Contents:

Background on the Situation

Courses of Action Taken

Analysis of Results and Consequences

Bibliography

Timothy A. Walton

Independent Scholar

In his declaration of war, President Woodrow Wilson protested: “German submarine warfare against commerce is a warfare against mankind.” 1 Following the defeat of the Central Powers in World War I, the international community adopted the 1930 and 1936 London Naval Treaties, which declared “cruiser rules” applied to submarines as well as merchant vessels. 2 Nonetheless, during the Spanish Civil War and to a much greater extent World War II, the scourge of the submarine would strike again. German submarine effectiveness in targeting merchant shipping led to major Allied innovations in technology, tactics, and methods. These in turn were met by reciprocal German responses.

This paper will analyze the use of operational research methods in World War II by Britain’s Coastal Command in aerial counter-U-Boat operations. 3 It contends that operational research methods significantly improved Coastal Command’s operational effectiveness and led to changes in Allied policies and procedures at the tactical, operational, and strategic levels. The paper will proceed in three sections: background, courses of action taken, and analysis of results and consequences.

In order to frame the scope of effort, the paper focuses on Coastal Command’s efforts in the Atlantic, while noting significant initiatives in the Mediterranean and Indo-Pacific theaters. Additionally, in focusing on British operational research, it seeks to complement scholarship on American counter-U-boat operational research activities, as documented by scholars such as Max Schoenfeld and General Montgomery Meigs. 4 Lastly, in assessing the effectiveness of operational research methods in improving counter-U-boat performance, the paper will limit its discussion of the enormous role of signals intelligence (namely, intelligence gained from “Ultra”, the decryption of the German Enigma code machine) in shaping operational search patterns. While not comprehensive, this piece aims to analyze this crucial analytical method in order to understand the historical lessons more perfectly, and where appropriate draw other historical and contemporary implications. 5

Background on the Situation

During World War I, naval actions were concentrated in the Atlantic and Mediterranean. After the declaration of war, Allied Forces, led by Great Britain, began a distant naval blockade of Central Power ports. Over time the blockade had a major impact on the ability of the Central Powers to import food and supplies. 6 In response, in 1914 Germany designated the waters around the British Isles a “war zone” in which all belligerent ships (including merchants) were subject to destruction without warning. 7 Apart from select, high-profile successes early in the war, German U-boats were primarily employed against merchants. 7

In addition to the development of technological countermeasures such as anti-submarine warfare hydrophones, depth charges, mines, and aircraft, Great Britain in September 1917 began full-scale convoying. 9 These tactics and technologies accelerated the German culmination point that was likely reached in July of 1917. Additionally, while a reciprocal dynamic developed, the German navy (in part limited by the technological capabilities of the submarines) did not develop effective tactics to counter the convoying, such as wolf packs. By 1918, Allied losses had reached non-critical levels while major German submarine losses slashed force structure and morale, relegating the force to coastal defense.

At the end of the Great War, German leaders concluded the failure of unrestricted submarine warfare principally lay not in faulty assessments of enemy economic output or performance, but in a small force structure. With only twenty to thirty 500 to 700 ton U-boats on station around the British Isles, one of German Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff’s experts, Dr. Richard Fuss, conceded: “The U-war was never unrestricted.” 10

During the Interwar Period, Germany secretly reconstituted its submarine force. In 1936, during the Spanish Civil War Germany’s 2nd U-Flotilla, named “Saltzwedel”, began an active, though covert, role complementing the efforts of their Italian comrades against the Republican forces. In the Spanish Civil War, active sonar (then referred to by the British as ASDIC) was first used by British warships to pursue German and Italian submarines. 11 By the terms of the Nyon Arrangement, British warships were empowered to depth charge submarine contacts which displayed hostile intent. 12

The first official meeting of the National Defense Research Committee. Source: Vannevar Bush, “National Defense Research Committee,” The Scientific Monthly, Vol. 51, No. 3. (Sep., 1940), pp. 284-285, on 284.

Despite the great advances that took place in Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) between 1914-1918 and the operational experimentation of the Spanish Civil War, many of the tactical and operational lessons of World War I were forgotten during the Interwar Period. 13 Additionally, British and American military leaders displayed overconfidence in their ASW capabilities. In June 1935, after the Anglo-German Naval Agreement (that codified the end of Germany’s abiding by the military clauses of the Treaty of Versailles) Admiral Chatfield, the First Sea Lord wrote “our methods [of ASW] are now so efficient that we will need fewer destroyers in the North Sea and the Mediterranean.” 14

In response to these attitudes and the growing possibility of war, concerned scientists in the U.S. and Great Britain offered their technical skills to prepare for the potential war to come. In the United States, Vannevar Bush, President of the Carnegie Institute, formed the National Defense Research Committee in June 1940. 15 Securing funds from President Roosevelt’s budget, Bush and his colleagues arranged for a committee sponsored by the National Academy of Science to study subsurface warfare. The Colpitts Report, named after the committee’s chairman, incisively criticized the scientific background of the U.S. Navy’s antisubmarine warfare effort, noting: “We feel an altogether inadequate research effort on fundamentals has been put forth since the last war.” Colpitts noted as well that the scientific contribution to antisubmarine warfare was, “also a question of tactics and tactical doctrine, of personnel and training and of operational records.” 15 Similar observations were made by concerned scientists in Great Britain.

