By Diana L. Ahmad

Missouri University of Science and Technology

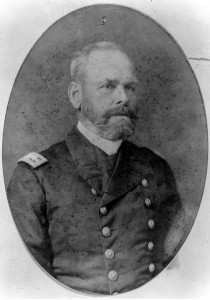

Captain Benjamin Franklin Tilley. Image PH-30 , courtesy Polynesian Photo Archives, The Dwyer Collection, Feleti Barstow Public Library, American Samoa

By 1900, with the acquisition of Guam in Micronesia and eastern Samoa in Polynesia, the United States had successfully expanded its borders into the Pacific Ocean. The Department of the Navy ruled these islands for fifty years and assigned Commander Benjamin F. Tilley to eastern Samoa and Captain Richard P. Leary to Guam as the first American officials. 1 Tilley worked with the islanders to secure their traditional culture and lands, while simultaneously developing a kinship with the Samoans that is still celebrated. Leary, on the other hand, sent his second in command to work with the people, while he remained aloof, longed to return to the mainland, and is rarely remembered. The straightforward, law-abiding governor of Guam left the island in less than a year with nary a person bidding him farewell, while the controversial governor of American Samoa left Samoans longing for his return.

The acquisition of the islands resulted from diplomacy and war. A prize of the Spanish-American War, along with Puerto Rico and the Philippines, the Treaty of Paris awarded Guam to the United States and American sovereignty began in April 1899. 2 For eastern Samoa, soon called American Samoa, the United States annexed the islands as a result of the Convention of 1899, a diplomatic agreement whereby the Germans, British, and Americans split Samoa into two sections giving western Samoa to Germany, eastern Samoa to the United States, and awarding special considerations elsewhere in the Pacific to the British. 3

Commander Tilley and Captain Leary graduated from the United States Naval Academy, where Captain Leary ranked in the bottom twenty percent of his 1864 graduating class of fifty, and Commander Tilley graduated at the top of his 1867 class of eighty-seven. While Tilley was too young to participate in the Civil War, Leary served in a blockading squadron off Charleston, South Carolina, during the conflict. Both men served as line officers on vessels in the Pacific during the 1870s and 1880s. Neither man possessed much experience with civil government. 4 The men would soon face similar challenges in running civil governments and controlling the naval stations on their respective islands.

Captain Richard P Leary USN. Special Collections & Archives Department, Nimitz Library, U.S. Naval Academy.

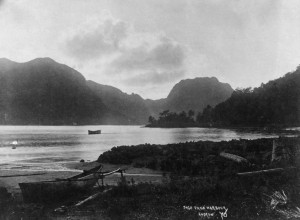

Conveniently located for coal burning vessels, Guam and American Samoa possessed excellent harbors vital to the Navy and commercial shipping. The American takeover of Tutuila gave the United States what many considered the most valuable harbor in the South Pacific, Pago Pago, and provided the Navy with the only inhabited American possession south of the equator. Tilley described Pago Pago as “one of the most beautiful and valuable harbors in the whole world,” with an importance that grew with the possibility of a Central American isthmian canal. Tilley also noted that Tutuila’s harbor was much safer than that at Apia, Upolu, in German Western Samoa, where an 1889 typhoon killed over one hundred people and destroyed or severely damaged six naval vessels. 5 Guam, located on the seven thousand mile route between San Francisco and the now American city of Manila in the Philippines, possessed Apra Harbor, a significant anchorage for naval and merchant vessels alike. In 1899, Ensign C. L. Poor noted that Guam’s “naval and military value will increase every year, and it will be of the greatest possible service to us in our future relations in the Pacific.” 6

The takeover of the islands came quickly and with little thought for the future of the territories. President William McKinley issued executive orders that established a legal basis for the governments of Guam and American Samoa and allowed the United States Navy to appoint officers to take control of the islands. In neither case were the islanders consulted about their futures; instead, Commander Tilley and Captain Leary determined those. On January 12, 1899, Secretary of the Navy John D. Long appointed Captain Leary as the first American Governor of Guam and Commandant of United States Naval Station—Guam. Arriving on August 7, 1899, Leary ended nearly four hundred years of Spanish rule and a fourteen month period of confusion between the initial American takeover of the island during the war and his arrival. Secretary Long ordered Leary to maintain Spanish laws for the time being and develop a benevolent relationship with the islanders. 7

As for Samoa, Commander Tilley learned of his new responsibilities on April 4, 1900, while at Apia. Already assigned to Tutuila to oversee the construction of a wharf and coaling station at Pago Pago Harbor, Tilley was a convenient first choice as the new ruler of the islands. He immediately arranged for the cession of Tutuila and several subsidiary islands, an act permitted by the Convention of 1899 and the American belief in manifest destiny. Secretary Long ordered Tilley to take care of the eastern Samoan islands in the name of the United States, to establish a naval station at Tutuila, and to develop a cordial relationship with the Samoan people. The Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Charles H. Allen, invested Tilley “with authority over the islands in the group embraced within the limits of the Station,” and instructed him to “exercise care to conciliate and cultivate friendly relations with the natives.” Allen also ordered Tilley to establish “a simple, straightforward method of administration, such as to win and hold the confidence of the people….” 8 One of the most significant differences between the situations of Leary and Tilley was the Spanish rule over Guam. Samoa had never been ruled by Europeans, although since the 1840s the islands had dealt with European and American involvement in a dispute over who should be the next king of the archipelago. In that regard, Tilley was luckier as he did not have to deal with a well-entrenched European government structure; however, he worked within a strict Samoan one that had operated for centuries. Tilley established a civil government from its roots, while Leary changed the existing European government-style to fit the American way of doing things.

