Ulrich van der Heyden

University of South Africa, Pretoria

German War Crimes during the First World War?

Even a hundred years after the beginning of the First World War, 1 some segments of the German media still glorify submarine warfare as having been the “seminal catastrophe of the twentieth century.” These accounts bluster about gross register tons sunk by German U-boats. They embed that force in a hagiographical narrative, 2 and by way of advancing counterarguments against various accusations, speculate about international law violations, especially by British naval forces against German citizens. 3

At the same time, some popular history magazines and journals, wishing to draw on public interest, deny or play down German war crimes during the First World War. For all that, the German crimes contravening the international conventions of war cannot wholly be denied. Germans committed war crimes that are, for the most part, well documented.

After the end of the First World War, the Allies put around 890 Germans on a war crime list, starting with the German Kaiser, to generals and admirals, right through to officers of various ranks and even to several ordinary soldiers. Wilhelm II escaped prosecution by fleeing and seeking asylum in the Netherlands; others, indeed the vast majority of the alleged war criminals, followed suit. By doing so, they tried to abdicate their responsibilities. However, one or two cases did reach the German public after the end of the war, primarily pushed by articles in the Allied press. Such reports generally elicited astonishment and skepticism among the population that had lost the war. The publicized crimes contradicted the noble image of German soldiers, who were said to have lost the war only because the “November Criminals” back home had stabbed them in the back.

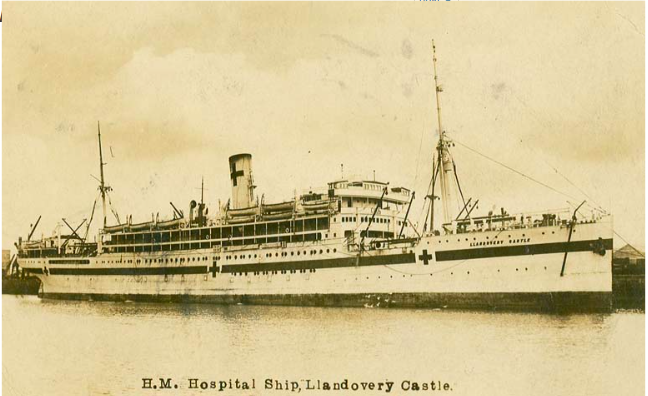

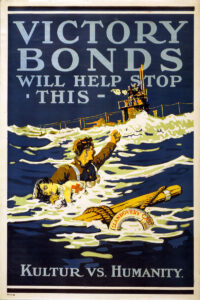

A 1918 Canadian propaganda poster used the sinking of Llandovery Castle as a focal point for selling Victory Bonds

(Montreal, Montreal Litho. Co. Ltd., [1918]; Library of Congress)

War criminals of the Second World War were turned in by those who had lost the war. They were subsequently tried before Allied courts at Nuremberg and follow-up trials. Those accused of war crimes in the First World War suffered no such consequences. On the contrary, only a few had to stand trial before German judges; none before an Allied court.

One of the few sailors who were accused of war crimes was the commander of the German U-boat, U-86, Helmut Patzig. 5 He had, after the Treaty of Versailles, evaded punishment for his war crime by fleeing and assuming the surname of Brümmer. By changing his name, he hoped that he would not be tracked down and held accountable for his crime. 6

The First World War – The Career of a Young Naval Officer

At the beginning of the First World War, when the Imperial German Navy (Kaiserliche Marine) joined the battle at sea with twenty-eight operational U-boats, its commanders generally adhered to the rules of naval warfare that were in place at that time. The U-boat force proved to be an effective instrument. When hostile warships were sighted, they were, if the situation allowed it, attacked without warning. The problem with merchant ships was different. Here the Rules of Prize Warfare applied, as laid down by international treaties. Conventions of the time meant that when a U-boat sighted an enemy merchant ship or a neutral vessel suspected of supplying the enemy with goods or military equipment, the U-boat could call the suspicious vessel to halt, search it, and, if necessary, sink it. This procedure proved to be increasingly risky for the Imperial German Navy, as other ships could meanwhile come to the assistance of the boarded vessel, or the purported merchant ship (Q Ship) turned out to be a U-boat trap. The Germans lost several submarines in this manner.

