Viktor M. Stoll

University of Cambridge

“They always want everything for themselves…whenever anyone takes anything, the English want to take much more,” foreshadowed Czar Nicholas II to German Chancellor Chlodwig zu Hohenlohe during their discussion on Russo-German Far Eastern territorial ambitions at Peterhof, Russia in 1896. 1 Indeed, the Czar’s observation correctly anticipated the British reaction to Germany’s seizure of Kiaochow Bay, China in January 1898 and Russia’s occupation of Port Arthur, two months later. 2

The British response, the occupation of Weihaiwei in July 1898 – China’s principle northern naval port and home of its premier Beiyang Fleet – cannot only be described as reactionary, but as a passé protectionist approach to stave off Continental competition in Far Eastern commerce and strategic projection. Why did Britain, so long the proponent of the “Open Door” policy of free trade and guarantor of Chinese territorial integrity, adopt such an expansionist attitude toward the “Far Eastern Question” in response to Russo-German territorial expansion in the region? And why, of all the possible acquisitions, did British policy makers seize the poorest concession of all the European powers during the Scramble for China in 1898?

The occupation of the Chinese port at Weihaiwei by Lord Salisbury’s Government (1895-1902), an ostensibly illogical move which disregarded nearly sixty years of British foreign policy in East Asia, dissents sharply with orthodox views on the prime motivations of Britain’s “New Imperialism” in the latter nineteenth century. The myriad modern theses on the causation of Britain’s formal expansion are inadequate for understanding the rationale for this abrupt nullification of Britain’s informal imperial policy in the Far East. These theories, though varied, share common intellectual traditions that may be used to divide the debate into five general thematic approaches: economic, strategic, settler, culture and societal psychology.

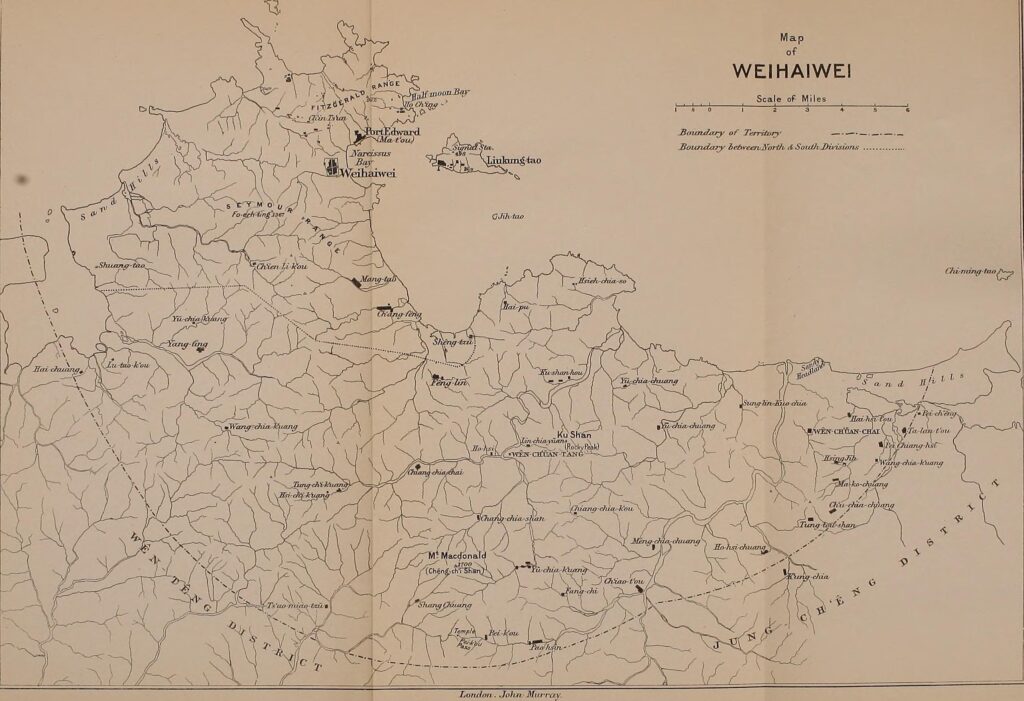

Map of Weihaiwai 1910 in Reginald Fleming Johnston, The Lion and the Dragon in Northern China (New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1910).

Given the substantial, and formerly uncontested, capital investments within China by British economic interests following the Opium Wars (1839-1842, 1856-1860), the many variations of “accumulation theory” seem to superficially justify the annexation of Weihaiwei. According to this theory, the accumulation of surplus capital in Britain following the Industrial Revolution restricted investment within the core and encouraged the pursuit of more profitable investments in the non-European periphery. Lower labour costs, cheaper land and exploitable raw materials provided tempting return-on-investment opportunities for the “Gentlemanly Capitalists”, the united socioeconomic front consisting of Britain’s landed gentry and the financial elite within the City of London. 3

Within accumulation theory, the idea of “underconsumption”, the consequence of this accumulating surplus capital within the core, was first proposed by Karl Marx in Das Kapital (1867) as a prime motive for imperial expansion overseas. 4 Marx believed that the underconsumption of goods within domestic economies was a necessary precursor to the eventual redistribution of wealth via communist revolution, as Western bourgeoisie interests would be unable to adequately redistribute their surplus capital to spur domestic consumption. However, Marx’s liberal detractors demonstrated that foreign markets and overseas expansion could quell social discontent within the core, at least temporarily, and provide ample avenues for surplus capital investment in the colonial periphery.

The liberal re-interpretation of accumulation theory, postulated by J. A. Hobson in Imperialism: A Study (1902) extols the effectiveness of overseas expansion in diffusing social tensions at home by distributing wealth through investment in the periphery. 5 Though Hobson’s theory was subsequently challenged, particularly by Vladimir Lenin in 1916, 6 the effect of economic competition on the spread of Britain’s formal empire during the latter quarter of the nineteenth century provides a compelling approach in which to rationalize the occupation of Weihaiwei.

Furthermore, given Britain’s unrivalled naval supremacy during the long nineteenth century, Hobson’s theory explains the spread of Britain’s informal-commercial empire, and her ultimate move toward formal annexation to protect her share of the global market. As the Industrial Revolution began to transform the Continental powers, chiefly Germany, France and Russia, protectionism and territorial expansion provided the tools with which to usurp Britain’s commercial and financial primacy in the colonial world. 7 Bernard Porter has since suggested that the challenge of these “semi-peripheral” powers forced Britain onto the defensive, thus turning Britain toward formal imperialism as a mechanism to retain her relative economic position when challenged by the emerging neo-mercantilist powers of Europe. 8