Relations between Europeans and Americans with the Samoans began in the early eighteenth century with the voyage of Jacob Roggeveen from the Netherlands and followed shortly after with the French explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville. Although neither explorer set foot on the Samoan Islands, both expeditions met Samoans who paddled their canoes to the Western ships anchored off shore. By the early nineteenth-century, Westerners began to choose to stay on the islands, although they were often men of bad reputations and included deserters, blackbirders, and escaped convicts. Soon some of these men participated in the wars between various Samoan groups that were vying for leadership of the islands. At about the same time, American missionaries hoping to save souls and whalers wishing to replenish supplies for the ships arrived in the Samoan group. 9

During the nineteenth century, with more and more Westerners coming to the Samoan Islands, each with their own agendas, conflicts between Samoans grew about whom best would serve the islands. In 1879, in order to protect Western interests in the islands, the British, Germans, and Americans established the Municipality of Apia. The conflicts between the Samoans increased in 1881 with the death of the current king and the debate about his replacement. The Germans supported Tamasese, while the British and the Americans supported Malietoa Laupepe. Eventually, even Robert Louis Stevenson, who retired to Upolu in western Samoa in 1890, became involved in the conflict between Samoan groups about the new leadership. 10 Commander Tilley arrived at Tutuila shortly after the often violent conflict had ended.

Unlike Samoa, Guam had been claimed by Spain since the middle of the sixteenth century, even though Ferdinand Magellan was the first European explorer to land on the island in 1521. By the eighteenth century, opposition to Spanish rule ended and Catholicism had become well-established. Guam’s location in the Western Pacific placed it largely out of the way of commercial vessels who generally plied the waters of the South Pacific from California or from Europe via the Straits of Magellan. Spanish galleons often sailed due west from Acapulco, Mexico, to Guam, and on to the Philippines. 11 Captain Leary took command from an island governed by the Spanish for over three hundred years.

Captain Leary learned of his new assignment while stationed stateside. On January 24, 1899, Leary reported aboard U.S.S. Yosemite to prepare for his journey to the Western Pacific. He spent four months outfitting Guam’s new station vessel and purchasing $10,000 worth of goods, including materials to repair the former Spanish governor’s home, a water treatment plant, roofing for coal sheds, an ice plant, scientific equipment, and agricultural supplies for the islanders. On May 10, 1899, President McKinley bade farewell to Yosemite as she sailed from New York en route to the Mediterranean, thence through the Suez Canal, into the Indian Ocean, on to Singapore and Manila, and finally dropped anchor at Guam on August 7, 1899. Three days after his arrival, Leary, a Protestant, issued his first proclamation abolishing the political authority of the Catholic clergy on Guam, and guaranteeing freedom of religion for all. He also explained that public lands and property now belonged to the United States and that Spanish laws would remain in force until modified or annulled. 12

On April 17, 1900, Tilley’s official announcement that eastern Samoa had become part of the United States led to a two-day party, perhaps facilitated by the fact that the Samoans had already known Tilley for several months and that they welcomed becoming a part of the United States. Tilley sent invitations to the German representatives in Apia, including Dr. Wilhelm Solf, who had taken control of Western Samoa on the first of March, for the flag raising ceremony on Tutuila. Tilley also sailed to Manu‘a at the eastern end of the archipelago to convince the Tui Manu‘a, king of the Manu‘a group, to accept the new American government. The Commander explained that the United States did not intend to oppress the islanders, but instead meant “to shield them from unscrupulous people.” The Tui Manu‘a agreed to accept the “sovereignty and protection of the United States,” but would not cede his island group. 13 It took the Manu‘ans until 1904 to cede their islands to the United States, but the king agreed to attend the festivities on Tutuila.

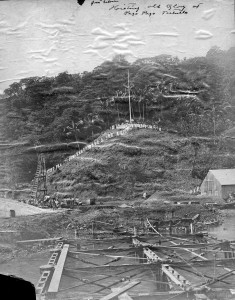

At the flag-raising event, the Commander read a proclamation from President McKinley declaring the islands “to be under the sovereignty and protection of the United States of America…,” after which Mrs. Henry Hudson, wife of U.S S. Abarenda’s Chief Boatswain Mate and first Navy wife to live in American Samoa, hoisted the flag. The Samoans followed with a number of speeches accepting American sovereignty saying, for example, “We depend on the government and we hope that we indeed and the government will be prosperous; that the government will correctly guide and advise us in order that we may be able to care for and guard well and uprightly our different villages and also our districts.” Several days earlier, Tutuila chiefs wrote to Commander Tilley expressing pleasure with the American acquisition of their islands saying, “We rejoice with our whole hearts on account of the tidings we have received… [that] only the government of the United States of America shall rule in Tutuila and Manua.” 14 With the American acquisition of eastern Samoa, the nearly three generation Samoan inter-island conflict over leadership of the island group came to an end.

Flag Raising on Tutuila, 17 April 1900. Image PH-102-B, courtesy Polynesian Photo Archives, The Dwyer Collection, Feleti Barstow Public Library, American Samoa

The ceremony continued with a religious service performed by the local Christian missionaries, a twenty-one gun salute from Abarenda and the visiting German vessel, Cormoran, songs from school children, a Samoan feast in Pago Pago village, and traditional Samoan dances, sports, and games. Tilley commented that at the festival that followed the flag raising, the Samoans “ate so much pig that it is a wonder that they survived.” The United States Consul General at Apia, L. W. Osborn, reported to the Assistant Secretary of State David J. Hill that “all seemed much pleased to feel that they were henceforth to be under the flag of ‘Amileka.’ I am of the opinion that the new arrangement starts off under the most favorable auspices in Tutuila and Manua, the U.S. psossessions [sic].” Ten days later, Osborn wrote, “The Tutuila people are much pleased, and very enthusiastic, and the Governor [Tilley] has their respect and confidence.” 15

It would be up to the Navy’s appointees to learn as quickly as possible how to work with the islanders. Tilley believed the Samoans were “almost, without exception, enthusiastic over their annexation by the United States” and he hoped that under American guidance the Samoans would “rise to a high degree of civilization.” 16 Vital to his mission, the Commander needed to learn fa‘a Samoa or the Samoan Way. Fa‘a Samoa developed over many centuries into a complicated family and government structure that consisted of aiga or family/kin groups, titled chiefs or matai who earned their rank based on birth and ability, and the fono or village assembly. The family’s assets were controlled by the title, not the person holding the title. The system also called for fa‘aaloalo or respect earned through service to the family or village. Several levels of matai titles existed, including ali‘i (lower ranking chiefs) and tulafale (orators). The basic source of authority came from the ali‘i and the tulafale distributed the food and wealth at official functions. 17

