Contents:

Introduction

Mahanian Maritime Theory Pertaining to the Value of Hawai’i (1892-1895)

Theodore Roosevelt and Domestic Perceptions of the Annexation of Hawai’i – The Short Story

Conclusion

Bibliography

By Ambjörn L. Adomeit 1

Candidate (Civilian), Master of Arts in War Studies

The Royal Military College of Canada

“… [W]ithout some such governmental care as is implied by an organized institution, it is vain to hope for the development of the art of naval war.”

– Alfred Thayer Mahan, Captain, U.S.N. 2“It is not too much to say that Captain Mahan was doing for Naval Science what Jomini did for Military Science.”

– Rear Admiral S.B. Luce 3

Introduction

Whatever the incidental benefits the annexation of Hawai’i brought to the United States, the primary value the Hawaiian archipelago held for the nation was military-strategic. Hawai’i, as an island, a current state, and as the source of some of the United States’ greatest cultural treasures, brought economic and cultural expansion to the nation; but as valuable as it is in these respects, it was very keenly perceived as a military asset from the outset. This essay focuses on the Mahanian interpretation of the military value of Hawai’i rather than the political aspects of the annexation process (including the various motivations behind the annexation campaign run by Theodore Roosevelt and his supporters).

I examine the issue of Hawaiian military value assessment in two blocks of time. The first lies between 1892 and 1895, the period during which Mahan was developing his initial strategic appraisals of Hawai’i. The second falls between 1898 and 1910, the period immediately following the United States of America’s annexation of Hawai’i; this latter period covers the administrations of Presidents McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt. While cited sources span this period, the key years for consideration are 1908-1910, the period during which the United States Navy was formalising its doctrines on the use of Hawai’i within American maritime strategic theory. 4

Mahanian Maritime Theory Pertaining to the Value of Hawai’i (1892-1895)

Alfred Thayer Mahan, one of the United States’ most renowned naval theoreticians, argued that Hawai’i’s central location between the American mainland and the Asian-Pacific theatre made it desirable both as an operational launching point and as a defensible fall-back position, and Theodore Roosevelt 5 and his advisory clique 6 fought ardently for Hawaiian annexation. As early as 22 January 1886, Mahan was considering the role “… military ports in various parts of the world …” would have in maritime theory, and in particular the maritime strategies of the United States across the oceans of the world. 7 This would become a preoccupation of his spanning several years.

While the Hawaiian Islands were isolated from any nearby continental landmasses, Mahan illustrated the value the islands held as a stopover point for American vessels seeking to reach the Philippines or San Francisco from either side of the Pacific Ocean in 1893. 8 He pointed out that sea lines of communication (SLOC) and shipping routes naturally focussed upon Honolulu as a staging point for the trans-Pacific voyage, and that Pearl Harbor was a naturally impregnable harbour, perfect for a naval base. 9

In Mahan’s perspective, Hawai’i served as a bulwark against Chinese expansion across the Pacific Ocean. He drew a comparison between Hawai’i and the Western European States: Germany, France, et cetera created a defensive bulwark between the Chinese and the United States should they attempt to cross the European and Asian continents by land, and that the use of Hawai’i as a naval staging point served a similar purpose, utilizing the open expanses of the Pacific Ocean as a bulwark, instead of land. In other words, he argued that the states of Continental Europe created a buffer between the “barbarian Chinese” and the United States. From a practical standpoint, the hundreds of millions of Europeans standing between America and its potential enemies in the east provided the United States with a standing defence force for which it did not have to pay. Mahan argued that the Hawaiian archipelago existed in a position of natural strategic relevance given sea-and-wind currents in the mid-Pacific and was located centrally to the Pacific theatre, to San Francisco (America’s major naval port on the west coast), and to Australia and New Zealand.

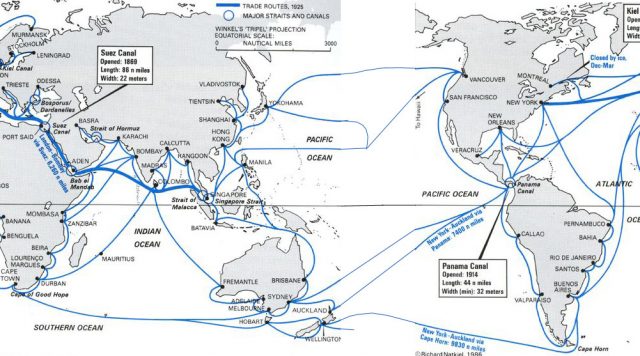

MAP 1: Mean Global Surface Currents. 10

MAP 2: Global SLOC “Choke Points.” 11

Senator George Clement Perkins wrote a letter addressed to Mahan on 7 January 1911 urging him to give to the United States Senate Committee on Naval Affairs an overview of his views on the transfer of one half of the USN battleship fleet to the west coast. The letter stated that “… the people of the Pacific Coast …. are nowise apprehensive that there is danger of attack, but that the commercial expansion of Oriental powers … has transferred from the Atlantic to the Pacific the elements of discord …. They believe … the United States should be represented by a fleet commensurate in strength with our interests in that part of the world.” 15 As we will see below, Mahan obliged.

