabilize regions in the name of maintaining global security; it has done so primarily through its substantial navy. 1 Navies have long been essential tools for nations engaging in power projection because they allow an extension of military power across long distances. 2 One of the first operations to this end in which the U.S. Navy engaged sought to protect American trade. Beginning in the late 18th century, pirates from the Barbary States of Africa began to harass U.S. merchant ships. The Confederation Government of the United States found itself unable to raise the funds or naval power to combat these pirates, and resorted to diplomacy to resolve the situation. However, the governments of Tripoli and Algiers refused diplomatic advances and sporadically continued their attacks. By 1801, the U.S. government built up sufficient military force to deploy ships and marines to engage the Barbary States, which they defeated handily. 3 Such military actions taken by the U.S. to protect trade assets set a precedent for using naval power to maintain its interests in remote regions.

The U.S. Navy put forth more extensive efforts to quell instability with the Asiatic fleet in the 1920’s and 1930’s. Internal strife then abounded in China, threatening American lives, trade interests, and property within the region. Well-armed pirates along the Yangtze River often perpetrated this conflict. Due to China’s fragile and preoccupied central government, these pirates controlled territories along the Yangtze River and robbed with impunity. Once the pirates were recognized as a threat, U.S. ships successfully began patrolling the Yangtze River and Chinese ports to maintain order. They drove pirates out of previously lawless regions, and U.S. ships often came to the aid of Chinese cities experiencing civil unrest or instability. The Asiatic fleet carried on the U.S. naval tradition of protecting economic interests and preserving order through show (though not necessarily use) of force. Often, U.S. ships simply had to arrive in an area of instability for conflict to diminish. 4

These examples embody the U.S. Navy’s responses to a myriad of inter- and intra-state conflicts, using its significant power projection capabilities to protect American interests abroad and promote world stability. Displays of U.S. naval power have mitigated the relatively apparent causes of these past conflicts. However, in future decades, increasing freshwater scarcity will complicate intra-state conflicts of interest to U.S. foreign policymakers. Water scarcity has the potential to complicate and exacerbate existing instabilities within states. These heightened conflicts have the potential to destabilize entire regions and topple governments, all from both direct and indirect consequences of water scarcity. Yemen demonstrates a key case study because it is both an example of the effects water scarcity can have on conflict and an area of prime concern to U.S. strategists. If U.S. policymakers remain committed to the goal of world stability, the U.S. Navy will probably involve itself more frequently in conflicts complicated by water scarcity.

The UN defines water scarcity as the point at which the aggregate impact of all users impinges upon the quality or supply of water under prevailing institutional arrangements to the extent that the demand of all sectors, including the environment, cannot be satisfied fully. 5 Policy makers and analysts acknowledge that water scarcity is becoming an international security concern. 6 Water scarcity has already engendered significant instability in the Middle-East, North Africa, and Central Asia. 7 The U.S. State Department has recognized water scarcity as a threat multiplier, meaning that it interacts with other underlying tensions to complicate existing feuds or class struggles. 8 Water scarcity has the potential to exacerbate both inter- and intra-state conflict, although most scholars consider the latter more likely. 9 The National Intelligence Council predicts that this scarcity will only worsen in the next 15 years and must be addressed now to prevent future instability. 10 The countries experiencing water scarcity typically do not have the resources, infrastructure, or proper governance to deal with the problem effectively. 11 It is in the U.S.’s best interest to aid in addressing water scarcity. The National Intelligence Council also argues that the U.S. can increase the likelihood of a future favorable global environment if it remains engaged in the international community and attempts to encourage stability. 12 This paper will first analyze the scope and causes of water scarcity and how it can exacerbate problems within a region. It will next demonstrate the role water scarcity plays in increasing instability by focusing on Yemen as a case study. The paper will conclude with a prescription for actions the U.S. and multilateral institutions should take to address the global problem of water scarcity as well as the possible roles the U.S. navy could play in preserving stability in scarcity stricken regions.

Scope of the Problem

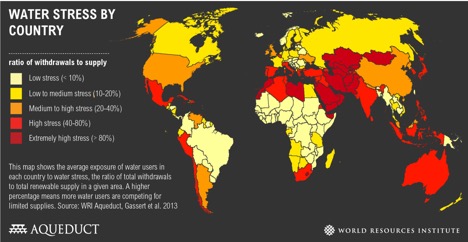

The consensus among analysts is that there is no one cause of water scarcity. 13 Instead, they cite many different trends and problems that interact with each other to cause scarcity. Diverse factors can have differing levels of significance in various regions or countries. 14 Analysts identify the major trends contributing to water scarcity as unprecedented population growth, poorly designed policies, ineffectual government regulation, and increasing climate change. 14 Chronic water mismanagement and pollution interact with these trends as well. 16 Poor governance aggravates these problems so that water scarcity is now pervades in many Middle-Eastern countries like Yemen and Pakistan. 14 Although most of the Middle-East suffers from water scarcity to some degree, it is a global phenomenon. (See Appendix A, Figure 1.) For example, countries as diverse as Somalia, Nigeria, and Uzbekistan, also currently experience water scarcity. Many of these problems are solvable, but have persisted for so long that overcoming them seems impossible. 18 States lacking strong government and resources are the most susceptible to developing serious water scarcity. 14