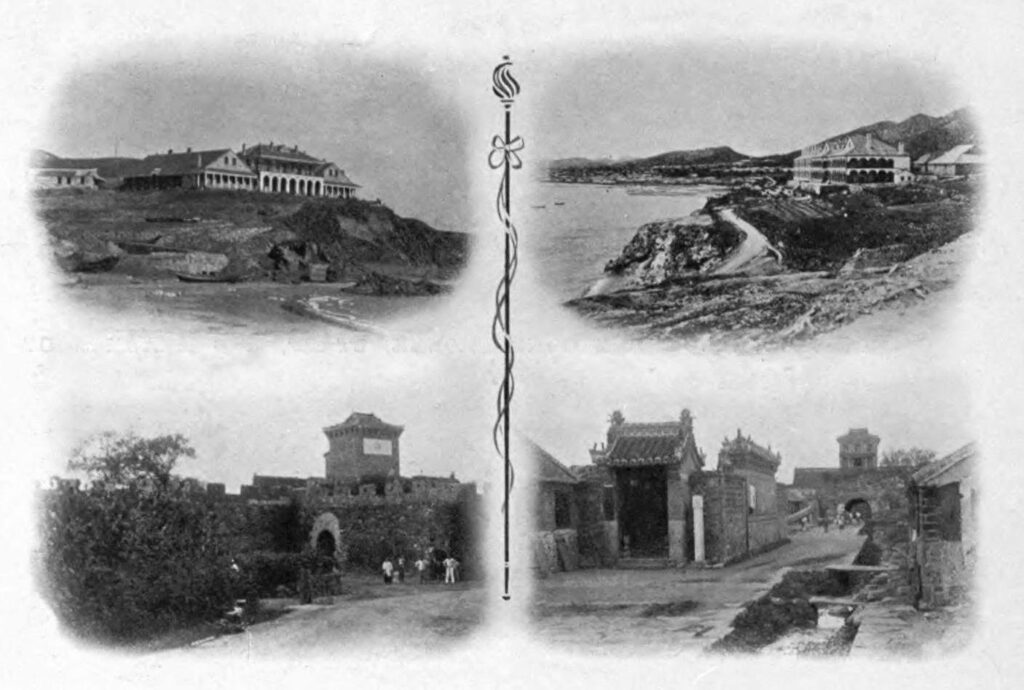

Postcard of British Weihaiwei – 1908 in Arnold Wright, Twentieth Century Impressions of Hong-kong, Shanghai, and other Treaty Ports of China (London: Lloyd’s Greater Britain Pub. Co., 1908).

A counter thesis to accumulation theory, first postulated by John Gallagher and Ronald Robinson in Africa and the Victorians (1961), is found in the seemingly “eccentric” development of Britain’s formal empire. 9 Formal imperial expansion was not dictated by the “Gentlemanly Capitalists”, but by diplomats and bureaucrats within the official nodes of imperial power. Attempts to secure India’s geopolitical defence by this “Official Mind”, particularly her maritime lines of communication with the metropole, drove the British to formally occupy territory from the Transvaal to Egypt to Burma. As Continental imperial powers expanded throughout Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia and Southeast Asia, every non-British acre increased the perceived existential threat to the Raj, the uncontested Crown Jewel of the British Empire.

Still another theory sees settlers as the main driver of Britain’s New Imperialism. James Belich proposed that settler actions within the periphery, particularly the boom-bust economic cycles of the frontier, drove Britain’s formal imperial aggrandizement. 10 Territorial expansion, chiefly in the white settler colonies of Canada, Australia and New Zealand, acted as a demographic safety valve for Britain’s surplus population. However, settler overreach along the ever-expanding colonial frontier often caused the implosion of colonial economic bubbles and dangerous native revolts to White settlement. As these settler societies became increasingly imperiled, Whitehall was obliged to occupy the frontier with British soldiers and extend formal administration in order to prevent a power vacuum that might embolden Britain’s imperial competitors to challenge British rule in the region.

Advocates for a culture-centric approach to Neoimperial expansionism, led by Edward Said, believe that Britain’s formal imperial enlargement was tied to an increasing Western awareness of “Orientalism”. 11 This provided a philosophical justification for the forced “civilizing” of non-Western “others,” a tradition steeped in Lockean preconceptions of improvement of land and people. 12 Best encapsulated by Providence Theory, and often overly attributed to David Livingstone’s triad of “Christianity, Commerce and Civilization”, 13 this social construction was propagated by bureaucrats, missionaries, academics and the popular imagination and reinforced a cultural, and indeed racial, view of the supremacy of the Occident over the Orient. This moral obligation to “improve” non-European “others” drove formal imperial annexations to halt the East African Slave Trade, suppress cannibalism in Papua, and right Qing resistance to British free trade during the Opium Wars.

Lastly, some scholars advocated that formal imperial expansion was an exercise shaped by innate societal psychology. Joseph Schumpeter theorized in The Sociology of Imperialism (1918), that imperial expansion was a pattern of learned, societal behaviour which evolved over centuries of violent confrontation. 14 Such bellicose interactions created a “warrior class” which eventually manufactured threats to maintain its own position within the nation’s political-social hierarchy – principally represented by the senior ranks of the military officer corps. This class utilized martial conflict, which accompanied formal expansion, as the means to make itself indispensable within the social order. Incremental expansion into the periphery, often perpetuated by local “men-on-the-spot” commanders, epitomized by the rolling British penetration of India’s Northwest Frontier during the nineteenth century, provided an enduring rationalization for maintaining the societal position of Britain’s official warrior caste.

However, the rationalization for the British annexation of Weihaiwei falls outside these traditional theoretical approaches which define the historiography of Britain’s New Imperialism. Undoubtedly, the event demonstrates a substantially empowered press-public nexus that, in the case of the late nineteenth century Far East, supplanted the traditional powerbrokers of British imperial policy. This “Public Mind”, 15 to coin a neologism to Robinson and Gallagher’s magisterial work, was truly a trans-colonial phenomenon. A conscience collective, 16 manifested throughout the nodes of the formal British Empire (London, Hong Kong, and Sydney) and became locked in a cycle of self-proliferating hysteria, spiraling towards irrational territorial aggrandizement in Northeast China.

Naturally, the Public Mind always played a role in the shaping of British foreign policy, however, its aspirations were consistently manipulated by Britain’s traditional imperial powerbrokers. These decision makers, like the “Gentlemanly Capitalists” and “Official Mind”, cultivated the Public Mind over the preceding decades to possess a deep anxiety of Russian, and to a lesser extent Franco-German, imperial expansion in order to gain the public support necessary to pursue diverse foreign policy initiatives and imperial actions across the globe. 17 Throughout much of the nineteenth century, and particularly from the First Afghan War (1839-1842) onwards, the Public Mind was cultivated to expect a tough government response to any perceived Russian threat to British imperial interests. 18 In Afghanistan, Persia, and the Balkans, the Public Mind was excited to the point of war in order to demonstrate British resolve against Russian territorial expansion. By the end of the nineteenth century in the Far East, as it did all along the frontier of the Czar’s expanding empire, the Public Mind apprehensively viewed Russia’s opaque encroachment into Manchuria as an existential threat to Britain’s primacy in the region.

The blatant Russian seizure of Port Arthur in March 1898, as well as the surrounding Kwantung Leased Territory on the southern Liaodong Peninsula, finally compelled a British reciprocal response as press-public agitation reached the boiling point. In the case of Weihaiwei, the Public Mind thoroughly trampled more pragmatic imperial interests, demonstrating the primacy of domestic politics as a major catalyst in Britain’s fin de siècle formal imperial expansion in the Far East.

