Hans Christian Bjerg

Independent Historian, Author, and Lecturer

Readers of American and Danish history have considered the American purchase of the former Danish West Indies, The Virgin Islands, in 1916-17, as an isolated political event with a short previous history. Danish historians usually explain the sale to the US as mostly due to financial reasons. Denmark acquired, as colonies, the islands, St. Thomas, St. Croix and St. John in 1671, 1718 and 1733 respectively. From the late nineteenth century, Denmark considered maintaining the colonies a losing proposition. The disadvantages of possessing the islands were, before the 1860s, discussed occasionally in Danish political circles without any declared solution.

In 2017 Danish media marked the centenary of the sale. In this connection it was remarkable that two facts about the sale didn’t seem to be generally known. Firstly, that the process of the sale actually was going on for fifty years before the sale in 1917. Secondly, that the US naval strategy concerning the Caribbean Sea played a substantial role in the American interest in the islands. The purpose of this paper is to draw attention on both sides of the Atlantic to these facts.

In fact, the American interests in the islands, especially St. Thomas with its splendid harbor, began near the end of the 1860s. 1 After the Civil War it was time to consider the strategic conditions of the US. Secretary of State W. H. Seward focused both on annexing Mexico and on a possible American expansion into the Caribbean. Seward received a message from the American minister in Copenhagen expressing concern about the possibility the Danish West Indies would be included in the negotiations between Prussia and Austria after the defeat of Denmark in the war 1864. A Prussian or an Austrian possession of the Danish islands could be problematic from an American point of view. 2

In January 1865, Seward contacted the Danish Minister to the US, General W. R. Raasløff, who wrote to the Danish government about an American acquisition of the Danish islands. The Danish government was at first surprised by the enquiry, but eventually became willing to discuss it. The Danes stipulated the clear precondition that the two great European powers, Great Britain and France, would accept the sale 3.

From the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Danes were dissatisfied with their West Indies colonies. The three islands had become an economic burden instead of a profitable possession. As early as 1846, politicians discussed the possibility of selling the islands. The emancipation of the slaves on the islands in 1848 made the possibility of a sale even more appealing.

In a report dated 1865, Seward’s thoughts about the Caribbean found support from the US Navy. 4 One of the lessons of the Civil War at sea was the necessity of having bases to secure the supplies of coal. The report mentioned that the Danish islands with the excellent harbor of St. Thomas would be that kind of base covering the Caribbean Sea. Vice Admiral David Dixon Porter procured charts and hydrographic descriptions of the islands to use in further planning.

Talks between the US and Denmark went on for half a year. With the fall of the French-backed Second Mexican Empire and the restored Mexican Republic Seward took up the case again in 1866. Raasløff supported Seward’s initiative. Therefore, he went to Denmark to promote the idea among Danish politicians.