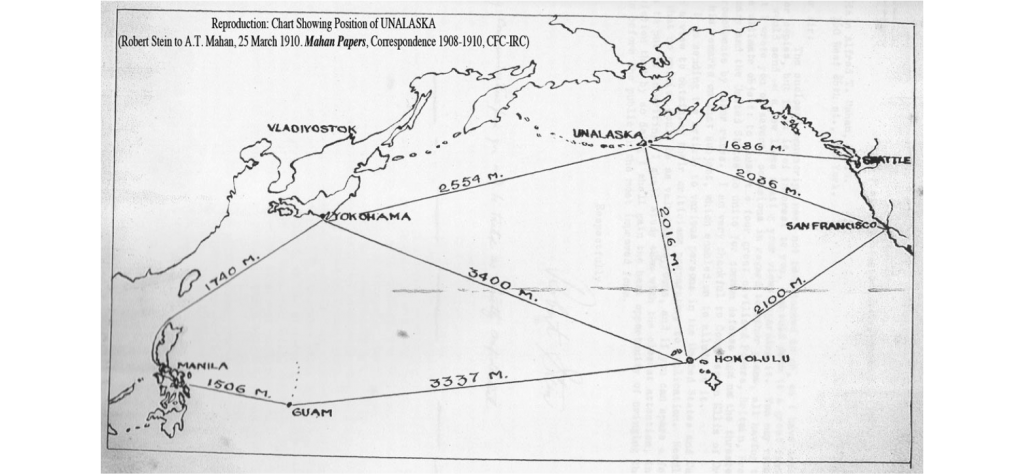

While many viewed Hawai’i to be a key strategic point, others, such as Robert Stein (a failed polar explorer), argued that Alaska was far more valuable to the United States than Hawai’i. Stein’s communications with Mahan prove to be a most concise and insightful contemporary critique of Mahan’s argument: Hawai’i, Stein argued, had fewer vital mineral resources than Alaska:

Between 1880 and 1908 [Alaska] yielded $147,972,701 worth in minerals alone. Its known coalfields contain 7 billion tons of coal, 3 billions more than the total output of Pennsylvania to date, and the area that has been prospected for coal is only one-tenth of the total. 16

Furthermore, Stein argued that every point in favour of Hawaiian strategic value needed to be re-emphasised with regard to Alaska, particularly the Aleutian Islands and Alaska’s southern coast. His argument was that any fleet operating off of the Aleutians (most likely the Japanese, though he refrained from explicitly naming a potential belligerent) would be within easy striking distance of both Seattle and of San Francisco:

… [O]ur naval authorities have selected Kiska Island, one of the most southerly of the Aleutians, and the most centrally located, for a naval reservation, but nothing has yet been done to make it available as such, for the good reason that no money has been appropriated for the purpose. If the enemy cared to be ironical [sic.], they could convert that very naval reservation into an impregnable naval base for themselves, where their men-of-war could recoal from their colliers in perfect security. 17

He asserted that the lack of military support in Alaska opened the entire area to enemy invasion: Stein stated that by not establishing a naval presence firmly and obviously in Alaskan waters, America was inviting invasion. The rich coalfields in the region were undefended, and would be of manifest value for an invasion fleet, and of manifold loss to the capacities of the USN should they be lost in such a manner. He encouraged not only a maritime presence in the region, but also a connecting railroad between the contiguous American states and Alaska to further exploit and defend Alaskan mineral assets. 18 It bears mentioning that while Mahan’s strategic assessments were generally based in the projection of “hard” and “soft” maritime power (combat capacities and political influence, respectively), Stein took a decidedly self-defensive approach in his own assessments. 19

Sadly, for Stein’s argument at any rate, Mahan had indeed acknowledged the value of Alaska in his assessment, but determined that while Alaska was a strategically situated location for an attack across the northern Pacific Ocean, it was of less strategic importance than Hawai’i. Some of Mahan’s research notes, likely written before Stein sent his essay to the theorist in 1910, state:

It is undoubtedly desirable to have stations in Alaska … where a supply of coal could be obtained by the fleet when colliers might fail, but it is a question whether such stations should be fortified or equipped for repairing and administering to the needs of the fleet. It is believed that if the fleet itself with its auxiliaries of … [ships] … could not hold outlying stations and thus maintain itself there would be little advantage in fortifying such stations for its protection or in providing an elaborate plant for its maintenance. 20, pp. 2, The Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan, archived microfilm collection (United States of America Library of Congress), courtesy of the Canadian Forces College IRC, Toronto, Ontario.]

Mahan’s concern was that any naval port fortified in Alaskan territory would result in a mis-placement of strategically needed resources. Because of its proximity to the contiguous United States, a flotilla could be dispatched to defend Alaskan waters with sufficient speed to mitigate any potential foothold a belligerent could gain in such a short time. The wireless telegraph held extreme importance for Mahanian maritime theory: it permitted far greater flexibility in determining deployments and in operational strategy. 21 Mahan also argued that the vast difference in population sizes between the United States and Canada (cited as sixty-five million to six million, respectively) must be borne heavily in consideration when assessing the annexation of either Hawai’i or Alaska for American interests, and thereby interrupting Great Britain’s commercial interests in the Pacific as well. 22 Further, Mahan illustrated the intrinsic strategic value of the Hawaiian archipelago as a refuelling station beyond that of any Alaskan island:

Shut out from the Sandwich Islands as a coal base, an enemy is thrown back for supplies of fuel to distances of thirty-five hundred or four thousand miles, – or between seven thousand and eight thousand, going and coming, – an impediment to sustained maritime operations well-nigh prohibitive. 23

British trading routes between British Columbia, Australia and New Zealand, and the South China Sea all relied upon Hawai’i as a refuelling station and for maintenance. Any belligerent fleet possessing Hawai’i would be able to fall back a safe distance from the front lines for refuelling and repairs while not removing itself from the battle. On the other hand, any vessel following the Alaskan coastline would be in constant danger of being out of reach of its refuelling station(s) and would be at severe risk of being surrounded at any point.

