Contents:

The State of the Navy

Encouraging Enlistment

Naval Militias

Conclusion

Daniel Roberts

Naval History and Heritage Command

In April of 1898, the former Spanish Minister of Marine José María Beránger y Ruiz de Apodaca was confident that the Spanish Navy would be victorious combat with the United States. He informed the newspaper El Imparcial:

I have already said that we shall conquer on the sea, and I am going to give you my reasons. First of these is the remarkable discipline that prevails on our war ships, and the second, as soon as fire is opened, the crews of the American ships will commence to desert, since we all know that among them there are people of all nationalities. 1

A similar boast appeared in the Manila daily papers in late April. Spanish Governor General, Basilio Agustin y Dávila, declared certain Spanish victory. Augustin claimed Commodore George Dewey and his “squadron manned by foreigners,” would be defeated, as they were pirates, intent only on taking “possession of [Filipino] riches as if they were unacquainted with the rights of property.” 2

The derisory observations of Beránger and Augustin did little to lift the spirits of defeatist Spanish naval officers, 3 but they were not without veracity. Even American naval officers worried that their vessels were crewed by a peculiar mixture of foreigners, pirates, and undisciplined amateurs.

Historiography of the United States Navy in the Spanish-American War (1898) focuses almost exclusively on the Naval Academy-educated officer class. Social histories of enlisted soldiers in the Spanish-American War are prevalent, but enlisted sailors have been neglected and, so too an important aspect of the United States Navy’s evolution between the Civil War and World War I. 4 The exclusion of enlisted history is particularly surprising given that the United States Navy resorted to controversial methods to meet an emergency need for sailors. These methods included enlisting foreign sailors, naval militiamen and employing civilian merchantmen as mercenaries. Enlistment from these groups was done in defiance of the desires of congress, career naval officers, and the laws of the United States. Each of the three groups presented distinct challenges, but, in each case, the vast majority of the men distinguished themselves with diligence, intelligence, and courage. Shortly before World War I, the Navy modernized their enlisted recruitment and formed a Naval Reserve, but, for six months in 1898, the fate of the United States lay in the hands of foreigners, mercenaries, and amateurs.

The State of the Navy

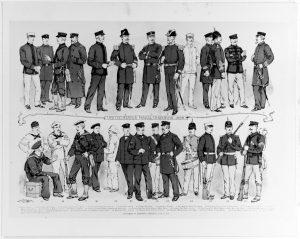

Before and during the war with Spain, the United States Navy suffered from a severe shortage of qualified sailors. As tensions increased the Navy Department became desperate for men to serve on understaffed naval vessels, and, to crew more than two dozen additional vessels commissioned between January and August of 1898. 5 Congress voted to expand the permissible enlisted strength of the Navy from 10,000 men to 20,000 men, 6 but finding suitable men proved difficult. Each vessel was a complicated and, as the battleship Maine demonstrated on February 15, 1898, volatile machine requiring education and experience to operate beyond the traditional understanding of “seamanship.” 7

Supplement to Harper’s Weekly, June 25, 1898. Artist: H.A. Ogden. The illustration depicts and labels various forms of Naval and Marine Corps uniforms. (NHHC Photo # NH 86170-KN)

Life aboard naval vessels was grueling, lonely, dangerous and came with few long-term benefits. Repeated attempts before the war to improve enlistment and retention of American seaman largely failed and were made worse by high rates of desertions. Navy-wide, desertion rates consistently remained higher than 10% annually during the 1890s. In 1892 alone, 1,260 enlisted men out of a total force of 8,250 deserted, around 15%. The Navy started an apprentice program to train teenage boys on naval vessels, but it attracted few candidates, and those it did attract deserted in similar numbers. 8

While the United States Army offered a pension after 30 years of service, the Navy provided no retirement, and, even if it had, the prospect offered little comfort. The editor of Our Navy, Lodwyck Hornebeek, wrote that nearly one half of all enlisted men were employed in firerooms, where, “after a man has served twenty-five years… he will be a candidate for a disability pension, if not for funereal honors.” 9

The Navy also competed for American seamen with merchant shipping interests, where skilled American sailors received higher pay and regular career advancement. Enlisted sailors in the Navy had almost no chance of advancement past a warrant rank. Receiving a commission was nearly impossible without attending the United States Naval Academy, an unattainable goal for enlisted sailors. 10 This ceiling on advancement was demoralizing. Boatswain Henry Hudson summed up the feelings of enlisted men when he testified to the Naval Affairs Sub-Committee in 1894, that: “It does not satisfy the ambition of an American citizen of the United States to stand still.” 11

One area where the Navy was successful was enlisting from the international community of merchant sailors. In 1897, the year before the Spanish-American War, the Bureau of Navigation reported that 74% of its personnel were American citizens. The other 26% of enlisted men in the U. S. Navy were citizens of foreign countries. However, 46%, nearly half, of the enlisted men in the United States Navy were foreign born. 12 These high percentages were the result of expediency. Commanding Officers were entrusted with enlistment and they found skilled foreign sailors in urban port cities where international merchantmen made berth. Some American officers even preferred foreign sailors because they tended to re-enlist and deserted in fewer numbers. 13

This longstanding and highly successful source of sailors was challenged in the 1890s by racist and nativist attitudes in both the Navy and Congress. In a United States Naval Institute prize winning essay, Ensign Albert P. Niblack gave voice to officers’ concerns when he railed against the employment of foreign sailors, stating:

… it is the height of folly for a rich and powerful nation to rely on mercenaries and hirelings in the exigencies of war…neglecting in time of peace to train up a picked body of her own citizens to bear arms for national defense. 14

According to Captain Francis J. Higginson, the Navy wanted, “boys who have never seen, and do not know, any other flag than the American, who have good American backgrounds, and who have no old world allegiances.” 15

Congressmen Adolph Meyer of Louisiana asked Gunner Frank C. Messenger about foreign sailors in the Navy during an 1894 Naval Affairs hearing. Messenger recounted that of a 270 man crew on the Atlanta, only 60 were native-born Americans; the rest were foreigners from “Norway, Sweden, Germany,” and the British Isles. According to Messenger, foreign sailors indicated no desire for naturalization and had no sympathy for the United States. They enlisted only for the money. Congressmen Meyer asked Messenger, “Have you ever seen them under conditions which would test the courage and patriotism of a man on board ship?” Messenger responded: “No, sir; but I should keep my eye on them, if ever we were in action. I think it would be advisable, especially if we were in action with their country.” 16