Tilley recognized the significance and active role fa‘a Samoa played in the region and quickly adjusted to it. To foster the good will of the Samoans, the Commander pursued a policy of conciliation with the island leaders. According to Tilley’s Secretary of Native Affairs, Edwin W. Gurr, the Commander did not want to force the Samoans into anything and “Tilley went among the people, ingratiating himself with them; accustoming himself to their habits, and studying the characters of the most prominent people.” Dr. Edward M. Blackwell, Abarenda’s medical officer, concurred with Gurr that the Commander wanted “to get in touch with the natives.” 18 Not only did Tilley visit the local villages, he also transported villagers aboard the station vessel to Western Samoa to visit relatives or to do business there. The efforts to learn about the people and the simple act of assisting Samoans in their travel plans demonstrated that Tilley was not the usual imperialist leader sent to alter indigenous cultures, but instead indicated a man interested in bringing American civilization, for better or worse, to a place while simultaneously maintaining as much of the vitality of the local culture as possible.

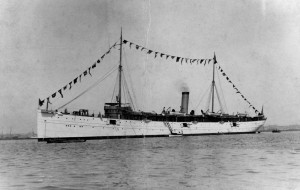

USS. Abarenda on Flag Raising Day, 17 April 1900. Image PH-OL-102-K, courtesy Polynesian Photo Archives, The Dwyer Collection, Feleti Barstow Public Library, American Samoa

Significantly different from Tilley’s approach in American Samoa, yet possessing equivalent executive, legislative, and judicial authority, Leary chose to pass on much of his power to his Lieutenant Governor, United States Navy Lieutenant William E. Safford who arrived at Guam aboard U.S.S. Brutus on August 13, 1899. Not finding the conditions of his new island assignment to his liking, Leary remained aboard Yosemite for three months while awaiting the completion of repairs on the former Spanish governor’s palace so he could move onshore. Leary further separated himself from the local population by leaving orders that he did not wish to be disturbed unless in an emergency. This alienation from the locals was made even more pronounced during the early months since Yosemite was anchored approximately five miles by rough roads and two miles by water away from Agana. 19

No finer assistant for Leary could have been found. Lieutenant Safford sounded much more like Commander Tilley in his views of the island and its inhabitants. About Guam he wrote, “Surely I had found Arcadia” and “Nothing more beautiful than this island could be imagined; and no one could wish for more pleasant occupation nor for kinder friends.” Safford became the trial judge of local cases, the registrar of property, and the auditor of the treasury on Guam. Personally, he purchased several properties so he could have a house, a garden, and a nursery for the plants he introduced to the island. In addition to hiring Chamorros to work on his properties, Safford entertained many Guamanian friends in his home. 20

As with Leary and Tilley, Safford graduated from Annapolis in 1880, although he never served as a line officer. He spoke Spanish and German and soon learned Chamorro, the native language of Guam and the Mariana Islands. In 1902, two years after leaving Guam, Safford left the Navy, and became a well-known botanist, ethnologist, and philologist, and in 1905, the Lieutenant published The Chamorro Language of the Island of Guam and Useful Plants of the Island of Guam, the first such books in English. 21

As for Tilley’s assistants, he looked to several people, including Chief Boatswain and Mrs. Henry Hudson, Lieutenant Commander Edward J. Dorn, and Mr. Edwin W. Gurr. Chief Boatswain Hudson took over responsibilities for the finances of American Samoa, customs operations, discharging cargo, and the construction of Naval Station Tutuila. Mrs. Hudson served as the first postmaster of the territory and photographed much of the island during her stay there. The couple lived in a cottage on Naval Station. Lieutenant Commander Dorn described her as “quite a superior woman, educated and refined.” 22 On July 25, 1900, Dorn reported for duty as Tilley’s Executive Officer and Navigator. Tilley also appointed Dorn the Assistant Commandant of the United States Naval Station—Tutuila. In November 1900, Tilley left for New Zealand for ship repairs and to get supplies leaving Dorn in charge of the territory. Tilley instructed him to “pursue a conciliatory policy” with the Samoans as the islanders “appear to be very friendly and were satisfied with the new government.” Upon his return, the Commander informed the Assistant Secretary of the Navy that Dorn administered the Territory’s affairs “with much tact and efficiency. He has pursued the conciliatory policy which has been adopted with the natives, and while treating them with firmness, has won their good will.” 23

In August 1900, Tilley appointed Gurr the Secretary of Native Affairs and he became one of Tilley’s most valued and trusted assistants. Originally from New Zealand, Gurr had served as a barrister for the Supreme Court of Samoa at Apia during the 1890s when a tripartite commission of Americans, Germans, and British ruled the Municipality of Apia. Married to a high chief’s daughter, Gurr understood the Samoan language, as well as fa‘a Samoa. His father-in-law, Seumanu Tafa, helped save lives in Apia harbor during the 1889 typhoon. Gurr proved familiar with land claims and helped clear up ownership problems on the islands. 24

Holding the ultimate authority in their respective territories, the development and responsibility for the laws governing American Samoa and Guam belonged only to Tilley and Leary. In Secretary Long’s orders to Leary, he stated that the governor of Guam needed to maintain “the strong arm of authority” on the island. Tilley received similar instructions and viewed himself as the “supreme lawgiver.” 25 Safford carried out the laws passed by Leary, while Tilley created the Fita Fita, young Samoan men enlisted as Landsmen in the United States Navy that helped him maintain order and enforce his decisions and laws. 26

After abolishing the political rights of the clergy on Guam and disgruntled by the Spanish priests’ support for concubinage and the fathering of illegitimate children, Leary, a Protestant and bachelor, deported the priests, save Father José Palomo, the first Catholic priest of Chamorro ancestry. Leary also banned Catholic festivities celebrating a village’s patron saint and the tolling of church bells in the mornings and evenings. 27 Unlike heavily Catholic Guam, American Samoa had missionaries from Protestant, Catholic, and Mormon groups long before the American takeover of the islands, and Tilley’s only concern regarding religious practices involved making sure that one religious service did not disturb another. 28