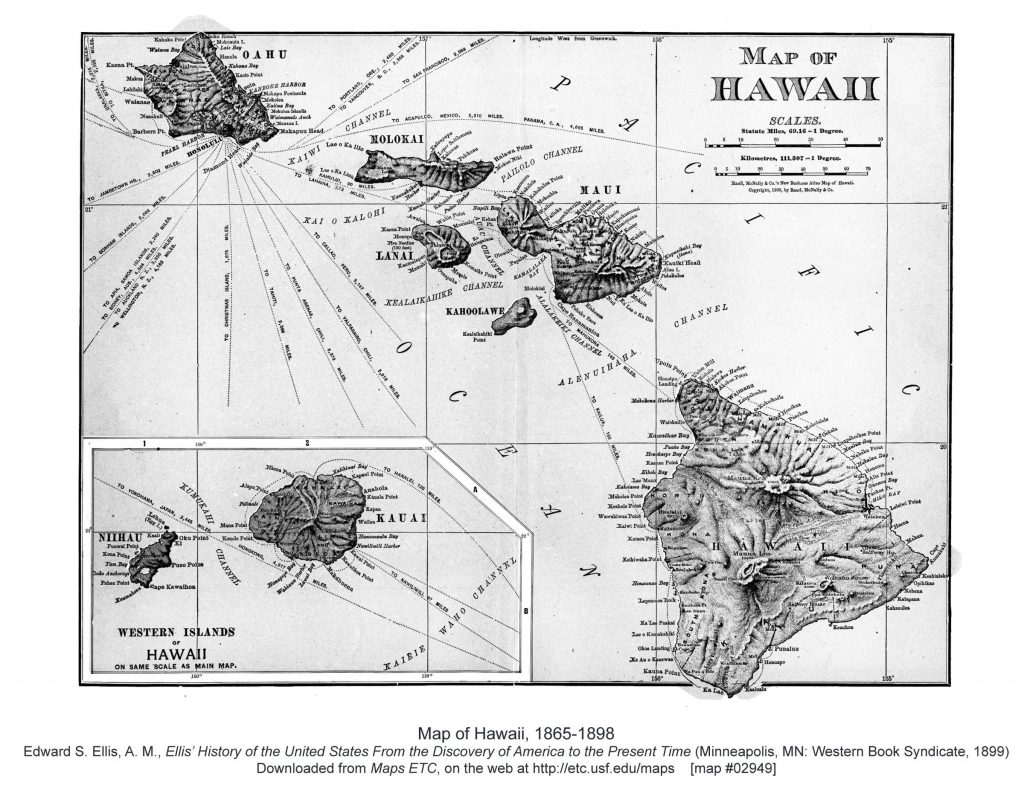

MAP 3: The Hawaiian Islands 24

As well intended as Stein’s arguments were, his grasp of maritime strategy failed to account for forces and considerations outside the control of the United States’ government and interests. Failing to account for British interests and how British trading history in the Pacific Ocean had developed over time, resulted in a blinkering of Stein’s strategic vision. Another example is raised by Peter Karsten in his article “The Nature of ‘Influence’: Roosevelt, Mahan and the Concept of Sea Power.” 26 Roosevelt was an independent thinker and strove to understand as much as he could about any given topic: he did not constrain himself to a small grouping of advisors and supporters. In fact, he occasionally went around his advisory clique and drew upon the expertise of those who could contribute to his own learning. For instance, as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt urged a war with the Spanish in the Caribbean, and sent a plan to Mahan for review. This plan had been composed by Captain Caspar Goodrich, and had been roundly criticized by Roosevelt before its hand-off to Mahan. As Karsten comments:

[In late 1897] Roosevelt had sent Goodrich a problem in strategy: “Japan makes demands on Hawaiian Islands. This country [the United States] intervenes. What force will be necessary to uphold the intervention, and how shall it be employed?”Goodrich argued that the Navy should carry an army of occupation to the Islands. Roosevelt disagreed. “It seems to me,” he replied, “that the determining factor in any war with Japan would be the control of the sea, and not the presence of troops in Hawai’i. If we smash the Japanese Navy … then the presence of a Japanese army corps in Hawai’i would merely mean the establishment of Hawai’i as a half-way post for that army corps on its way to our prisons. If we didn’t get control of the seas then no troops that we would be able to land … could hold Hawai’i against the Japanese ….” 27

Karsten’s observation that Roosevelt’s timing indicates he was testing Mahan’s analytical ability is extremely persuasive. There is evidence that Roosevelt eventually broke with Mahan as his own influence in the upper political echelons of the United States mounted and his own analytical ability was given greater and greater weight. Roosevelt’s use of Goodrich to test Mahan is an early indicator of this break, though Roosevelt did agree with Mahan’s assessment. 28 These examples of strategic assessment and critique underscore the value strategists must place in historical analysis of a region when developing operational guidelines and global strategy: the loss of any contextual element risks an entire military enterprise. 29

These assessments are borne out even today. In an article dated 11 November 2009, Professor James Holmes of the United States Naval War College wrote, “[t]he open sea resembled a featureless plain, with few important geographic assets. The rarer these features, the more valuable. If there was only one island or archipelago, it held matchless strategic value.”

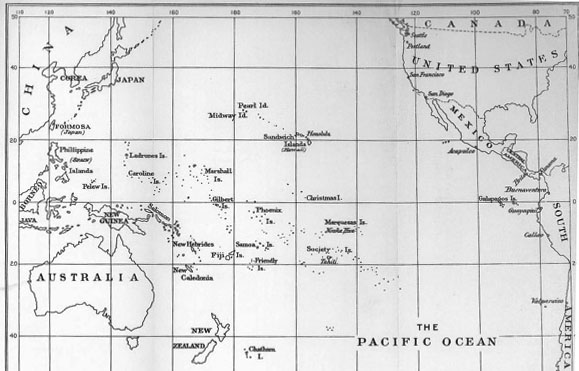

MAP 4: The Pacific Theatre Sea Lines of Communication, North Hemisphere 30

Theodore Roosevelt and Domestic Perceptions of the Annexation of Hawai’i – The Short Story

Theodore Roosevelt believed strongly that Hawai’i needed to be annexed by the United States and that a canal connecting Atlantic SLOC and Pacific SLOC needed to be built, and agreed with Mahan on this point, as did the American Representative to Hawaii, John L. Stevens. 34

MAP 5: The Pacific Theatre 2 35

After sending a celebratory note to Mahan stating that Secretary of the Navy John D. Long supported Hawaiian annexation, Roosevelt commented in a letter to Henry Cabot Lodge, “[y]ou must get Manila [sic.] and Hawai’i … you must prevent any talk of peace until we get Porto [sic.] Rico and the Philippines as well as secure the independence of Cuba ….” 46 Lodge replied on 15 June, 1898,