The war with Spain brought trepidations about foreign sailors to the forefront. The Spanish were familiar with the American practice of foreign enlistment and saw it as one of the U. S. Navy’s chief weaknesses. Whether the Spanish thought to capitalize by placing spies and saboteurs in the American Navy is unknown, but there were rumors. Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, Commodore Arent S. Crowninshield, forwarded a report from the U. S. Secret Service to Commodore George C. Remey at the Key West Naval Base on May 31st. According to the Secret Service, two Spanish saboteurs, Ramon Maldonado and Don Miguel Lopez, planned to enlist as Assistant Engineers. Both were fluent in English and very “capable of passing themselves off as American.” Maldonado had a “light complexion; very dark Spanish eyes,” and was missing his little finger on the left hand above the second joint. Lopez had a “dark complexion;” and a “small head.” His initials were tattooed on his left wrist and a ship and serpent on his right forearm. 17 Whether these two men actually existed is not known, but fear that they might, and that there might be others like them, was very real. 18

Commodore Winfield S. Schley, commander of the Flying Squadron, transferred the Chief Master at Arms on the armored cruiser Brooklyn, Joseph Cuenca, to the revenue cutter Franklin weeks before the war. Schley explained to Crowninshield:

This transfer, which seemed to me imperative, was ordered owing to the fact that I received information that Cuenca was a Spaniard and, though naturalized, I did not feel that his retention at such a time was desirable. 19

Cuenca was, and remained, a loyal American. He served during the Spanish-American War and Philippine Insurrection, and is mentioned in the July to December 1900, log book of the Concord after receiving a medal for good conduct. 20 His transfer was symptomatic of the paranoia concerning foreign sailors.

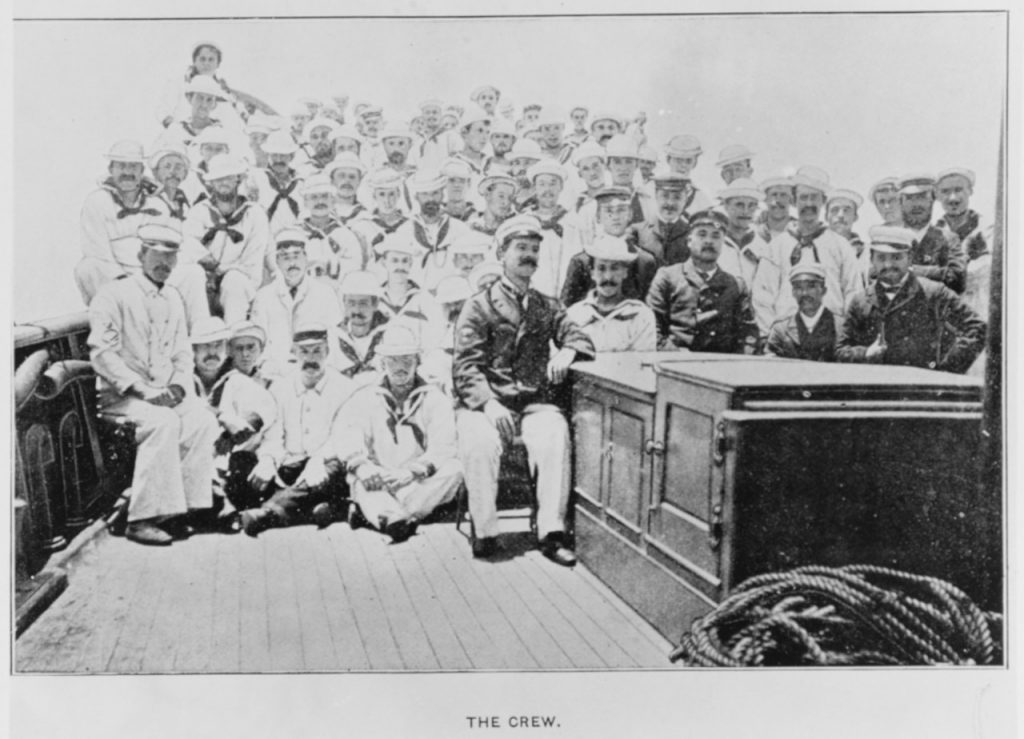

Encouraging Enlistment

Frederick S. Harrod’s, Manning the New Navy: The Development of a Modern Naval Enlisted Force, 1899-1940 21 describes the concerted effort made by the Navy after the Spanish-American War to encourage the enlistment of more American sailors, particularly those from the heartland, but during the war foreign enlistment continued out of expediency. In no theater was this more apparent than on the Asiatic Station where Commodore George Dewey enlisted a substantial number of Chinese sailors directly counter to the wishes of the Navy Department. Citizenship and entry into the United States was denied to ethnic Chinese immigrants by the 1882 Chinese Exclusionary Act and their service upon naval vessels was highly discouraged. Dewey, and the other commanders on the Asiatic Station before him, ignored these objections. Chinese sailors served as mess attendants, stewards, coal passers, and firemen. Of Dewey’s squadron at the Battle of Manila Bay, 1 of every 20 men was ethnic Chinese, and 29 served on Dewey’s flag ship, Olympia. 22 One of them, Dewey’s steward, served under both of the previous Asiatic Station commanders. 23 After the war Dewey made a very public case that 50 of his Chinese sailors should be honored with U.S. citizenship. His hopes were unceremoniously dashed when Congress refused to take up the issue. The sole American citizen of Chinese descent with Dewey, Steward Ah Soong, was humiliated when he had to petition Secretary of the Navy John D. Long to land in San Francisco after losing his passport. 24 Whether the Navy Department appreciated them or not, foreign sailors played a substantial role in manning the United States Navy during the Spanish-American War. 25

Other ships added to the Navy’s force came equipped with their own crews. 26 Merchant steamers of the American Line were drafted into service shortly before the war by order of President William McKinley. American Line vessels received government subsidies under the Postal Aid Act of 1891. In exchange for a subsidy and the right to carry mail, the United States Navy reserved the right to employ American Line vessels as auxiliary cruisers. On April 15, 1898, the S.S. St. Paul, St. Louis, New York and Paris were commissioned and armed by the Navy. New York and Paris were renamed Harvard and Yale, and a small coterie of Naval officers, marines, and naval guns were placed aboard all four ships. The civilian crews of each vessel signed on as contractors, while the captains of the vessels were commissioned as navigation officers. 27

Using skilled contract sailors was expedient, but created mortal complications. Uniformed sailors were protected by the 1864 Geneva Convention, but American Line sailors risked accusations of piracy. This fact weighed heavily on Captain Charles S. Cotton when Admiral Pascual Cervera’s squadron blockaded Harvard at St. Pierre, Martinique. Cotton wrote Long:

In view of all the encumbrances connected with my situation here; of the presence of a powerful Spanish fleet, including fast destroyers, in our vicinity; of their undoubted intention to capture this ship if possible; of her great value to the U.S.; of her much greater value, sea prize, to Spain; of the fact that it requires nearly one hour after getting underway for this ship to reach a speed of 20 knots; of the peculiar status of the officers and crew, who are serving on board of an armed ship while they do not belong to either branch of the Naval or Military service of the U.S.; the doubt as to their treatment by Spain, under the existing conditions would they be captured, — a long and careful consideration of all those conditions finally led me to the conclusion; that I would be fully justified in not putting to sea at the present time; and I acted accordingly… 28

