By Howard J. Fuller

University of Wolverhampton

Quite simply, the Warrior altered the course of the American Civil War.

This isn’t something that’s made its way into the history books—literally thousands of them, more and more, when it comes to the great ‘turning point’ in American (and possibly world) history, as it’s often described. 1 For while the Warrior is still stately and afloat after 150 years, and many across the Atlantic now commemorate the Civil War’s own sesquicentennial, the stories of both, together, have been kept rigidly compartmentalized. There is American history, or there is British history; Civil War or Imperial history; diplomatic or naval history. The lines rarely cross, still. Should we continue to blame the ocean?

Yet the assertion above is understandably obscure because, on the surface at least, it’s entirely counterfactual. Great Britain never openly intervened in the American conflict—despite many close calls and temptations. The Royal Navy did not unleash its mighty ironclad champion upon the (presumably) Northern States. Nor did the Union Navy even attempt to challenge Britain’s mastery of the seas which the Warrior represented; instead, its own frontrunner, the U.S.S. Monitor, was little more than a gunboat and was herself finally mastered by the sea, on 31 December, 1862, taking down a quarter of her crew. And while President Abraham Lincoln mourned the loss, neither he nor the Department of the Navy pined for an equally gigantic, American Warrior to replace her. The ‘War Between the States’ was predominantly a brown-water affair whose chief strategic lines of communication, supply and invasion were along a generally shallow, treacherous coastline, and up and down winding riverways. As naval historian Donald Canney has argued, in the wider context of the Industrial Revolution as well as the turbulent scene in America, “the reflection of these world technological developments was distorted: capital ships such as the revolutionary British Warrior of 1860 did not play a significant part.” 2

So how did something which didn’t happen make a decisive impact upon everything else? This is also one of the comparatively unspoken, and difficult, truths of history. Andrew Lambert’s study of H.M.S. Warrior offers the point-blank sobriquet of ‘Victoria’s Ironclad Deterrent’. Here it doesn’t matter the battles actually fought but those prevented—in a rational calculation of opposing strengths and weaknesses as a recurring feature of modern international relations. It’s then left to the historian (American, British, military, political) to reconstruct from a variety of artefacts, clues and sources a complex causal chain of events.