The historiography regarding Britain’s imperial expansion in China mirrors the major theoretical approaches described above and similarly fails to acknowledge the role of the Public Mind in Britain’s New Imperialism. The most iconic works from William L. Langer, Hosea B. Morse and Philip Joseph support a Hobsonian inspired economic causality, but fail to comment on the position of public opinion in directing imperial annexation. 19 Mary H. Wilgus, drawing on the Robinson and Gallagher thesis of informal empire, attempted to define the extent of British informal domination in Qing China, but did not acknowledge the press-public rationalization of Britain’s shift away from the Open Door policy. 20

More recent work has sought to justify the episode as a consequence of the “inherent irrationality of empire”, using Schumpeter’s view on the societal psychology of imperialism. 21 Nevertheless, these theoretical approaches fail to acknowledge the collective power of popular opinion on formal imperial expansion which usurped British policymaking in China in 1898. By examining the case of Weihaiwei, particularly through those media publications and official memoirs which filled the public sphere during the period, it becomes apparent that the Public Mind nearly unilaterally directed Britain’s “New Imperialism” in the Far East.

The Sino-Japanese War and the Intervention of the Dreibund

Sino-Japanese competition over the suzerainty of the Korean Peninsula, ongoing since the sixteenth century, peaked in the summer of 1894. A revolt near Asan brought both Japanese and Chinese armies into the field to support their corresponding Korean factions. The proximity of the two combatants inevitably guaranteed a clash, for which China was ill-prepared. By March 1895, the modernized Imperial Japanese Army had routed the Chinese and were in full control of Korea, Formosa, the Liaodong Peninsula (including Port Arthur), and the main Chinese naval port at Weihaiwei. Japanese preparations for an imminent coup de grâce on Peking coerced the Chinese to capitulate, signing the humiliating Treaty of Shimonoseki on 17 April 1895 and ending the First Sino-Japanese War. 22 This “epoch-making event in the history of the Far East”, as historian William Langer described it, shattered European perceptions about the survivability of the Chinese Celestial Empire and would lead to a scramble for Chinese concessions less than two years later. 23

The terms of the treaty, which included China’s withdrawal from Korea and the ceding of both Formosa and the Liaodong Peninsula, placed a crushing war indemnity of 200,000,000 Kuping taels (£40,000,000) on the Qing Government – an impossible sum to pay without a foreign loan. 24 To ensure payment of the indemnity, the Japanese also insisted on the continued military occupation of Weihaiwei, which dominated the approaches to the strategic Gulf of Chihli (i.e. Bohai Sea) and directly menaced Peking. 25 Russia, France and Germany (known simply as the Dreibund) responded to Japan’s new primacy in Northeast China, and the significant political influence it commanded at Peking, with the belief that the Japanese presence in China would “be a perpetual obstacle to the peace [i.e. the balance of power] of the Far East”. 26

The Dreibund submitted a joint note of disapproval to Japan, and an implied threat of collective military intervention, in April 1895. 27 Faced with fighting a coalition of European Great Powers in order to maintain its gains in China, Japan ultimately capitulated prior to the official ratification of the Shimonoseki Treaty and withdrew from the Liaodong Peninsula and Weihaiwei. However, as compensation, the Dreibund guaranteed that Japan would receive Formosa, and more importantly, the indemnity payment.

Although the Dreibund’s eleventh-hour intervention led to a honeymoon period of amicable affection between the Qing and the Continental European powers, the intervention also created a window of opportunity for the Dreibund to pounce on the hapless Chinese they had so recently safeguarded. As George Curzon, British Undersecretary for Foreign Affairs (1895-98), cynically put forth, “Russia does not render this assistance from a superfluity of unselfishness.” 28 Russia and France, treaty allies since 1894, saw the indemnity payment as the financial lever with which they could usurp Britain’s political and commercial primacy in China.

Afraid that allowing the indemnity loan to be placed on the open market would guarantee a successful British bid to fund Qing reparation payments for decades, and thus further increase British influence in Peking, Russia and France broke faith with Germany and clandestinely convinced the Chinese to accept a Franco-Russian loan of 400,000,000 francs (£16,000,000) to finance the first instalment of their payment to the Japanese. 29 This loan, guaranteed by the Russian Government and substantially underwritten by French banks, was floated to the Chinese at the then absurdly low rate of 4 percent in July 1895. 30

This proposal and a suspected Russian bribe to the influential Qing Viceroy Li Hung-Chang, 31 were rewarded by the signing of a Sino-Russian Agreement (also known as the Li-Lobanov Treaty of 1896) which allowed the construction of a Russian-controlled railway across Manchuria to Russia’s principle naval base at Vladivostok. A separate Russian-controlled spur would lead to Port Arthur, the Chinese port which, thanks to the Russo-Chinese agreement, would now host the Czar’s Pacific Squadron during the winter months when Vladivostok was choked with ice. 32 More importantly, the Franco-Russian alliance gained the power-of-the-purse, and significant political influence, over both the Chinese and Japanese for decades at the expense of their British imperial competitors.

Although much of the Continental press defended Russia’s legitimate right to the “fruits of his political cunning”, specifically when it benefitted other Continental powers, 33 the Sino-Russian Agreement sparked public outrage in London with The Times proclaiming it “would profoundly alter the conditions of our eastern trade.” 34 The conservative Pall Mall Gazette declared, “the treaty means to ruin British trade and lose all money invested in China” and even urged “the immediate occupation of Port Hamilton” in Korea to counter the Russian position. 35 Yet, the Public Mind’s anxiety was not felt by traditional imperial powerbrokers like Thomas Sutherland of the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company. As a “Gentlemanly Capitalist”, Sutherland did maintain “apprehension as to the effects on British trade” but rather demonstrated rationalist restraint by not advocating for any formal imperial expansion. 36

Russian expansionism in the Far East rightfully engendered public consternation in Britain. Prior to the Treaty of Shimonoseki, British firms enjoyed an overwhelming preponderance of Chinese trade. Curzon assessed in 1894 that 60 percent of all Chinese trade was British and 65 percent of all Chinese trade was carried on British bottoms. 37 Langer later put the values even higher, at 65 percent and 85 percent respectively. 38 Furthermore, Britain’s single formal imperial territory in the region, Hong Kong, significantly magnified British informal imperial influence throughout the Far East.

From Hong Kong, Royal Navy vessels could enforce Britain’s Open Door policy in twenty-four Chinese treaty ports, opened to foreign trade after the Opium Wars, which were the key in exploiting China’s interior markets. 39 Moreover, the British maintained the naval capacity to cut off the near entirety of Peking’s grain supplies by blockading the Yangtze River – Grand Canal route. This capability, successfully tested during the Opium Wars, could starve the Chinese capital at will. 40 Such naval supremacy based on the position at Hong Kong, in addition to the commercial supremacy of the British merchant fleet, provided a powerful bargaining chip in any negotiations with the Qing Government.

Perhaps more significant were Hong Kong’s substantial shipyards, which all European-Far Eastern shipping required for repairs and safe harbour. Alfred von Tirpitz, at the time German Naval Secretary, recounted that maintenance queues in Hong Kong regularly exceeded nine months and non-British traders and naval squadrons had to avoid incurring British ill-favour, unless they desired to be marooned in Victoria Harbour. 41 No European maritime presence, either commercial or naval, could survive long in the Far East without the use of Hong Kong’s modern shipyards.