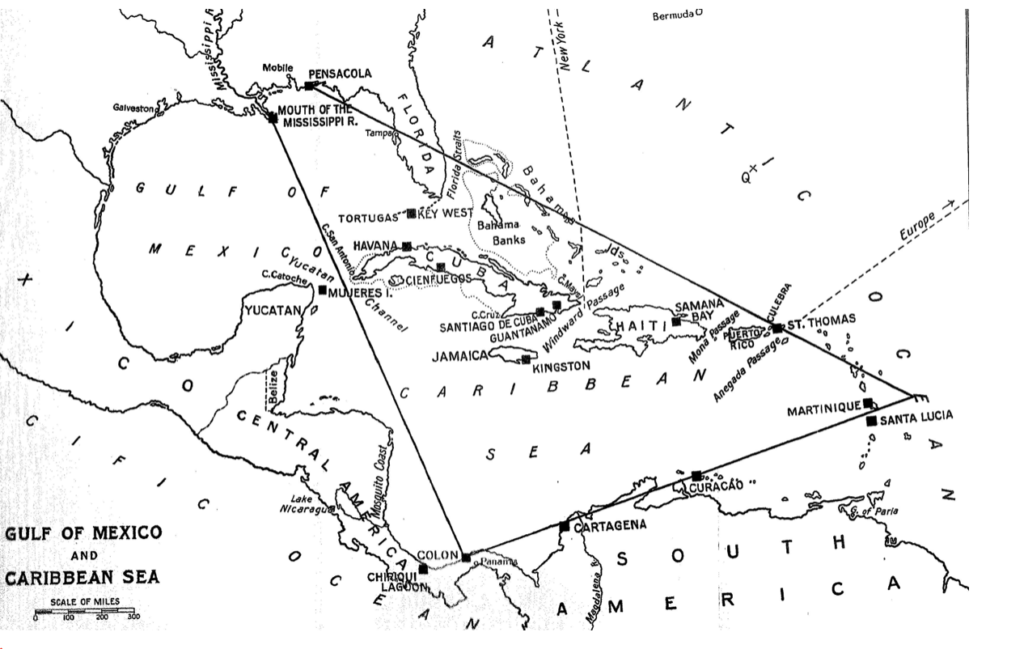

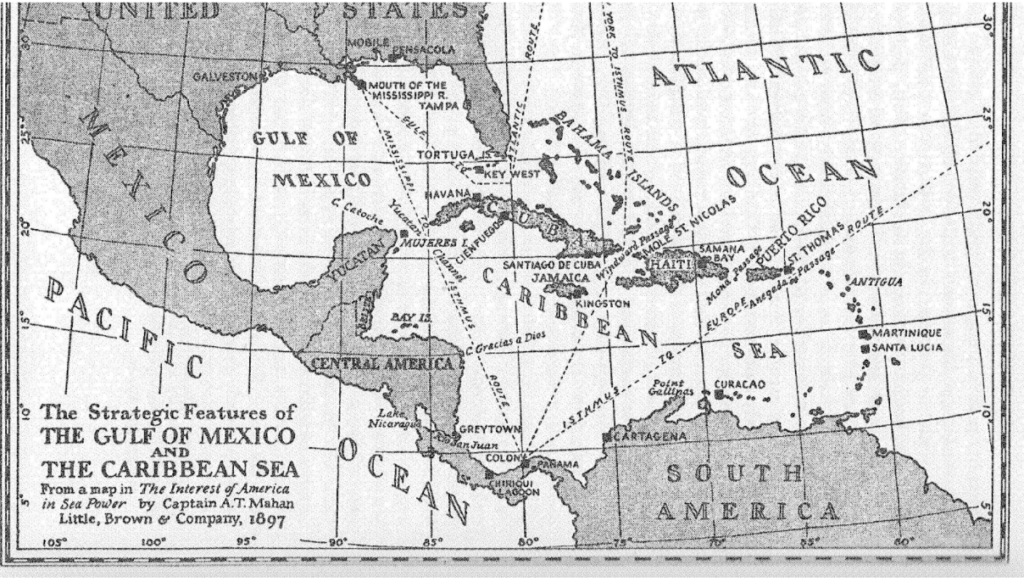

Historians differ as to who first advocated US possession of the Danish West Indies, but it is without question that Seward was the prime mover and that US efforts to acquire the islands were based on naval strategic interests. Figure 1 shows the strategic importance of the harbor of St. Thomas. Raasløf’s mission in Denmark succeeded. From November 1865, the Danish cabinet was ready to negotiate the sale of the islands. For the Danes, the decision primarily was an economic one.

The negotiations resulted in a treaty between the US and Denmark dated October, 24, 1867. In compliance with the treaty, the US purchased the three isles of the Danish West Indies for $7,500,000 in gold. The condition from the Danish side was that a majority of the inhabitants, by a referendum, accepted the purchase. The referendum was carried out in January 1868. At that time only around 1000 islanders had the right to vote, and they supported the sale nearly unanimously. The Danish Parliament, the Folketinget, ratified the treaty on January 28, 1868.