I have, I think, done something to force Hawai’i to the front, and the House votes on it tomorrow. It will carry there by a large majority, and I do not believe the Senate can hold out very long, for the President has been very firm about it and means to annex the Islands in any way. I consider the Hawaiian business as practically settled. The whole policy of annexation is growing rapidly …. 47

Mahan’s influence did not extend far into the House of Representatives or into United States politics proper. Rather, his strategic thought and influence operated on the foundation of personal appeal and charisma, whether his own or that of those who went to him for advice. Mahan was not a particularly political creature, especially when compared to those whom he mentored, such as Roosevelt and Lodge. Instead, he preferred to make his views known and let others advocate for them rather than doing that sort of dirty work for himself; Mahan preferred his ivory tower to the political arena.

Prior to 1900, many sources – including the letters and papers compiled by Henry Cabot Lodge on Roosevelt’s behalf – seem to favour the impression that Roosevelt was dedicated to the annexation of Hawai’i without pause. Yet, in a letter dated 8 June 1911, Roosevelt wrote to Mahan commenting, “I do not believe this nation is prepared to arbitrate such questions as whether it shall fortify the [Panama] canal, as to whether it shall retain Hawai’i, nor yet to arbitrate the Monroe Doctrine, nor the right to exclude immigrants if it thinks it wise to do so.” 48 A known Hawk, Roosevelt’s diplomatic skills are just as renowned as his expansionist policies; as President of the United States, Roosevelt executed his role with wisdom rather than the fanaticism characteristic of his youth. In this note to Mahan, one of his closest advisors, Roosevelt shows a tempering of character atypical of his earlier life and shows the characteristics of the great statesman one expects when pursuing Rooseveltian studies. It shows, too, that his understanding of international and domestic sentiments had become very refined during the years of his Presidency. Early in his political career, Roosevelt had been described by his superior, Secretary of the Navy John D. Long, as a man whose impulsiveness shook the validity of his “… good judgement and discretion.” 49 Clearly, by the time Roosevelt had risen to international prominence, this impulsiveness had been tempered by experience.

The treaty under which the annexation took place provided that any revenue raised by the Hawaiian Islands be “… used solely for the benefit of the inhabitants of the Hawaiian Islands and other public pursuits.” 50 American shipping accounted for some 82.52% of Hawaiian imports in 1896, while Hawaiian-registered ships were responsible for only 5.26% of their import shipping. These vessels themselves were largely owned and operated by American-owned companies. 51 The United States reportedly consumed 92.26% of Hawaiian exports in 1896. 52 Clearly, this commercial relationship between Hawai’i and the United States, combined with extant educational sponsorship from American sources for Hawaiian schools, for instance, indicates that a formal relationship was beneficial to the United States. It speaks as well to the relationship between the United States and the Hawaiians, insofar as they would eventually benefit from full statehood and greater security than could have – arguably – been achieved under the continued rule of Queen Lili’uokalani, the deposed Hawaiian Head of State. 51

Arguments levelled against the annexation process were rather sweeping in their precision: for instance, Longfield Gorman authored a piece in The North American Review arguing that Section 1 of Article 14 and Article 15 of the United States Constitution necessitated that all Hawaiian-born American citizens be deported, for those sections prevented efficient naturalisation of annexed territories and their populations. 54 He pointed out that there was no similar impediment to Japanese immigration, and argued that President McKinley’s administration was not prepared to face the strategic nor the political implications of such potential security issues. 55

Conclusion

This essay has examined Alfred Thayer Mahan’s strategic assessments of Hawai’i as a forward maritime base in the mid-Pacific to the exclusion of political – and civilian – concerns in general. The benefit of this approach is that we can see the multi-faceted approach the United States’ most renowned naval theoretician brought to his work, affording us a clearer conception of the goals he promoted and the policies his supporters brought to the broader body of contemporary American politics. Even though this essay has not dealt with the political side of the Hawaiian Annexation in any great degree, we can nevertheless see how Mahan’s thought influenced the rationale underscoring these policies. The weakness in this approach stems from the inherent isolation in which this Mahanian analysis is presented, decontextualizing to an extent the significance of his assessments of the Hawaiian question within the broader American geopolitical and economic discourse of the day.

Hawaiian Annexation was founded upon the desire for military expansion. Two of the Hawaiian Annexation’s greatest advocates, Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge, fought tooth-and-nail to justify, rationalize, and develop plans for the annexation of the Hawaiian archipelago to support the ideologies of manifest destiny and American exceptionalism. Underscoring these political arguments, however, is an explicitly imperialistic undertone, developed in a military manner specifically intended to defend the United States’ interests in the Pacific Ocean, both in terms of national defence and in terms of economic expansion. Alfred Thayer Mahan’s capacity to make truisms of naval strategy understandable to the layman played strongly into the hands of those who wielded his theories to expand and protect American interests. It was in this manner that Mahan’s identification of the Hawaiian archipelago as the central (and thus the most strategically significant) nexus for passage across the Pacific came to the forefront of American attention. Hawai’i, occupying a place central to natural sea lines of communication (wind patterns, water movements, etc.) and their accompanying maritime trade routes, was littered with coves and harbours easily adapted to the needs of a navy in both attack and defence. Mahan identified in clear terms – for the first time – the precise reasons why Hawai’i was strategically significant, and produced evidence that supported his arguments. Without Mahan’s accurate analysis and the support he gained from eminent statesmen of the day, Hawai’i may have gone unnoticed and unappreciated for decades, or, worse for American interests, it may have fallen into the hands of possible potential enemies.

Bibliography

Primary Documents, Memoirs, Correspondence Collections:

Only entire primary documents and collections are listed here: for detailed information pertaining to specific letters/correspondence, please see the included endnotes.