Cotton decided he would pretend his boilers needed servicing if the French colonial governor ordered him out rather than risk engagement. Fortunately for Cotton and his crew, Cervera, short on coal, ignored Harvard and steamed for Curaçao. 29

If there were any concern that “irregular sailors” lacked discipline, skill, or courage, said concern was laid to rest by their distinguished service in the war. Of note were the crews of the St. Louis and St. Paul. Both vessels were involved in multiple actions with the enemy. St. Louis, commanded by Captain Caspar F. Goodrich – himself a longtime champion of irregular forces in naval service 30 – successfully cut three underwater telegraph cables with a ship wholly inappropriate for the task. While cutting the cable at Santiago de Cuba, his crew was under constant fire for 40 minutes. Goodrich wrote to Rear Admiral William T. Sampson:

You are doubtless aware of the peculiar conditions under which the officers and crew of this vessel are now serving their country. The Officers are not appointed in the Navy, nor are the men enlisted, yet greater bravery in action or more devotion to their flag than theirs could not have been shown. With shells whistling over their heads, the gang of men, who under Chief Officer Seagrave, were employed on the forecastle in the dangerous task of heaving up the telegraph cable, never flinched but stuck to their posts to the end. 31

St. Paul also distinguished itself under command of Captain Charles D. Sigsbee. Sigsbee’s crew singlehandedly blockaded Cervera’s squadron at Santiago de Cuba, irreparably damaged the torpedo-destroyer Terror in an engagement at San Juan, and extricated wounded Americans and Spanish prisoners of war from Siboney. 32 The use of civilian sailors was considered by Goodrich, Sigsbee and their fellow Naval Officers to be an undisputable success. 33

Probably the most controversial group from which the Navy drew emergency personnel during the Spanish-American War, were members of the Naval Militia of the individual states. In total, 4,224 militiamen enlisted and another 267 were commissioned as officers. The militia accounted for one out of every six sailors in service during the war and the vast majority of wartime naval enlistees. 34

The Navy’s attempts to implement a national naval reserve after the Civil War never materialized, mostly due to congressional inaction. There was hope that a sense of patriotic duty would provoke a mass enlistment of American merchant seaman in time of war, but this hope was misplaced. The American merchant marine declined after the Civil War and could not realistically sustain the Navy’s needs, although they were willing as shown by the experience of sailors from the American Line. 35 Instead, the reserve function fell to the enthusiastic amateurs of state naval militias.

The first naval militia was founded by the Massachusetts legislature in 1888 as a coastal defense battalion of the state’s National Guard. By 1898, seventeen other states founded militia battalions along similar lines. 36 Each battalion was organized, sponsored, and commanded, by former Naval Academy graduates and retired Navy officers eager to maintain a relationship with the service. The Navy Department hoped the militias would enlist men from seafaring trades, but instead most of the battalions quickly filled up with “landed” professionals: attorneys, bank clerks, doctors, etc. Naval militias became gentlemen’s clubs for middle and upper class professionals wishing to spend their leisure hours doing patriotic duty. These highly educated, wealthy, powerful, and civically-engaged men had little experience with life at sea, but they used their influence to aid the expansion and funding of their organizations in state legislatures.37

Naval Militias

The Navy Department was discouraged and uncertain about what do with the naval militias. Assistant Secretary of the Navy William McAdoo wrote in 1895 that militias were, “local or State organizations of citizens of aquatic tastes rather than those of the strictly seafaring class.” 38 Questions arose about exactly what role the naval militias might serve in war. Did they constitute local defense or could they be brought together to function as a national organization? Would they serve as a naval reserve or did they owe their service to the governor of their state? No one in the Navy Department, or the naval militias, had clear answers to these questions. 39 As a result, the Navy was hesitant to commit resources to an entity with no clear strategic purpose.

Naval Militia organizations received only $25,000 per annum from Washington. While this stipend was doubled to $50,000 in 1897, the amount did not even cover the cost of training literature, which had to be paid for by donations from generous militia members and subsidies from state legislatures. 40 Regardless of the Navy’s neglect, the number of men in the militia expanded from little more than 1,000 men in 1891 to 4,157 in 1897. Militia Capt. John W. Miller referred to the existence of the naval militias as a, “triumph of persevering intelligent citizens over almost insuperable difficulties…” 41Training of militia members was inconsistent. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt wrote, “the widest difference obtains between the different organizations.” Some militia accumulated years of intermittent training and demonstrated basic competency. Others did not. According to Roosevelt, at least one organization, “in the Southern States[,]… made its appearance aboard ship with the officers rowing the men, as they were the only ones who knew how to row.” 42

As tensions with Spain increased, so too did debate over how naval militiamen might be used. Naval officers, including the Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, Commander Francis W. Dickens, publicly criticized the militia and scoffed at their being used on regular Naval vessels. 43 Dickens and his fellow officer argued that warships and naval tactics were far too complicated and dangerous for amateur seafarers. Captain A. P. Cooke wrote:

A promiscuous collection of landsmen and untrained seafaring men, hastily placed aboard such vessels would be rather more dangerous than useful . . . . It is not easy to realize how completely all the conditions of war have changed within the last generation of men. 44

Officers complained militiamen endowed with “too much brains,” and that a ship crewed with them “would do more thinking than fighting.” Underlying their concern was the idea that educated men were ill-suited for the strict discipline and grueling work on a naval vessel. Because of inconsistency in training and supervision, regular naval officer rejected the ranks and designations of state militia and insisted that no militiamen be enlisted at a rating higher than “landsmen.” 43

Within the Navy Department there was one important militia proponent. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt followed the Naval Militia closely and supported the movement. He wrote to Secretary Long suggesting that the oldest state militias were qualified to, and should, constitute the crews of auxiliary cruisers. He specified that the: New York, Massachusetts, Michigan, Maryland and New Jersey militias were “efficient” enough for the task and wrote:

All of this emphasizes the wisdom of the Department of in enlisting the Naval Militia individually, and in preventing the recognition by the Department of all the different Naval Militia organizations as being on the same plane. It is the purpose of the Department to keep the Naval Militia together in their battalion and division organizations, and it will be very unwise to act otherwise… The five chosen to man the deep-sea patrol vessels are those for which we have the best reports from the regular officers during the past year. They are all five thoroughly efficient organizations. 42

Roosevelt wanted to give the most experienced militias a chance to fight as a unit, which should come as no surprise given his own plans to raise a volunteer cavalry regiment. The five state militias Roosevelt named received their own ships, while the Bureau of Navigation required militiamen from the “less efficient” state organizations to enlist as able-bodied seaman and landsmen. 47