Additionally, British financial interests had issued nearly £10 million in loans to the Chinese Government, with rates as high as 7 percent, on which the Chinese were still paying in 1895. 42 The unique British presence at Hong Kong, combined with deep fiscal penetration of the Qing Government, allowed Lord Palmerston’s “watchful eye and strong arm of England.. [to] protect every Englishman…from injustice and wrong doing” 43 via the prudent use of informal imperial influence.

Despite preponderant British trade in the Far East and the “furious” reaction by the British press towards perceived Russian attempts to ruin it, was the move by Russia considered a genuine menace by Britain’s imperial powerbrokers? 35 Assuming Russia did maintain considerable influence over Li Hung-Chang, that clout would not have extended far beyond the boundaries of Peking. 45 Li’s power in the rest of China, specifically the treaty-ports, was almost non-existent and perpetually accosted by intriguing court “sensors” and semi-autonomous regional governors. Even Li’s influence in Peking was rapidly collapsing, as demonstrated by his fall from the Qing Emperor’s grace following his disastrous handling of the war with Japan. 46

Furthermore, the Dreibund intervention and Franco-Russian break with Germany created a paradigm shift in Great Power relations, which further supported British supremacy in the region. Dreibund meddling in the Far East, particularly the encroachment of Russia, was already propelling Japan into Britain’s sphere even before the crisis subsided. As early as June 1895, Count Hayashi, Japanese Vice-Minister for Foreign Affairs, proposed an Anglo-Japanese alliance to oppose Russian advances in the Far East. 47 Indeed, the Sino-Russian Agreement provided the initial catalyst for the future Anglo-Japanese Alliance (1902-1922), signed four years after the official Russian occupation of Port Arthur. This alliance became the cornerstone of British foreign policy in the Far East until the 1920’s and alleviated the need for a large Royal Navy presence on the China Station (i.e. Hong Kong). In fact, it was Britain’s Japanese allies who spectacularly crushed the Russians in the Far East during the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). This confluence of Anglo-Japanese security interests allowed Britain to safely reinforce the Home Fleet at the expense of its East of Suez force posture as tensions with Germany rose before World War One.

Likewise Germany, furious with being duped by her Dreibund co-conspirators 48 , sought a new strategic understanding with Britain – both in Europe and the Far East. Russian expansion was such a threat to both parties, that the German and British Governments pursued formal alliance talks for several years afterwards. 49 Although an Anglo-German alliance, and a possible incorporation of Britain into the Triple Alliance, ultimately came to naught, Germany and Britain did form a financial partnership in the Far East, which successfully countered the influence of the Franco-Russian loan. Britain’s opportunistic coordination with Germany secured a further £32,000,000 in loans for the Chinese indemnity payments to Japan, double that of the Franco-Russian syndicate. 50 As a result of Russia’s formal imperial expansion, Britain was actually in a far stronger position in the Far East, militarily, politically and economically, following the Sino-Russian Agreement.

Indeed, an informal Open Door faction at Whitehall, which fully understood the nearly unassailable British position in the region, held firm on the continuation of informal imperial influence in the Far East. 51 Pursuing British interests without territorial aggrandizement remained the Government’s official and highly effective strategy, as the Anglo-German loan and Anglo-Japanese strategic convergence demonstrates. Arthur Balfour, concurrently First Lord of the Treasury and Leader of the House of Commons, stated that the Government “neither feared nor envied the growth of [non-British] industries” in the region and that healthy competition benefited British commerce. 52 However, continued Russian encroachment soon animated the Public Mind to turn against the Government’s cavalier approach to the Far Eastern Question.

Weihaiwei and the Scramble for China in 1898

The potential influence which the Public Mind could bring to bear on British imperial policy in the Far East was identified by astute British policy makers even before word of Chinese concessions began to resonate in Europe’s metropoles. As early as 1895, Czar Nicholas informed Kaiser Wilhelm that he “would have nothing against [Germany] acquiring” a coaling station in China. 53 Confluent with Nicholas’ demeanour, Count Mikhail Muraviev (alt. Muravyov), the Russian Foreign Minister, gave his tacit approval to Prince von Bülow, German Secretary of State, in August 1897. 54 By November, the Kaiser gained an excuse to realize the Far Eastern territorial ambitions of his Weltpolitik after two German missionaries were murdered in the Shandong Peninsula. 55

In response, Bülow approached the Russian and British Ambassadors in Berlin for their support of the German seizure of Kiaochow Bay, the catalyst that set off the Scramble for China in early 1898. While the Russians demanded the formal occupation of Port Arthur as compensation, British Ambassador to Berlin, Frank Lascelles, readily disputed the potency of his government’s cautious Open Door policy. Lascelles believed that any public perception of a threat to British Far Eastern trade would so agitate the press that the British Government would be forced to seek a port in the Gulf of Chihli to appease public opinion. 56 By January 1898, Germany’s “gepanzerte Faust” had firmly seized hold of Kiaochow 57 , by late March Russian troops had officially taken over Port Arthur, and by early April, the Public Mind believed that Britain’s Open Door policy needed to be sacrificed to maintain her Far Eastern primacy.

Frank Lascelles’ prediction at the cusp of the Scramble for China was veracious. The Public Mind was indignant with the position held by Britain’s traditional imperial policy makers particularly regarding Russia’s acquisition of formal Chinese concessions in early 1898. Joseph Chamberlin, Secretary of State for the Colonies, predicted “grave trouble impending on the Government” if they did not “adopt a more decided attitude in regards to China.” 58 Chamberlin, no doubt, could smell the blood-in-the-water that would bring the Unionist “imperial-nationalist” backbenchers swarming against the Old Hats of the Salisbury Cabinet. 59 Yet despite the increasing panic at Whitehall, Britain’s imperial powerbrokers still resisted the Public Mind’s calls for knee-jerk territorial aggrandizement.

A week after Germany’s occupation of Kiaochow, Salisbury’s Government began an aggressive diplomatic campaign to neuter any corresponding British territorial expansion on 10 January 1898. Balfour, now Acting Foreign Secretary on account of Salisbury’s bout with Bright’s Disease 60 , unequivocally stated that acquisition of any “territory [in China]…is a disadvantage rather than an advantage [for the British]” and that the Government “asked [only] for freedom of trade.” 61 Balfour’s position amounted to the Government’s first attempt to control the narrative of the developing “Far Eastern Crisis” by allaying the Public Mind’s fear that trade might be irrecoverably injured by the formal imperial expansion of Continental competitors.

Michael Hicks Beach, Chancellor of the Exchequer, went further stating that “at the cost of war…the door [to China] should not be shut against us”. 62 Britain was ready to fight to maintain the Open Door, as it had in the past, but it would not seek territorial aggrandizement at the expense of the hapless Chinese. This determined Open Door stance of the Salisbury Government galvanized British public opinion and temporarily satiated the expansionist appetite of the Public Mind. It even led to an Anglo-American attempt to codify a “Monroe Doctrine” in China that would guarantee a free-trade “Open Door” for all powers throughout the Qing Empire while prohibiting further formal annexations. 63

However, as Russian efforts continued unabated and Czarist troops officially took possession of Port Arthur on 27 March 1898, the Public Mind’s agitation for formal expansion to halt the Russian advance became relentless. Though Lord Selborne, Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, declared on 01 April 1898 that Britain’s informal imperial policy in China “was still intact” 64 , The Standard reported that nearly all newspapers along the political spectrum and across the empire were united in strong condemnation of the Government’s impotence in the matter. 65 Reuters went so far as to declare that British diplomacy had suffered a “crushing defeat” at the hands of the Russians. 66 But Britain’s imperial powerbrokers were still not convinced by the Public Mind’s conjuring of the Russian bogeyman at Port Arthur.