Establishment and Aims of the ORS Office

The Royal Air Force’s (RAF) Coastal Command was one of three branches of the Service, the other two being RAF Fighter Command and RAF Bomber Command. Its primary task was to protect British shipping from enemy naval threats, with strike of enemy naval forces as a secondary duty. However, Great Britain entered World War II unprepared for ASW. Coastal Command “began the war with unsuitable aircraft for hunting U-boats, no airborne depth charges, and aircrews untrained in anti-U-boat operations.” 17 The German navy also entered into the war with an inadequate submarine force structure. At the outbreak of war, it only had 26 ocean-going U-boats. 18 German Befehshaber der Unteresebooten (BdU) (Commander in Chief, submarines) Admiral Karl Dönitz estimated he “needed 300 U-boats to defeat the Allied convoys and force Britain into submission.” Nonetheless, the German Navy initially achieved great success.

In response to the German threat, the British military sought improved means to counter the serious U-boat threat. After some lag and resistance, in late 1941 an Operational Research Centre was formally established at the Air Ministry in order to improve operational analysis. 19 Simply defined, operations research is “a scientific method of providing executive departments with a quantitative basis for decisions regarding the operations under their control.” 20 A subsidiary Operational Research Section (ORS) was established in RAF Coastal Command, and equivalent organizations were established in Canada and the U.S.

Conrad Hal Waddington, one of the leaders of Coastal Command’s ORS (thereafter referred to as ORS) and its post-war historian, recounted that ORS sought to define problems (using data to inquire what the problem is), attack the problem using various methods, and produce reports with actionable recommendations. 21 Initially ORS allocated individuals to projects on an as-available basis; in mid-1943, however, ORS was divided into four groups (with approximately four individuals in each group): Anti-U-Boat operations, Anti-Shipping operations, Planned Flying and Maintenance, and Weather and Navigation.

Courses of Action Taken

This section will analyze the courses of action taken by Coastal Command ORS to counter the U-boat threat. It will proceed by examining principles of aircraft-submarine warfare, the progress of the campaign, and specific initiatives that highlight ORS’ contribution to improving Coastal Command combat effectiveness.

Principles of Aircraft-Submarine Warfare

Throughout most of the war, standard German U-boats were compelled to spend a large portion of their time surfaced in order to recharge their batteries and navigate at greater speeds. “The 500 ton U-boat had an overall endurance on the surface ranging from 14,000 miles at 6 knots to 2,800 at 17 knots; but the underwater endurance on one charge of the batteries was only about 14 miles at 8 knots, 28 miles at 6 knots, 65 miles at 4 knots.” 22

Additionally, U-boats also found it necessary to spend a considerable amount of time on the surface in their attacks on convoys. Usual convoy speeds across the Atlantic were 7 or 9 knots. Therefore, U-boats generally required surface navigation in order to shadow or gain a bearing on convoys. The introduction of the snorkel to a select number of U-boats in late 1944 provided U-boat’s the ability to run diesel engines and recharge batteries while still submerged.

U-boat operations chiefly consisted of two tactics: solitary stalking in littoral waters or wolf-pack tactics in the open ocean. The former relied on submerging by day and surface recharging of batteries at night. This tactic initially worked as Coastal Command lacked effective night capabilities. In contrast wolf-packs essentially used submarines as surfaced torpedo boats at night. Patrol lines of submarines, guided by BdU, would seek to find convoy targets. The coordination of a large pack attack usually took 20 or more hours to develop.

Progress of the Campaign

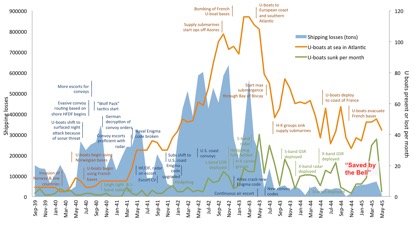

The U-boat/counter-U-boat campaign in the Atlantic proceeded throughout the entirety of the war. It shifted in character and geographic location as German forces made operational and tactical adjustments, and Allied forces followed suit. Early in the war, German U-boats conducted independent actions in coastal waters. Improvements in British ship-borne active sonar and the harassing presence of aircraft led Admiral Dönitz to command wolf-pack tactics in the mid-Atlantic. During this period, the average number of U-boats at sea was about 25. 23 In 1941 1,976,000 tons were sunk for a loss of about 36 U-boats. These results were better than those of 1939 and 1940. Nonetheless, aircraft was beginning to influence German U-boat morale and patrol tactics. In response to the air threat, Admiral Dönitz placed his patrol lines as far as possible in the mid-Atlantic outside the reach of air cover. 24

Shipping Losses During the Battle of the Atlantic

Source: John Stillion and Bryan Clark. “What it Takes to Win: Succeeding in 21st Century Battle Network Competitions”, Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2015, 28.