In a series of general orders, Leary changed the way of life on Guam. He found the custom of Guamanians living and raising families together without legal or religious ties to be repugnant to his conception of decency and modern life. This practice developed because of the Catholic ban on divorces that resulted in islanders sometimes leaving their legal spouses to establish families with others. To rectify this problem as Leary saw it, on September 15, 1899, he issued General Order No. 5 requiring all unwed couples on the island to marry before the end of the year. To facilitate these marriages, the government allowed divorces and temporarily waived the marriage license fee. On January 1, 1900, Leary also banned the system of peonage whereby lenders forced borrowers to work off their debts by laboring for their creditors for many years. 29

Unlike Leary, Tilley had no intention of drastically altering the customs and laws of the Samoans; yet, in a more sweeping manner, the Commander changed the way imperialists worked with those they governed. On April 30 and May 1, 1900, Tilley established his two most significant laws for American Samoa. On April 30, Tilley issued Regulation No. 4 prohibiting the Alienation of Native Land in Tutuila and Manu‘a and forbidding the sale of Samoan land to foreigners. The lands could be leased for up to forty years for any purpose, but only with the approval of the Commandant of Naval Station. Violation of the regulation could result in a $200 fine or forfeiture of some or all of the land to the government. In Regulation No. 5, A Declaration Concerning the Form of Government for the United States Naval Station Tutuila (May 1, 1900), Tilley promised that the naval government would uphold Samoan customs unless the Samoans wanted them changed or if the traditional customs came in direct conflict with American laws. It also established the three districts of American Samoa, and vested judicial power in the High Court, District Courts, and Village Courts with the Commandant serving as President of the High Court. Further, Regulation No. 5 established the Chief Secretary of Native Affairs to serve as the secretary to the Commandant and to supervise the district leaders. 30 With the passage of Regulations No. 4 and 5, Tilley showed commitment to the Samoan communal land preservation system, as well as to the maintenance of fa‘a Samoa.

On Guam, Captain Leary did not go as far as Commander Tilley in preserving the land claims of the islanders; however, he issued General Order 15 that protected the land claims of the islanders if they registered their lands with the government. As in many other instances, the task of identifying the land claims fell to Lieutenant Safford. Safford called together the large land owners and asked them to identify their holdings on a chalk map on the floor of his office. After some changes, land titles were granted. Safford later wrote that he hoped that “for this, at least, we hope that the people of Guam may remember us with gratitude.” 31

Despite Tilley’s intentions to avoid interfering with Samoan customs, one significant incident embodied a direct conflict with fa‘a Samoa. In what became known as the Skipjack Case, a Samoan man, Fagiema, caught a fish known as a skipjack (member of the bonito family) and took it home to his family. According to fa‘a Samoa, this type of fish should have been given to the high chief of the region. The high chief discovered the infraction of the rules and punished the offender by evicting Fagiema and his family, burning down his house, killing his pigs and chickens, destroying his crops, and telling him that he may no longer hunt, fish, or gather fruit in the area again. Eventually, Commander Tilley heard about the incident and ordered the arrest of the chief who called for Fagiema’s punishment. The Chief was tried by the High Court and told to make restitution to Fagiema, stripped of his chiefly title, and confined to the Pago Pago harbor area for one year. Tilley decided that, in this case, fa‘a Samoa was unfair and the customary rules would be overturned. Although a small incident in itself, its significance was far greater. Tilley’s decision directly attacked fa‘a Samoa and demonstrated a clash between the American and Samoan laws and customs. 32 The incident ended with Tilley’s decision, indicating that the Samoans either simply accepted his decision or did not loudly express displeasure with it.

Tilley and Leary approached their duties and responsibilities very differently. While Leary limited what Catholic priests could do on Guam, Tilley worked with the missionaries who lived on Tutuila. Tilley likely believed that the best way to accomplish what he wanted to do was to work with the missionaries who lived in American Samoa. Tilley’s behavior with the islanders demonstrated that he enjoyed their company and respected their laws and customs, while Leary’s lack of participation in Chamorro culture led to a lack of understanding of the islanders’ lifestyle. Lieutenant Safford reveled in all things Chamorro and as a result, the islanders enjoyed his company and became his friends. It is probable that something as simple as the personality of the two men resulted in how they impacted their respective assignments.

Both Navy leaders sought to improve the quality of life on their respective islands. Navy doctors assigned to Guam and American Samoa willingly provided medical assistance free of charge. On Guam, Navy medical personnel brought care to the communities of Agana, Piti, Sumay, and Agat. In writing about Yosemite’s junior medical officer, Safford opined that through Dr. Alfred G. Grunwell’s “untiring devotion to his duty, his gentleness and kindness, he has done more than anyone else to win for us the love of the natives.” 33 On Tutuila, whenever Commander Tilley visited villages on inspection trips, he brought Dr. Blackwell with him. Although it is unclear what her relationship was to the United States Navy or to the Samoans, Mrs. Pike, a part-Tahitian woman living on Tutuila, helped the doctor with the patients, as well as with translation duties. Blackwell built a boat to take him to villages needing his assistance when he travelled without the Commander. Both leaders sent requests to the Department of the Navy for funds to build dispensaries, but as with other financial requests, they went unfulfilled. With some of Tilley’s funds from his small island budget, he purchased a trader’s store to serve as a small medical facility. 34

Despite the lack of additional government monies, health conditions in both island groups improved with the coming of the Navy. On Guam, the Navy built a better drainage system, installed a water distillation plant and water tanks, required village outhouses, and enforced garbage collection. On Tutuila, Tilley’s efforts to clean up the polluted water sources and build village outhouses reduced the incidence of filariasis, also known as elephantiasis, among the Samoans. 35

In the area of education, the commandants desired more schools for the people. Leary established a public school system and banned religious education, while Tilley supported the schools run by the Catholic, Protestant, and Mormon missionaries operating on the island when he arrived. Once again, Tilley proved flexible in his command of the island, while Leary did not. Schools funded by the missionaries would not burden American Samoa’s meager finances. Tilley wanted even more schools built and desired that the Samoans learn English with the boys trained in manual skills and the girls educated in the domestic sciences. On January 23, 1900, Leary legislated that Guamanians learn how to write their names and recommended that they learn English. Several private schools opened on Guam to teach English, including one run by Lieutenant Albert Moritz, Yosemite’s chief engineer. During the evenings, Safford taught English to Chamorro friends in his home. 36