As a result, the German Admiralty proclaimed “unrestricted submarine warfare,” which meant that merchant vessels were treated as warships and attacked without prior warning. Doing so was a violation of international law, but the practice was probably obeyed by all German U-boat commanders. The German Navy High Command informed the “seafaring nations of the world in an insolent manner” that the waters around Great Britain and Ireland, including the English Channel, were war zones. Starting 18 February 1915, they would destroy any enemy merchant vessel found in this area. Further, it would not be possible in each case to avert the dangers faced by the crew and passengers. Germany also warned that ships sailing under a neutral flag also ran the risk of being sunk. 7

In May 1915, the German submarine U-20 torpedoed the Lusitania, during which 1,200 people lost their lives, including 128 American citizens. 8 This violation of maritime law led to increased calls in the USA to become actively involved in the war against Germany.

The German Reich Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg wanted to avoid the involvement of American troops in the hostilities in Europe at all costs. He, therefore, demanded that the German U-boat force should again engage in battle according to the Rules of Prize Warfare. Naval authorities widely criticized this action, as the Admiralty was confident that Great Britain would, amid a continued and unrestricted submarine warfare, capitulate within six months. The leading military officers on land (i.e., the Supreme Army Command, too), apparently still saw opportunities in bringing the deadlocked hostilities on the European continent to a victorious conclusion with an intensification of naval warfare. For this reason, the military commanders opposed Wilson’s demand. They could assert themselves at least to some extent. In some regions of the Atlantic, to wit, Germany continued to adhere to the practice of unrestricted or, as they called it, intensified, submarine warfare. Except for passenger liners, all enemy merchant ships in these areas could be attacked and sunk without warning.

As the literature has documented, the general war situation in late 1916 had deteriorated to such an extent for Germany that, on 1 February 1917, the German Navy resumed its all-out unrestricted submarine warfare, torpedoing Allied merchant ships without warning. 9 The outcome of this policy was that the USA declared war on Germany and its allies on 6 April 1917. American entry into the war brought about a decisive change in the balance of power, favoring the Entente.

At first, the German Navy sunk a record number of ships. By summer, however, reports of German U-boat successes had already began to dwindle. 10

Many career-driven captains desired to earn their stripes by sinking more tonnage during the final year of the war, a fact which frequently remains undisclosed in naval history. “Patriotic sentiments and a spirit of solidarity” were to be encouraged through the “benefits of material nature.” 11

However, this policy could not hinder the USA (apart from supplying a substantial amount of war materials) from entering the war at sea and, in a sustained manner from 1918 onwards, joining the Allies in land warfare. The German Navy could not prevent a single American troop carrier from shipping soldiers and military equipment onto Western Europe. Around 1.4 million US soldiers reached Western Europe, voyaging across the ocean unchecked.

A German Career in the Navy

During the First World War, Helmut Patzig, born 26 October 1890 in Danzig/Gdansk, served as executive officer, first on a submarine with the designation UA 12 and then on U-55. He had joined the Imperial Navy in April 1910 and served as acting sub-lieutenant (Leutnant z.S.) from 27 April 1913. At the start of the war, he was on board the battleship Pommern. Then he transferred to U-boats. He was promoted in March 1916 to first lieutenant (Oberleutnant z.S.).

On 26 January 1918, Helmut Patzig took command of U-86. This submarine was a standard German U-boat of mid-range, which was to “earn the sad distinction,” 13 as stated in current work on the history of the First World War, of sinking the hospital ship Llandovery Castle in defiance of maritime law.

What had happened? Helmut Patzig was regarded by his superiors as an ambitious officer and was popular among his subordinates. He had received the Iron Cross Second- and First class in May 1916 and March 1917. Decades later, “his” crew related stories of the cooperative interaction between them and “their” commander, who did not consider himself to be too good to lend a hand if, for instance, there was a technical problem with one of the U-boat’s engines. They believed he had saved the submarine and its crew by personally intervening with the repair of a faulty engine while being submerged. This story explains why so many crew members stuck to “their” commander, even after the war. Not one of them testified against him in court.

Under his command, U-86 successfully conducted ten documented operations against the enemy in the eastern North Atlantic around the British Isles. 14 Scholars cite thirty-two sunken merchant ships for U-86, with an overall tonnage of up to 119,000 gross register tons. 15 Among these ships were some who had sailed under a neutral flag.