With the entry of the United States into the war, Admiral Dönitz directed his forces to conduct inshore operations off the U.S. coast (Operation Paukenschlag, “Drumroll”), taking full advantage of the lack of U.S. preparation. 27 German submarines had great success in U.S. coastal waters until June 1942, when the U.S. fully adopted convoy tactics and fully organized an effective anti-submarine air force. The introduction of new 1,600-ton supply submarines, to complement surface tankers, combined with the increasing monthly production of Mark VII and Mark IX U-boats promised to give BdU greater numbers of submarines in the patrolling areas. 28

Additionally, in early 1942, Germany broke British Naval Cipher Number 3, the Allied convoy code. By July 1942, the Germans read 80 percent of all messages sent in this cipher. 29 This reinforced the highly centralized command and control of the U-boat force, which was successful initially but provided weaknesses that could be exploited by the Allies. With exception to most of 1942 and brief periods in 1943, Allied intelligence was able to decipher most German Enigma radio transmissions. 30

In August 1942, German forces again conducted wolf-pack tactics against convoys in the mid-Atlantic. During this time, German forces reached a culmination point in March 1943 (sinking 108 Allied ships at a cost of only 14 U-boats lost). However, due to mounting losses caused by the increasing effects of land-based and escort carrier air power and the increase in naval escorts (formed in hunter-killer groups), German forces withdrew from the Atlantic offensive in May 1943. 31

Subsequently, they focused on various, distant vulnerable points, principally in the Caribbean targeting the transport of petroleum and other raw materials. As Admiral Dönitz’s War Diary states on 15 April 1942: “The enemy powers’ shipping is one large whole. It is therefore immaterial where a ship is sunk…. Tonnage must be taken where it can be destroyed most reasonably as afar as making full use of the boats is concerned.” 32 This geographic shifting of areas of operation in order to achieve tonnage goals and minimize danger is logical; however, it retarded fundamental assessments of tactics and technological countermeasures. Admiral Dönitz “did not look to scientists and engineers for ways to improve capabilities of submarines until the summer of 1943, when the slide toward defeat had become obvious.” 33

In October 1943, a second, disastrous attempt was made to return to the North Atlantic. This offensive sought to make improved use of German Ju. 290 aircraft for reconnaissance purposes. However, cooperation between aircraft and the submarines was difficult due to problems with navigation coordination, communications, and the low mobility of submarines. The invasion of Europe in June 1944 prompted an unsuccessful U-boat counter attack. By this time, increasing numbers of snorkel-fitted boats were fielded. These performed much better in coastal waters and were significantly less vulnerable to aircraft; however, they could still be tracked with active sonar and attacked by surface ships with new, forward-launched weapons such as Mousetrap and Hedgehog.

ORS Initiatives

ORS initiatives significantly improved the combat effectiveness of Coastal Command operations against U-boats. Their efforts can be grouped into five categories: organization of effort, improvement of radar performance, addressing visual problems, tactical strike, and operational-level analysis.

The Organization of Effort

ORS took a comprehensive, system-level approach to improving Coastal Command effectiveness. This began with addressing basic questions and problems with the organization of effort within the force. One of the main contributions of ORS in this regard was to thoroughly systematize and improve Coastal Command readiness rates and operational availability. It did so through a process of “Planned Flying and Planned Maintenance”, which systematically analyzed the inputs required to generate combat power. 34

ORS also examined questions of navigation. While seemingly trivial, aircraft search patterns for convoys had resulted in them not meeting convoys nearly 80% of the time for distant convoys in 1941. ORS analysis introduced more effective search patterns and promoted the introduction and proper use of different, neglected navigational aids. 35

As a related issue, ORS analyzed the impact of weather on operations and the optimization of flying time. This led to changes in maintenance patterns as well as an analysis of the adequacy of bases. For instance, toward the end of 1944, after the Germans had lost their Biscay Bay U-boat bases, it was recognized that considerable U-boat traffic would be sent northwards round the Iceland-Faroes Channel. Recognizing the limiting weather conditions, ORS concluded that while the expansion of certain bases in Scotland and Iceland was appropriate, others in the area were paradoxically not, even though they were closer to the operating area. This was because poor weather conditions would provide an even lower sortie rate than aircraft flying from further away. 36 These analyses improved the efficiency and effectiveness of the force.