Gorman, Longman. “The Administration and Hawai’i.” The North American Review (1821-1940). American Periodicals, Vol. 165, No. 490, pp. 379.

Lodge, Henry Cabot (ed.). Selections from the Correspondence of Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge, 1884-1918, Vol. I. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925.

_ _ _ _ _. Selections from the Correspondence of Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge, 1884-1918, Vol. II. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925.

Mahan, Alfred Thayer. The Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Company, Limited, 1897 (Kindle E-Book Edition).

Maine Farmer (1844-1900), “Annexation of Hawai’i,” 24 June 1897. American Periodicals, Vol. 65, No. 34, pp. 4.

Morison, Elting E, John M. Blum and John J. Buckley (eds.). The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt: Volume I – The Years of Preparation, 1868-1898. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1951.

Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan, The. Archived microfilm collection (United States of American Library of Congress), Courtesy of the Canadian Forces College Information Resource Centre, Toronto, Ontario.

Seager, Robert and Doris D. Magquire (eds.) Letters and Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan, Vol. 3. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1975.

Times, The (London, England), 24 November 1909 (reprinted Academic OneFile, 24 November 1992, News, pp. 19). Accessed 2 March 2014. (http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA116241233&v=2.1&u=lond95336&it=r&p=AONE&sw=w&asid=676074f6769665453ebbb31eaf782473).

Rice, Wallace. “Some Current Fallacies of Captain Mahan.” The Dial: A Semi-Monthly Journal of Literary Criticism, Discussion, and Information (1880-1929), Vol. 330 (16 March 1900).

Secondary Sources: Articles, Essays, Books/Monographs:

Beach, Edward L. The United States Navy: 200 Years. New York: Henry Hold and Company, 1986.

Beale, Howard K. Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of America to World Power (The Albert Shaw Lectures on Diplomatic History, 1953). Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1956.

Braisted, William R. “The Philippine Naval Base Problem, 1898-1909.” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 41, No. 1 (June 1954), pp. 21-40.

Coletta, Paolo E. “Untitled Review of Richard W. Turk, The Ambiguous Relationship: Theodore Roosevelt and Alfred Thayer Mahan.” American Historical Review, Vol. 93, No. 5 (Dec. 1988), pp. 1413-1414.

Corgan, Michael T. “Review Article: Mahan and Theodore Roosevelt – The Assessment of Influence.” Naval War College Review, Vol. 33, No. 6 (Nov.-Dec. 1980), pp. 89-97.

Dukas, Neil Bernard. A Military History of Sovereign Hawai’i. Honolulu, HI: Mutual Publishing, 2004.

Fry, Joseph A. “Feature Review: The Architects of the ‘Large Policy’ Plus Two.” Diplomatic History, Vol. 29, No. 1 (January 2005), pp. 185-188.

Garrett, Wendell D. “John Davis Long, Secretary of the Navy, 1897-1902: A Study in Changing Political Alignments.” The New England Quarterly, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Sept. 1958), pp. 291-311.

Hodge, Carl Cavanagh. “A Whiff of Cordite: Theodore Roosevelt and the Transoceanic Naval Arms Race, 1897-1909.” Diplomacy & Statecraft, Vol. 19 (2008): pp. 712-731.

Holmes, James R. “Why Pearl Harbor is Still Essential.” Retrieved from http://www.dmzHawai’i.org/?tag=alfred-thayer-mahan, 2 April 2014;

Holmes, James R. and Yoshi Yoshihara, “Mahan’s Lingering Ghost.” Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute, Vol. 135, No. 12 (December 2009), pp. 40-45: pp. 40. Accessed 6 November 2013:

Karsten, Peter. “The Nature of ‘Influence’: Roosevelt, Mahan and the Concept of Sea Power.” American Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 4 (Oct. 1971), pp. 585-600.

Lafeber, Walter. “The ‘Lion in the Path’: The U.S. Emergence as a World Power.” Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 101, No. 5, Reflections on Providing for “The Common Defense”, (1986), pp. 705-718.

Lee, Erika. “The Chinese Exclusion Example: Race, Immigration, and American Gatekeeping, 1882-1924.” Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 21, No. 3 (2002), pp. 36-62.

Livermore, Seward W. “The American Navy as a Factor in World Politics, 1902-1913.” The American Historical Review, Vol. 63, No 4 (July 1958), pp. 863-879.

Maurer, John H. “Fuel and the Battle Fleet: Coal, Oil, and American Naval Strategy, 1898-1925.” Naval War College Review, Vol. 34, No. 6, Seq. 288 (Nov.- Dec. 1981), pp. 60-77.

Morris, Edmund. “’A Matter of Extreme Urgency’: Theodore Roosevelt, Wilhelm II, and the Venezuela Crisis of 1902.” Naval War College Review, Vol. 55, No. 2 (Spring 2002), pp. 73-85.

_ _ _ _ _. Theodore Rex. New York: Random House, 2001.

Ricard, Sergé. “Theodore Roosevelt: Imperialist or Global Strategist in the New Expansionist Age?” Diplomacy & Statecraft, Vol. 19 (2008), pp. 639-657.

Still, William N., Jr. American Sea Power in the Old World: The United States Navy in European and Near Eastern Waters, 1865-1917 (Contributions in Military History, Number 24). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1980.