Balfour, considered one of the greatest geopolitical strategists of the day, rightfully believed that any Russian gain in Port Arthur was strategically negligible to Britain’s regional position since “[Russia’s political] influence at Peking depends principally on her land position [in Siberia and the Far East]”. 67 The primacy of the Czar’s Far Eastern land position vis-à-vis its naval posture, was only growing as construction of the Trans-Siberian Railroad progressed. The relatively weak Russian Pacific Squadron, whether in Vladivostok or Port Arthur, presented a negligible naval threat to Britain, while the Empire simply did not have the means to directly counter Russian influence deep within Manchuria. For the “Official Mind”, the balance of power in the Far East was still intact despite the Russian occupation at Port Arthur.

However, as early as 26 March, some in the Cabinet, fearful of the Public Mind’s rapidly swelling outrage, were already arguing that Britain should move to specifically acquire Weihaiwei to counter the Russian naval position across the Gulf of Chihli, a day before the formal Russian occupation of Port Arthur. Even Queen Victoria, a unflinching supporter of the Open Door policy for nearly half-a-century, was so unsettled by the assertions of the Public Mind that she chastised the Government’s continuation of the Open Door policy in the face of Russian expansion as full of “very foolish and dangerous lies.” 68 The intensity of the Public Mind’s protest was now overwhelming the rationalist decision making of British imperial policy.

Salisbury’s Government nearly fell in the week after Russia’s formal occupation of Port Arthur, and by 4 April 1898 Whitehall completely kowtowed to the pressure of the Public Mind by entering into preliminary negotiations with the Qing Government for a lease at Weihaiwei. 69 Balfour and the Open Door faction capitulated and the new policy of formal territorial acquisition received approval in the House of Commons a few days later.

On 1 July 1898, “for the better protection of British commerce”, Weihaiwei was officially leased to Britain for as “long a period as Port Arthur shall remain in the occupation of Russia.” 70 It is important to note the wording of the Weihaiwei convention, which specifically ties the British lease to Russia’s position at Port Arthur. Neither Germany’s acquisition of Kiaochow, nor the subsequent French concession of Kouang-tcheou-ouan, both of which were arguably just as, if not more, economically and strategically important to British primacy in the Far East, are mentioned in the treaty.

This lease was specifically meant to counter the publicly perceived Russian naval threat to Britain’s supremacy in the Far East, a threat which the “Official Mind” found negligible compared to the Russian land position in Manchuria. The specific inclusion of “Russia” in the lease allowed Salisbury’s Government to undeniably counter the Public Mind’s claims that not enough was being done to limit Russian adventurism in the region.

Ultimately, the Weihaiwei Concession had far more to do with the demands of the Public Mind, than it did with checking Russian influence or maritime power in the region. Britain’s imperial powerbrokers, assailed by the Public Mind’s territorial expansionist demands, ultimately betrayed the Open Door policy which formed the root of British economic and strategic success in the Far East for over half a century. But did the capitulation of Salisbury’s Government in the face of the Public Mind at Weihaiwei provide any substantial benefit to Britain’s traditional imperial interests?

Rationalizing Weihaiwei and the Abandonment of the “Open Door”

While the seizure of Weihaiwei was welcomed by both China and Japan as a reassuring counterbalance to Russian influence, 71 it ultimately did not improve Britain’s commercial, strategic, political or naval stake in the Far East. Given Russia’s growing assertiveness in Manchuria after the Sino-Russian Agreement, the Chinese had already turned toward Britain as an ally-of-convenience by early 1898. Indeed, the results of Balfour’s Open Door diplomatic offensive guaranteed far more advantageous economic concessions than the formal occupation of Weihaiwei. On 11 February 1898, following the granting of the German concession, China formally declared that the entire Yangtze River basin, which was “of the greatest [commercial] importance to China”, would never be alienated to another power. 72 This officially confirmed Britain’s preeminent commercial position in Shanghai and Central China writ large.

Moreover, on 13 February the Chinese announced that the next Inspector General of Maritime Customs, the office, which controlled Chinese international commerce and was enviously coveted by Russia for decades, would be filled by another Englishman once Sir Robert Hart retired. 73 Only two weeks after the Maritime Customs announcement, the second Anglo-German loan of £16,000,000 to the Qing was finalized, officially doubling the earlier Franco-Russian investments. 74 Thus, nearly a month before Russian troops occupied Port Arthur, Balfour’s diplomatic initiative had substantially increased Britain’s already dominant financial, commercial and, ultimately, political position in the Qing Empire.

In comparison to the significant concessions gained by Balfour’s Open Door diplomatic offensive, the lease at Weihaiwei failed to guarantee the best conditions for commercial exploitation within the Shandong Peninsula. This would suggest that Britain’s powerful economic and financial lobbies, the “Gentlemanly Capitalists”, were not actively involved or consulted in the hasty drafting of the lease. Indeed, no commercial concessions were acquired and the British officially abdicated any future commercial claims throughout the Shandong Peninsula, including the critically important railway concessions, to Germany on 20 April. 75

In comparison, Germany’s ninety-nine year lease of Kiaochow Bay included exclusive mining and manufacturing rights within fifty kilometres of the bay, construction of two major rail lines linking the Shandong Peninsula to Peking, and a ten mile exclusive mining zone on either side of the railways. 76 Furthermore the Russian seizure of Port Arthur, the primary reason for Britain’s occupation of Weihaiwei, was accompanied by exclusive commercial rights to the entire Liaodong Peninsula, closing off the vast territory to all foreign competition. 77 Even the French ninety-nine year lease of Kouang-Tchéou-Wan guaranteed the French exclusive use of the surrounding 1,300 square kilometres of territory. 78, Documents Diplomatiques – Chine, 1898-1899, Ministére des Affaires éntrangéres, No. 1 (Paris: 1900), p. 4.]

The apathetic abdication of commercial rights on the Shandong Peninsula to Germany, combined with the nearly non-existent concessions obtained from the Chinese within the lease’s narrow limits, plainly negates the influence of British commercial or financial interests in promoting territorial aggrandizement in China. These interests, long accustomed to dominating Chinese economic transactions, would have certainly extracted far larger concessions if actively involved in the negotiations.

The attitude of the Government towards Weihaiwei’s economic potential was best summarized by Lord Salisbury who believed, “it is not possible to make Weihaiwei a commercial port…it would never be worthwhile to connect it with the interior.” 79 The official review of the territory by the Foreign Office before the start of negotiations with the Qing confirmed that the trade of Weihaiwei could never “develop to any great extent.” 80 The accuracy of these economic assessments were validated following the acquisition, as the territory ran deficits often exceeding 100 percent of revenue until its ultimate repatriation in 1930, while neither the British government nor any British commercial syndicate pursued any major economic development there. 81

Surplus capital within the core, the foundation of accumulation theory, also clearly did not spur the seizure of Weihaiwei as an outlet for investment. Prior to the occupation of Weihaiwei, British financial interests already controlled over 70 percent of China’s sovereign debt while commercial interests controlled up to 65 percent of its foreign trade. 82 Though Continental powers made minor inroads into Far Eastern commerce in the preceding decades, particularly Germany, Cain and Hopkins’ “Gentlemanly Capitalists” continued to dominate the Chinese economy even after 1898. With the guaranteed succession of a British Inspector-General of Chinese Maritime Customs, and the unrivalled political influence of British financial syndicates like the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, British economic hegemony was assured for decades without Weihaiwei’s occupation.