Radar (ASV)

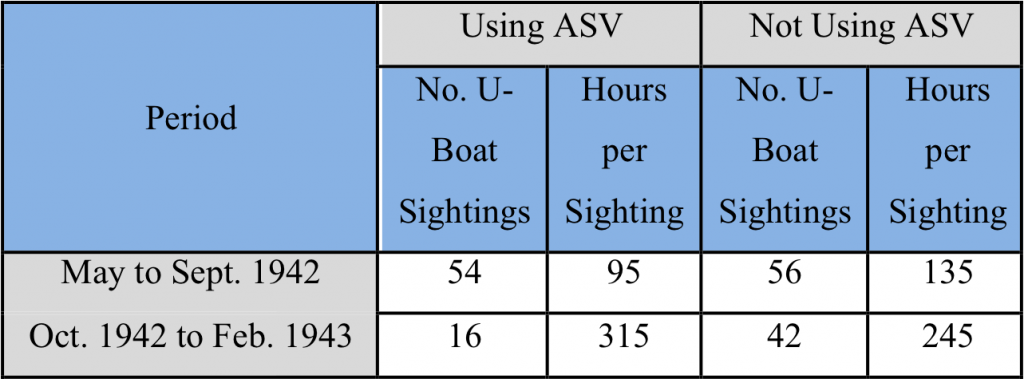

In its anti-U-boat form, radar was known as Anti-Surface Vessel (ASV). 37 The war in the Atlantic exhibited a reciprocal dynamic as Allied forces adopted L, S, and X band radars, and German forces introduced appropriate countermeasures. ORS strongly contributed to analyses of the effectiveness of different radars, development of search patterns and tracks, and the lessening of incident radar energy needed to detect and approach submarines. 38 ORS also influenced radar operator training. By comparing the quality of radar operators, it introduced a process for eliminating inferior operators via tests during the training process. This was recommended after discovering that the bottom 15% of classes of radar operators never detected a U-boat. 37

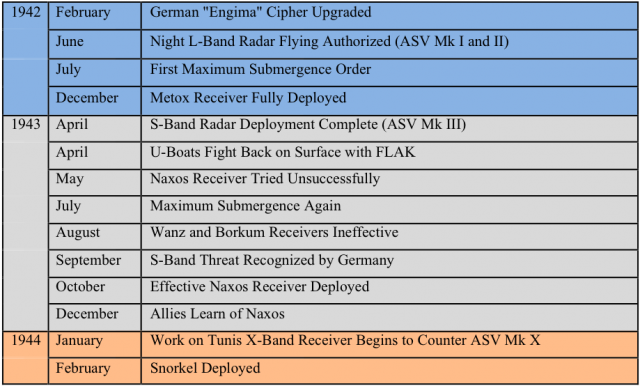

Furthermore, ORS strongly shaped analysis of operational performance in order to determine reciprocal responses by German forces and recommend actions on appropriate countermeasures. For example, as early as 1941, questions were being asked as to the cause of disappearing contacts with Mk. II ASV. Through ORS analysis, coupled with intelligence information, it was deduced by autumn of 1942 that U-boats had been fitted with a receiver to counter ASV Mk. II. 40 As Figure 1 shows, the use of daytime ASV Mk II was paradoxically to the disadvantage of Allied forces, because of German receivers. 41 With the introduction of ASV Mk III, Allied radar advantage was once more regained, to be countered again by the Germans. Winter 1943-1944, the Germans launched radar balloon decoys termed Aphrodite; however, they were designed for 1.5 meter wavelengths, instead of the centimeter ASV Mk. IIIs. 42

Figure 1: Reciprocal Reponses in the Radar War 43

In May 1941, ORS conducted an analysis of visual problems related to aircraft spotting the U-boat and remaining unseen until near enough to deliver an attack. 44 Analyzing available data, it found that “in nearly 40% of the cases, the U-boat was already diving when first seen, which meant that it had seen the aircraft first. In a further 20%, the U-boat had already submerged (having only its periscope visible).” Therefore, around 60% of U-boats had spotted aircraft first—not counting U-boats that had completely submerged and were never spotted. 45 At the time, aircraft in use were painted with the standard Bomber Command black, which was intended to defeat searchlights. ORS recommended painting the bottom and sides of Coastal Command aircraft with white camouflage. The recommendation improved unsubmerged detection rates by 20%. 46 A commensurate factor noted in ORS analysis is that the deterioration in the standard of training of U-boat crews may have also contributed to the increased success.