Scholars have identified inter-state conflict, internal political strife, and ethnic clashes due to migration as categories of conflict that water scarcity worsens. 20 Inter-state conflict occurs most often over water disputes between riparian states. 21 In the past, these inter-state conflicts rarely resulted in extended conflict. 22 Many analysts agree that inter-state conflicts are unlikely since they require a particularistic set of circumstances. The downstream country must be highly dependent on the river’s flow for its national wellbeing, and the upstream nation must threaten to affect the river’s flow substantially. A history of antagonism must exist between the two states and, most importantly, the downstream state must believe it has sufficient military power to rectify the situation. 21 However unlikely, it is important not to discount inter-state conflict completely when discussing water scarcity. Michael T. Klare makes a compelling argument in his book Resource Wars for the potential of future inter-state conflict over water. He posits that if trends of worsening scarcity continue, the likelihood of inter-state water conflict will increase commensurately. 24 Countries have already come close to starting armed conflicts over water disputes. 24 As the resource becomes increasingly scarce, nations could become more aggressive towards the neighbors with whom they share water.

In contrast, analysts predict that intra-state conflicts involving water scarcity are much more likely. 26 Already, many states experience widespread internal instability due in part to water scarcity. 27 Water scarcity is most likely to exacerbate instability in poor or underdeveloped countries that lack the resources to address the issue properly. Parts of California currently suffer extreme water shortages, but the U.S. government possesses the infrastructure and resources to mitigate the drought’s effects. 28 Many countries plagued with water scarcity, however, do not have sufficiently strong governments to address the problem effectively. 29 Countries that do possess the financial resources to address water scarcities are usually dealing with more pressing problems like widespread insurgency or poverty. 30 Water shortages indirectly worsen these seemingly more pressing issues, intensifying instability. 31.

Resource capturing is a common response to water scarcity. Thomas Homer-Dixon defines resource capturing as aggressively acquiring and stockpiling a scarce resource to ensure one’s security. Scarcity encourages empowered groups to obtain as much water as possible to secure their own interests. This leads to the ecological marginalization of less socioeconomically privileged groups. Israel is a prime example of this. In the early 1990s, a water shortage on the West Bank of the Jordan River encouraged financially sound farmers to drill aggressively for more water. These wealthier farmers secured their own economic interests at the expense of other farmers who could not afford to drill for more water. This encouraged many to abandon agriculture and move into cities, hoping to find a better livelihood. Mass migrations have become common in countries plagued with water scarcity and cause a myriad of problems that further contribute to instability. 32

As Israel demonstrates, migrations induced by water scarcity often involve displaced farmers migrating either to an area where water is not scarce or to a city in search of other employment. 33 Sometimes these migrations are transnational. All such scenarios have the potential to cause widespread instability in a country or region. The migration of farmers to regions without scarcity strains populations already settled there. A higher concentration of farmers means more competition for water, land, and business. This can cause strife between migrants and settled populations as well as economic and environmental degradation. 34 A similar effect results when environmental refugees migrate to cities in search of economic and social stability. The overcrowding in cities of nations with widespread water scarcity has raised crime and poverty rates and increased political unrest. 34 Trans-national environmental refugees can strain neighboring countries, potentially heightening regional instability. These migrations have resulted in violent conflict between refugees and native populations of a country and have also damaged relations between states. 34

If a population perceives the government as either exacerbating, or not addressing, water scarcity, political frustration likely will increase. A government unable to mitigate water scarcity cannot address other national problems effectively. Unaddressed water scarcity adds to peoples’ perception that their government cannot maintain security or provide effectively for them. It further complicates problems already causing political frustration in a society. This makes insurgency or revolutionary action more likely. While it will not likely cause an insurgency directly, water scarcity’s indirect effects highlight the shortcomings and mistakes of an ineffective regime and increase a populations’ perceived deprivation. This can promote widespread instability in states struggling with water scarcity. Many of these regimes are vulnerable to, and even existentially threatened by, insurgency. Through its indirect socioeconomic effects, water scarcity increases both the likelihood and the intensity of an uprising. 21

Yemen: A Case Study

Yemen constitutes an example of how water scarcity can increase both internal and regional instability. 30 Yemen has the highest rate of water scarcity in the Middle-East, and analysts project that it will exhaust its water within the next decade. 39 Yemen’s population growth, misguided agricultural policies, significant qat industry, lack of regulation, and high vulnerability to climate change are the key causes of its water crisis. 30 Scarcity has historically been a source of conflict within Yemen. Sana’a University recently conducted a study that found that much of the country’s rising militancy is over resources, including water. 41 Armed insurgencies in North and South Yemen contest for precious water reserves. Militant groups will often use captured water supplies as leverage over both the government and rival groups. 42 Water scarcity intensifies this pervasive security threat and hinders the Yemeni government from addressing the root problem. The water crisis in Yemen has the potential to contribute significantly to its current trajectory toward collapse.