On May 4th, Congress gave Secretary Long $8,830,000 to cover the expenses and pay of militiamen who joined the new Auxiliary Naval Force, ordered into existence for the duration of the war. President McKinley used his authority to commission warrant and line officers from militias and requested that state governors relinquish authority over militiamen so they might join the regular navy. McKinley received unanimous consent. 48

Naval militiamen were utilized in multiples ways. The most advanced battalions were kept together, given regular Navy commanders, executive, and warrant officers, and placed on sea-going vessels as complete units. Naval militia from other states were employed piecemeal and assigned to the Auxiliary Naval Forces on the Pacific and Atlantic coast. These militiamen served on lighthouse tenders, revenue cutters, tug boats, and recommissioned Civil-War-era monitors. A select group were assigned to the Coastal Signal Service, a series of coastal semaphore stations that stretched from Maine to Texas. 49 The final group, which constituted a majority of militiamen, (around 2,600), enlisted in the regular Navy as landsmen and boarded vessels at Key West, New York, and Hampton Roads as reinforcements. 50

Performance by the naval militia on the sea varied. Their success or failure generally resulted from previous training, the leadership of their officers, and the command organization on the ship. Militiamen were all universally unfamiliar with the details and disciplines of Navy life. The 1st Battalion of the New York Naval Militia, which served on U.S.S. Yankee, was arguably the best trained of all the state organizations, but even that amount was inadequate to prepare them for life at sea. Captain Willard H. Brownson of Yankee remarked to Secretary Long that, “any success attended this experiment was in spite of – and not the result of – their previous training.” 51

Men were repeatedly cited for not cleaning the ship properly, putting equipment in the wrong place, and having soiled uniforms. 52 Brownson claimed the problem was a lack of experienced petty officers:

Their deficiencies were entirely the result of want of experience. In caring for their messes, their bags and hammocks, scrubbing their clothes, and in many of the minor details of a man of war, they were almost entirely ignorant; but this would have disappeared at an early day had there been among them a sprinkling of man of war’s men whose examples they could have followed. 51

In the New York Militia, petty officers were elected during the pre-war “social club” era, and not out of any regard for their qualifications. Brownson wrote to Secretary John D. Long:

It is unreasonable to think that a class of people, whatever may be their interest in, and natural aptitude for, things pertaining to the sea, whose occupations are entirely those of landsmen, can by a few days training yearly on a man of war, and considerable time spent in drills on board of a hulk, be fitted to perform the duties of a watch officer at sea. The necessary experience for Division Officers they can, and do, get; but the sea habit; and the knowledge of the sea necessary to take charge of a deck under ordinary conditions, can only be acquired at sea, and this experience they did not have. 51

Regular Navy officers were also concerned with the familiarity between petty officers and the crew. Sailors tended to ignore the more onerous, at times erroneous, instructions from their former peers and demonstrated a distinct lack of military decorum. First Lieutenant John Hubbard of Yankee recounted an instance when a sailor yelled “Good Morning Billy,” to the officer on watch and received a “Good Morning Reggie,” in return. 55

On most of the militia vessels problems ended with minor infractions of Navy etiquette, but some militiamen proved grossly unfit or willfully insubordinate. Lt. Lazarus L. Reamey was ordered to command a crew of New Jersey Naval Militia and deliver the Civil War monitor Montauk to the “Portland Naval Reserve,” in Maine. Reamey early on discovered that the engineer force of the New Jersey Militia were not up to the task. He wrote:

The present engine room force, except officers, is not sufficiently reliable to make it safe to move the ship without the assistance of a tug, which fact was fully demonstrated upon the passage from League Island here – The work was so poorly done that the engines (for lack of steam) stopped several times. 56

His apprehension increased when he met the “commander” of the Portland Naval Reserves, William Henry Clifford, Jr. Maine had no organized militia, and Clifford’s force consisted of, “for officers… a few young men (lawyers, railroad or bank clerks and newspaper reporters) who, [served] under the leadership of Mr. Clifford (a very young man)…” 56 Clifford “did not feel qualified,” to select any petty officers. Instead he requested Reamey leave men from the New Jersey Militia willing to stay. Reamey wrote to Commodore Crowninshield:

Judging from the information at hand, I fear that the prospect for finding men who can be safely entrusted to properly care for the engines and boilers, even in port, is very poor… While anxious to fully comply with my instructions I feel it my duty, before the Changes are made, to submit the above information for the Department’s consideration. 56

It is difficult to argue with Reamey’s findings.

Yosemite, under Commander William H. Emory, and crewed by the Michigan Naval Militia, was able to get up to steam, but faced repeated problems associated with severe breakdowns in discipline. From the outset, one militiaman complained to his congressmen about officer assignments. This invited a severe rebuke from Secretary Long to both the man and Commander Emory. 59 In June, Yosemite was sent to Jamaica to capture the Purisima Concepcion, but completely missed the Spanish steamer when it passed them at 5 a.m. on June 16. Word of the failure incited public scandal. Crewmen, Michigan newspapers, and Emory, claimed the officer of the watch, Lt. Gilbert Wilkes, was drunk. 60 Wilkes, in turn, was defended by Chief Boatswain’s Mate Henry B. Joy, who claimed that Emory repeatedly ignored Wilkes summons when he spotted Purisima Concepcion. 61 The matter was a public blemish on the Michigan Naval Militia’s service. Then, in July, Emory remanded 28 men to the brig after a good portion of the crew was drunk and absent without leave during a stop in St. Thomas. The men were returned by local police for a bounty of $10 a head. One inebriated Coal Passer named Ruscoe assaulted Yosemite’s Master at Arms. 62 Ironically, Michigan’s was the only militia crewed primarily by men who worked in commercial shipping. 63

Montauk and Yosemite were exceptions. Most militiamen accepted the discipline and their enthusiasm was greatly admired by their regular navy officers. Commander Charles J. Train, who commanded a crew of Massachusetts Naval Militia on Prairie, sang his crews praises. Train wrote to Long:

These men belonged to the Mass. Naval Militia, an organization which had nothing Naval about it, save the name; which was not formed for the purpose of providing crews for sea-going Men-of-War, and whose members possessed none of the qualifications for Seamen in the Navy of the United States, other than the patriotism, zeal and intelligence belonging to all New England boys. 64

Train further wrote he was particularly impressed by the men’s patience and industry, even though the Prairie’s wartime cruise, “furnished no chance of an occasional attack of an enemy to break the monotony and furnish the excitement which alone can make such a life endurable.” 64 Even the pessimist Brownson spoke glowingly of his crew’s, “zeal and intelligence, and the interest they exhibited in their work generally, and especially in all that related to the [gun] battery and to preparation for battle.” 51 Militiamen must have been doing something right, because of the ships selected for the Eastern Squadron poised to attack Spain and reinforce Dewey in the Philippines, four: Yankee, Yosemite, Badger and Dixie, were crewed almost entirely by militia. 67