(Return to April 2016 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

- The author would like to thank, in no particular order, Richard Goette, PhD (Adjunct Assistant Professor, Canadian Forces College), Chris Madsen, PhD (Professor, CFC), Sergé Richard, PhD (Professor Emeritus, University of Paris III – Sorbonne Neouvelle), Dave Winkler, PhD (Naval Historical Foundation), Cathy Murphy (Chief Librarian, CFC), Joel J. Sokolsky, PhD (The Royal Military College of Canada), Aldona Sendzikas, PhD (Associate Professor, The University of Western Ontario), and Margaret Kellow, PhD (Associate Professor, UWO) for their aid, and encouragement in the creation of this essay. ↩

- Alfred Thayer Mahan (President, US Naval War College) to the Secretary of the Naval Institute, 27 November, 1888, pp. 6 (Correspondence), The Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan, archived microfilm collection (United States of America Library of Congress), Courtesy of the Canadian Forces College IRC, Toronto, Ontario. ↩

- Extracts of a letter from S.B. Luce to B.F. Tracy (Secretary of the Navy), 14 March 1889, pp. 2 (Correspondence), The Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan. ↩

- While Roosevelt and his supporters appreciated Hawai’i in manners beyond its military value, the bulk of their rhetoric was couched in terms designed to place a legitimate political “spin” on an otherwise military agenda, a conversation too broad in scope for a paper – and presentation – of this size. The annexation of Hawai’i was a component of a far greater political concern in United States domestic policy, sprouting out of economic considerations and, sadly, the last vestiges of North American slavery. These were not concerns for Mahan in his role as a maritime theorist, and so will not be addressed here. Similarly, modern assessments of Hawaiian strategic value will not be addressed, although I will identify some salient strategic and geo-political concerns relevant to this discussion at the end of the essay and presentation. ↩

- Roosevelt would later become Assistant Secretary of the Navy and eventually President of the United States of America. ↩

- This advisory clique includes Henry Cabot Lodge, William Sowden Sims, Bradley Fiske, A.T. Mahan, George Dewey, and William H. Moody, among others. Carl Cavanagh Hodge, “A Whiff of Cordite: Theodore Roosevelt and the Transoceanic Naval Race, 1897-1909,” in Diplomacy and Statecraft, Vol. 19 (2008), pp. 712-731: pp. 720; Edmund Morris, “’A Matter of Extreme Urgency,’” pp. 75-78, 80, 82; John H. Maurer, “Fuel and the Battle Fleet: Coal, Oil, and American Naval Strategy, 1898-1925,” in Naval War College Review, Vol. 34, No. 6, Seq. 288 (Nov.-Dec. 1981), pp. 60-77; Seward W. Livermore, “The American Navy as a Factor in World Politics, 1903-1913,” in The American Historical Review, Vol. 58, No. 4 (July 1958), pp. 863-879: pp. 863, 863n, 873, 875; Elting E. Morison, John M. Blum and John J. Buckley (eds.), The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt: Volume I – The Years of Preparation, 1868-1898. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1951), Theodore Roosevelt to William Sheffield Cowles, 12 December 1901. The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt (Morison, et al.) are indexed according to theme, as indicated in the volume’s subtitle. Each of these collections will be cited according to their collective index. They will therefore appear thus: Letters, Vol. I & II, Letters, Vol. III & IV, Letters, Vol. V & VI, Letters, Vol. VIII. For specific letters from these collections and in Henry Cabot Lodge, Selection from the Correspondence of Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge, 1884-1918, Vols. I-II (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925), I will refer to the specific volume (Selections I, or Selections II in the case of the Lodge collections) and will provide a listing including the author’s initials, a hyphen, and the recipient’s name followed by the date the letter was written; Edward L. Beach, The United States Navy: 200 Years. (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1986), pp. 335, 415; Howard K. Beale, Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of America to World Power (The Albert Shaw Lectures on Diplomatic History, 1953). (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1953), pp. 20, 22; Edmund Morris, Theodore Rex. (New York: Random House, 2001), pp. 180; William N. Still, Jr., American Sea Power in the Old World: The United States Navy in European and Near Eastern Waters, 1865-1917 (Contributions in Military History, Number 24). (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1980), pp. 93-96. ↩

- Mahan to Rear Admiral S.B. Luce (Naval War College), 22 January, 1886, pp. 1 (Correspondence), The Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan; Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future, Kindle eBook, pp. 41 of 318, location 307 of 2371. Please note that as this is an ebook resource, the precise physical location of a given citation may vary from version to version and is largely dependent upon the reading software used. ↩

- Mahan, The Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future, Kindle eBook, pp. 43 of 318, location 322 of 2371; “New American Naval Base at Hawai’i,” The Times (London, England), 24 November 1909 (reprinted Academic OneFile, 24 November 1992, News, pg. 19). Accessed 2 March 2014. (http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA116241233&v=2.1&u=lond95336&it=r&p=AONE&sw=w&asid=676074f6769665453ebbb31eaf782473). ↩

- “New American Naval Base at Hawai’i,” The Times (London, England), 24 November 1909 (reprinted Academic OneFile, 24 November 1992, News, pg. 19). Accessed 2 March 2014. (http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA116241233&v=2.1&u=lond95336&it=r&p=AONE&sw=w&asid=676074f6769665453ebbb31eaf782473); Mahan, The Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future, Kindle eBook, pp. 41 of 318, location 308 of 2371. This chapter, entitled “Hawai’i and Our Future Sea Power”, originally took form as a letter to the editor of Forum in the New York Times, 31 January, 1893, out of which stemmed the larger essay as referenced here. ↩

- http://www.seos-project.eu/modules/oceancurrents/oceancurrents-c02-p03.html. This link is still active as of 15 February, 2015. Caption reads: “Map of the mean surface currents. This is the average pattern. The strength and direction of each current varies with the seasons and from year to year.” ↩

- Atlantic-council.ca/breaking-the-bottleneck-maritime-terrorism-and-economic-choke-points-part-1. This page was accessed March 2014; it has since been removed. ↩

- Mahan, The Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future, Kindle eBook, pp. 38 of 318, location 235 of 2371, pp. 52 of 318, location 393 of 2371; Wallace Rice, “Some Current Fallacies of Captain Mahan,” in The Dial: A Semi-Monthly Journal of Literary Criticism, Discussion, and Information (1880-1929), Vol. 330 (16 March, 1900), pp. 198; Admiral C.S. Sperry to the Secretary of the Navy, 27 January 1908, pp. 4 (Theodore Roosevelt Correspondence, 1890-1910), The Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan; Alfred Thayer Mahan to Col. Sterling, 23 December 1898, pp. 1 (Theodore Roosevelt Correspondence), The Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan; William R. Braisted, “The Philippine Naval Base Problem, 1898-1909,” in The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 41, No. 1 (June 1954), pp. 21-40: pp. 22; Michael T. Corgan, “Review Article: Mahan and Theodore Roosevelt – The Assessment of Influence,” Naval War College Review, Vol. 33, No. 6 (Nov.-Dec. 1980), pp. 89-97: pp. 95; Hodge, pp. 720. ↩