Yemen experienced significant agricultural development beginning in the 1970s. 43 This led to its rapid adoption of advanced farming technologies, steering Yemeni farmers away from traditional water management and agricultural systems. Although these new technologies stimulated the agricultural sector, they also encouraged unsustainable water consumption. The Yemeni government refrained from heavily regulating water usage, fearing it would slow this new growth. It also implemented poorly conceived policies to stimulate agricultural development. Low-interest loans and public investment in surface irrigation kept water extremely cheap, consequently encouraging waste. The failure to regulate water acquisition techniques, such as ground drilling and well sinking, allowed farmers to deplete ground water reserves quickly. This lack of regulation also engendered poorly built wells and pipelines, further increasing waste. 44

Once it realized the country’s water supplies were dwindling, the Yemeni government sought to regulate agriculture and water usage. It promulgated laws prohibiting unauthorized drilling or well digging and limiting water usage for farmers. It also mandated restrictions on the growth of qat, a narcotic plant consumed by most Yemeni people. Qat requires heavy irrigation and accounts for nearly 30 percent of Yemen’s annual water usage. 45 However, most farmers have ignored these new regulations. 46 Agriculture, especially qat cultivation, serves as their sole source of income, and these regulations disrupt their ability to sustain themselves. The central Yemeni government is so weak that it cannot enforce its regulations, and Yemeni farmers have no incentive to follow them, since many of them must cultivate qat to survive. 47

Yemen’s dire security situation prevents it from effectively addressing its water scarcity problem. A Shia group led by Hussein al-Houthi has been waging a war against the national government since 2004. 48 The Yemeni government has not neutralized these rebels, and in January 2015, the group overran the capital city of Sanaa. 49 The Houthi insurgents have taken over regions of Yemen crucial to the country’s water security. Aquifers in the south have become inaccessible because they are completely under insurgent control. Rebel activity has made the region unsafe for government surveyors and hydrologists, further threatening the water security of local populations. These populations think the government cannot solve their water issues, impelling them to support the insurgency. 45

The growing presence and strength of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) has worsened Yemen’s impending implosion. Security analysts consider AQAP to be one of the most powerful and dangerous factions of Al Qaeda. 51 AQAP is currently taking aggressive action against both the Houthi insurgents and the collapsing central government. 52 These actions further disrupt the government and prevent it from reaching a peace agreement with insurgents. 52 The water crisis exacerbates all internal conflicts in Yemen. Before the rise of the Houthi insurgency and AQAP, the Yemeni government enjoyed little popular support partially because of its inability to solve the water crisis. 54 Thus, insurgent movements gained support among the population. The Houthi insurgency has explicitly promised fair and regular utilities to the Yemeni people if it attains power. 52 Unsurprisingly, the region in which the Houthi insurgents are strongest is the northeast, where water scarcity is pervasive.(See Appendix A, Figure 2.)Clearly, water scarcity has worsened instability. The inability of the Yemeni government to provide basic necessities for its people demonstrates its weakness and increases both the likelihood and intensity of insurgency. 52

Yemen is currently the most extreme example of how water scarcity can increase instability in a country and exacerbate other internal issues. It effectively displays how water scarcity can heighten existing political discontent and empower insurgent groups by giving them leverage over the government. The government’s reluctance to regulate water usage due to its fears of hindering economic development may have been a reasonable calculus in the short, but not long, term. In addition, Yemen’s instability has both regional and global ramifications. As the fighting within Yemen has worsened, Saudi Arabia and Iran have turned the struggle between various groups into a proxy war. 57 Iran has begun supplying weapons to Houthi rebels in an attempt to vie for regional influence. 58 The Saudi government has targeted both Houthi rebels and AQAP insurgents in airstrikes while supplying weapons to the Yemeni government. 59 The escalation of a proxy war in Yemen between two of the more powerful countries in the middle-east would have disastrous consequences for the stability of the region. Furthermore, AQAP’s significant presence in Yemen has allowed it to execute terrorist attacks against other countries in the region and against the United States. 52 It would be hyperbolic to claim that water scarcity caused AQAP’s rise to power in Yemen, but it has provided favorable conditions for an insurgent movement to accrue significant influence. 61