—————————————————-

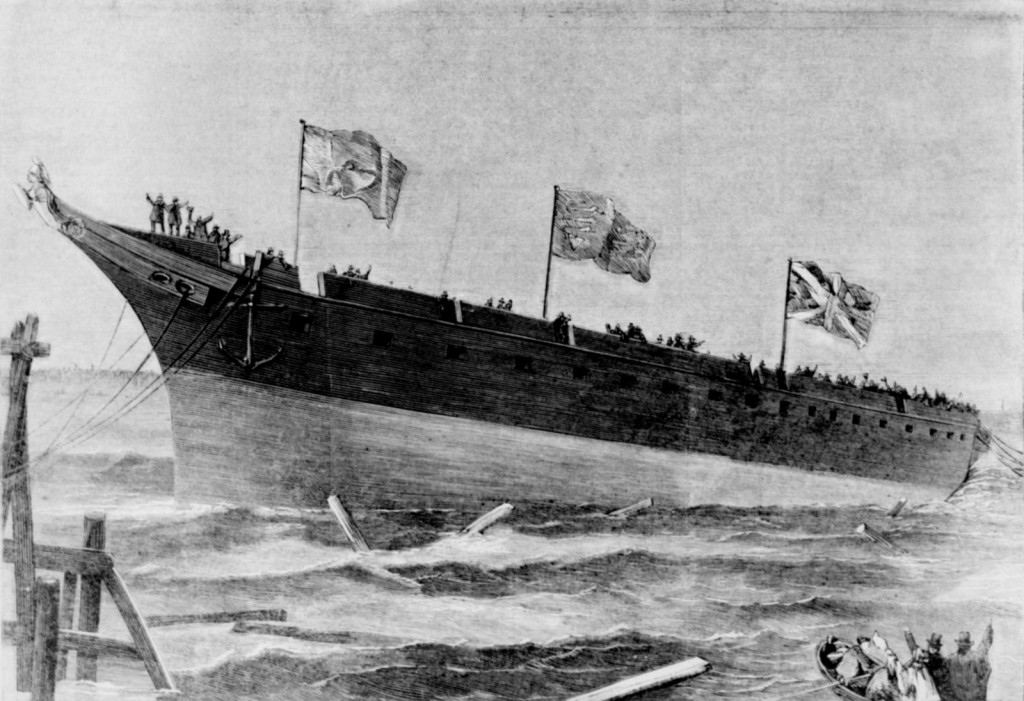

Our story begins in the press. The first printed descriptions of the Warrior were soon complimented by those amazing woodcut illustrations of Victorian greats like The Illustrated London News. Circulation took weeks, not minutes like today, to reach the far corners of the world by ship; but the news was nonetheless global and perhaps even more valuable—because it was a precious commodity—than now. As Lincoln exclaimed to famed Times correspondent William Howard Russell, “The London Times is one of the greatest powers in the world—in fact I don’t know anything which has much more power—except perhaps the Mississippi.” 3 1860 was a peculiar junction in the evolution of the ‘media’. Telegraph technology was available, though not quite yet on a trans-oceanic or continental scale. Likewise, while photography had advanced from the daguerreotype to the tintype process it did not mass-produce well. This left accounts of Britain’s revolutionary new iron war-behemoth, next to recent constructions like the Great Eastern, at the discretion of artists on the one hand and the imagination of readers on the other. In the mid-Victorian era bigger was better; a hallmark of the Great Exhibition of 1851. Anything seemed possible, and when it came to men-of-war, it seemed almost fitting to unleash a bold new design-concept, as the Industrial Revolution reached its zenith, which could literally traverse the wide breadth of the Queen’s empire, in every corner of the globe. The Warrior could go anywhere. She was more than a cruiser, even more than a battleship in her own way; she was Noah’s Ark, the dawn of a new world of British naval supremacy. Everything rested upon her long iron beams and steady Penn trunk engines. As such, when the weekly graphics depicted her under construction she was already larger-than-life, already a legend in the making. In fact it seems the artists settled on a distortion of some 25% bigger than reality (either that, or the Warrior in these illustrations was built by dwarves.) 4

It didn’t matter that the proportions were all wrong. The Admiralty knew better, so did Thames Shipbuilding. What was important is that the popular conception of Warrior mirificus was not only imbedded in the mind’s-eye of Britannia, it was exported worldwide. Thus, when Scientific American relayed the news to its many lay and professional subscribers, it immediately attached the warning cry that “owing to our inefficient navy, we cannot afford sufficient protection to American citizens engaged in commerce in various parts of the world… At present we have not a single first class war steamer—one that can compete with the most recently built French and British ones…we mean the iron-cased war wolves.” Warrior had slipped into the Thames less than two weeks before, and already the alarm had gone up across the Atlantic that England’s newfound strength (or “terrific power”) must suddenly imply everyone else’s weakness. Of course this was wrong; the U.S. Navy had yet to devise any cheap and easy response that realistically countered the threat of war with a maritime titan. Writing from the newly-built but sail-only sloop U.S.S. Constellation in 1856, one officer urged ordnance expert and gun designer Commander John A. Dahlgren to rearm ships with short-range guns only—for fighting “night actions, always”. Now, America’s engineering intelligentsia shrieked how “a whole fleet of unplated vessels are completely at the mercy of one of the new iron-plated ships”, while the much more popular Harper’s Weekly headlined the “Revolution in Naval Warfare” with a half-page reprint of a British woodcut of the Warrior’s launch. 5

In the midst of this crisis of confidence, Abraham Lincoln, the new Republican Party candidate, was elected President, triggering the great Secession Crisis of the United States. Within three months (and before Lincoln even took office) seven of these formed their own ‘Confederacy’. Here, neither frantic political party negotiations nor Lincoln’s own considerable bargaining skills proved capable of stemming an avalanche generations in the making. Civil war was imminent. North America might not be a matter of ‘Manifest Destiny’ after all; a continental-scale power under one government. Instead, there could be several, rival republics, some free-soil, some slave-holding—and all perennially armed. Not only would America become like Europe, the Great Powers themselves would surely get involved. The nature of the new global economy by the mid-19th century meant that a war over the fate of North America affected everyone’s ‘interests’. The trans-Atlantic trading relationship was the most lucrative in the world, in history even, and any disruption of that would hardly be offset by an appeal to American nationalism or ‘Union’ (the North) over Southern independence. When the decision to blockade the entire rebel Confederate coastline finally issued from the White House, on 19 April, 1861, everyone in the Northern States knew who would be affected as much as the South: Great Britain. And while Queen Victoria’s own Proclamation of Neutrality angered many confused and embarrassed Yankees who expected moral support if nothing else, the blockade would take months, if not years, to be considered legally ‘effective’ as far as foreign powers were concerned. British recognition of the Confederate States would meanwhile “be British intervention, to create within our territory a hostile state by overthrowing this Republic itself,” wrote Secretary of State William H. Seward. And intervention would mean a world war “between the European and the American branches of the British race.” 6

It did not take long—if it was not simultaneous—for the dread spectre of British intervention in the American Civil War to assume the shape of HMS Warrior. And if the thought of this one warship, as a national icon of British naval and imperial power, haunted Lincoln’s cabinet (and gave heart to that of Confederate President Jefferson Davis 7 ), it also gave rise to the Union’s great response—in the form of the U.S.S. Monitor. Indeed, it is difficult to see how the Monitor would have been born without the Warrior’s influence.