- Mahan, The Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future, Kindle eBook, pp. 45 of 318, location 336 of 2371. ↩

- Mahan to Admiral Sir B.F. Clarke, 24 May 1898, pg. 1 (Correspondence, 1908-1910), The Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan; Walter Lafeber, “The ‘Lion in the Path’: The U.S. Emergence as a World Power,” Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 101, No. 5, Reflections on Providing for “The Common Defense” (1986), pp. 705-718: pp. 707-708, 717-718. ↩

- Senator George Clement Perkins to Rear Admiral A.T. Mahan, 7 January 1911, pp. 1 (Correspondence, 1908-1910), The Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan. There is another signature on the letter, but the author could not identify its owner, pp. 2; Mahan to Theodore Roosevelt 27 December 1904, pp. 2 (Theodore Roosevelt Correspondence 1890-1915), The Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan. ↩

- Robert Stein, “The Defense of Alaska,” pp. 2, in Robert Stein to Alfred Thayer Mahan 25 March 1910, (Correspondence 1908-1910), The Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan. Stein’s argument is treated here as the most effective substantive counter to Mahanian analysis with regard to the military-strategic value of the Hawaiian archipelago to the United States. ↩

- Ibidem. ↩

- Ibid. Stein’s document addresses not only the strategic value of Alaska contra that of Hawai’i, but also the danger a foreign-occupied (i.e., a non-American) Alaska posed to Canada, as well as a proposed argument in favour of the construction of a complex railroad chain as part and parcel of the Monroe Doctrine. Curiously, Stein forwards the argument that the construction of a railway connecting the contiguous United States with Alaska would in fact pacify the Canadians and make them more likely to formally accept the Monroe Doctrine as a component of international law; pp. 5-6. Stein’s argument likely refers to the inhabitants of what is now British Columbia, as Canadian affairs were being directed by London (England), not Ottawa – see commentaries on the Alaskan Boundary Dispute (resolved in 1903) for more information. He also makes a huge leap in his contention that the Monroe Doctrine was internationally accepted: it was a posture of the United States to defend itself against belligerent European nations in areas claimed by the United States as being vital to its military defence and/or its economic security. Stein’s argument, therefore, is heavily couched in American exceptionalist rhetoric. ↩

- With thanks to Professor Margaret Kellow, PhD (University of Western Ontario) for these observations. ↩

- Alfred Thayer Mahan (Research Notes File, Miscellaneous Drafts and Notes 1904 – [ca. 1914, and undated ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Mahan, The Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future, Kindle eBook, pp. 47 of 318, location 350 of 2371. ↩

- Ibid., pp. 49 of 318, location 365 of 2371. ↩

- Edward S. Ellis, A. M., Ellis’ History of the United States from the Discovery of America to the Present Time, (Minneapolis, MN: Western Book Syndicate, 1899). Downloaded from Maps ETC on the Web at http://etc.usf.edu/maps (map #02949). ↩

- Maurer, pp. 63-64, 63n16, 69, 75. Maurer draws attention to a report by Mahan authored 15-20 August 1898 discussing the deportment of forward bases; Alfred Thayer Mahan to Secretary of the Navy, 21 April 1911, in Robert Seager and Doris D. Maguire (eds.), Letters and Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan, Vol. 3, (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1975), pp. 399. ↩

- Peter Karsten, “The Nature of ‘Influence’: Roosevelt, Mahan and the Concept of Sea Power,” in American Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 4 (Oct. 1971), pp. 585-600. ↩

- Ibid., pp. 593n26. ↩

- Ibid., pp. 591, 596, 598, 593n26; Paolo E. Coletta, Untitled Review of Richard W. Turk, The Ambiguous Relationship: Theodore Roosevelt and Alfred Thayer Mahan, in American Historical Review, Vol. 93, No. 5 (Dec. 1988), pp. 1413-1414: pp. 1413; Corgan, 89-97. Corgan’s entire review addresses this issue, and is just as convincing as Karsten’s argument; Hodge, 713, 715-717. ↩

- Mahan, The Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future, Kindle eBook, pp. 50 of 318, location 379 of 2371. ↩

- Reproduction of Chart Showing Position of UNALASKA. Robert Stein to A.T. Mahan, 25 March 1910, The Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan, Correspondence 1908-1910, CFC-IRC. ↩

- James Holmes, “Why Pearl Harbor is Still Essential,” retrieved from http://www.dmzHawai’i.org/?tag=alfred-thayer-mahan, 2 April 2014; See also James R. Holmes and Yoshi Yoshihara, “Mahan’s Lingering Ghost,” in Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute, Vol. 135, No. 12 (December 2009), pp. 40-45: pp. 40. Accessed 6 November 2013: search.proquest.com/docview/205990005/1419454E66C116CEABE/11?accountid=15115; The author would like to thank Professor Holmes (US Naval War College) for his guidance in researching this aspect of this paper. Personal Correspondence with James R. Holmes (E-Mail), 2 April 2014. ↩

- Approximately $23 million in 2014 dollars; http://www.davemanuel.com/inflation-calculator.php . ↩

- Braisted, pp. 38. ↩

- Selections, Vol. 1, TR–HCL, 27 October 1894, pp. 139; Corgan, pp. 95; Neil Bernard Dukas, A Military History of Sovereign Hawai’i. (Honolulu, HI: Mutual Publishing, 2004), pp. 172-175. ↩

- Mahan, The Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future, Kindle eBook. ↩