Prescription

Yemen is a worst-case scenario of how water scarcity can exacerbate, extend, and complicate existing problems within a country. Analysts agree that Yemen is essentially a failed state and beyond saving. 62 If the Yemeni government had addressed its water problems when first identified, its current situation might not be as dire. Despite the belief that Yemen is a lost cause, the U.S. and UN send significant amounts of money and resources to the state annually. 63 Other water-scarce countries experience many of the same problems to a lesser degree. With timely corrective actions and external aid, these countries can potentially avoid Yemen’s fate. Water scarcity is a multifaceted problem exacerbating diverse sets of problems in different countries. Despite unique factors in each country, most water scarcity cases share a set of common variables.

Although there is no one solution, countries can pursue a set of common solutions that will significantly mitigate water scarcity. Though technical, some of these potential fixes are critical for many countries’ water problems. Addressing water pollution through increased industrial and agricultural regulation is a crucial step many water-scarce countries can take. Rampant industrial pollution has significantly compromised the groundwater reserves of China, Brazil, and Yemen, among others. 64 This is common among developing countries whose industrial sectors are growing rapidly and do not have strong governmental regulations. 65 Another critical step many water-scarce countries can take is to update their irrigation systems. Developing nations with large agricultural sectors, notably those in the Middle-East, waste significant amounts of water through inefficient or dilapidated irrigation systems. 66 For example, analysts estimate that irrigation systems in Yemen waste up to 60 percent of the water they transport due to leakage. 67 Updating irrigation systems would improve water efficiency and raise the government’s legitimacy among its people.

These steps are general; most water-scarce countries can take them to good effect. However, a broader focus on good governance and better regulation should be pursued as well. At present, the aforementioned steps cannot be effectively taken given the current state of many water-scarce governments. The majority of them have a history of poor policy design and implementation, corruption, and non-existent or ineffectual regulation. 31 These factors promote both instability and water scarcity. As with Yemen, weak regimes cannot meet their peoples’ needs, leading to political discontent and social disorder. 61 The U.S. needs to support weak governments through the financing of water scarcity relief projects and the promotion of good governance. Analysts and policymakers have determined the stabilization of the Middle-East to be crucial to U.S. interests, which is why addressing water scarcity in the region should be a priority. 70

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has placed increased attention and funding toward initiatives in the Middle-East aiming to improve governance in the past fifteen years. 71 These initiatives aim to produce long-term improvement in countries with imbedded governance problems such as Egypt, Morocco, and Yemen. 72 USAID has worked on increasing the freedom and efficacy of the press in these countries to increase government responsiveness to their populations. 72 It has also worked with the International Monetary Fund to enhance the skills of government officials in countries with widespread corruption and financial mismanagement. 72 Though these projects are ambitious and well-intentioned, one must remember that the U.S. cannot right every wrong. Policymakers must decide in which countries aid will do the most good and concentrate U.S. resources there.

Water scarcity is such a pervasive global problem that multilateral action must accompany bilateral action by the U.S. In recent years, various international organizations such as the World Bank and the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) have made fighting water scarcity a priority. 75 Although awareness of global water scarcity has risen in the past decade, the U.S. must keep pressing for more international attention devoted to this matter. 76 As noted, the U.S. cannot single handedly ameliorate this pervasive problem. More prominent discussion of water scarcity within the UN would help other leading nations realize that relieving global water scarcity is in their best interest. A 2013 Global Water Institute report predicts that despite increased investment in developing countries’ water security, 2.8 billion people will be dealing with water scarcity in 2025. 77 While financial commitments towards water relief projects from the World Bank have increased steadily over the last fifteen years, to make a meaningful impact on this worsening problem, more international effort and money needs to be allocated toward alleviating global water scarcity. 78 The international community must recognize that access to water is a basic human right. As people are increasingly deprived of this right, instability and conflict will continue to abound. If world leaders want to ensure a stable future global environment, they must make ameliorating this pervasive problem an international priority.

A Role for the Navy

ARABIAN SEA (April 21, 2015) The aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71) and the guided-missile cruiser USS Normandy (CG 60) operate in the Arabian Sea conducting maritime security operations. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Anthony N. Hilkowski/Released)

In late-April 2015, U.S. Navy to this end deployed ships to the Gulf of Aden. 83 Officials stated that the purpose of this operation was to block potential Iranian shipments of arms to the Houthi rebels in Yemen. 84 These actions show that the conflict in Yemen has reached a point of direct concern to U.S. naval strategists. The possibility of a proxy war in Yemen between Saudi Arabia and Iran could have potentially disastrous effects on the regional security of the middle-east. If regional conflict continues to escalate, the U.S. will undoubtedly further utilize its navy in an attempt to preserve stability. The U.S. Navy must acknowledge that it will most likely play a significant role in mitigating conflicts that water scarcity has exacerbated so it can plan accordingly. The multifaceted nature of these water-scarcity affected conflicts requires coherent strategy developed on a case-by-case basis with clearly defined objectives. In each conflict, the naval strategists and U.S. policymakers must determine its priorities and limitations and then decide how involved it will allow itself to become.