Paying for the improvements to Guam and American Samoa proved to be a problem for Leary and Tilley alike. Leary received $10,000 to start; however, he spent much of that outfitting Yosemite and purchasing supplies before he arrived. Once on Guam, Leary continued the taxes established by the Spanish and collected funds from, for example, the sale of postage stamps, import duties, license fees, and fines. As far as exports were concerned, Guam possessed a small amount of copra, the dried coconut meat used to make soap in the West. According to Safford, “nothing pays on this island so surely as coconuts,” yet he remembered that coconuts could be destroyed by typhoons. 37

Unlike Leary, Tilley took an activist approach to obtaining the funds he needed. As on Guam, Tutuila had copra and Tilley took advantage of the local crop. The Commander observed that copra traders paid Samoans one and a quarter cents per pound for copra, but sold the item on the open market for the best price available and kept the profits for themselves. Needing a way to finance his government and believing that the traders mistreated the Samoans in their dealings over the coconut meat, Tilley took over the copra export business. The Navy commander more than doubled the price given to the Samoans, allotting them three cents per pound, but charging them one dollar per Samoan as a “handling tax” for selling the copra. Between 1901 and 1902, approximately $10,000 came from the copra fees. 38

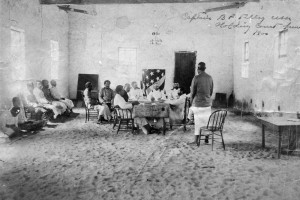

Captain Benjamin Franklin Tilley Holding court, 1900. Image PH102-C, courtesy Polynesian Photo Archives, The Dwyer Collection, Feleti Barstow Public Library, American Samoa.

Despite the many successes for Leary and Tilley, all did not go smoothly for the two men. Governor Leary’s problems began when the Navy released his reports to the press explaining that he sent the Spanish priests away from the island. The Catholic clergy in the United States quickly reacted and the Archbishop of New Orleans, who was also the apostolic delegate to the American territories, asked to visit Guam on his way to the Philippines. At first, Leary agreed, but then reneged when the Archbishop requested that Leary cancel his previous orders about the clergy and the religious practices of the islanders. As a result, General Elwell S. Otis in the Philippines ordered Major General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Wheeler to go to Guam to investigate Leary’s actions. Offended by the Army wishing to investigate a Navy command, Rear Admiral J. Crittenden Watson, Commander in Chief of the United States Naval Force on the Asiatic Station, told Leary to receive Wheeler but not to take any orders from him. 39

Arriving on February 6, 1900, and accompanied by his secretary and William Bengough from Harper’s Weekly, Wheeler toured the island with Safford. During his short visit, he interviewed Safford, Leary, Father Palomo, and native officials. Safford noted that Wheeler’s questions “bore evidence to his interest in the success of the United States colonial policy.” Later, Safford also wrote that “General Wheeler seemed deeply touched by the fervent expressions of loyalty and friendship on the part of these good people, so different, he said, from what he had found in the Philippines.” In his report to Washington, Wheeler commented that the religious restrictions were a hardship for the islanders and that Apra Harbor needed a breakwater. His report led to no changes in the administration of Captain Leary and the matter came to an end. 40

In contrast, Commander Tilley’s difficulties led to a court-martial trial. Displeasure with Tilley’s rule came from men under his command and from Anglo settlers and visitors to the islands, but not from Samoans. The accusations against Tilley included his being so intoxicated that he could not walk back to his ship from a tavern in Western Samoa and as a result, the liberty for his ship’s crew was “stopped for fear we would see him in such a state.” 41 Tilley’s Executive Officer, Lieutenant Commander Dorn, found Tilley’s drinking enough of a problem to have a one-on-one discussion with Tilley about his alcohol consumption. Dorn reminded Tilley that the Commander had passed out on the poop deck of Abarenda with a Samoan woman, failed to go on the bridge when the vessel left Apia harbor, and became “too familiar with women” at a luncheon sponsored by Governor Solf. Tilley promised to reform and acknowledged that such a report would ruin his career. Dorn agreed not to report Tilley to the Secretary of the Navy; however, despite giving Tilley his word, the Executive Officer wrote Secretary Long the same day as his talk with the Commander. 42

Although not witnessing Tilley’s alleged behavior firsthand, Charles Keeler, from the California Academy of Sciences, heard about Tilley’s conduct while visiting Samoa in 1901 and claimed that “no one dared to tell the story” of Tilley’s escapades. Keeler sought out the assistance of H. J. Moors, a trader and hotel owner at Apia, who had had dealings with Tilley on several occasions. The letters between Keeler and Moors about Tilley’s behavior were sent to Dorn so he could deliver them to the Department of the Navy. Moors added to the letters saying that he did not want “to injure Capt. Tilley, but I do not wish to see him here again disgracing our flag, or making our government ridiculous at Tutuilla [sic] by his behavior there.” 43 Eventually, the campaign against Tilley involved Dr. Blackwell of Abarenda, rivalries between island hotel owners, and the step-daughter-in-law of Robert Louis Stevenson. Most of the complaints involved Tilley’s “drunken revels in Apia,” horse rides through the streets while intoxicated “with a notorious native woman,” and “carouses in Pango Pango [sic].” In the midst of the complaints about Tilley, the Samoans sent letters supporting the Commander stating that they were “satisfied because the good Governor you sent to us has been faithful and kind to us, and has kept his promises.” 44 Ironically, in September 1901, in the middle of the anti-Tilley campaign, the Navy promoted him from Commander to Captain as his career, according to the New York Times in October 1901, had been thus far “unblemished.” The newspaper had apparently not been apprised of the allegations against him. With all the attacks against Tilley, Secretary Long finally demanded evidence of Tilley’s misconduct or a cessation of the accusations. Shortly after that, the Navy called for the Captain’s court-martial. 45