The militia seemed to function best when serving under experienced petty officers and understanding and flexible commanders. After all, many militiamen were skilled engineers, doctors, intellectuals, and businessmen in civilian life. Rear Admiral John Hubbard, former executive officer of the Yankee, remembered:

…that it was a pity to be wasting, as it seemed to him, so much fine material in positions that to his mind could have been quite as well, if not better, served by individuals of more developed brawn and less cultivated brains. 68

The militiamen themselves completely agreed. Seaman Henry C. Rowland of Yankee, wrote of the militia’s wasted talent: “To be logical, it is not, any more than it would be worthwhile to send the same sort of crowd to work digging a Nicaraguan canal with picks and shovels.” 69

The “cultivated brains” Hubbard referred to were some of the most adept and brilliant men of their generation, and they often demonstrated it. Yankee’s Passed Assistant Engineer, Joseph L. Gilbert, at one point declared the ship’s dynamo unfixable. A lieutenant approached Captain Brownson and informed him he knew a man who could fix it. Brownson asked “And what would one of your forecastle scrubs be apt to know about a ship’s dynamo?” A nervous man covered in gray paint and soot was called before Brownson, who asked, “What do you know about this dynamo?” The man responded “I know all there is to know about it, sir… I designed it, sir, at the Edison Works in Schenectady, where it was made.” 70 At Key West, one of the men assigned to rowing Brownson’s whaleboat jumped out to assist another man having an epileptic fit. An outraged Brownson demanded the sailor explain how he felt qualified to render treatment. It turned out the able bodied seaman was a graduate of Yale Medical School. 71

There was no greater example of the heights of Naval Militia success than that of the armed yacht Gloucester, formerly J. P. Morgan’s personal yacht Corsair. Gloucester’s crew, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Richard Wainwright, were the Navy’s own “Rough Riders.” Wainwright, the former Executive Officer on the battleship Maine, was offered command of Gloucester at the New York Navy Yard shortly before the war. He jumped at the chance and told the Navy Department, “never mind the armor… The boat is fast; give me guns and men–they will be the best protection.” 72Wainwright did not have to go far to find the men. His officers were friends from the Naval Academy who had since retired from the Navy. He used veteran warrant officers, and filled out the rest of his crew with local volunteers from the New York Naval Militia. His list of officers included: Lt. Thomas C. Wood, President of the Ball and Wood Co. of New York, and En. John Tracy Edson, the Chief Medical Examiner at the Equitable Life Insurance Company. Both graduated the Academy with Wainwright in 1871. They were joined by international renowned polo player and millionaire, Lt. George Norman, whose personal attorney was none other than Secretary Long. Their assistant paymaster, Alexander Brown, was a partner at a Philadelphia bank, and one of the ship’s machinists was the superintendent of a bicycle factory. The all-volunteer crew distinguished itself in many engagements, the most prominent of which was defeating the Spanish torpedo destroyers Plutón and Furor on 3 July 1898, at the Battle of Santiago Bay. After the battle, crewmen, under Edson’s command, rescued the Spanish sailors from the burning and sinking torpedo-destroyers and the cruiser Infanta Maria Teresa. Edson personally received the surrender of Admiral Cervera himself. 73

Henry Barrett Chamberlin of the Chicago Record wrote of Gloucester’s crew: “This is but a glance at a part of the personnel of an American fighting ship hastily recruited when hostilities begun, but it tells the reason Wainwright succeeded. His crew was thoroughbred.” Of course that same “thoroughbred” crew had no intention of remaining in the Navy, and officers and men on the Gloucester suggested that Norman, “instruct his attorney to advocate the sending home of the vessel now that war is at an end and muster out the ships complement desirous of resuming the business of life ashore.” 74

Conclusion

After the war it was clear that a longer and larger conflict with more resolute adversaries would be far less forgiving of these underqualified sailors and the misallocation of skilled men. Seaman Rowland of Yankee reflected on this fact in 1928, writing:

Wartime expediency requires that each individual serve in the capacity for which he is best trained, where he can be of greatest use. There is ample room for all in the various Corps, or at least there would be in a war of any magnitude, and once war is declared no man can say to what size it may grow or when and where it may end. 75

Secretary Long took the lessons of 1898 to heart and once again attempted to pass a Naval Reserve Bill to create a reservist force of militiamen and retired sailors, but Congress rejected it in 1900. It took another 15 years and the immediate needs posed by an entire world at war to break the apathy before Congress approved the formation of a Naval Reserve in 1915. 76

The sailors enlisted, or in the case of merchantmen – employed – to fight the Spanish-American War remain unique outliers in American Naval history. Their experiences, and the controversy surrounding their enlistment, were the product of an American Navy in transition: technologically, administratively, and culturally. Ultimately, the service of these foreigners, pirates and amateurs were symptom of sudden crisis amidst the United States Navy’s rocky evolution from post-Civil War coastal defense malaise to a 20th century global fighting force.

(Return to April 2016 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

- Lt. George L. Dyer to Cmdr. Richardson Clover, 16 April 1898, RG 313, Entry 47, National Archives, Washington DC. ↩

- Basilio Agustin y Dávila Proclamation, 23 April 1898, Area File of the Naval Records Collection, M625, Roll 363, National Archives Washington, DC. Dewey, rather proud of his crew of “foreigners,” thought the Governor-General’s words would incite a fighting spirit. He had them read aloud on the way to Manila over the laughs and jeers of Olympia’s crew. Ronald Spector, Admiral of the New Empire, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1974), 56. ↩

- Both Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete and Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasarón were openly defeatist in their correspondence and neither believed that the United States demonstrated any weakness due to the make-up of its enlisted force. Montojo to Bermejo, 1 May 1898, RG 45, Entry 464, National Archives, Washington, DC; and “Views of Admiral Cervera Regarding the Spanish Navy in the Late War,” Office of Naval Intelligence Information from Abroad (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1898). ↩

- For example, David Trask’s The War with Spain in 1898; probably the most thorough book on the war, provides a detailed picture of the multiracial United States Army force that attacked Cuba and Puerto Rico, but makes little mention of the enlisted Naval Force. Instead he focuses exclusively on officers. David Trask, The War with Spain in 1898 (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1981). Frederick S. Harrod’s Manning the New Navy: The Development of a Modern Naval Enlisted Force, 1899-1940, comes the closest to tackling the state of the enlisted force, but provides only a generalized description of the decades after the Civil War and begins in earnest the year after the Spanish-American War. Frederick S. Harrod, Manning the New Navy: The Development of a Modern Naval Enlisted Force, 1899-1940 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1978). It seems that the historical neglect for enlisted contributions began during the war itself and invited comment even then. The Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, Commdore Arent S Crowninshield, wrote to Rear Admiral William T. Sampson on June 23, 1898, to inform him that: “Not reporting the names of men with officers, among the loss in killed and wounded, causes much newspaper comment.” Crowninshield to Sampson, June 23, 1898, RG 80, Entry 194, vol. 1, p. 219, National Archive, Washington, DC. ↩