Years before, Swedish-born inventor-engineer John Ericsson had devised his ‘sub-aquatic system of warfare’ for the Allied powers during the Crimean War. Though the Russian navy was largely bottled up before St. Petersburg, neither the British nor French were confident of their ability to overcome the combined defences of Cronstadt, guarding the seaward approach to the enemy capital. Stone forts were still stronger than wooden hulls. Ericsson’s plan called for a specialized steamer, screw-propelled and wholly armoured, with only a shallow raft mounting a revolving iron dome visible above the waterline. Inside this “impregnable globe” would be guns of the heaviest known calibre and capable of inflicting singular knock-out blows. Armed with such a vessel, Ericsson suggested to Emperor Napoleon III, gauntlets could be run with relative safety, and “A fleet at anchor might be fired and put in a sinking condition before enabled to get under way.” Alas for steam blockships—and “for the ‘wooden walls that formerly ruled the waves!’ ” 8 The French, however, bombarded with a stream of plans (some more ill-informed than others) of how to decisively ‘win the war in a single day’, kept the idea of iron armour plating and steam propulsion generally and rejected John Ericsson specifically. Under the guidance of their own Ministry of Marine, shallow-drafted ‘batteries’ were constructed which could deliver a conventional broadside at fairly close quarters against shore fortifications. At the very least these might suppress counter-fire while a general bombardment rattled the defenders and troop landings took them from the rear. Iron might thus neutralize granite. At Kinburn (17 October, 1855) the results were remarkable; the French armoured batteries took amazing punishment yet performed well. Britain was building iron batteries of her own, along with a whole new Brown Water flotilla of gunboats and mortar vessels which suddenly shifted the seat of war back to the Baltic, even as Sevastopol finally fell to the bitter Allied siege in the Crimea. Ericsson accordingly tucked his proposal away and returned to other ventures. On 29 August, 1861 he was drafting a letter to President Lincoln ‘offering his services’.

Now the goal was rooting out Confederate warships guarded by land batteries—particularly the captured remains of the steam-frigate Merrimack at Norfolk, Virginia, which the rebels were known to be converting into a formidable iron-plated monster. Ericsson sought “no emolument of any kind”; he was rich enough on various engine patents and seems to have been caught up in the patriotic tide sweeping the North after the humiliating defeat at 1st Bull Run (21 July, 1861). He was also canny enough to mention in closing the “now well-established fact that steel clad vessels” could not be stopped by forts, and that New York City was “quite at the mercy of such intruders, and may at any moment be laid in ruins…” If Britain or France ever did challenge the Union blockade and enter the war, Ericsson reminded Lincoln, only his weapons-system held the key to “crushing the sides” of their ironclads “regardless of Armstrong guns” 9 .

American Civil War history leaves this letter out; indeed Ericsson never sent it. Perhaps he sensed that it would be lost in another flood of half-baked ideas from mostly under-qualified engineers and inexperienced inventors, patriotic or not. Nor could he go the customary route of pitching it to navy professionals; he was in the midst of a long-standing feud with many of them for the disastrous explosion of the ‘Peacemaker’ gun aboard the screw-propelled warship which he had designed and built in 1843, the U.S.S. Princeton. Instead, as the well-told story goes, he was drawn into the public bids for ironclad steamers (which Congress had advertised for earlier that August, 1861) by Cornelius Bushnell—who wanted the famed engineer to double-check the stability of his own submission. While performing the necessary calculations, Ericsson pulled out the dusty cardboard mock-up of his strange cupola vessel. It was nowhere near as predictable as Bushnell’s soon-to-be U.S.S. Galena. But his colleague immediately recognised a potential alternative to broadside-ironclads, and a deadly response to European powers. On Ericsson’s behalf he presented the model personally to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and then his Assistant, Gustavus Vasa Fox, announcing the President “need not further worry about foreign interference; I [have] discovered the means of perfect protection.” Lincoln himself later whimsically added to the Ironclad Board reviewing Ericsson’s plans, “All I have to say is what the girl said when she put her foot into the stocking: ‘It strikes me there’s something in it.’ ” 10