Pacific Fleet Rear Admiral Silas Casey, Rear Admiral Robley D. Evans, and at least eight Navy captains gathered in Pago Pago for the court-martial proceedings. One of the most important figures in the accusations against Captain Tilley, Lieutenant Commander Dorn, left Samoa in October, just before the court-martial because of an alleged third heart attack. The Samoans organized a reception for the visitors and approached the Navy’s representatives with “scowls on their faces and demanded to know why their White Father was not among us.” Apparently, the Samoans were unaware that Tilley was under house arrest and unable to attend the festivities. After speaking with Rear Admiral Casey, the group left “satisfied that their beloved governor would receive kind and fair treatment.” 46

On November 9, Tilley pleaded not guilty to the counts against him, including “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman,” “scandalous conduct,” “drunkenness,” and “neglect of duty.” The government produced three witnesses, two testifying on behalf of Tilley and one against him. Dr. Blackwell, the sole witness for the prosecution, could not swear that Tilley’s behavior was caused by heat exhaustion or drunkenness. Expressing disdain for the proceedings in his memoirs, the doctor later wrote that “all the other witnesses who caroused with [Tilley] testified for him and, as the saying goes, ‘Dog won’t eat dog.’” After listening to dozens of defense witnesses, the court adjourned and soon delivered a verdict of not guilty of all charges and acquitted Captain Tilley “most fully and honorably” and restored him to duty. Rear Admiral Evans claimed he had never seen “a case so weak as this one was, nor one where there was so little ground for charges.” 47 Although the court acquitted him, Tilley left Tutuila for his next assignment soon after the conclusion of the trial.

Tilley may have displeased the Anglo settlers and visitors, and his fellow officers; however, he certainly worked well with the islanders. Approximately a year after the court-martial, the Samoans sent a letter to the Department of the Navy asserting Tilley “did all that was good. We know of no wrong that he has done. There is no dissatisfaction towards the government; there is no dissension amongst the people. The people of Tutuila want no other to be here with them but Captain Tilley. Bad customs, bad laws have been abolished by Captain Tilley. He is the father of Tutuila and Manua.” 48

After relatively brief periods of time in the islands, Captains Leary and Tilley traded their assignments for positions stateside. Following only six months as governor, and only three of those months actually living on Guam, Captain Leary contacted the Secretary of the Navy about being reassigned claiming he had been at sea for nearly four years and needed to go home. The Secretary of the Navy complied with his request and Leary, as well as Lieutenant Safford, left Guam on August 2, 1900, aboard U.S.S. Yosemite. The Navy reassigned Leary to League Island Navy Yard, and soon after that to U.S.S. Richmond. Leary passed away just after Christmas 1901. After leaving American Samoa in November 1901, Tilley served at Mare Island Navy Yard for three years and then commanded U.S.S. Iowa for two years. On February 24, 1907, the Navy promoted him to Rear Admiral. Less than a month later, however, Rear Admiral Tilley died of double-pneumonia. 49

Neither Leary nor Tilley received specific orders about how to run the new territories, instead the Secretary of the Navy told the Captains to do the best they could with virtually no funds and no guidance. The Captains enjoyed successes in their island governments, such as improving the sanitary conditions, the educational systems, and the roads. Both leaders also faced opposition to the way they ruled their respective islands, Leary from the Guamanians and Tilley from the Anglo population of American Samoa. Leary chose to work through his assistant, Lieutenant Safford, who won the admiration of the Guamanians he encountered, while few Guamanians even knew the governor. On the other hand, Tilley’s style was perhaps not the most desirable; yet, he earned the love and respect of the islanders. Even today, Tilley’s impact can be seen in the Revised Constitution of American Samoa that maintains fa‘a Samoa and Samoan land ownership. Captain Leary and Captain Tilley established governments in America’s new empire with only the materials they had on hand and only the experience they brought with them. As men-on-the-spot, Leary and Tilley succeeded in the only way they knew how. Leary appointed an assistant better equipped to handle the situation than he was, while Tilley learned to appreciate the Samoan culture, but became too familiar with the Samoans.

(Return to the October 2013 Issue Table of Contents)

- Commander B. F. Tilley was promoted to Captain while stationed on Tutuila. As such, Tilley’s rank in the text reflects how people either addressed him or his rank at that time. ↩

- Robert F. Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam (Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 1995), 1, 113. ↩

- Thomas F. Darden, Historical Sketch of the Naval Administration of the Government of American Samoa (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1951), x-xi; David M. Pletcher, The Diplomacy of Involvement: American Economic Expansion across the Pacific, 1784-1900 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2001), 80-82. ↩

- “Featured Governor of the Month,” Office of the Governor of American Samoa, http://www.asg-gov.com/governorsgallery_tilley.htm (April 2, 2002); “Capt. ‘Dick’ Leary Dead,” New York Times, December 28, 1901; United States Naval Academy Alumni Association, personal telephone call, June 1, 2009. ↩

- General Study of American Samoa, Box 1, Record Group 284, National Archives—San Bruno, California (hereinafter cited as RG 284, NARA-SB); William Churchill, “Our Most Contented Dependency,” Harper’s Weekly 56:13 (April 20, 1912), np; David Starr Jordan and Vernon Lyman Kellogg, “Tutuila (U. S.),” Atlantic Monthly 94:562 (August 1904): 208; Rodney Blake, “Our Colony in Samoa,” The Era Magazine 12 (September 1903): 220: Benjamin F. Tilley, “The United States in Samoa,” The Independent 52 (August 2, 1900): 1841-1842; “The Value of Pago Pago,” New York Times, April 13, 1900, 5:5. ↩

- Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall, 1, 112; Willard French, “An Isolated American Island: How We Are Neglecting Our Duty to Guam,” The Booklovers Magazine (March 1905): 370; Ens. C. L. Poor, “Guam—Our Miniature Colony in Mid-Pacific,” Harper’s Weekly 43:2238 (November 11, 1899): 1135. ↩

- Earl S. Pomeroy, “Colonial Administration by United States Naval Officers,” Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute 69 (October 1943): 1321; Paul Carano and Pedro C. Sanchez, A Complete History of Guam (Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1964), 184; Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall, 114. ↩