Appendix A: Maps

Bibliography

Baechler, Gunther. “Why Environmental Transformation Causes Violence: A Synthesis.” Environmental Change and Security Report. 4 1998. 24-44.

BBC. “Yemen Profile-Timeline.” Last Modified April 1st, 2015. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-14704951.

Bender, Jeremy. “Iran’s Proxy War in Yemen Just Got Exposed.” Business Insider. May 1st, 2015. Accessed June 24th, 2015. http://www.businessinsider.com/irans-proxy-war-in-yemen-just-got-exposed-2015-5.

Biswas, Niloy R. “Is Environment a Security Threat? Environmental Security Beyond Securitization.” International Affairs Review. 20 (2011.)

Black, Richard. “Environmental Refugees: Myth or Reality?.” University of Sussex. (2001.)

Boucek, Christopher. “Yemen: On the Brink.” Carnegie International Endowment for Peace. 110. April 2010.

“Coping with Water Scarcity: An Action Framework for Agriculture and Food Security.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2012.)

Critical Threats Project. “Threats to Yemen.” Last Modified April 3rd, 2015. http://www.criticalthreats.org/yemen.

Custodio, Emilio. “Trends in Groundwater Pollution: Loss of Groundwater Quality and Related Services.” Groundwater Governance: A Global Framework for Country Action. (2011.)

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Coping With Water Scarcity: An Action Framework for Agriculture and Food Security. FAO Water Report No. 38. Rome, Italy. 2012.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. “Impact of Water Scarcity on Food Security for Near East and North Africa Meeting.” Last Modified February 20th 2014. http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/214224/icode/.

Future Directions International. “Crisis in Yemen: Food, Water, and the Slow Coup.” Last Modifies February 25th2015. http://www.futuredirections.org.au/publications/food-and-water-crises/2144-crisis-in-yemen-food-water-and-the-slow-motion-coup.html.

Giesecke, Craig. USAID Knowledge Services Center. “Yemen’s Water Crisis: Review of Background and Potential Solutions.” June 15, 2012.

Glass, Nicole. “The Water Crisis in Yemen: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions.” Global Majority Journal. 1 (2010.)

Griggs, Ray. “Naval Diplomacy and Maritime Power Projection: Proceedings of the Royal Australian Navy Sea Power Conferenc e 2013.” Edited by Andrew Forbes.

Hameeteman, Elizabeth. “Future Water Insecurity: Facts, Figures, and Predictions.” Global Water Institute. (2013.)Homer-Dixon, Thomas and Marc A. Levy, “Environment and Security,” International Security 20 1995.

Holmes, James. “Thinking About the Littoral Combat Ship.” The National Interest. May 22nd, 2013. accessed June20th, 2015. http://nationalinterest.org/commentary/thinking-about-the-littoral-combat-ship-8500.

Homer-Dixon, Thomas. Environmental Scarcity and Global Security. New York: Foreign Policy Association Inc, 1993.

Homer- Dixon, Thomas. Environment, Scarcity, and Violence. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1999.

Huntington P. Samuel. “The Clash of Civilizations?”Foreign Affairs. 5 (1993.)

International Fund for Agricultural Development. Fighting Water Scarcity in Arab Countries. Rome, Italy. 2009.

International Water Policy and Infrastructure Program. “The Water Security Nexus,” By Annabelle Houdret, Annika Kramer, and Alexander Carius. 2010.

Kaplan, Robert D. “The Coming Anarchy.” The Atlantic. Feb 1 1994.

Klare, Michael T. Resource Wars. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2001

Mustafa, Daanish. “Social Construction of Hydropolitics: The Geographical Scales of Water and Security in the Indus Basin.” Geographical Review. 97 (2007.)

Mwangi, Oscar . Journal of Southern African Studies. Vol. 33, No. 1 (Mar., 2007), pp. 3-17

National Intelligence Council. Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds. Washington D.C. 2012.

Naval History and Heritage Command. “Yangtze River Patrol and other US Naval Asiatic Fleet Activities in China, 1920-1942 as Described in the Annual Reports of the Navy Department.” Accessed May 30th, 2015. http://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/y/yangtze-river-patrol-and-other-us-navy-asiatic-fleet-activities-in-china.html.