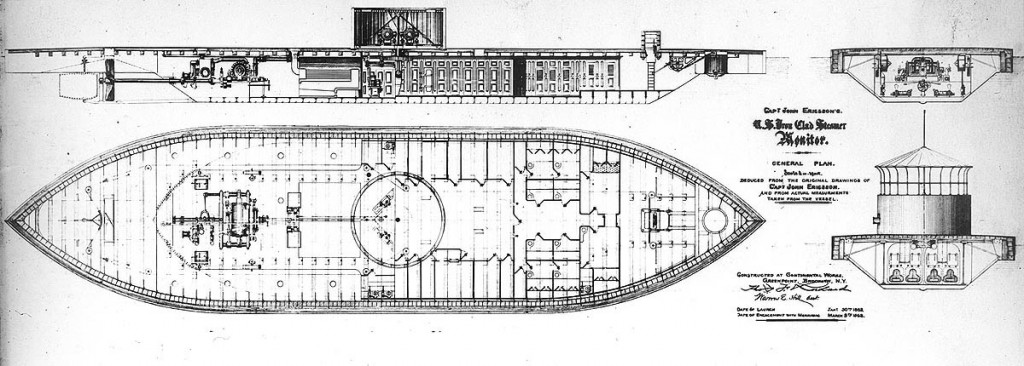

USS Monitor general plan published in 1862, showing the ship’s inboard profile, plan view below the upper deck and hull cross sections through the engine and boiler spaces. NHHC image NH 50954.

If this extraordinary man-of-war was first approved and contracted for in the two-tone shadow of a threat, one Confederate and the other European, then it was certainly in the harsh light of the Trent Affair—within a fortnight of her keel being laid—that she actually found a name. Nothing roused Britannia’s ire more than the brazen capture of two Southern emissaries aboard the British packet steamer by a Yankee cruiser, on 8 November, 1861. Anglo-American tensions were already at the breaking point since the Civil War began; the blockade, the Queen’s Neutrality, the highly protectionist Morrill Tariff, and the apparently open-ended duration of the conflict itself had sparked an increasingly acrimonious press war with Columbia even harsher than that of Northand South. Both English-speaking halves of the mid-Victorian era accused the other of arrogance and ignorance and both were probably right.

Only one side, though, had the muscle to ram home its point at that precise moment. This was a brutal lesson which Lincoln painfully recognised by Christmas, when he quietly released the two Confederates back into British custody. Far less subtle was Harper’s Weekly in its cartoon of 11 January, 1862, which depicted John Bull’s menacing new henchman wearing a suit of armour, and labelled ‘Warrior’—a connotation Lord Palmerston fully supported even before the crisis erupted. In a letter earlier that summer to the First Lord of the Admiralty, the Duke of Somerset, the Prime Minister urged that both the Warrior and her sister-ship Black Prince be sent to the American station as soon as they were completed: “Their going could produce no bad Impression here, and depend upon it as to Impression in the United States the Yankees will be violent and threatening in Proportion to our local weakness and civil and pacific in Proportion to our increasing local strength.” 11 The unintended side-effect of all this realpolitik and ‘deterrence’ was how it sharply focused the Union’s need for an ironclad defender of its own. “The impregnable and aggressive character of this structure”, wrote Ericsson immediately following the Trent Affair, “will admonish the leaders of the Southern Rebellion that the batteries on the banks of their rivers will no longer present barriers to the entrance of the Union forces”:

The iron-clad intruder will thus prove a severe monitor to those leaders.

But there are other leaders who will also be startled and admonished by the booming of the guns from the impregnable iron turret: “Downing Street” will hardly view with indifference this last “Yankee notion,” this monitor. To the Lords of the Admiralty the new craft will be a monitor, suggesting doubts as to the propriety of completing those four steel ships at three and a half million apiece.

On these and many similar grounds, I propose to name the new battery Monitor. 12

Here too, the history books tend to overlook the role the British Warrior played in not only making the American Monitor but popularising that whole class of warship until it nearly lost the war for the Northern states. In his seminal 1933 work, The Introduction of the Ironclad Warship, James Baxter traces the overriding influence of Ericsson’s original ‘Monitor’ prototype in the fateful, decision-making days between August and December, 1861—three months before that warship duelled the Confederate Virginia (the Merrimack) to a standstill at Hampton Roads, Virginia (9 March, 1862). Not only did the U.S. Navy Department—and Gustavus Fox in particular—prefer traditional ocean-going frigates on the general plan of Britain’s Warrior, if not the French Gloire, but the Bureau of Ship Construction & Repair had its own scheme of a multi-‘cupola’ vessel in the works. Both ideas, however, required solid 4½-inch armour plating which had to be largely manufactured abroad and imported. Had the Trent Crisis not occurred during this interval, the Union’s ironclad navy during the Civil War might very well have had a different face, with a different outcome to the entire conflict.