- Chief of the Bureau of Navigation Arent S. Crowninshield to Commodores Francis M. Bunce, Henry L. Howison, and John A. Howell, 3 March 1898, RG 45, Entry 28, p. 331, National Archives, Washington, DC; and Crowninshield to Captain William T. Sampson, 5 April 1898, RG 45, Entry 29, p. 203, National Archives, Washington, DC. For a list of the vessels commissioned and recommissioned to serve in the Asiatic and North Atlantic Fleets, and on the Pacific Station, see: Appendix to the Report of the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, 1898 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Officer, 1898), 38-43. This list only includes vessels in the blue water Navy and excludes dozens of other vessels from the Auxiliary Fleet under Rear Admiral Henry Erben on the Atlantic Coast of the United States. ↩

- Frederick S. Harrod, Manning the New Navy: The Development of a Modern Naval Enlisted Force, 1899-1940 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1978), 34. ↩

- In an address to the Naval War College on 18 June 1897, Charles H. Cramp, Esq stated: “The naval armament of today is a mechanism… For this reason the word seamanship, in the old fashioned or conventional sense, has ceased to cover adequately the requirements of knowledge, skill, and aptness, which the modern conditions of naval warfare impose upon the officer in command of subordinate.” Charles H. Cramp, “The Necessity of Experience to Efficiency, 18 June 1897,” (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1897), 4. After the war, Secretary of the Navy John D. Long noted that retaining qualified sailors was an imperative. His first order to the European and Asiatic Stations Commanders in January 1898, was to, “retain men whose enlistments were about to expire.” Annual Report of the Navy Department, The Year 1898 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Officer, 1899), 325. ↩

- Frederick S. Harrod, Manning the New Navy: The Development of a Modern Naval Enlisted Force, 1899-1940 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1978), 15; and “Testimony taken by the Joint Subcommittee of the Committees on Naval Affairs of the Senate and the House of Representatives, Pursuant to the Following Joint Resolution of January 12, 1894,” (Washington: Government Printing Officer, 1894), 244. ↩

- “Testimony taken by the Joint Subcommittee of the Committees on Naval Affairs of the Senate and the House of Representatives, Pursuant to the Following Joint Resolution of January 12, 1894,” (Washington: Government Printing Officer, 1894), 250. ↩

- Less than 1 in every 100 officers commissioned between 1845 and 1915 was a promoted enlisted sailor. Peter Karsten, The Naval Aristocracy The Golden Age of Annapolis and the Emergence of Modern Navalism (New York: The Free Press, 1972), 13. ↩

- Machinist Mate Rufus Steele explained his fellow enlisted men’s dissatisfaction to the Joint Subcommittee on Naval Affairs. He, a machinist mate on a man-of-war, could only earn $1,800 over a year of sea duty at the end of his naval career. Beginning machinists in the merchant marine earned as much as $1,500 per years and changed employers at will. Merchantmen also promoted. A machinist mate could become a ship’s engineer or assistant engineer, the equivalent rank and responsibility of a deck or engineering officer on a naval vessel. “Testimony taken by the Joint Subcommittee of the Committees on Naval Affairs of the Senate and the House of Representatives, Pursuant to the Following Joint Resolution of January 12, 1894,” (Washington: Government Printing Officer, 1894), 226, 240. ↩

- Frederick S. Harrod, Manning the New Navy: The Development of a Modern Naval Enlisted Force, 1899-1940 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1978), 17-18. ↩

- Frederick S. Harrod, Manning the New Navy: The Development of a Modern Naval Enlisted Force, 1899-1940 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1978), 8-9, 18. ↩

- “Enlistment, Training, and Organization of Crews for Our New Ships,” United States Naval Institute 1891, Published by Naval Historical Foundation, 1972, 17. ↩

- Frederick S. Harrod, Manning the New Navy: The Development of a Modern Naval Enlisted Force, 1899-1940 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1978), 18. ↩

- Messenger at least admits that foreign sailors were far more likely to re-enlist, usually after visiting relatives abroad. “Testimony taken by the Joint Subcommittee of the Committees on Naval Affairs of the Senate and the House of Representatives, Pursuant to the Following Joint Resolution of January 12, 1894,” (Washington: Government Printing Officer, 1894), 214-215. ↩

- Crowninshield to Remey, RG313, Entry 72, National Archives, Washington, DC. ↩

- The Spanish were not above planting false rumors. Spanish agents in Victoria, British Columbia, spread rumors of a Spanish privateer off the Canadian Pacific Coast. The phantom privateer planned to capture American ships carrying gold from the Yukon. The United States was concerned enough to request that the British government investigate the possibility. P. M. Sherrin, “Spanish Spies in Victoria, 1898,” BC Studies, No. 36, Winter 1976-1977, 23-33. ↩

- Schley to Crowninshield, 6 April 1898, RG 313, Entry 68, National Archives, Washington, DC. ↩

- Old Weather Forum, “CREW of USS Concord. (PG-3) May 1897 onwards,” accessed on May 1, 2015, http://forum.oldweather.org/index.php?topic=4125.0. ↩

- Frederick S. Harrod, Manning the New Navy: The Development of a Modern Naval Enlisted Force, 1899-1940 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1978). ↩

- The number of Chinese sailors in Dewey’s fleet increased after the purchase of the steamers Nashan and Zafiro. Both ships had British captains and Chinese crews who continued to Manila as contractors under American naval officers. Benjamin R. Beede, The War of 1898 and U.S. Interventions 1898-1934: An Encyclopedia (New York: Routledge, 1994), 102. ↩

- Dewey to Dewey, 23 January 1898, Papers of George Goodwin Dewey, Box 1, Jan-Mar 1898, Archives of the United States Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, DC. ↩

- “Dewey’s Chinese Seaman,” New York Times, February 23, 1899. ↩

- The Navy eventually got the men they wanted with an expensive national program of targeted enlistment, but this did not come until after the Spanish-American War. This campaign is the topic of Frederick S. Harrod, Manning the New Navy: The Development of a Modern Naval Enlisted Force, 1899-1940 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1978). ↩