The War Crime

On 27 June 1918, when an erstwhile British passenger and mail ship, the Llandovery Castle (named after a Welsh castle ruin), clearly marked as a hospital ship, was heading towards the Irish coastline, the people on board were feeling entirely safe, for the British government had informed all countries engaged in warfare that it had commissioned the ship, previously also deployed as a troop carrier, into the medical service. Coming from Halifax, Canada, the ship had 164 crew members on board and an additional eighty Canadian medical doctors and orderlies, and fourteen Red Cross nurses.

When the sun sat on the horizon that day, the sea was calm. Nobody feared any perilous surprises by German ships or U-boats. It was prohibited by international law to attack vessels and facilities with Red Cross identification. Several distinct red crosses were visible on the brightly lit ship.

However, the sense of calm and safety was deceptive. For hours already, a German U-boat had been tracking the 622-berth hospital ship. The U-boat was U-86, the submarine under the command of First Lieutenant Helmut Patzig. During the previous night, the U-boat had torpedoed the British steamship Atlantia out of a convoy. Two shipwrecked crew members from the sunken ship were taken on board the U-boat as prisoners. 16 Why Patzig would track the Red Cross ship in the first place remains unknown. The lawyer and author Friedrich Karl Kaul, who was the first to examine the files, provides a plausible explanation. He puts it down to the character of the commander:

At first, U-boat commander Patzig himself probably did not know why he was now tracking the ‘Llandovery Castle.’ The hospital ship could not really be considered as a quarry. Not really! But what if the Red-Cross-painted ship was carrying war equipment or relatives of combat units onboard? After all, German authorities were constantly alleging that, contrary to international law, the Yankees and Brits were camouflaging their war carrier vessels! If he, Imperial First Lieutenant Patzig, could succeed in providing the evidence for this violation of international law by hostile Allied forces – he would be sure of the ‘Pour le Mérite,’ the highest German war decoration, but at the very least the long-yearned-for appointment as Lieutenant-Commander (Kapitänleutnant). 17

Even though Patzig could see that the ship in question was a hospital ship, he disregarded the misgivings voiced by his officers and attacked the Llandovery Castle.

Later, the officers and part of the crew would indeed use the excuse – spurred on by the German national press – that the ships of the Entente frequently camouflaged troop and ammunition transports as hospital ships. The vessel that had come into Patzig’s sights could, as he later offered by way of justification, also have adopted a Red Cross camouflage. He must have firmly believed this to be the case. Around 2130, the commander of U-86 ordered two torpedoes to be fired. One of the torpedoes missed its target. The other one hit the engine room on the port side. It took less than ten minutes for the ship to sink after it had broken in two. The torpedo had hit the ship’s boilers. According to credible testimonies, the officers and crew of the U-boat looked on in shock as the unarmed crew, together with the nurses and medical doctors, hurried to climb into one of the Llandovery Castle’s nineteen lifeboats. At least two lifeboats pitchpoled during evacuation. Most of them had either been destroyed by the explosion or capsized. Three lifeboats managed to get afloat. The ship’s captain, Edward Arthur Sylvestre, was in one of them. Those afloat now began pulling other survivors onto their lifeboats.

Llandovery Castle by George Wilkinson (Peace and War in the 20th Century Collection, McMaster University)

The German U-boat had meanwhile surfaced for rescue operations. Lieutenant-Commander Patzig ordered the rescue of the shipwrecked to be halted. The lifeboats had to go alongside. Patzig interrogated the surviving captain and several officers of the sunken ship. It now became unequivocally clear to him what he had done, of what crime against maritime law he had made himself guilty. For the time being, he let the lifeboats go on their way. 18

But then Patzig must have taken fright. It became clear to him that he had committed a war crime, to which there were witnesses. He ordered his boat to be turned around and went back to the scene of his crime. He ordered the helmsman to bear down on the lifeboats and to ram them. But they could narrowly escape the attacking iron monster, at which point Patzig gave the command, “clear to dive.” The crew subsequently went below deck. Only Patzig remained on deck, together with the two watch officers, John Dithmer and Ludwig Boldt, as well as Chief Petty Officer Meißner, who was the gunner in charge of the stern gun.