Figure 2: Analysis of Day Sightings 47

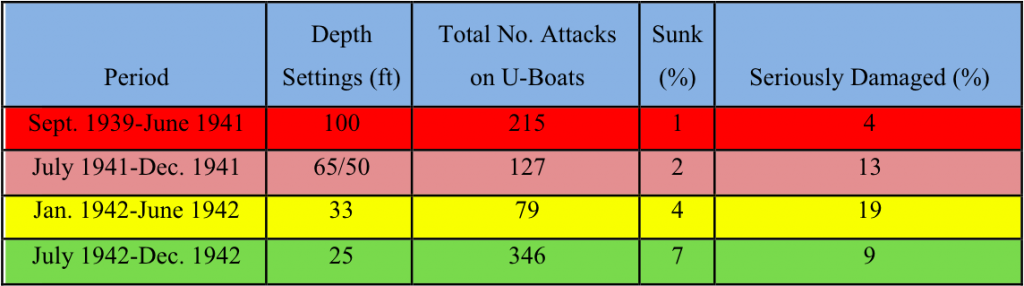

The culmination of 55,000 man-hours or more of pilots, maintenance staff, and other ground personnel and all the aforementioned factors was the opportunity to conduct a brief attack on a U-boat. Frustratingly, though, aircraft lethality against visible U-boats was quite low at the start of the war. With the help of ORS, the lethality per attack on a visible U-boat rose from 2 or 3% in 1941 to about 40% in 1944, and to as high as 60% on the few surfaced U-boats seen in the last months of the war. 48 ORS’ main contributions were to the selection and arming of weapons and their aiming. Throughout the war, the main weapon employed by aircraft against the U-boat was the depth-charge, usually fused with a hydrostatic or time delay fuse so as to explode without the necessity of contact with the U-boat. 49 Depth charges are normally dropped in sticks, each stick consisting of a number of depth charges which fall in a more or less straight line along the direction of flight of the aircraft.

Through their analysis, ORS found that depth charges were fused for hydrostatic initiation at 100 feet or 150 feet. This was done with the expectation that submarines would already be at depth when the attack took place; instead, “as many as about 40% of all attacks the U-boat was either visible at the instant of attack or had been out of sight for less than a quarter of a minute.” 50 With only a lethal radius of 15-20 feet in the 250 lb depth charge, depth settings of 100 or 150 feet were way too deep for surfaced or near-surface U-boats. ORS recommended improved fillings for depth charges to increase their lethal radius and recommended depth settings at 25 feet. In a long, evidentiary process convinced the Air Staff to gradually increase the depth settings. 51 These changes were accompanied by increases in the lethality of attack.

Figure 3: Progress of Lethality of Depth Charge Attacks 52

ORS also provided the data to shape tactics. For example, in April 1943, U-boats adopted the practice of staying on the surface and fighting back with their anti-aircraft armament. In June and July of 1943, U-boats transiting the Bay of Biscay proceeded in daylight in groups of 3 to 5 to have supporting fire. Approximately 50% of the aircraft attacking through flak were hit, and in July and August when the fire was heaviest from U-boat packs, about 11% of attacking aircraft were shot down. 54 ORS provided Air Staff with the analysis to show that thanks to the valor of the aircrews, German forces were losing submarines at a disproportionate ratio that greatly favored the Allies. Coastal Command thus continued with its low-altitude attacks, instead of adopting medium-altitude bombing. The loss of 45 U-boats and serious damage of more during this period broke the force of the standard U-boat during the summer of 1943 and led to a policy of maximum submergence at the expense of much longer transit time. 42

Operational-Level Analysis

ORS analysis assisted officers in developing operations. Against U-boats, Coastal Command primarily conducted two types of operations: the protection of a given convoy and the general protection of shipping by cutting down the U-boats’ mobility, by harassing them, or by sinking them at sea. ORS found that a more economical and effective use of Coastal Command aircraft was instead of providing every convoy with air escort sufficient to prevent a U-boat attack, to focus on threatened convoys. The use of signals intelligence made this possible with a reliability of about 90%. 56 Therefore, wolf-packs could be countered in a cheaper way (than total coverage) by interfering with the shadowing of the convoy and accumulation of the pack.

ORS played a vital role in providing the analysis necessary to support “Transit Offensives” in the Bay of Biscay and elsewhere. Until the capture of the French coastal ports by the Allies in 1944, German U-boats primarily operated from the Bay of Biscay. The northern route from Germany or Norway round the north of Scotland was primarily used by new submarines. The Strait of Gibraltar was also used by submarines entering into the Mediterranean theater and small, pre-fabricated Type XXIII boats that were assembled in Toulon. The limited number of submarines operating in that area and the poor flying conditions and visibility at far northern latitudes made focus on the Bay of Biscay a top priority. By dedicating aircraft to this mission, instead of convoy protection, Coastal Command followed through with the axiom that “offense is the best defense.”