Furthermore, it took the much more ominous threat at this time of a potential duel with the Warrior, or a similar vessel illicitly contracted for use by the Confederate States Navy, to underscore the need for a light-draft, ironclad-killing ironclad with an emphasis on sheer impregnability and hard-hitting ‘monster’ guns—even at the direct expense of long-range sea-keeping, or cruising. Neither the Bureau’s own turret vessel or indeed any broadside-armed ironclad conceived of, under construction or actually launched in the world by the beginning of 1862 was as purpose-driven (if not single-minded) as the ‘Ericsson Battery’, as it was being called in the Northern press reports. The Warrior helped give the Monitor focus, and helped the latter swerve Union naval policy towards counter-deterrence—or coastal defence—first, and coastal assault—against the Confederacy—second. As Baxter recounts, Ericsson had already provided the Secretary of the Navy with plans for an improved monitor (the Passaic-class), with thicker turret armour and to be armed with even larger smoothbores; 15-inch of 21 tons, and firing a solid shot of 450lbs., rather than the 11-inch Dahlgrens fitting on his battery in New York. Shortly afterwards, Union agents confirmed that “both the Home Office and the Admiralty, with a most delicate sense of the obligations of neutrality, which the British government did not invariably exhibit during this war, deemed the manufacture of armor plates for sale to the United States government illegal.” 13

The problem was that the Monitor, like all early ironclads, was expected to fulfil a variety of frequently ‘urgent’ yet conflicting roles. In her strict capacity as a man-of-war she successfully dominated American coastal waters, starting with the Battle of Hampton Roads. When news of this action reached Britain, in the spring of 1862, a wave of popular critical reaction swept over Whitehall. It was only by pointing out the Brown Water-limits of the Monitor, as a continental gunboat fighting in a civil war and not as a Blue Water-cruiser patrolling a global, maritime empire, that Palmerston in the Commons, and Somerset in the House of Lords were able to defer any serious lack of public confidence in national defence by sea. Privately, Old Pam had his misgivings about the “Pasteboard ends” of the Warrior being “knocked to shivers: the underwater compartments filled with water, everything above waterline smashed to Fragments; the Centre Box laying like a dog on the water, sunk several feet below the water line.” During the Trent Crisis “the only Danger” he could conceive from the Union Navy “would arise from their having armed their vessels with very heavy guns throwing large Shells, and being therefore Gun for Gun probably stronger than ours of similar classes.” The Warrior and her sisters he assumed would “checkmate” these. 14 Now the Monitor altered the equation again. “Only think of our position”, warned the Foreign Secretary, Lord Russell, to Palmerston, “if in case of the Yankees turning upon us they should by means of iron ships they should renew the triumphs they achieved in 1812-13 by means of superior size and weight of metal.” 15 But neither was the British government about to invest in ironclad ‘batteries’ rather than the controversial new harbour and coastal fortifications Palmerston had already insisted upon to neutralise the growing pretensions of Napoleon III. Given their littoral limits—particularly their limited coal bunkerage—monitors could hardly be expected to guard distant imperial frontiers either. 16

Thus, when talk turned to possible intervention, in the autumn of 1862 (following news of the Battle of Antietam on 17 September, and President Lincoln’s subsequent Proclamation of Emancipation to all the slaves in the Confederacy), the strategic problem of the Monitor and her sisters under construction in the North seriously complicated the idea of war with the United States. During the previous December, Britain was ready to single-handedly “iron the smile out of their face”, as expressed by Secretary of State for War Sir George Cornewall Lewis. By the following October, nothing less than a unified European front of five major Powers would be required, Russell finally admitted, to insure that Washington would not go through with its standing threat of war if Europe recognised the Confederacy. 17

The Northern press, as could be expected, took no end of pleasure from this reaction to the Monitor overseas. Scientific American reversed its previous insistence upon ocean-going Warriors and declared the Monitor more of the new ideal. “Practical men” in America saw revolving gun turrets “applied to any war vessel, no matter how large or fast she may be”; while “the designers and constructors of iron-clad vessels in England have committed a great mistake in building their frigates with too great a draft of water.” Harper’s Weekly depicted the Monitor literally lecturing foreign powers how to build proper ironclad warships, showing up Johnny Bull in the proverbial contest of toy boats on ponds, and forcing the British Lion to change its tune over possible intervention. 18 It seemed, in those golden days and weeks following her debut, that anything indeed was possible.