Moreover, from the perspective of naval projection, contemporary naval experts viewed the port as of little value to Britain’s modern navy despite its location on the Bohai Straits. Only the port and a thin ten-mile buffer zone were ultimately obtained in the lease, offering insufficient defensive depth to counter land-based threats when compared with the German, French and Russian concessions. Possessing a shallow harbour incapable of sheltering British capital ships, and surrounded by hills that required an extensive re-fortification program to protect the port from direct land-based artillery attack, naval decision makers at the British Admiralty were not thrilled with their new acquisition. 83

In fact, the Admiralty was not formally consulted at any level during the negotiations for Weihaiwei. 84 In comparison, the expansion of Hong Kong’s boundaries north of Kowloon (i.e. The Northern Territories), Britain’s only other major concession during the Scramble for China, was based primarily on the creation of a new landward defensive perimeter around Victoria Harbour. British Army and Admiralty officials were front-and-centre during these negotiations. Military surveyors, taking into account recent innovations in siege artillery range and accuracy, carried out on-the-ground assessments to identify the most favourable defensive terrain before the boundaries of the lease were finalized. 85 Given that the negotiations for the New Territories were conducted simultaneously with those of Weihaiwei, the lack of any military participation in the latter clearly negates the influence of this key group of Robinson and Gallagher’s “Official Mind”.

Although the Admiralty took proactive steps to develop a defence scheme for Weihaiwei after the signing of the lease, particularly to counter a possible Russian cruiser raid, the Royal Navy’s consensus was that only substantial defensive and facility improvement would bring Weihaiwei up to the standard of a serviceable naval port. 86 Assessments on-site and within the Admiralty after the occupation never considered Weihaiwei as a replacement to Hong Kong or a strategic platform with which to project naval power in the region at all. During the entirety of its occupation, the port acted only as a limited support facility for limited naval operations in the area – like treaty port visits and cruiser patrols. 87

The policies of both the Admiralty and Foreign Office following annexation undoubtedly contradict the proposed geopolitical usefulness of Weihaiwei. Despite the importance of a secured telegraph line to the new naval base, cost estimates for its construction were high enough that the Admiralty simply abandoned plans for an “all red” submarine cable from Hong Kong, relying instead on Russian and Chinese controlled land lines for communication needs. 88 Furthermore, the plans to use the territory as a continually occupied naval base were abandoned by 1902 in the immediate aftermath of the Boxer Crisis and Weihaiwei degenerated into a summer port-of-call for the China Squadron based in Hong Kong. A Royal Navy health spa was established and British personnel frequented the baths beneath the decrepit Qing-era land fortifications during their summer cruises. 89 The “Official Mind” of Britain’s New Imperialism, always cognizant of strategic vulnerabilities, held a complete lack of interest in Weihaiwei.

British China Squadron at Weihaiwei – 1908 in Arnold Wright, Twentieth Century Impressions of Hong-kong, Shanghai, and other Treaty Ports of China (London: Lloyd’s Greater Britain Pub. Co., 1908).

Traditional commercial and strategic theories on the causation of Britain’s formal imperial expansion are thus completely inadequate in explaining the occupation of Weihaiwei. Neither does Belich’s thesis on “settlerism”, Said’s critique of Orientalism, nor Schumpeter’s theory on the societal psychology of empire address the reasons for the occupation. British citizens in the territory never exceeded a few hundred, compared with 150,000 Chinese, and no major settler advocacy lobby ever materialized. 90 Indeed, local administration within the lease remained in the hands of Qing officials and British administrative authority was purposefully relegated to the naval port itself. Furthermore, the “improvement” rationalization did not apply to Weihaiwei because of its time-constrained “lease” status. This administrative category meant that the territory fell under the Foreign Jurisdiction Act of 1890, restricting British jurisdiction over Chinese subjects and limiting the legality of any “civilizing” mission.

Likewise, what Schumpeter would consider Britain’s warrior class found no excuse for the type of warfare in the Far East that defined the more martial atmospheres in Africa or the Northwest Frontier. The British presence at Weihaiwei was officially sanctioned and respected by the indigenous power, thus removing any pretext for localized military action. Moreover, Britain’s warrior class perceived any genuine confrontation with a Continental power, Russia or otherwise, as both hazardous and unnecessary to maintain their status within Britain’s domestic social hierarchy.

It seems that the Public Mind enjoyed far greater influence in Britain’s imperial ventures, particularly in the late nineteenth century, than standing hypotheses acknowledge. As Chamberlin pointed out, a possible fall of Salisbury’s Government was believed inevitable if Whitehall did not act publicly and decisively following the Russian occupation of Port Arthur. At Weihaiwei, the indomitable anxiety of the Public Mind usurped the rationality of Britain’s traditional imperial powerbrokers. For these established imperial interests, the seizure of Weihaiwei was, as J.R. Seeley famously declared, simply a “fit of absence of mind”. 91

As Frank Lascelles predicted, the irrationally Russo-phobic Public Mind, rationally cultivated by Britain’s traditional imperial interests throughout the nineteenth century, proved uncontrollable at Weihaiwei. From the Balkans to Central Asia to the Far East, Britain’s traditional powerbrokers had, in an effort to legitimize their own particular imperial policies to domestic audiences, trained the Public Mind to battle the Russian menace wherever he surfaced. Now at Weihaiwei, the tail of British imperialism was wagging the dog.

Ultimately, the Weihaiwei case offers a cautionary tale of basing-rights “creep” for modern governments seeking to secure regional primacy via the establishment of forward-postured naval forces during a new era of Geopolitical Competition. The Public Mind’s propensity for self-proliferating hysteria can quickly spin out of control, forcing normally rational decision making into illogical and damaging foreign policy choices. In an era of 24-hour news cycles and endless reinforcement in the echo chamber of social media, inflated external threats meant to secure press-public support for certain policy objectives can swiftly usurp rational decision-making processes. As Nietzsche aphorized in Beyond Good and Evil, ironically penned during the height of the Anglo-Russian antagonism, whoever battles monsters should be careful not to create a monster in the process. 92 Indeed, the Public Mind had become a populist monster and the traditional powerbrokers of British imperialism were unable to contain its voracious appetite at Weihaiwei.