Before the Bay Offensive, though, Sir Archibald Sinclaire, the secretary of state for air, demurred allocating the requested 55 bombers. 57 He noted this could be done only by sacrificing the bombing of Germany, which had been promised to Stalin. Additionally, he expected German fighter cover for their submarines to effectively counter Coastal Command aircraft. This resistance was overcome by ORS analysis, which demonstrated that although the Bay Offensive would not produce an “unclimbable fence”, 58 it would destroy 20-25% of all U-boats that left Biscay ports. 59 In this manner, ORS managed to shift the strategic allocation of resources. Sinclaire’s fears did not come to fruition as Dönitz was unable to obtain sufficient Luftwaffe support to contest the airspace over the Bay of Biscay.

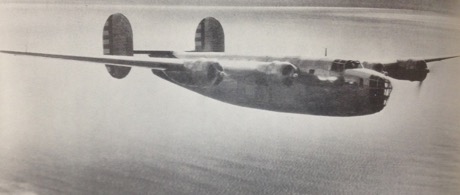

Figure 4: U518 under attack by an RAF Sunderland while outbound north of the Spanish coast, 27 June 1943. 60

Figure 5: The Consolidated B-24 (Liberator) bomber rated as a true Very Long Range aircraft, which was successfully employed by Coastal Command in 1943 to close the Atlantic Air Gap. 61

Analysis of Results and Consequences

In a public speech, Admiral Dönitz once remarked that “the U-boat has no more to fear from aircraft than a mole from a crow.” 63 While the boast was largely true against submerged submarines, it certainly did not apply to U-boats on the surface. During World War II, 289 German U-Boats (of the 1,150 commissioned) were sunk by aircraft. 64 This amounted to approximately 36% of German losses. 65 ORS played a pivotal role in improving the effectiveness of Coastal Command aircraft by shaping technologies, tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP), and operational concepts. While other factors also played an important, if not decisive, role in the defeat of the German U-boat force, ORS sharped Coastal Command’s effort and contributed significantly.

Although this analysis focuses on understanding the historical campaign, there are contemporary lessons to draw from ORS. Chief among them is the value of incorporating operational research expertise into senior levels of decision-making. By ensuring operational research expertise at high levels of the executive decision-making process, one can ensure that operational research skills can actually inform and shape choices, rather than simply providing justification for the established course of action. Executives sometimes say scientists “should be on tap, but not on top.” 66 As stated by Conrad Hal Waddington: “This is a poor way to see the situation as scientists should be in neither of those positions, they should be members of a team, entitled to that degree of respect which they can earn with the practical effectiveness of their advice.” 66

The recruitment of highly skilled talent within such organization is another laudable goal. Although the existential crisis of World War II and the commensurate pull of talent is generally not replicable, standards should be set high. ORS remained fairly small throughout the war, with an average strength of about 16 officer-grade staff and two or three assistants. 68 As an indication of the intellectual caliber of the staff, two of them later received the Nobel Prize and six were Fellows of the Royal Society and National Academy of Sciences. 69

Another lesson to draw from ORS is the value of assigning adequate staff to do the work involved. Senior scientists must have enough time to cogitate creative approaches and experiment with different methodologies. ORS also did not commit itself to any special expertise, such as Queuing Theory, Games Theory, or Decision Theory; instead they were “ready to stick our noses into what everyone told them did not concern them, and to follow wherever that led.” 69 This approach facilitated a comprehensive, or systems-level, approach to analyzing the problem. ORS staff “refused to confine themselves narrowly to what they disdained as ‘gadgetry.’ They insisted on applying scientific method to the whole problem of the detection and destruction of submarines and to the environment in which the submarine operated.” 71 In order to preserve the time of the skilled scientists, routine statistical work was delegated to a Statistical Bureau. 72 Overall, ORS highlights the effectiveness of small, skilled, and empowered groups within staffs.

Operational level expertise should be closely integrated with the senior levels of the command, not only in systems analysis of acquisition programs and the like but actual operations. As stated by Conrad Hal Waddington: “There is a strong general case for moving many of the best scientists from the technical establishments to the operational Commands, at any rate for a time. If, and when, they return to technical work, they will be often much more useful by reason of their new knowledge of real operational needs.” 73

Moreover, their expertise will assist in shaping the operational level of war at sea. During World War II, ORS analysis assisted in defining the specific value of potential operational and campaign-level actions. The U.S. Navy has historically neglected operational-level planning, only adopting the operational-level of war at sea when Admiral Kelso, as Chief of Naval Operations, and General Mundy, Commandant of the Marine Corps, signed the first “naval doctrine publication,” entitled Naval Warfare, in the spring of 1994. 74 The three elements of war, in the Navy’s eyes, had previously been strategy, tactics, and logistics. The work of ORS reinforces the value in shifting the paradigm of ASW strategy, and naval strategy more broadly, from one based on the positional employment of forces to one that focuses on both the systemic analysis of inputs required to affect the enemy (a WW II predecessor to effects/kill chain analysis) as well as the operational level definition of goals and aims. 75