In fact, the Monitor was capable of achieving very little—especially against forts. On 15 May, 1862, she attempted to force her way up the James River and place the Confederate capital of Richmond under her guns. A handful of cannon on the river bluffs, offering plunging fire, combined with obstructions blocking the river, were enough to drive off the Monitor, and leave her companion ironclad—Bushnell’s Galena—riddled with holes and casualties. Yet despite her commanding officer’s misgivings, Fox insisted that the newer monitors, in sufficient numbers, might smash their way into even the most heavily-guarded ports of the South. Hotbeds of rebel defiance, namely Charleston, South Carolina, would then be left with the stark choice of surrender or bombardment. This might have worked, had not the Confederates recognised that mines (or ‘torpedoes’) combined with forts and obstructions, were often enough to out-scare the enemy in his terrible new engines-of-war. Even Ericsson had his doubts; he had never promised an iron ship which could out-gun a stone fort—or even an earthwork. Turret ships might deliver 15-inch guns through gauntlets and sink any enemy warship, armoured or not, which they encountered. But they were just as susceptible to underwater threats as the Warrior, and much more prone to sinking like a stone if actually damaged, having little reserve buoyancy.

USS New Ironsides (left) and USS Monadnock (1864-1874) (right foreground) Engraving published in “Harper’s Weekly”, 3 February 1866 as part of a larger print entitled “The Iron-clad Navy of the United States. Text printed below the image is in error concerning the date of New Ironsides’ launch, which actually took place on 10 May 1862. NHHC image NH 61431.

What the Union Navy actually needed in its combined operations against Charleston were more broadside-ironclads like the U.S.S. New Ironsides, drawing 16-feet of water, if not the Warrior, drawing 26. At the very least, a half a dozen iron-armoured steam-batteries like those employed by France during the Crimean War might have likewise overpowered forts Wagner, Moultrie and Sumter, while the channel obstructions were swept and Union firepower was finally brandished before the ‘Heart of Rebeldom’. 19 Then again, how the New Ironsides’ 11-inch Dahlgrens would have fared against the sloping 4½-inch armour of the Confederate ironclads lurking in the inner harbour was another matter. Soon the beleaguered city was laying down another ‘Ram’, the Columbia, to be armoured with 6-inches of plating. Perhaps this fateful, strategic dichotomy was best summed up by Union Rear-Admiral David Porter at the close of the Civil War, during the massive combined operations against Fort Fisher, North Carolina (23 December, 1864 – 15 January, 1865):

The [double-turret monitor] Monadnock is capable of crossing the ocean alone (when her compasses are once adjusted properly), and could destroy any vessel in the French or British navy, lay their towns under contribution, and return again (provided she could pick up coal) without fear of being followed. She could certainly clear any harbor on our coast of blockaders in case we were at war with a foreign power… Compared with the Ironsides, [the monitors’] fire is very slow, and not at all calculated to silence heavy batteries, which require a rapid and continuous fire to drive men from the guns; but they are famous coadjutors in a fight, and put in the heavy blows which tell on casemates and bombproofs. 20

Veteran ironclad Union Captain John Rodgers also felt that “the Monitor class and the Ironsides class are different weapons, each having peculiar advantages; both needed to an iron-clad navy, both needed in war”; while Rear-Admiral John Dahlgren, commanding the blockade squadron before Charleston, asked “What other style of vessel could the department have chosen? Certainly none that has been built by English or French naval authorities. The Warrior and her class are exceedingly powerful, but could not get within gunshot here.” 21

As a result, those Confederate ironclad-rams which ventured out to challenge monitors were routinely forced to retire or surrender within minutes. The London Times demurred that these examples were hardly comparable; rebel casemates employed laminated armour plates—though inclined at least 45° to the horizon—and the latest experimental Armstrong guns would have accomplished even more in less time. This was the crucial factor, as Punch satirised; for if the Civil War in America continued much longer, ‘Mrs. North’ was going to have to fire her ‘Attorney’, Mr. Lincoln, and “put the case into other hands” in the November 1864 presidential election. But these complaints were more directed to the Admiralty apparently dithering on the concept of a sea-going turret-ship in the first case, and to chastising stubborn Yankees in the second. At any rate, the American Army & Navy Journal responded that “those iron-clads which the Times has handled so severely, the Monitor Monadnock among the rest, are intended for coast and harbor defense. It is not proposed to send these vessels after the Bellerophons or Minotaurs, but at the same time it may not be prudent to send these unwieldy craft after them.” 22

The United States had clearly gotten over its initial anxiety of the Warrior. This was, the New York Herald proclaimed, the inevitable triumph of ‘Yankee Genius’. 23

The Civil War, however, continued anyway.