Reardon, Martin. “Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the Great Game in Yemen” Al Jazeera, March 26th, 2015. Accessed June 24th 2015. http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2014/09/saudi-arabia-iran-great-game-ye-201492984846324440.html.

Renner, Michael. Introduction to the Concepts of Environmental Security and Environmental Conflict. Institute for Environmental Security. 2006.

Renner, Michael. “Environmental and Social Stress Factors, Governance and Small Arms Availability: The Potential Conflict in Urban Areas.” Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. (1998.)

Stratfor Global Intelligence, “Yemen’s Looming Water Crisis,” Last Modified December 1st 2014. https://www.stratfor.com/sample/analysis/yemens-looming-water-crisis.

United Nations. “UN on Water Scarcity.” last modified March 2012 http://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/scarcity.shtml.

United States Institute for Peace. Understanding Pakistan’s Water-Security Nexus. By Daanish Mustafa, Majed Akhter, and Natalie Nasrallah. Washington D.C. Paper No. 88. 2013.

“USAID/DFID/World Bank Governance Roundtable Meeting Summary.” Toward Better Strategies and Results: Collaborative Approaches Towards Strengthening Governance. June-9th-11th, 2011. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Washington D.C.

U.S. Agency for International Development. Democracy and Governance Initiatives in the Middle-East.” Last Modified March 24th, 2014. http://www.usaid.gov/middle-east-regional/democracy-and-governance.

US Agency for International Development. Global Development Alliance Annual Program Statement. Washington D.C. 2015.

US Agency for International Development. “Yemen’s Water Crisis: Review of Background and Potentail Solutions.” By Craig Giesecke. June 5th 2012.

U.S. Department of the State, Office of the Historian. “Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations.” accessed May 30th, 2015. https://history.state.gov/milestones.

U.S. Department of the State, Office of the Historian. “Milestones: Barbary Wars: 1801-1805 and 1815-1816.” accessed May 30th, 2015. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1801-1829/barbary-wars.

U.S. State Department. “Global Water Security: The Intelligence Community Assesment.” last modified May 2012. http://www.state.gov/j/189598.htm.

Vego, Milan. “On Littoral Warfare.” Naval War College Review 68 (2015): 30-68.

Wolf, Aaron T. “Conflict and Cooperation along International Waterways.” Water Policy. 1 (1998.)

Wolf, Aaron T. Kramer, Annika Carius, Alexander, and Geoffrey D. Dabelko. “Navigating Peace.” Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. 1 (2006.)

Work, O. Robert. “The Littoral Combat Ship: How We Got Here, and Why.” January 2013. Newport Paper. U.S. Naval War College. http://awin.aviationweek.com/Portals/AWeek/Ares/work%20white%20paper.PDF.

World Bank. Mapping the Resilience of International River Basins to Future Climate Change-Induced Variability. By Lucia De Stefano, James Duncan, Shlomi Dinar, Kerstin Stahl, Kenneth Strzepek, and Aaron T. Wolf. Water Sector Board Discussion Paper Series. Paper No. 15. March 2010.

World Bank. Water and Climate Change: Understanding the Risks and Making Climate-Smart Investment Decisions. By Vahid Alavian, Halla Maher Qaddumi, Eric Dickson, Sylvia Michele Diez, Alexander V. Danilenko, Rafik Fatehali Hirji, Gabrielle Puz, Carolina Pizarro, Michael Jacobson, Brian Blankespoor. November 2009.

“World Bank Projects.” Last Modified in 2015. http://www.worldbank.org/projects/search?lang=en&searchTerm=&mjsectorcode_exact=WX. :United Nations World Water Assessment Program. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2015. Paris. UNESCO.

(Return to December 2015 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

- “Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations” accessed May 30th, 2015, https://history.state.gov/milestones. ↩

- Vice Admiral Ray Griggs, “Naval Diplomacy and Maritime Power Projection: Proceedings of the Royal Australian Navy Sea Power Conference 2013,” Edited by Andrew Forbes, 1-8. ↩

- “Milestones: Barbary Wars: 1801-1805 and 1815-1816,” accessed May 30th, 2015, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1801-1829/barbary-wars ↩

- “Yangtze River Patrol and other US Naval Asiatic Fleet Activities in China, 1920-1942 as Described in the Annual Reports of the Navy Department,” Accessed May 30th, 2015, http://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/y/yangtze-river-patrol-and-other-us-navy-asiatic-fleet-activities-in-china.html ↩

- “UN on Water Scarcity,” last modified March 2012, http://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/scarcity.shtml. ↩

- Thomas Homer-Dixon, Environmental Scarcity and Global Security (New York: Foreign Policy Association Inc.,1993), 3-12. ↩

- Michael T. Klare, Resource Wars (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2001), 138-190. ↩

- “Global Water Security: The Intelligence Community Assesment,” last modified May 2012, http://www.state.gov/j/189598.htm. ↩