The experience of ORS also provides lessons on the iterative and reciprocal nature of war. Enemy activity is dynamic, constantly changing in its technology, tactics, and geographic areas. For every counter developed, planners must expect a reciprocal response and develop institutions capable of rapidly innovating. Thus, they must not fall prey to what is referred to as the fallacy of the last move, “in which a proposed innovation is touted as capable of providing a permanent advantage.” 76 Moreover, the identification of the fallacy of the last move must not foster a “fallacy of the second-to-last-move”, in which actors see only one move deeper and decline taking action thinking that it will only be countered. 76 The Bay of Biscay offensive establishes how “a sequence of temporary advantages can be as useful as a permanent advantage.” 76

Undersea warfare and ASW are important components of contemporary thinking on Joint Operational Access. For instance, U.S. undersea warfare capabilities vis-à-vis China are highlighted in discussions of potential Joint Force campaigns. 79 The experience of ORS provides striking parallels to a potential future conflict. One can compare the bomb-proof submarine pens La Pallice to those of Hainan and Qingdao in China. Alternatively, China’s challenge in sallying submarines past the First Island Chain resembles the problems BdU faced exiting the Bay of Biscay, or Gibraltar, or the Northern Passage. On the other hand, U.S. submarines—even if they spend little time on the surface—are still vulnerable to aircraft, with submarine air defenses only in incipient stages of development. Additionally, U.S. forces face major challenges in conducting open-ocean ASW and guarding against structured attacks on the high seas, much like German U-boats threatened convoys with wolf packs.

More broadly, the lessons of ORS demonstrate how today’s Kill Chains and operational concepts are unlikely to be those of the future and would likely evolve during a war. Therefore, a healthy regard for the possibility of tactical or technological surprise undercutting U.S. advantages in submarine warfare or ASW should be exhibited by U.S. forces. Additionally, the experience of ORS demonstrates how narrowly analyzing weapon effectiveness or even entire Kill Chains does not address other crucial factors, such as inventory or force structure; capacity (rate at which kill chains can be executed); or training and proficiency. In these times of rapid technological and tactical change and near-peer competitors, the incorporation of operational research expertise into senior Department of Defense decision-making merits increased attention.

Bibliography

Kenneth Beyer. Q-Ships Versus U-Boats. Annapolis: US Naval Institute Press, 1999.

Donald C. Daniel. 1944-Anti-submarine warfare and superpower strategic stability, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986.

Robert M. Grant. U-Boat Hunters: Code Breakers, Divers and the Defeat of the U-Boats, 1914-1918, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2003.

Holger H. Herwig. “Total Rhetoric, Limited War: Germany’s U-Boat Campaign 1917-1918,” Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, Vol 1, No 1, 1998.

J.R. Hill. Anti-Submarine Warfare. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1985.

Joel Ira Holwitt, “Execute Against Japan: Freedom of the Seas, the U.S. Navy, Fleet Submarines, and the Decision to Conduct Unrestricted Submarine Warfare, 1919-1941”, The Ohio State University, Thesis, 2005.

Edwin P. Hoyt. The U-Boat Wars. New York: Arbor House, 1984.

Edwin P. Hoyt. The Death of the U-Boats. New York: McGraw Hill, 1988.

Wayne P. Hughes. “Naval Operations: A Close Look at the Operational Level of War at Sea”,

Naval War College Review 65.3 (Summer 2012): 22-46.

Brian McCue. U-boats in the Bay of Biscay: an essay in operations analysis. Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 1990.

Montgomery C. Meigs. Slide Rules and Submarines: American Scientists and Subsurface Warfare in World War II. Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 1990.

Philip Morse and George Kimball. Methods of Operations Research. 1st rev. ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1951.

Axel Niestle. German U-Boat Losses During World War II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1998.

Lawrence Paterson. Second U-Boat Flotilla. Yorkshire: Leo Cooper, 2003.

Max Schoenfeld. Stalking the U-boat: USAAF Offensive Antisubmarine Operations in World War II. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995.

David Syrett. The Defeat of the German U-Boats. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1994.

John Terraine. Business in Great Waters: The U-Boat Wars, 1916-1945. London: Leo Cooper, 1989.

Gordon Valeth. Blimps and U-Boats. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1992.

Conrad Hall Waddington. O.R. in World War 2: operational research against the U-boat. London: Elek, 1973.

D.J. White. Operational Research. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, 1985.