But the expected American ratification never took place. In 1867 the US purchased Alaska from Russia. The purchase caused some political problems and the situation was apparently one of the reasons why the political support for purchasing the Danish isles disappeared. It became hard work for Seward and Raasløff to maintain public and political interest in the purchase.

Hoping to sway public opinion, Seward and Raasløff asked Admiral David Porter to write a memorandum describing the strategic advantages of the purchase. In a memorandum dated November 6, 1867 Admiral Porter wrote the following about the island of St. Thomas:

[It}… could be defended easily as it was a small Gibraltar in itself……in the event of war with an European power, the United States would be at a disadvantage without a naval depot.” [St. Thomas]…is the most prominent position in the West Indies as a naval and commercial station. … It is situated … right in the track of all vessels coming from Europe .. and the Pacific Ocean, bound to the West India Islands or to the United States….It is a central point from which any or all of the West India islands can be assailed while it is impervious to attack from landing parties, and can be fortified to any extent…[It] ”…has the best harbor in the West Indies and no other harbor is better fitted than St. Thomas for a naval station .. In fine, I think St. Thomas is the keystone to the arch of the West Indies: It commands them all. 5

On the other hand, according to the opponents of the treaty, a naval station on St. Thomas would be the target for the first attack from an enemy in Europe. 6

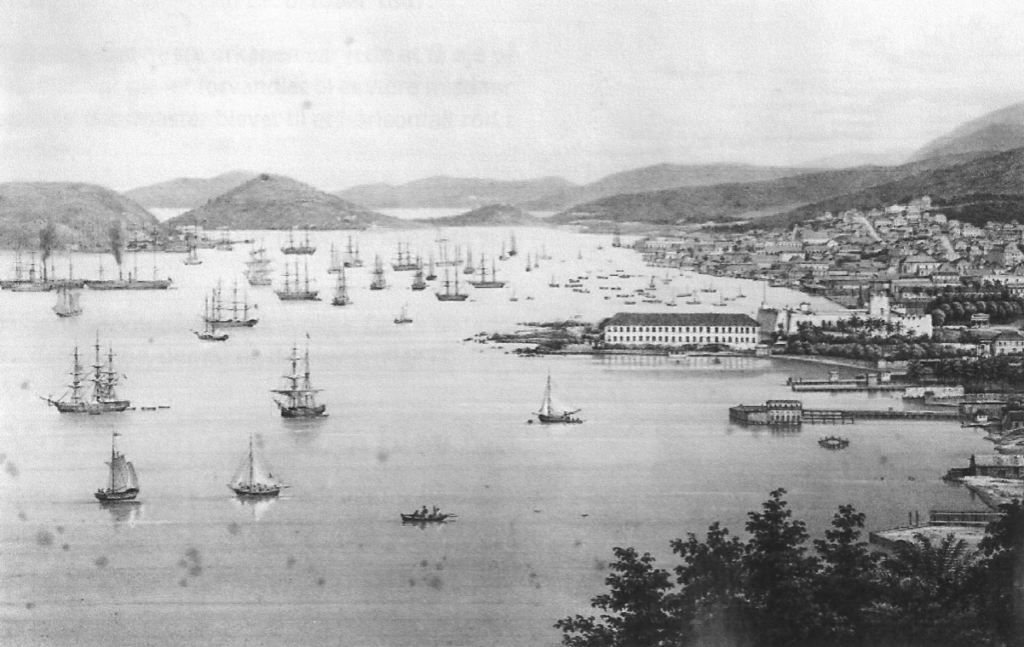

In connection with the discussions about the purchase, a Congressional delegation visited St. Thomas in November 1867. On October, 29 in the same year, a destructive hurricane had hit the area. Therefore, when the delegation arrived at St. Thomas, the harbor was in a very bad condition. Furthermore, during the visit, the isles were hit by a tsunami that caused further destruction. Without any doubt, these events had a negative effect on the politicians in their attitude toward the purchase.