(Return to December 2021 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

- “Sie wollen immer…viel mehr nehmen.” Czar Nicholas II to Prince Chlodwig von Hohenlohe, St. Petersburg, 11 September 1896, in Chlodwig Hohenlohe, Denkwürdigkeiten des Fürsten Chlodwig zu Hohenlohe-Schillingfürst, (ed.) Friedrich Curtius, Vol. 2 (Stuttgart: 1907), p. 521. ↩

- Germany occupied Kiaochow (Kiautschou) Bay on 04 January 1898, Russia occupied the Liaodong Peninsula (including Port Arthur) on 27 March 1898, France occupied Kouang-Tchéou-Wan (Guangzhou Bay) on 27 May 1898, and Britain officially occupied Weihaiwei on 1 July 1898. ↩

- P. J. Cain and A. G. Hopkins, British Imperialism: Innovation and Expansion, 1688-1914 (London: Routledge, 1993). ↩

- Karl Marx, Das Kapital: Kritik der politischen Oekonomie (Hamburg: 1867). ↩

- J. A. Hobson, Imperialism: A Study (London: 1902, available through Michigan University Press: Ann Arbor Paperbacks, 1964). ↩

- Vladimir Lenin, Imperialism, The Highest Stage of Capitalism (Petrograd: 1916, available through Martino Fine Books, Eastford, Connecticut, 2011 reprint). ↩

- This thesis on non-British imperial expansion was first postulated by Immanuel Wallerstein as part of his “World-Systems” theory. Immanuel Wallerstein, The Modern World System (New York: Academic Press, 1974). ↩

- Bernard Porter, The Lion’s Share: A Short History of British Imperialism, 1850-2004 (London: Pearson, 2004). ↩

- Ronald Robinson and John Gallagher with Alice Denny, Africa and the Victorians: The Official Mind of Imperialism (London: I.B. Tauris, 1961). ↩

- James Belich, Replenishing the Earth: The Settler Revolution and the Rise of the Anglo-World, 1783-1939 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009). ↩

- Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage, 1978). ↩

- Richard Drayton suggests that the rise of the natural sciences were a direct result of this “improvement” narrative, subordinating science to support formal expansion. Richard Drayton, Nature’s Government: Science, Imperial Britain, and the “Improvement” of the World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000). ↩

- Brian Stanely, “’Commerce and Christianity’: Providence Theory, the Missionary Movement, and the Imperialism of Free Trade, 1842-1860”, The Historical Journal, Vol. 26, No. 1 (March: 1983), pp. 71-94. ↩

- Joseph Schumpeter, Imperialism and Social Classes, (trans.) Heinz Norden (New York: 1951, available through Martino Fine Books Eastford, Connecticut, 2014 reprint). ↩

- The term “Public Mind” has been used to describe the colonial interests of the Gentlemanly Capitalists of Cain and Hopkins fame. I believe that the term better fits a public-press nexus, given the elite status of the Gentlemanly Capitalists within British imperial decision making. Peter Cain and Anthony Hopkins, “Gentlemanly Capitalism and British Expansion Overseas II: New Imperialism, 1850-1945”, The Economic History Review, XL, No. 1 (1987), pp. 1-26; C. M. Andrew, “The French Colonialist Movement during the Third Republic: The Unofficial Mind of Imperialism”, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Fifth Series, XXVI (1976), pp. 143-166. ↩

- A concept first developed contemporaneously to the Weihaiwei acquisition. Émile Durkheim, De La Division Du Travail Social (Paris: 1893). ↩

- In the Far East, the Russians were widely viewed within the British Foreign Office as the empire’s main antagonist in the region by 1890. T. G. Otte, The Foreign Office Mind: The Making of British Foreign Policy, 1865-1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 202-209. ↩

- For a summary of Anglo-Russian relations during the nineteenth century, see: A. Lobanov-Rostovsky, “Anglo-Russian Relations through the Centuries”, The Russian Review, VII, No. 2 (Spring 1948), pp. 41-52. At the turn of the twentieth century, many lay observers believed that a final military confrontation between Britain and Russia throughout Asia was “inevitable”. Demetrius C. Boulger, “Antagonism of England and Russia”, The North American Review, CLXX, No. 523 (June 1900), pp. 884-896. ↩

- William L. Langer, The Diplomacy of Imperialism, 1890-1902, Vol. 1 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1935); Philip Joseph, Foreign Diplomacy in China, 1894-1900, A Study in the Political and Economic Relations with China (London: 1928); Hosea B. Morse, The International Relations of the Chinese Empire (London: 1918, reprint available through Sagwan Press, Glencoe, Illinois, 2015). ↩

- Mary H. Wilgus, Sir Claude MacDonald, the Open Door, and British Informal Empire in China, 1895-1900 (London: Routledge, 1987). ↩

- Clarence B. Davis and Robert J. Gowen, “The British at Weihaiwei: A Case Study in the Irrationality of Empire”, The Historian, LXIII, Is. 1 (September 2000), pp. 87-104. ↩

- Historical Section of the Foreign Office, Peace Handbooks, No. 73 (London: 1920), pp. 68-70. ↩

- William L. Langer, The Diplomacy of Imperialism, 1890-1902 (New York: Random House, 1951), p. 175. ↩

- Article IV, Traité de paix entre le Japon et la Chine de Shimonoseki, 17 April 1895, in Nagao Ariga, La Guerre Sino-Japonaise: Au Point de vue du droit International (Paris : 1896), p. 291. ↩

- Peace Handbooks, No. 73, p. 71. ↩

- Tadasu Hayashi, The Secret Memoirs of Count Tadasu Hayashi, (ed.) A. M. Pooley (New York: Eveleigh Nash, 1915), p. 85. ↩

- “Buitenland”, Nieuwsblad van het Noorden (Groningen), 24 April 1895. ↩

- Earl of Ronaldshay, The Life of Lord Curzon: Being the Authorized Biography of George Nathaniel, Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, K.G. (London: Benn, 1928), p. 276. ↩

- North -China Herald (Shanghai), 31 May 1895. ↩

- Hosea B. Morse, The International Relations of the Chinese Empire, (London: 1918, reprint available through Sagwan Press, Glencoe, Illinois, 2015), Vol. 3, p. 448. ↩

- Langer, The Diplomacy of Imperialism, p. 403. ↩

- The Argus (Melbourne), 30 October 1895. ↩

- “Tout cela a été … es autres puissances?” Le Temps (Paris), 26 October 1895. ↩

- The Times (London), 25 October 1895. ↩

- The Mercury (Hobart), 28 October 1895. ↩

- The China Mail (Hong Kong), 15 July 1895. ↩

- George N. Curzon, Problems of the Far East: Japan-Korea-China (London: 1894), pp. 302. ↩

- Langer, The Diplomacy of Imperialism, p. 167. ↩

- Curzon, Problems of the Far East, p. 303. ↩

- The British first accomplished this feat of starvation warfare during the Yangtze expedition of the First Opium War (1842). Daniel R. Headrick, “The Tools of Imperialism: Technology and the Expansion of European Colonial Empires in the Nineteenth Century”, The Journal of Modern History, LI, No. 2 (June 1979), pp. 231-263. ↩

- Alfred von Tirpitz, My Memoirs (New York: 1919, Vol. II reprint available through Lucknow Books, of Uttar Pradesh, 2013), pp. 95-97. ↩

- Morse, The International Relations of the Chinese Empire, p. 448. ↩

- Lord Palmerstone House of Commons Debate, 20 June 1850. In The Foreign Policy of Victorian England, 1850-1902, (ed.) Kenneth Bourne (Oxford: Oxford University Press,1970), No. 54, p. 303. ↩

- The Mercury (Hobart), 28 October 1895. ↩

- J. O. P. Bland, Li Hung-Chang (London: 1917). ↩

- Trumbull White, The War in the East: Japan, China and Korea (Philadelphia: 1895), p. 510. ↩