- General Study of American Samoa, Box 1, RG 284, NARA-SB; Charles H. Allen to Benjamin F. Tilley, February 17, 1900, File: General Interest, 1900-1919, Box 1, RG 284, NARA-SB. ↩

- Joseph Kennedy, The Tropical Frontier: America’s South Sea Colony (Mangilao, GU: Micronesian Area Research Center, 2009. ↩

- Robert Louis Stevenson, A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa (Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 1996); Kennedy, The Tropical Frontier, 27-33. ↩

- Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall, 5, 18, 37. ↩

- Lt. Louis M. Nulton, “The Expedition to the Island of Guam,” The Independent 51 (May 1899): 1357; Evelyn Gibson Nelson and Frederick Jens Nelson, The Island of Guam: Description and History From A 1934 Perspective (reprint: Washington, D.C.: Ana Publications, 2006), 145; Henry P. Beers, American Naval Occupation and Government of Guam, 1898-1902, Administrative Reference Service, Report No. 6, Office of Records Administration, Department of the Navy, 1944, 21; “Proclamation in Guam: Capt. Leary, the Governor, Established American Sovereignty,” New York Times, August 30, 1899. ↩

- Tilley, “The United States in Samoa,” 1844-1845; E. M. Blackwell, Blackwell Genealogy, Book Two: Memoirs of Edward Maurice Blackwell (Richmond, VA: Old Dominion Press, Inc., 1948), 38-39; “Hoisting Our Flag at Tutuila,” Army and Navy Journal 37 (12 May 1900): 897. ↩

- “Hoisting of Old Glory at Pago-Pago,” Samoan Herald (Apia, Upolu), 21 April 1900, Despatches From United States Consuls in Apia, 1846-1906, T27, Roll 26, NARA-SB; “Hoisting Our Flag at Tutuila,” 897; Chiefs of American Samoa to B. F. Tilley, April 2, 1900, File: Deed of Cession, American Samoa Historic Preservation Office, Faga’alu, American Samoa; J.A.C. Gray, Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and Its United States Naval Administration (Annapolis: United States Naval Institute, 1960), 128.. ↩

- Program for Flag Day, “Ceremonies Attending the Hoisting of the American Flag in the Samoan Islands,” T27, Roll 26, NARA-SB; Blackwell, Blackwell Genealogy, 39; Tilley, “The United States in Samoa,” 1840; L. W. Osborn to David J. Hill, April 20, 1900, T27, Roll 26, NARA-SB; L. W. Osborn to Department of State (no name), May 1, 1900, T27, Roll 26, NARA-SB. ↩

- Tilley, “The United States in Samoa,” 1846; B. F. Tilley, “Development of Our Possessions in Samoa,” The Independent 53 (July 11, 1901): 1601. ↩

- Robert C. Kiste, “United States,” in Tides of History: The Pacific Islands in the Twentieth Century (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994), 245; David A. Chappell, “The Forgotten Mau: Anti-Navy Protest in American Samoa, 1920-1935,” Pacific Historical Review, 69 (2000): 223, 225; David J. Herdrich, American Samoa Historic Preservation Office, Faga’alu, American Samoa, to author, July 16, 2003. ↩

- Report of the Government of Tutuila, November 1901, File: Report of the Secretary of Native Affairs, 1901, Box 8, RG 284, NARA-SB; Blackwell, Blackwell Genealogy, 44. ↩

- Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall, 114, 117; Capt. Frederick J. Nelson, “Lieutenant William E. Safford—Guam’s First Lieutenant Governor,” Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute 78:8 (1952): 853-854; William Edwin Safford, Guam: An Account of its Discovery and Reduction, Physical Geography and Natural History, and the Social and Economic Conditions on the Island during the first year of the American Occupation (Washington: n.p., 1912), 16. When the Americans arrived on Guam, they changed the spelling of Agaña to Agana. Today, Agana is called Hagåtña. ↩

- Safford, Guam, 17, 27; William Edwin Safford, A Year on the Island of Guam: An Account of the First American Administration (Washington, D.C.: H. L. McQueen, 1910), 27, 107, 167. ↩

- Beers, American Naval Occupation and Government of Guam, 35; Safford, A Year on the Island of Guam, 34. ↩

- Darden, Historical Sketch of the Naval Administration of the Government of American Samoa, 22-23; General Study of American Samoa, General Report by Governor, 1940, Box 1, RG 184, NARA-SB; Barker, Cruise of the U.S.S. Abarenda, 10n3; E. J. Dorn to Mrs. Dorn, c1900, Box 2, Papers of Edward J. Dorn, Library of Congress (hereinafter cited as Dorn Papers). ↩

- F. W. Hackett to E. J. Dorn, June 6, 1900, Box 2, Dorn Papers; B. F. Tilley to E. J. Dorn, September 20, 1900, Box 2, Dorn Papers; B. F. Tilley to E. J. Dorn, November 22, 1900, Box 2, Dorn Papers; B. F. Tilley to Assistant Secretary of the Navy, March 26, 1901, Box 4, RG 284, NARA-SB; Blackwell, Blackwell Genealogy, 43. ↩

- General Study of American Samoa, Box 1, RG 284, NARA-SB; “Rough Journal of Commandant’s Office,” Box 1, RG 284, NARA-SB; J. F. Rose-Soley, “A Colonial Experiment,” Overland Monthly 38:3 (September 1901): 178. ↩

- As quoted in Roger’s Destiny’s Landfall, 114; Tilley, “Development of Our Possessions in Samoa,” 1601. ↩

- The Pacific American Foundation, www.thepaf.org, (June 16, 2003); “The Fita Fita Guard,” General Study of American Samoa, Box 1, RG 284, NARA-SB; Darden, Historical Sketch of the Naval Administration of the Government of American Samoa, 1-2. ↩

- “Proclamation to the Inhabitants of Guam and To Whom It May Concern,” as quoted in Beers, American Naval Occupation and Government of Guam, 22; “General Order No. 4,” August 25, 1899, in “General Orders Issued By The Naval Governor of Guam,” Guam Recorder 4:2 (1974): 50; Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall, 117, 119; Ens. C. L. Poor, “The Natives of Guam,” Harper’s Weekly 43:2243 (December 16, 1899): 29. ↩