- President William McKinley transferred command of the Treasury Department’s Revenue Cutter Service, precursor to the Coast Guard, to the Secretary of the Navy for the duration of the war. This included the ships, officers, and crews. These men served fluidly and with distinction alongside regular naval vessels in the Philippines, on both American Coasts, and in the Caribbean. There are many examples of contributions by Revenue Cutter Service vessels and crews. McCulloch was with Dewey at Manila Bay, Hudson rescued the torpedo boat Winslow while under heavy fire, and Manning, Windom, Morrill, and Guthrie all saw battle in the Caribbean. The defense of the Pacific Coast was almost entirely reliant on Revenue Cutters. McKinley to Gage, 24 March 1898, Records of the United States Coast Guard; Records Relating to Operations; Revenue Cutter Service; Operations “Spanish American War;” RG26; and Appendix to the Report of the Bureau of Navigation, 1898, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1898), 141-44. ↩

- William H. Flayhart III, The American Line (1871-1902) (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000), 257-258, 262. ↩

- Cotton to Long, 13 May 1898, Area File of the Naval Records Collect, M625, roll 229, National Archives, Washington, DC. ↩

- Cotton to Long, 13 May 1898, Area File of the Naval Records Collect, M625, roll 229, National Archives, Washington, DC. Fearing for the Harvard and its crew, Long ordered Cotton to: “Vigorously protest against being forced out of the port in the face of superior blockading force, especially as you were detained previously in the port by the French authorities because Spanish men-of-war had sailed from another port…” Appendix to the Report of the Bureau of Navigation, 1898, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1898), 383. ↩

- Goodrich commanded a merchant steamer under a United States Navy flag for a very short time in 1884. The crew was made up entirely of British sailors and Goodrich permitted the ships first officer and officers on watch to use “British merchant steamer ways.” His experiences on that ship confirmed his belief that a merchant ship in time of war could be managed by a single Naval Officer for the movement of the ship while the civilian officers performed, “minuter cares of routine and discipline.” Caspar F. Goodrich, “SCOUTS,” 29 July 1902, RG 15, NWC Lectures, 1894-1903, Box 1, pp. 7-8, Naval War College, Newport RI.

Goodrich was more than pleased with St. Louis’ crew of contractors, but believed the ship’s merchant officers deserved commissions. He wrote to Long on July 10, 1898: “If it must be give me at most, four six inch guns one forward, one aft and one on each side, with twenty more marines to man them and please send me not another soul. We are all as happy as clams on board and we only ask to be left alone. I have never commanded a more harmonious ship. I hear we are to have a Paymaster. Please countermand his orders; I have no need of him at all. The Officers accounts are taken up at some offices others on shore and those of the marines can be similarly dealt with. The business of the ship and her crew is done by the American Line purser in a business way. A Paymaster is superfluous; were one sent to replace the Purser dire confusion would result. It is but right to commission the officers (yet unexamined by the way), but it would be a great mistake, in my judgment to enlist the crew. They are content with their present status and compensation. Why alter and arrangement which has served its purpose well?” Goodrich to Long, July 10, 1898, Papers of John D. Long, Box 43, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, MA.

Goodrich was also a staunch booster for the inclusion of the Naval Militiamen on regular naval vessels. Harold Thomas Wieand, “History of the Development of the United States Naval Reserve, 1889-1941,” Submitted to the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, 1952, 61. ↩

- Goodrich to Sampson, 18 May, 1898, Area File of the Naval records Collection, M625, Roll 230, National Archives, Washington, DC. This was the second time in in a matter of months that the crew of the St. Louis, particularly, Thomas Seagrave, was singled out for praise. On February 6, 1898 the Hollande-American liner Veendam struck a wreck and began to sink. The next morning she was discovered by St. Louis, steaming west out of South Hampton. Seagrave personally lead life boat expeditions to the wounded Veendam in rough seas. He and the other officers of St. Louis rescued all of the ships passengers and crew. On reaching New York, the officers achieved celebrity and were rewarded with silver cups, and the entire crew received monetary rewards. At a March 17, 1898, ceremony Captain William G. Randle stated: “Events are transpiring now in this country which may lead us into war, and we may be called upon to sacrifice life in defense of our country. But the satisfaction will not be as great as the saving of life, which is more gratifying than the taking of it.” William H. Flayhart III, The American Line (1871-1902) (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000), 247-256. ↩

- For more on this see: Sigsbee to Long, 29 May 1898, Area File of the Naval records Collection, M625, Roll 230, National Archives, Washington, DC. Sigsbee to William T. Sampson 14 July 1898, RG 313, Entry 45, National Archive, Washington, DC; and Sigsbee to Long, 27 June 1898, George G. Cortelyou Papers, Box 68, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. ↩

- Goodrich presented a lecture at the Naval War College on 29 July 1902. He went into great detail on the success of using skilled merchantmen. He wrote: “I am informed by the port captain of the American Line that of the four big liners, the St. Louis, the only one which did not adopt navy enlistments, and routine, made more miles, did more work and more kinds of work, cost less in operation and returned in better order than any of her sisters. I have no reason for questioning the accuracy of these statements, they agree indeed with my general impression, and I have no hesitation in accounting for them by the soundness of the system adopted exclusively by the St. Louis. I may add that a happier set of officers or a more contented lot of men could hardly be found. The record of the ship is notable. She spent six weeks at sea without taking on board a ton of coal, a gallon of water (or) a pound of provisions, during which period she scouted, captured blockade runners, landed Shafter’s army, housed and fed at one time as many as two hundred sailors detached from the fleet for the landing service, cut cables, and brought seven hundred of Cervera’s men north as prisoners.” Caspar F. Goodrich, “SCOUTS,” 29 July 1902, RG 15, NWC Lectures, 1894-1903, Box 1, p. 8, Naval War College, Newport RI. ↩

- Harold Thomas Wieand, “History of the Development of the United States Naval Reserve, 1889-1941” Submitted to the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, 1952, 60. The total number of recognized Naval Militiamen in the United States in January 1898, was 4,501 enlisted men and 427 officers. This makes a wartime participation rate of 91%. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Charles H. Allen, May 20, 1898, RG 313, Entry 109, vol. 8, National Archives, Washington, DC. ↩

- President of the Naval War College Henry C. Taylor wrote to Assistant Secretary of the Navy William McAdoo on 12 December 1896, “Our deep-sea merchant shipping has disappeared and the captains and mates we obtained from it during our Civil War and who rendered such brave and intelligent service are no longer at our disposal.” Taylor suggested the use of the state Naval Militia’s to serve in their stead as coastal defense forces. Taylor to McAdoo, 12 December 1896, “Naval-Reserve Letter,” RG1, Box 3, Folder 6. Naval War College, Newport, RI; and Harold Thomas Wieand, “History of the Development of the United States Naval Reserve, 1889-1941” Submitted to the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, 1952, 11, 21. ↩

- New York in 1888, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island in 1889, California in 1891, Maryland, Vermont, and South Carolina in 1892, North Carolina, Michigan and Georgia in 1893, Illinois, Connecticut, Virginia, New Jersey and Louisiana in 1894 and Florida and Ohio both founded theirs before 1898. Harold Thomas Wieand, “History of the Development of the United States Naval Reserve, 1889-1941” Submitted to the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, 1952, 14, 35-36. ↩