- Thomas homer Dixon, Environment, Scarcity, and Violence (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1999), 133-166. ↩

- National Intelligence Council, Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds (Washington D.C. 2012), 30-36. ↩

- Homer-Dixon, Environment, Scarcity and Violence, 47-52. ↩

- National Intelligence Council, Alternative Worlds, 98-106. ↩

- Aaron T. Wolf, “Conflict and Cooperation along International Waterways,” Water Policy 1 (1998) ↩

- Homer-Dixon, Environment, Scarcity, and Violence, 12-25. ↩

- Homer-Dixon, Environment, Scarcity, and Violence, 12-25. ↩

- Michael Renner, Introduction to the Concepts of Environmental Security and Environmental Conflict, Institute for Environmental Security, (2006): 1-5. ↩

- Homer-Dixon, Environment, Scarcity, and Violence, 12-25. ↩

- Aaron T. Wolf, Annika Kramer, Alexander Carius, and Geoffrey D. Dabelko, “Navigating Peace,” Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 1 (2006): 1-3. ↩

- Homer-Dixon, Environment, Scarcity, and Violence, 12-25. ↩

- Niloy R. Biswas, “Is Environment a Security Threat? Environmental Security Beyond Securitization,” International Affairs Review 20 (2011): 5-10. ↩

- Homer-Dixon, Environment, Scarcity, and Violence, 133-166. ↩

- Wolf, “Conflict and Cooperation” ↩

- Homer-Dixon, Environment, Scarcity, and Violence, 133-166. ↩

- Klare, Resource Wars, 138-190. ↩

- Klare, Resource Wars, 138-190. ↩

- For a detailed explanation see the following sources: Daanish Mustafa, “Social Construction of Hydropolitics: The Geographical Scales of Water and Security in the Indus Basin,” Geographical Review 97 (2007): 484-501, Thomas Homer-Dixon, Environmental Scarcity and Global Security (New York: Foreign Policy Association Inc.,1993), Michael T. Klare, Resource Wars (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2001. ↩

- Michael Renner, “Environmental and Social Stress Factors, Governance and Small Arms Availability: The Potential Conflict in Urban Areas,” Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars (1998): 2-5. ↩

- Homer-Dixon, Environment, Scarcity, and Violence, 47-72. ↩

- Nicole Glass, “The Water Crisis in Yemen: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions,” Global Majority Journal, 1 (2010): 17-20. ↩

- Glass, “Water Crisis in Yemen,” 17-20. ↩

- Homer-Dixon, Environment, Scarcity, and Violence, 73-106. ↩

- Homer-Dixon, Environment, Scarcity, and Violence, 136-166. ↩

- Richard Black, “Environmental Refugees: Myth or Reality?” University of Sussex, (2001): 1-3. ↩

- Renner, “Environmental and Social Stress Factors,” 8-15. ↩

- Renner, “Environmental and Social Stress Factors,” 8-15. ↩

- Renner, “Environmental and Social Stress Factors,” 8-15. ↩

- Homer-Dixon, Environment, Scarcity, and Violence, 133-166. ↩

- Glass, “Water Crisis in Yemen,” 17-20. ↩

- Stratfor Global Intelligence, “Yemen’s Looming Water Crisis,” December 1, 2014, 1-2. ↩

- Glass, “Water Crisis in Yemen,” 17-20. ↩

- Giesecke, Craig, USAID Knowledge Services Center, “Yemen’s Water Crisis: Review of Background and Potential Solutions,” June 15, 2012. ↩

- Stratfor, “Yemen’s Looming Water Crisis,” 1-4. ↩

- Glass, “Water Crisis in Yemen,” 20. ↩

- Glass, Water Crisis in Yemen,” 20-22. ↩

- Stratfor, “Yemen’s Looming Water Crisis,” 3-6. ↩

- Glass, “Water Crisis in Yemen,” 22. ↩

- Glass, “Water Crisis in Yemen,” 20-22. ↩

- “Yemen Profile,” last updated February 27th, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-14704951. ↩

- “Yemen Profile,” http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-14704951. ↩

- Stratfor, “Yemen’s Looming Water Crisis,” 3-6. ↩

- “Threats to Yemen,” Accessed 3/10/2015, http://www.criticalthreats.org/yemen ↩

- “Threats to Yemen,” http://www.criticalthreats.org/yemen. ↩

- “Threats to Yemen,” http://www.criticalthreats.org/yemen. ↩

- “Crisis in Yemen: Food, Water and the Slow Motion Coup,” accessed 3/18/2015, http://www.futuredirections.org.au/publications/food-and-water-crises/2144-crisis-in-yemen-food-water-and-the-slow-motion-coup.html. ↩