- “An Ordinance Concerning Sunday,” November 5, 1900, Box 1, File: Regulations, Proclamations, and Orders of the Government of American Samoa, 1900-1906, RG 284 American Samoa Governor’s Office, NARA-SB. ↩

- Safford, A Year on the Island of Guam, 40, 123; “An American in Guam,” The Independent 51 (November 30, 1899): 3196; Beers, American Naval Occupation and Government of Guam, 29. ↩

- Blackwell, Blackwell Genealogy, 42; Malama Meleisea, Lagaga: A Short History of Western Samoa (Suva: University of the South Pacific, 1987), 109-111; For regulations passed by Commander Tilley, see United States Naval Station, Tutuila, List of Regulations and Orders forwarded to the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, October 29, 1902, File: (Regulations, Proceedings, Orders of the Government of American Samoa: 1900-1906), Box 1, RG 284, NARA-SB. See also, Darden, Historical Sketch of the Naval Administration of the Government of American Samoa, xiii, 20 and Gray, Amerika Samoa, 125-127. ↩

- Safford, A Year on the Island of Guam, 18; Nelson, “Lieutenant William E. Safford,” 855; Safford, Guam, 32. ↩

- Blackwell, Blackwell Genealogy, 32-33; Gray, Amerika Samoa, 132-134. ↩

- Safford, A Year on the Island of Guam, 109; Beers, American Naval Occupation and Government of Guam, 31. ↩

- Report on the Government of Tutuila, November 1901, Report of the Secretary of Native Affairs, 1901, Box 8, RG 284, NARA-SB; General Report by Governor, Rough Draft (2 of 2), Box 1, RG 284, NARA-SB; Blackwell, Blackwell Genealogy, 28; Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 56th Cong., 2d sess., 1900, H. Doc. 3, 18. ↩

- Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall, 121; P. Craig, “Mosquitoes, Filariasis & Dengue Fever,” samoanews.com, January 31, 2004; Gray, Amerika Samoa, 164-169. Filariasis continues to exist in American Samoa with thirteen percent of the 2002 population infected with it. ↩

- Safford, A Year on the Island of Guam, 79, 138-139; Carano and Sanchez, A Complete History of Guam, 406; General Order 13, January 23, 1900, “General Orders Issued By The Naval Governor of Guam,” 52; Gray, Amerika Samoa, 173-174; Darden, Historical Sketch of the Naval Administration of the Government of American Samoa, 34. ↩

- Safford, A Year on the Island of Guam, 67, 130-131, 164, 184; Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall, 122; ↩

- “American Samoa: A General Report by the Governor,” 1912, Box 1, RG 284, NARA-SB; Jordan and Kellogg, “Tutuila (U.S.),” 209; Gray, Amerika Samoa, 151-152; Benjamin F. Tilley to Charles Morris, June 19, 1900, Government Affairs, 1900-1901, Box 4, RG 284; NARA-SB; Benjamin F. Tilley to Assistant Secretary of the Navy, May 7, 1901, Government Affairs, Box 4, RG 284; NARA-SB; Captain U. Sebree, “Progress in American Samoa,” The Independent 54 (November 1902): 2814-2815. ↩

- Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall, 120-121; Nelson and Nelson, The Island of Guam, 158; Beers, American Naval Occupation and Government of Guam, 36. ↩

- Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall, 121; Beers, American Naval Occupation and Government of Guam, 36-37; Safford, A Year on the Island of Guam, 143-144, 148, 154. ↩

- Norma E. Hacker, ed., Charles E. Barker, Cruise of the U. S. S. Abarenda, “Collier,” 1899 (n.p.). ↩

- “Memo of a conversation with Comdr. B. F. Tilley on 17 May 1901,” File: General Correspondence, 1901, Box 3, Dorn Papers; E. J. Dorn to the Secretary of the Navy (John D. Long), May 17, 1901, File: General Correspondence, 1901, Box 3, Dorn Papers. ↩

- Charles Keeler , “A Blot on Our Insular Rule,” New York Evening Post, October 23, 1901; Charles Keeler to H. J. Moors, August 26, 1901, Box 3, Dorn Papers; H. J. Moors to Charles Keeler, September 7, 1901, Box 3, Dorn Papers; H. J. Moors to E. J. Dorn, September 7, 1901, Box 3, Dorn Papers. ↩

- “Samoans to the President,” New York Times, March 20, 1901, 6:2. ↩

- Gray, Amerika Samoa, 135-137; “Capt. Tilley Under Charges,” New York Times, October 10, 1901; “Rear Admiral Benjamin Franklin Tilley, USN,” Factsheet, Early History Branch, Naval Historical Center, Washington, D.C. ↩

- Evans, An Admiral’s Log, 10, 14-16; Blackwell, Blackwell’s Genealogy, 51; Gray, Amerika Samoa, 138; F. W. Hackett to Commandant, Navy Yard, Mare Island, October 8, 1901, Letterbook, July 10, 1901-June 20, 1902, Box 15, RG 181, NARA-SB; F. W. Hackett to Commandant, Navy Yard, Mare Island, October 7, 1901, ibid. ↩

- Pacific Station, year 1901, General Court-Martial, Order No. 10, U.S. Flagship Wisconsin, Pago Pago, Tutuila, Samoan Is., November 15, 1901; Evans, An Admiral’s Log, 11-12, 17; Blackwell, Blackwell Genealogy, 51-52; “Capt. Tilley Exonerated,” New York Times, December 3, 1901, 9:4. ↩

- Petition, Samoans to United States Navy, c 1903, Mss 49171, Papers of the United States Navy, Collection 1899-1903, Library of Congress, Washington, D. C. ↩

- Beers, American Naval Occupation and Government of Guam, 35; “Capt. ‘Dick’ Leary Dead,” New York Times, December 28, 1901; William B. Cogar, Dictionary of Admirals of the U.S. Navy, Vol. 2, 1901-1918 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989), 284; “Death of Admiral Tilley,” Washington Post, March 19, 1907. ↩

4 Responses to Two Captains, Two Regimes: Benjamin Franklin Tilley and Richard Phillips Leary, America’s Pacific Island Commanders, 1899-1901