- Hayashi, The Secret Memoirs, p. 114. ↩

- “Auch über die…unserm Rücken abgeschlossen.” Fürst von Radolin to Hohenlohe, 09 August 1895, Die Grosse Politik der Europäischen Kabinette: 1871-1914, (ed.) Johannes Lepsius, Albrecht Bartholdy, Freidrich Thimme, (Berlin: 1924), Vol. IX, No. 2290, p. 312. ↩

- Edgar N. Johnson and John Dean Bickford, “The Contemplated Anglo-German Alliance: 1890-1901”, Political Science Quarterly, XLII, No. 1 (March 1927), pp. 1-57; Paul M. Kennedy, “German World Policy and the Alliance Negotiations with England, 1897-1900”, The Journal of Modern History, XLV, No. 4 (December 1973), pp. 605-625. ↩

- Morse, The International Relations of the Chinese Empire, pp. 54. ↩

- This unofficial faction included Prime Minister Salisbury (Robert Gascoyne-Cecil), Treasury Lord (and later Foreign Secretary) Arthur Balfour, and Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlin. ↩

- The China Mail (Hong Kong), 11 December 1896. ↩

- Dann sagte der Kaiser…eine Kohlenstation zu haben.” Nicholas II to Hohenlohe, 11 September 1895, St. Petersburg. Hohenlohe, Denkwürdigkeiten, p. 521. ↩

- Bernhard von Bülow, Prince von Bülow Memoirs, 1897-1903, (ed.) Franz von Stockhammern, (trans.) F. A. Voigt, (London: 1931), Vol. 1, p. 89. ↩

- Langer, The Diplomacy of Imperialism, p. 451. ↩

- Bülow, Memoirs, p. 181. ↩

- Bülow, Memoirs, p. 199. ↩

- Chamberlin to Balfour, 03 February 1898, in Peter Lowe, Britain in the Far East: A survey from 1819 to the present (London: 1981), p. 64. ↩

- For more on the role played by the young and boisterous “imperial-nationalist” backbenchers within the Unionist Government of Salisbury and, ultimately, its Foreign Policy direction, see: T. G. Otte, The China-Question: Great Power Rivalry and British Isolation, 1894-1905 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007). ↩

- Anonymous, “Lord Salisbury’s Illness: British Premier Said to be a Sufferer from Bright’s Disease”, The New York Times (New York), 13 March 1898. ↩

- Philip Joseph, Foreign Diplomacy in China, 1894-1900: A Study in Political and Economic Relations with China (London: 1928), p. 235. ↩

- Langer, The Diplomacy of Imperialism, p. 465. ↩

- Diplomaticus, “A Monroe Doctrine for China”, Fortnightly Review, 01 February 1898. ↩

- “The Policy of the Open Door Intact”, The West Australian (Perth), 01 April 1898. ↩

- The Standard (London), 30 March 1898. ↩

- Reuter’s Telegram (London), 01 April 1898. ↩

- Balfour to Victoria, 26 March 1898. Queen Victoria, The Letters of Queen Victoria: A Selection from Her Majesty’s Correspondence and Journal between the Years 1886-1901, (ed.) George Earle Buckle (London: 1932), Vol. III, p. 238. ↩

- Victoria to Balfour, 04 April 1898. Ibid, p. 239. ↩

- The Times (London), 04 April 1898. ↩

- Convention for the lease of Wei-hai-wei, 01 July 1898. Treaties and Agreements with and Concerning China, 1894-1919, (ed.) John V. MacMurray (London: 1921), Vol. I, No. 1898/14, pp. 152-153. ↩

- “Engeland en China”, Algemeen Handlesblad (Amsterdam), 04 April 1898. ↩

- Tsung-Li Yamen to Sir Claude Macdonald (British Ambassador at Peking), 11 February 1898. MacMurray, Treaties and Agreements, pp. 104-105. ↩

- Tsung-Li Yamen to Macdonald Correspondence, 10-13 February 1898. Ibid, pp. 105-106. ↩

- Agreement for the Chinese Imperial Government 4.5% Gold Loan of 1898, 01 March 1898. Ibid, p. 107. ↩

- Lascelles to Bulow, 20 April 1898. MacMurray, Treaties and Agreements, p. 152. ↩

- Convention respecting the lease of Kiaochow, 06 March 1898. Ibid, pp. 115-116. ↩

- Additional agreement defining the boundaries of the leased and neutralized territory in the Liaotung Peninsula, 07 May 1898. Ibid, pp. 127-128. ↩

- “Les naviers…ouverts de Chine”, Article V, Projet de Convention Relative à Kouang-tcheou-ouan, 27 May 1898, Tsong-li-yamen. Bibliothéque du Ministére des Affaires éntrangéres [BMAé ↩

- Salisbury to Lascelles, 02 April 1898. Peace Handbooks, No. 71, p. 53 ↩

- Ibid, p. 54. ↩

- In 1911-12, revenue was £7,623 and expenditures £15,679. Ibid, p. 60. ↩

- Hosea B. Morse, The Trade and Administration of China (Shanghai:1921), p. 449. ↩

- Anonymous, “Wei-hai-wei: Its Value as a Naval Station”, Blackwood’s Magazine, June 1899. In Langer, The Diplomacy of Imperialism, p. 479. During the First Sino-Japanese War, Japanese forces captured the majority of the land-based fortifications and quickly turned the guns on the Chinese Beiyang Fleet in the harbour. Piotr Olender, Sino-Japanese Naval War, 1894-1895 (Petersfield: 2014), pp. 124-125. ↩

- Ian Nish argues that Weihaiwei “was taken in disregard of naval views at all levels.” Ian Nish, “The Royal Navy and the Taking of Weihaiwei, 1898-1905”, The Collected Writings of Ian Nish (Tokyo: 2001), Part II, pp. 72-87. ↩

- Convention between the United Kingdom and China, Respecting an Extension of Hong Kong Territory, 09 June 1898. ↩

- T. G. Otte, “‘Wee-ah-wee’?: Britain at Weihaiwei, 1898-1930″, British Naval Strategy East of Suez 1900-2000, (ed.) Greg Kennedy (London: 2005), pp. 4-34. ↩

- At best, and only after significant investment and infrastructure improvements, Weihaiwei could act as a forward coaling station and logistic point for Royal Navy raids or amphibious landings in and around the Gulf of Tchili. Ibid, p. 4-34. ↩

- Although a line was eventually established following the Boxer Rebellion, this British-controlled line began at the international station in Shanghai, and did not directly run from Hong Kong. Paul Kennedy, “Imperial Cable Communications and Strategy, 1870-1914”, in The War Plans of the Great Powers, 1880-1914, (ed.) Paul Kennedy, (New York: 2014), pp. 75-98. ↩

- Appleton, The Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events – 1902 (New York: 1903), Vol. 42, p. 325. ↩

- Appleton, The Annual Cyclopaedia, p. 325. ↩

- John Robert Seeley, The Expansion of England: Two Course of Lectures (London: 1883), p. 8. ↩

- “Wer mit Ungeheuern kämpft …zum Ungeheuer wird.” Friedrich Nietzsche, Jenseits von Gut und Böse (Leipzig: 1886), No. 146. ↩