In September 1867 Admiral David Farragut, commanding an American fleet, visited Copenhagen, where he received a warm welcome. The visit apparently fulfilled a request from Raasløff who at that time was Minister of War in, Denmark. Again, Raasløff was promoting the sale of the Danish West Indies. 7

Congress postponed ratification of the treaty and dropped the matter in 1870. Raasløff tried in vain to the very last, along with those American politicians who were in favor of the treaty, to garner political support for ratification. Raasløf hired an author named James Parton to disseminate arguments for an American agreement. 8 The pamphlet made the point that the United States was “bound in honor” to enter the treaty. Furthermore Raasløf and his supporters also asked Captain Gustavus U. Fox, former Assistant Secretary of the Navy Department, to formulate a memorandum on the importance of a US naval station on St. Thomas. On February, 27, 1869 Fox sent a long memorandum in which he reviewed every advantage the US could derive from the treaty. 9 He wrote, in part:

The harbor of St. Thomas is…one of the best in the West Indies, admirable for naval purposes, and fully equal to all the requirements of commerce of those seas…In future wars steam power can only be used successfully in the enemy’s commerce. Therefore it is patent that the nations having naval depots and surplus coal will occupy a commanding [role] in a maritime struggle.

However, all such lobbying in the United States was in vain.

In Denmark the US Congress’ decision to forego the treaty caused a political crisis. The expectations of an American ratification were high. As a consequence of the US decision, the Danish Cabinet was dismissed. Many people in Demark and the West Indies were disappointed.

During the 1870s, several rumors emerged that the new German Empire was interested in an exchange of Schleswig for the Danish West Indies. The Danish Government strongly denied that these negotiations between Copenhagen and Berlin were going on. Nevertheless, the possibility of a German naval base in the Caribbean concerned both the US and the European powers as well.

In fact, the offer to the Americans was still discussed in Denmark through the 1870s. An uprising in 1878 among the black inhabitants of the Danish West Indies strongly stoked the desire of many Danes to quit the islands in one way or another.

However, we now know that around 1885 the German Naval Command considered the possibility of acquiring a naval base in the Caribbean. Among other locations, the Germans were focused on St. Thomas. In fact, several German ships enroute to South America were ordered to pass St. Thomas in order to investigate the harbor and its surroundings. However, the Germans seemed to give up the idea in 1890. 10

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 stimulated US plans to construct a canal through the isthmus of Panama to connect the Pacific with the Atlantic. From 1890 onward, the US took serious steps to realize this project. Therefore, a new look at the American strategy in the Caribbean became necessary. For the same reason, the German Naval Command again began to make plans for a naval base in the area.

In 1891, the Danish government suggested to President Harrison’s Secretary of State, James G. Blaine of selling the islands to the United States. But Blaine considered the islands too small to be of strategic or commercial interest. He did state the Danish isles were “destined to become ours but among the last of the West Indies should be taken.” However, Blaines successor as Secretary of State, John W. Foster, was more favorably disposed to the idea of acquiring the islands. 11

The next step was to send a new enquiry to Copenhagen about an acquisition of the isles. At first there was no political reaction to the enquiry, but after 1892, Denmark began to show renewed interest in the case.

As a consequence, prominent American publicists began to discuss the strategic challenges to the US and its position in the Caribbean Sea, especially if a canal across the Isthmus of Panama became a reality. The most distinguished of these publicists was Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, USN, who, after the 1890 publication of his book about the influence of sea power upon history, became a well-known naval analyst. In an article entitled, “The Isthmus and Sea Power” in 1893, he discussed the many dangers that would threaten an American-built isthmus canal. 12 He underscored, in this connection, the many strategic positions in the area which belonged to others, especially European powers, and as a consequence, could present a problem for the US in the future.

Mahan argued in 1897 13 that Samana Bay, the Mona Passage between Santo Domingo and Puerto Rico, and St. Thomas by the Anegada Passage were positions with high strategic priority. Both passages represented principal routes into the Caribbean Sea. ”St. Thomas”, wrote Mahan, “better than any other, represents the course from Europe to the Isthmus.” 14 Mahan’s articles about these strategic problems were published in his book, The Interest of America in Sea Power, in 1898.