—————————————————-

This article has briefly described how the Warrior not only influenced decision-making in shipbuilding design and the formulation of naval policy abroad, but how those choices affected the conduct of battles, campaigns and even diplomacy. Following news of the Battle of Hampton Roads in London, the U.S. ambassador, Charles Francis Adams, wistfully observed:

In December we were told that we should be swept from the ocean in a moment, and all our ports would be taken. They do not talk so now. So far as this may have a good effect to secure peace on both sides it is good… 24

The Union’s historic response to the Warrior was indeed the Monitor, a weapons-platform concept far in advance of her contemporaries, including the idea of the man-of-war as nearly self-automated ‘machine’. For their part, British naval authorities were intrigued by the idea, but never fully sold. By the beginning of 1865, the Controller of the Navy, Rear Admiral Robert Spencer Robinson, warned Somerset and Sir Frederick Grey, the First Sea Lord, that “The Northern States would suffer little material injury by hostilities with Great Britain”, and that “very little damage it is apprehended could be done by Great Britain to the coastal towns of America by hostile operations. They are well defended now by land fortifications and the war with the South has called into existence a large fleet of vessels adapted for purposes of defence.” 25 On the other hand, American ironclads could hardly threaten the British Isles directly, though the menace to British interests on the North American and West Indian Station was serious. This effectively pulled the rug out from under much of Britain’s offensive-deterrence stance; protecting the land frontier of Canada by threatening the eastern seaboard of the United States. 26 Ironically enough, however, the outbreak of civil war in America so completely consumed much of the attention of the White House, that Seward’s wild suggestion of invading Canada as a desperate means of uniting North and South was quickly dismissed by Lincoln, while the merest hint of aggression—offered more by the British press than British foreign policy—was likewise enough to keep the Warrior safely anchored in Portsmouth, not off the approaches to New York City.

So completely obsessed was the mid-Victorian generation with ‘inventions’—with technology and ‘wonder weapons’—that ironclad revolutions like the Warrior or the Monitor were much more about their potency as floating symbols of propaganda and prestige. The real truths were much harder to capture and convey in contemporary newsprint, trans-Atlantic rumours and a myriad of semi-professional ‘opinions’. The real source of Warrior’s power was, after all, in everything that went into her construction, and everything that kept her fully operational, year-round, the world-over if need be. Thus, within a week of Robinson’s dour prognostication above, a first-hand, detailed report by U.S. Navy Chief Engineer J. W. King on the “dock yards and iron works of Great Britain and France” was so crushing that Welles ordered no less than a 1,000 copies of it to be printed for circulation to members of Congress. 27 “We have neither such dock-yards as are to be found in England and France, nor such a collection of iron ship building yards as there is in Great Britain; the combined capabilities of all the iron yards within our limits not being equal to the first of the great iron ship building yards on the river Thames.” 28 If America truly wanted to forge ahead as a leading maritime and naval power, it would take advantage of the brief yet crucial respite which the monitors had gained for the Union while it was at war with itself and commence a first-class government shipyard (in the manner of Chatham by 1865) at League Island, Philadelphia for the manufacture and maintenance of a Blue-Water Iron Navy. This didn’t happen until 1871, and American pre-eminence wasn’t firmly established until the Second World War finally called forth history’s greatest mobilisation of human and natural resources; a process above and beyond the creation of any fearful—yet ephemeral—war-winning ‘silver bullets’.

(Return to the October 2013 Issue Table of Contents)

—————————————————-

- “The central event in the American historical consciousness”, according to Pulitzer Prize-winning historian James M. McPherson, Ordeal By Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction, 4th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009), xxiii. ↩

- Donald L. Canney, The Old Steam Navy, Volume Two: The Ironclads, 1842-1885 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1993), 1. ↩

- From Ian F. W. Beckett, The War Correspondents: The American Civil War (London: Grange Books, 1997), 1. Christopher Hibbert notes that by 1863, “well over 300,000 copies were being sold” of the Illustrated London News alone—more than four times the circulation of The Times; The Illustrated London News Social History of Victorian Britain (London: Book Club Associates, 1976), 13. ↩

- See George A. Ballard (edited by G. A. Osborn and N. A. M. Rodger), The Black Battlefleet: A Study of the Capital Ship in Transition (London: Nautical Publishing Co., Lymington & the Society for Nautical Research, Greenwich, 1980), 42. ↩

- 12 January, 1861, Scientific American, “New War Steamers”; 7 June, 1856, B. S. Porter to Dahlgren, John A. Dahlgren Papers, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Washington, D.C.; 25-2-1861, Scientific American, “Altering Our Naval Vessels”; 9 February, 1861, Harper’s Weekly. ↩