- “Threats to Yemen,” http://www.criticalthreats.org/yemen. ↩

- “Threats to Yemen,” http://www.criticalthreats.org/yemen. ↩

- Martin Reardon, “Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the Great Game in Yemen,” March 26th, 2015, Al Jazeera, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2014/09/saudi-arabia-iran-great-game-ye-201492984846324440.html. ↩

- Jeremy Bender, “Iran’s Proxy War in Yemen Just Got Exposed,” May 1st, 2015, Business Insider, http://www.businessinsider.com/irans-proxy-war-in-yemen-just-got-exposed-2015-5. ↩

- Bender, “Iran’s Proxy War,” http://www.businessinsider.com/irans-proxy-war-in-yemen-just-got-exposed-2015-5. ↩

- “Threats to Yemen,” http://www.criticalthreats.org/yemen. ↩

- Homer-Dixon, Environment, Scarcity, and Violence, 142-147. ↩

- Stratfor, “Yemen’s Looming Water Crisis,” 4-5. ↩

- “Democracy and Governance Initiatives in the Middle-East,” last updated March 24th, 2014, http://www.usaid.gov/middle-east-regional/democracy-and-governance.: ↩

- Emilio Custodio, “Trends in Groundwater Pollution: Loss of Groundwater Quality and Related Services,” Groundwater Governance: A Global Framework for Country Action, 2011. ↩

- Homer-Dixon, Environment, Scarcity, and Violence, 49-51. ↩

- “Coping with Water Scarcity: An Action Framework for Agriculture and Food Security,” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, (2012): 13-14. ↩

- Glass, “Water Crisis in Yemen,” 27. ↩

- Homer-Dixon, Environment, Scarcity, and Violence, 73-106. ↩

- Homer-Dixon, Environment, Scarcity, and Violence, 142-147. ↩

- National Intelligence Council, Alternative Worlds, 98-106: “Near Eastern Affairs: Regional Topics,” last updated, 2015, http://www.state.gov/p/nea/rt/index.htm. ↩

- “USAID/DFID/World Bank Governance Roundtable Meeting Summary,” Toward Better Strategies and Results: Collaborative Approaches Towards Strengthening Governance, June-9th-11th, 2011, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington D.C. ↩

- “Democracy and Governance Initiatives in the Middle-East,” http://www.usaid.gov/middle-east-regional/democracy-and-governance. ↩

- “Democracy and Governance Initiatives in the Middle-East,” http://www.usaid.gov/middle-east-regional/democracy-and-governance. ↩

- “Democracy and Governance Initiatives in the Middle-East,” http://www.usaid.gov/middle-east-regional/democracy-and-governance. ↩

- “Findings of the World Bank’s Independent Evaluation Group,” last updated 2011, http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/EXTOED/EXTWATER/0,,contentMDK:22508543~menuPK:6817435~pagePK:64829573~piPK:64829550~theSitePK:6817404,00.html: “Coping with Water Scarcity: An Action Framework for Agriculture and Food Security,” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, (2012): 1-3. ↩

- Elizabeth Hameeteman, “Future Water Insecurity: Facts, Figures, and Predictions,” Global Water Institute, (2013): 3. ↩

- Hameeteman, “Future Water Insecurity: Facts, Figures, and Predictions,” 3-5. ↩

- “World Bank Projects,” last updated in 2015, http://www.worldbank.org/projects/search?lang=en&searchTerm=&mjsectorcode_exact=WX.:United Nations World Water Assessment Program, The United Nations World Water Development Report 2015, Paris, UNESCO. ↩

- James Holmes, “Thinking About the Littoral Combat Ship,” The National Interest, May 22nd, 2013, accessed June20th, 2015, http://nationalinterest.org/commentary/thinking-about-the-littoral-combat-ship-8500. ↩

- Robert O. Work, “The Littoral Combat Ship: How We Got Here, and Why,” January 2013, Newport Paper, U.S. Naval War College. http://awin.aviationweek.com/Portals/AWeek/Ares/work%20white%20paper.PDF. 2-7. ↩

- Milan Vego, “On Littoral Warfare,” Naval War College Review 68 (2015): 31-41. ↩

- Work, “The Littoral Combat Ship,” 2-7. ↩

- Jim Sciutto and Jamie Crawford, “U.S. Warships near Yemen Create Options for Dealing with Iranian Vessels,” CNN, April 22nd, 2015, http://www.cnn.com/2015/04/20/politics/iran-united-states-warships-monitoring/. ↩

- Sciutto and Crawford, “U.S. Warships near Yemen,” http://www.cnn.com/2015/04/20/politics/iran-united-states-warships-monitoring/. ↩

Pingback: Water Scarcity, Conflict, and the U.S.Navy - News4Security

Pingback: Water Scarcity, Conflict, and the U.S.Navy | Norfolk Security