It is well known that a close relationship existed between the then Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt and Mahan from the beginning of the 1890s. In fact, the acquisition of the Danish West Indies was a subject in their correspondence and talks. About this matter, Roosevelt wrote to Mahan in 1897 that, “The expulsion of Spain [from Cuba], accompanied by the purchase of the Danish Islands, would serve notice of the real position of the United States in Caribbean affairs.” 15

In connection with renewed American interest to enter into a treaty with Denmark, Roosevelt called upon Mahan to provide expert testimony pertaining to the strategic value of St. Thomas. Mahan stated that St. Thomas was “one of the greatest strategic points in the West Indies.” 16

The strategic considerations that motivated the US to enter the Spanish-American War in 1898 were the same ones that drove the effort to purchase the Danish isles; namely to secure the eastern entrance to the Panama Canal. The War in 1898 temporarily blocked the American efforts concerning Danish West Indies. But after the war the case was in focus again.

Before the peace treaty with Spain was settled, Mahan wrote to the Senator Henry Cabot Lodge about matters in the Caribbean” 17

Assuming, as seems pretty certain, that the United States is to acquire Puerto Rico, may I suggest the advisability as a corollary to this step, after the peace is signed, the purchase of St. Thomas. Puerto Rico and these small Danish islands form a compact strategic entity, yielding mutual support. St. Cruz is immaterial…the harbor of St. Maria is very fine … the port of St. Thomas, reasonably fortified, would be a distinct addition to the military strength of Puerto Rico, considered as a naval base.

In 1900, negotiations between Denmark and the US began anew. This time the US was very keen on the cession. The two nations signed a treaty on January, 24, 1902, and Congress ratified it afterwards. However, the efforts and discussions in Denmark during the 1890s against a cession did have some impact, and it was very clear that the attitude in favor of the sale had decreased generally among the Danes. Now, many Danes wanted to give the isles a better future as part of Denmark. The discussion between the two Danish factions grew intense and heated. Therefore, in Denmark, the treaty was ratified by the Folketinget but not by the Landstinget, the second chamber of Danish government. Thus, the treaty was stalled again.

In 1905, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge tried to draw attention to another purchase. This time the proposal included the acquisition of Greenland. Lodge’s efforts were in vain. Apparently, in the following decades, the proposal drew no political attention interest.

The Panama Canal opened on August 15, 1914. The War in Europe broke out shortly before this important event, and the US worried that Germany might occupy Denmark and would take the Danish West Indies in possession and place a naval base in the harbor of St. Thomas. The US government entreated the Danes to seriously ratify the treaty.