- Harold Thomas Wieand, “History of the Development of the United States Naval Reserve, 1889-1941” Submitted to the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, 1952, 28, 30, 37, ↩

- Harold Thomas Wieand, “History of the Development of the United States Naval Reserve, 1889-1941” Submitted to the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, 1952, 41 ↩

- Taylor to McAdoo, 12 December 1896, “Naval-Reserve Letter,” RG1, Box 3, Folder 6, Naval War College, Newport, RI; “The Naval Militia,” Army Navy Journal, April 30, 1898; and Harold Thomas Wieand, “History of the Development of the United States Naval Reserve, 1889-1941” Submitted to the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, 1952, 44. ↩

- The earliest Naval Militia, the battalions from New York and Massachusetts, were invited to cruise during summer fleet maneuvers in the 1890s and the New York Naval Militia was given the Civil War-era New Hampshire to drill. The other state militias received little, if any, training with the regular Navy. Harold Thomas Wieand, “History of the Development of the United States Naval Reserve, 1889-1941” Submitted to the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, 1952, 39-40, 45-46; and William R. Kreh, Citizen Sailors: The U.S. Naval Reserve in War and Peace (New York: David McKay Company, Inc, 1969), 187. ↩

- Harold Thomas Wieand, “History of the Development of the United States Naval Reserve, 1889-1941” Submitted to the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, 1952, 31, 51. ↩

- Roosevelt to Long, April 15, Papers of John D. Long, Box 40, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, MA. ↩

- “The Naval Militia,” Army Navy Journal, April 30, 1898. ↩

- Harold Thomas Wieand, “History of the Development of the United States Naval Reserve, 1889-1941” Submitted to the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, 1952, 25 ↩

- “The Naval Militia,” Army Navy Journal, April 30, 1898. ↩

- Roosevelt to Long, April 15, Papers of John D. Long, Box 40, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, MA. ↩

- The Massachusetts Militia crewed Prairie, New York’s two battalions crewed Yankee and Gloucester, Michigan crewed Yosemite, Maryland crewed Dixie, and New Jersey the Badger and Resolute. “The Naval Militia,” Army Navy Journal, April 30, 1898; and William R. Kreh, Citizen Sailors: The U.S. Naval Reserve in War and Peace (New York: David McKay Company, Inc, 1969), 190. ↩

- Harold Thomas Wieand, “History of the Development of the United States Naval Reserve, 1889-1941” Submitted to the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, 1952, 59-60. ↩

- William R. Kreh, Citizen Sailors: The U.S. Naval Reserve in War and Peace (New York: David McKay Company, Inc, 1969), 188-89. ↩

- Crowninshield to Commodore George C. Remey, June 10, 1898, RG 313, Entry 72, National Archives, Washington, DC. Harold Thomas Wieand, “History of the Development of the United States Naval Reserve, 1889-1941” Submitted to the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, 1952, 60. ↩

- Brownson to Long, 28 August 1898, RG 45, Entry 464, National Archives, Washington, DC. ↩

- The U.S.S. Yankee on the Cuban Blockade (New York: Members of the Yankee’s Crew, 1928), 8. ↩

- Brownson to Long, 28 August 1898, RG 45, Entry 464, National Archives, Washington, DC. ↩

- Brownson to Long, 28 August 1898, RG 45, Entry 464, National Archives, Washington, DC. ↩

- Hubbard changed the names of the sailors in the story so as not to embarrass the men. The U.S.S. Yankee on the Cuban Blockade, (New York: Members of the Yankee’s Crew, 1928), 9. ↩

- Reamey to Crowninshield, May 13, 1898, Area File of the Naval Records Collection, M625, roll 130, National Archives, Washington, DC. ↩

- Reamey to Crowninshield, May 13, 1898, Area File of the Naval Records Collection, M625, roll 130, National Archives, Washington, DC. ↩

- Reamey to Crowninshield, May 13, 1898, Area File of the Naval Records Collection, M625, roll 130, National Archives, Washington, DC. ↩

- Long to Emory, May 11, 1898, Papers of William Emory, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. ↩

- Joseph S. Stringham, The Story of the USS Yosemite (Detroit: Self-published, 1929), 22. ↩

- Henry B. Joy, The U.S.S. Yosemite, Purisima Concepcion Incident, June 16, 1898 (Detroit: Self-published, 1937), 6-7. ↩

- Emory’s Report of July 18, 1898, Papers of William Emory, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. ↩

- Harold Thomas Wieand, “History of the Development of the United States Naval Reserve, 1889-1941” Submitted to the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, 1952, 36. ↩

- Charles J. Train to John D. Long, 15 September 1898, RG 45, Entry 46, National Archives, Washington, DC. ↩

- Charles J. Train to John D. Long, 15 September 1898, RG 45, Entry 46, National Archives, Washington, DC. ↩

- Brownson to Long, 28 August 1898, RG 45, Entry 464, National Archives, Washington, DC. ↩

- Long to Sampson, 15 July 1898, RG 80, Entry 194, vol. 1, pp. 281-284, National Archives, Washington, DC. ↩

- The U.S.S. Yankee on the Cuban Blockade (New York: Members of the Yankee’s Crew, 1928), 6. ↩

- The U.S.S. Yankee on the Cuban Blockade (New York: Members of the Yankee’s Crew, 1928), 28. ↩

- The U.S.S. Yankee on the Cuban Blockade (New York: Members of the Yankee’s Crew, 1928), 30-31. ↩

- The U.S.S. Yankee on the Cuban Blockade (New York: Members of the Yankee’s Crew, 1928), 33. ↩

- Henry Barrett Chamberlin, “Wainwright’s Men,” The Chicago Record’s War Stories (Chicago: Chicago Record, 1898), 146-47. Wainwright’s request was approved by his friend, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt. Damon E. Cummings, Admiral Richard Wainwright and the United States Fleet (Washington, DC: Government Printing Officer, 1962), 93. ↩

- Henry Barrett Chamberlin, “Wainwright’s Men,” The Chicago Record’s War Stories (Chicago: Chicago Record, 1898), 146-47; ↩

- Henry Barrett Chamberlin, “Wainwright’s Men,” The Chicago Record’s War Stories (Chicago: Chicago Record, 1898), 146-47; and Damon E. Cummings, Admiral Richard Wainwright and the United States Fleet (Washington, DC: Government Printing Officer, 1962), 95. ↩

- The U.S.S. Yankee on the Cuban Blockade, (New York: Members of the Yankee’s Crew, 1928), 34. ↩

- Annual Report of the Navy Department, The Year 1898 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Officer, 1899), 135-36; and Harold Thomas Wieand, “The History of the Development of the United States Naval Reserve, 1889-1941” (PhD diss., University of Pittsburgh, 1952), 68. ↩