- Clement was a San Francisco lawyer who had testified in the 1876 hearings, identifying what he determined to be the need to halt Chinese immigration – and the containment of those of Chinese descent living on United States soil – as part of a rising American gatekeeping ideology. ↩

- Erika Lee, “The Chinese Exclusion Example: Race, Immigration, and American Gatekeeping, 1882-1924,” Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 21, No. 3 (2002), pp. 36-62: pp. 38-39. The author would like to thank Professor Kellow for bringing this source to his attention. As pertinent as racism is to the American imperial experience, it is only glancingly relevant to this essay. Neil Bernard Dukas’ A Military History of Sovereign Hawai’i. (Honolulu, HI: Mutual Publishing, 2004) is an excellent resource for further details. ↩

- Selections, Vol. 1, HCL-TR, 2 December 1896, pp. 240; Julius W. Pratt as quoted in Joseph A. Fry, “Feature Review: The Architects of the ‘Large Policy’ Plus Two,” in Diplomatic History, Vol. 29, No. 1 (January 2005), pp. 185-188: pp. 185. Fry’s review is of Warren Zimmerman’s First Great Triumph: How Five Americans Made Their Country a World Power. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002). ↩

- Selections, Vol. 1, HCL-TR, 2 December 1896, pp. 240; TR-HCL 4 December 1896, pp. 243; TR-HCL, 6 April 1897, pp. 266; TR-HCL, 8 April 1897, pp. 266; TR-HCL 10 July 1898, pp. 323; Fry, pp. 186-187. ↩

- Selections, Vol. 1, TR-HCL, 17 June 1897, pp. 267. ↩

- Selections, Vol. 1, TR-HCL, 3 August 1897, pp. 168. ↩

- Selections, Vol. 1, HCL-TR, 19 August 1897, pp. 273; HCL-TR, 29 June 1898, pp. 317. ↩

- Selections, Vol. 1, HCL-TR, 31 May 1898, pp. 302; TR-HCL & J.S. Morgan & Co., 10 August 1899, pp. 416; Selections, Vol. 2, HCL-TR, 11 January 1916, pp. 470; HCL-TR, 1 February 1916, pp. 474-476; TR-HCL, 4 February 1916, pp. 477; HCL-TR, 9 February 1916, pp. 482-484; Lafeber, 712-713. ↩

- Wallace Rice, “Some Current Fallacies of Captain Mahan,” in The Dial: A Semi-Monthly Journal of Literary Criticism, Discussion, and Information (1880-1929), Vol. 330 (16 March, 1900), pp. 198. Rice accuses Mahan of being more interested in creating reasons for his countrymen to die than in promoting peace; Mahan, The Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future, Kindle eBook, pp. 38 of 318, location 235 of 2371; Mahan to Theodore Roosevelt 27 December 1904, pp. 2 (Theodore Roosevelt Correspondence 1890-1915), The Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan. ↩

- Lafeber, 714. Both Clement and Rice were isolationists, and, as has been illustrated, were quite racist. ↩

- Selections, Vol. 1, TR-HCL, 12 June 1898, pp. 309; Wendell D. Garrett, “John Davis Long, Secretary of the Navy, 1897-1902: A Study in Changing Political Alignments,” in The New England Quarterly, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Sept. 1958), pp. 291-311: pp. 300. ↩

- Selections, Vol. 1, HCL-TR, 15 June 1898, pp. 311; HCL-TR, 24 June 1898, pp. 313; HCL-TR, 4 July 1898, pp. 318; HCL-TR, 6 July 1898, pp. 321; HCL-TR 23 July 1898, pp. 330. ↩

- Theodore Roosevelt to A.T. Mahan, 8 June 1911, pp. 2, (Theodore Roosevelt Correspondence 1890-1915), The Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan, archived microfilm collection (United States of America Library of Congress), courtesy of the Canadian Forces College IRC, Toronto, Ontario. Dukas relates a series of discussions between Queen Lili’uokaliani and President Harrison, and a statement of Grover Cleveland that progress along similar lines of thought. The gist, however, was to suggest that the queen had demonstrated an inability to resolve her own domestic issues and that United States interests were served by overthrowing the revolutionaries rising against her, even though the United States’ intervention was “… an unauthorized act of war …. Stevens’ proclamation establishing a United States protectorate over Hawai’i was subsequently ‘disavowed’ by Washington and he was reprimanded for having taken an active part in the de facto government of Hawai’i.” Dukas, 178. ↩

- Wendell D. Garrett, “John Davis Long, Secretary of the Navy, 1897-1902: A Study in Changing Political Alignments,” in The New England Quarterly, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Sept. 1958), pp. 291-311: pp. 298; Serge Ricard, “Theodore Roosevelt: Imperialist or Global Strategist in the New Expansionist Age?” Diplomacy & Statecraft, Vol. 19 (2008), pp. 639-657: pp. 641. The author would like to thank Professor Ricard, Professor Emeritus at the University of Paris, Sorbonne Nouvelle and the Observatory of American Foreign Policy, and a noted Theodore Roosevelt scholar, for his insights into this discussion. Personal Correspondence, Serge Ricard (E-Mail), 9 April 2014. ↩

- “Annexation of Hawai’i”, in Maine Farmer (1844-1900), 24 June 1897, Vol. 65, No. 34, American Periodicals, pp. 4. ↩

- “Annexation,” pp. 4. ↩

- “Annexation,” pp. 4; See also Erika Lee, “The Chinese Exclusion Example: Race, Immigration, and American Gatekeeping, 1882-1924,” Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 21, No. 3 (2002), pp. 36-62. ↩

- “Annexation,” pp. 4. ↩

- Longman Gorman, “The Administration and Hawaii,” The Northern American Review (1821-1940), Vol. 165, No. 490, American Periodicals, pp. 379. ↩

- Gorman, 379. ↩

2 Responses to Alfred and Theodore Go to Hawai’i: The Value of Hawai’i in the Maritime Strategic Thought of Alfred Thayer Mahan