- 21 May, 1861, Seward to Charles Francis Adams, from George E. Baker (ed.), The Works of William Seward, 5 vols. (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1884), 5: 244-5. ↩

- See for example, 2 December, 1861, A. Dudley Mann to Robert M. T. Hunter (Confederate Secretary of State), Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series II, Vol. 3, 307. ↩

- See 26 September, 1854, Ericsson to Napoleon III, John Ericsson Papers, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Washington, D.C. ↩

- 29 August, 1861, Ericsson to Lincoln, John Ericsson Papers, American-Swedish Historical Foundation, Philadelphia. ↩

- See James Tertius DeKay, Monitor: The Story of the Legendary Civil War Ironclad and the Man Whose Invention Changed the Course of History (Pimlico: Random House, 1999), 73-6. ↩

- 23 June, 1861, Palmerston to Somerset, Somerset Papers (Edward Adolphus Seymour, 12th Duke of Somerset), Buckinghamshire Record Office, Aylesbury (UK). ↩

- 20 January, 1862, Ericsson to Fox, quoted from John Ericsson, Contributions to the Centennial Exhibition (New York: Nation Press, 1876), 465-6. ↩

- James Phinney Baxter 3rd, The Introduction of the Ironclad Warship (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1933), 283. ↩

- 27 March, 1861; 28 December, 1861; 6 December, 1861, Palmerston to Somerset, Somerset Papers. ↩

- 31 March, 1862, Russell to Palmerston, Palmerston Papers (Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount), MS 62 (“Broadlands”), University of Southampton, Southampton (UK). ↩

- See for example, Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates, 3rd Series, Vol. 166, 3 April 1862, 430-44. ↩

- 5 December, 1861, Sir George Cornewall Lewis to Edward Twisleton, from Gilbert Frankland Lewis (ed.), Letters of the Right Hon. Sir George Cornewall Lewis, Bart. to Various Friends (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1870), 406; 24 October, 1862, Russell to Palmerston, Palmerston Papers. ↩

- 8 November, 1862, and 11 October, 1862, Scientific American; 10 May, 1862, and 31 May, 1862, Harper’s Weekly. ↩

- Arguably, the most successful Union ironclads of the Civil War were the lightly-armoured casemate-gunboats of the Cairo-class, or ‘Pook’s Turtles’. These light-draft, partially-protected vessels spearheaded combined operations in the Western theatre of the war and helped ‘cut the Confederacy in two’. They were, however, as Rear-Admiral David Porter wrote to Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, “built for temporary purposes only, or until monitors could take their places.” Against “earthworks on elevated positions”, “No vessels have been more successful than the Mississippi gunboats…Still they were deficient in one aspect, as they were very vulnerable, suffered a good deal, and proved that in the end the monitor principle, from its invulnerability, was the only thing that could be safely depended on,” 16 February, 1864, see the Congressional Globe, 38th Congress, 2nd Session, “Report of the Secretary of the Navy”, Appendix, 549-52. ↩

- 15 January, 1865, Porter to Welles, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Vol. 11, 600-2. ↩

- 7 April, 1864, Rodgers to Welles; and 28 January, 1864, Dahlgren to Welles, in Report of the Secretary of the Navy in Relation to Armored Vessels (Washington, GPO, 1864), 592-4; 579-88. ↩

- 26 September, 1864, London Times; 24 September, 1864, Punch, or the London Charivari, “Mrs. North and Her Attorney”; 18 March, 1865, Army & Navy Journal. ↩

- 3 November, 1864, New York Herald. ↩

- 4 April, 1862, Charles Francis Adams to Charles Francis Adams, Jr., from Worthington Chauncey Ford (ed.), A Cycle of Adams Letters, 1861-1865, 2 vols. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920), 1:123. ↩

- 9 January, 1865, Robinson to Board of Admiralty, British National Archives (Kew), ADM 1/5931. The alternative of building “a new navy for the lakes of Canada”, Somerset commented in an enclosed note dated 1 January, 1865, “could hardly be undertaken without the direct sanction of Parliament,” and would “only mislead the Canadian government as to the extent of aid which this country would give them.” ↩

- See for example, Kenneth Bourne’s work on Britain and the Balance of Power in North America, 1815-1908 (London: Longmans, Green and Co. Ltd., 1967). ↩

- 16 January, 1865, Welles to A. H. Rice (Chairman of the Committee on Naval Affairs), U.S. National Archives, Record Group 45, Entry 5. ↩

- See the Congressional Globe, 38th Congress, 2nd Session, “Report of the Secretary of the Navy”, enclosure No. 18, 1216-59. ↩

Pingback: Warrior -all above board « eljaygee