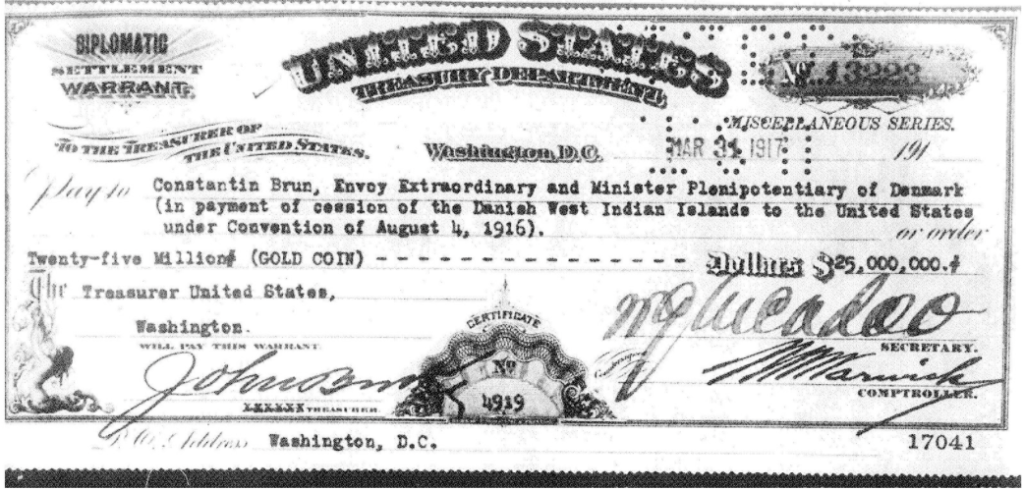

This time the treaty was settled. The Danish government accepted, and the Folketinget and Landstinget did the same. The decision was confirmed by a referendum in Denmark afterwards. The convention was signed August, 4, 1916 and was proclaimed in January, 25, 1917. The price was $25,000,000 in gold. Additionally, the US signed a declaration to Denmark that the:

Secretary of State of the United States of America, duly authorized by his Government, has the honor to declare that the Government of the United States of America will not object to the Danish Government extending their political and economic interests to the whole of Greenland.

In view of the Monroe Doctrine, this statement was a remarkable concession, still of importance today. The acquisition of the Danish West Indies (now the Virgin Islands) in 1917 completed, at last, negotiations that had taken fifty years to give the US Navy a strategic foothold in the Caribbean.

Figure 4 – The payment on 25 million dollars in gold from the United States of America to Denmark 1917

(Return to December 2021 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

- The main source for the history of the American purchase of the islands is Charles C. Tansill: The Purchase of the Danish West Indies (Cloucester, Mass: 1932, reprinted 1966). The Danish sale is described in two chapters: Friedlev Skrubbeltrang: Dansk Vestindien 1848-1880, pp.353-468, and Georg Nørregaard: Dansk Vestindien 1880-1917, pp. 469-542; Johannes Brøndsted (ed.) Vore Gamle Tropekolonier, Vol. II, 1953; A new but shorter description was published in Danmark og kolonierne, Vol. 2. (Vestindien, København, 2018). A recent survey is by Hans Christian Bjerg: ”Salget af de vestindiske øer. En langstrakt flådepoltisk affære”, in Tidsskrift for Søvæsen, 2017, pp. 158-163. ↩

- See Halfdan Koht, “The Origin of Seward’s Plan to Purchase the Danish West Indies,” in American Historical Review, Vol. 50, No.4 (October, 1944), pp. 762-67. ↩

- General Raasløff’s influential role in the 1860s on the question of the Danish West Indies is treated in Erik Overgaard Petersen, The Attempted Sale of the Danish West Indies to the United States of America, 1865-70 (Frankfurt : 1997). ↩

- Tansill p. 5. ↩

- Tansill p. 81. The memorandum was published as an article in the New York Times 14, December 1867. ↩

- An article in Merchant’s Magazine and Commercial Review, Vol. 58, 1868, pp.17-19. ↩

- James Eglinton Montgomery, Our Admiral’s Flag Aboard: The Cruise of Admiral D.G. Farragut commanding the European squadron in 1867-68 (New York: 1869), pp. 115-134; Tansill, pp.67-68. ↩

- James Parton, The Danish Islands, 1869. ↩

- Tansill, p. 120. ↩

- Göran Henriksen: “Denne tyska Marinen och Danska Västindien 1885-1890,” in Krigshistorisk Tidsskrift (Journal of Military History), 1976, pp. 3-25. (An article in Swedish language published in a Danish journal). ↩

- William E. Livezey, Mahan on Sea Power, Second Edition (University of Oklahoma Press: 1981), pp. 107-108. ↩

- Published in Atlantic Monthly, September 1893, and later published in Mahan, The Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future, (1898); See also Tansill, p. 199. and Livezey, p. 106f. ↩

- Mahan, “Strategic Features of the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, October 1897. ↩

- Mahan, ”The Interest of America in Seapower,” pp.260-61; Tansill, p. 210. ↩

- Livezey, p.120f. ↩

- Livezey, p. 153. ↩

- Livezey, p. 150ff. ↩