(Return to December 2015 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

- Holwitt, Joel Ira. “Execute Against Japan: Freedom of the Seas, the U.S. Navy, Fleet Submarines, and the Decision to Conduct Unrestricted Submarine Warfare, 1919-1941”, The Ohio State University, Thesis, 2005, p. 31. ↩

- Under these rules of international law, merchants could not be sunk without the crew and passengers being first provided an opportunity to disembark. ↩

- Operations research is “a scientific method of providing executive departments with a quantitative basis for decisions regarding the operations under their control.” Philip Morse and George Kimball. Methods of Operations Research. 1st rev. ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1951, 3. ↩

- Max Schoenfeld. Stalking the U-boat: USAAF Offensive Antisubmarine Operations in World War II. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995; Montgomery C. Meigs. Slide Rules and Submarines: American Scientists and Subsurface Warfare in World War II. Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 1990. ↩

- U-boats were more submersibles, or submersible torpedo boats, than true submarines. For ease of reading, however, the author will use the terms U-boat and submarine—instead of submersible. ↩

- Holger H. Herwig, “Total Rhetoric, Limited War: Germany’s U-Boat Campaign 1917-1918,” Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, Vol 1, No 1, 1998, p.1. ↩

- Holwitt, p. 30. ↩

- Holwitt, p. 30. ↩

- J.R. Hill. Anti-Submarine Warfare, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1985, 10. ↩

- Herwig, p. 9. ↩

- Hill, 10. ↩

- Hill, 11. ↩

- John Terraine. Business in Great Waters: The U-Boat Wars, 1916-1945, London: Leo Cooper, 1989, xv. ↩

- John Terraine, 175. ↩

- Meigs, 26. ↩

- Meigs, 26. ↩

- Syrett, 8. ↩

- “U-Boat Force Combat Strength”, U-Boat, http://uboat.net/ops/combat_strength.html. ↩

- Conrad Hall Waddington, O.R. in World War 2: Operational Research Against the U-boat, London: Elek, 1973, 9. ↩

- Philip Morse and George Kimball. Methods of Operations Research. 1st rev. ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1951, 3. ↩

- Waddington, 21. ↩

- Waddington, 31-32. ↩

- It is worth noting that Italy provided an Atlantic Flotilla. They were highly ineffective outside of the Mediterranean and will not be analyzed in this piece, as they did not significantly affect submarine-aircraft dynamics. ↩

- Waddington, 35. ↩

- Hoyt, 119. ↩

- Hoyt, 120. ↩

- Lawrence Paterson. Second U-Boat Flotilla, Yorkshire: Leo Cooper, 2003, vii. ↩

- Meigs, 40. ↩

- Meigs, 41. ↩

- McCue, 7. ↩

- David Syrett. The Defeat of the German U-Boats. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1994, 266. ↩

- Brian McCue. U-boats in the Bay of Biscay: an essay in operations analysis, Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 1990, 18. ↩

- Meigs, 24. ↩

- Waddington, 56. ↩

- Waddington, 100. ↩

- Waddington, 115. ↩

- Waddington, 122. ↩

- McCue, 8. ↩

- Waddington, 122. ↩

- Waddington, 141. ↩

- Waddington, 142. ↩

- McCue, 27. ↩

- Information Based on: Brian McCue. U-boats in the Bay of Biscay: an essay in operations analysis, Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 1990, 31. ↩

- Waddington., 151. ↩

- Waddington, 151. ↩

- Waddington, 165. ↩

- Chart based on information from Waddington, 142. ↩

- Waddington, 168. ↩

- Waddington, 169. ↩

- Waddington, 174. ↩

- Waddington, 177. ↩

- Chart based on information from Waddington, 156. ↩

- Waddington, 194. ↩

- Waddington, 198. ↩

- McCue, 27. ↩

- Waddington, 38-39. ↩

- Hoyt, 191. ↩

- McCue, 22. ↩

- Waddington, 242. ↩

- Paterson, 115. ↩

- Terraine, 494. ↩

- Terraine, 653. ↩

- Waddington, 32. ↩

- Syrett, 18. ↩

- Hoyt, 222. ↩

- Waddington, 247. ↩

- Waddington, 247. ↩

- Waddington, 18. ↩

- Waddington, xiii. ↩

- Waddington, xiii. ↩

- Meigs, 28. ↩

- Waddington, 24. ↩

- Waddington, 9. ↩

- Wayne P. Hughes. “Naval Operations: A Close Look at the Operational Level of War at Sea”, Naval War College Review 65.3 (Summer 2012): 22-46. ↩

- Meigs, 1990. ↩

- McCue, 172. ↩

- McCue, 172. ↩

- McCue, 172. ↩

- Sean Mirski, “Stranglehold: The Context, Conduct and Consequences of an American Naval Blockade of China”, Journal of Strategic Studies, 36:3, 2013, pp. 385-421. ↩