Apart from the above mentioned individuals, Patzig did not wish to have any more witnesses to the heinous deed that was about to be committed. He was afraid that even his comrades – after knowledge of it had possibly become public – would deem it to be criminal. He ordered the gunner to fire at the lifeboats. They hit one, sinking it. The British and Canadian mariners and medical practitioners, just spared from drowning, now lost their lives after all. Only one lifeboat, containing Captain Sylvestre and twenty-three other survivors, could escape to the coast 116 miles away, despite the intense pursuit by the U-boat and its resumed ramming attempts. Two hundred thirty-four (234) people nevertheless fell victim to the war crime committed by the German U-boat commander Helmut Patzig.

However, he was unaware of one fact that did not come to the knowledge of the investigators, prosecutors, appraisers, and judges: namely, that one of his devoted crewmembers, the helmsman, a simple seaman, had, contrary to his commander’s orders, opened a porthole in the conning tower and witnessed everything. Out of camaraderie or a certain reverence, he was reluctant to cause his superior any harm, and later also did not present himself as an eyewitness to the courts. The exact reasons for his behavior are not known. Was it only misplaced camaraderie or team spirit, or was it fear? After all, the gunner, himself, had died under mysterious circumstances after the war.

No doubt, the eyewitnesses were reluctant to speak. The entire crew, officers and seamen alike, had to promise their captain to keep their silence about the sinking of the hospital ship and the lifeboats. What had happened, Patzig said, he only had to justify his actions before God and his conscience. He then tampered with the logbook, entering a route that his submarine ostensibly took, a long distance away from the scene of one of the worst war crimes of the First World War. As his crime remained hidden, for the time being, Commander Patzig, upon his return to Wilhelmshaven, received a congratulatory telegram from Kaiser Wilhelm II, which read: “Bravo to the valiant commander.”

An Attempt at Atonement

Shortly after arriving at the base, U-86 was taken to the dockyard as it had struck a mine. Patzig was transferred and became the captain of U-90, which he commanded until the end of the war. 19 At his request, the helmsman from his old crew was also transferred to the new U-boat. At the end of the war in 1919, both men were dismissed from the Navy. Even after his release from the service, Patzig was promoted to Lieutenant-Commander, retired. It is highly unlikely that his superiors were unaware of his crime. After all, the lifeboat survivors had informed the public of their ordeal. The war crime had elicited a regular storm of outrage on a global scale. Friedrich Karl Kaul, who was a prominent lawyer in East as well as West Germany, assessed the situation in a rather detailed article on the subject: “A hospital ship, clearly marked as per regulations of the 10th Hague Agreement, had been torpedoed! Its shipwrecked passengers had been fired at in open lifeboats, killing all but twenty-four! That constituted an accumulation of international law infringements at a level the Imperial German Navy had hitherto not dared to carry out.” 20 The Allies put Patzig’s name on the war criminals’ list.

According to the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, the victorious powers would bring German war crimes to trial. Amongst others, the British government wanted to put three U-boat commanders on trial who had allegedly sunk hospital ships. Upon receiving the knowledge of this development, Patzig fled Germany. His name headed the line-up on the so-called “probationary list” of punishable war crimes. The fact that he was hiding abroad indicates how profoundly conscious he was of his punishable deed. South America, Danzig/Gdansk, and the Baltic countries were suspected as being his possible whereabouts; others claimed to have seen him in Sweden or Denmark. It remained a mystery at that time as to where he actually was. Current research has established that he was hiding in the Baltic capital of Riga. 21

Patzig’s possible whereabouts and fate even occupied the cabinet meetings of the Reich Chancellor Joseph Wirth. Thus, when a report surfaced in July 1921 that Patzig had allegedly been arrested in Denmark, it was decided “that, if the report was accurate, everything should be done to obtain the extradition.” 22

The preoccupation of the highest German government offices with the Patzig case also gave cause to concentrate on an “inverse list,” which was raised in public to implicate the victorious Allies of violations of international law. Such public accusations were usually met by approval in the German press, thereby contributing towards strengthening of nationalistic tendencies in the political sphere and the population in general.

The victorious powers took careful note of these developments and threatened to litigate against those responsible for German war crimes themselves. The German minister of justice, Eugen Schiffer, was instructed by the cabinet to ensure that the “inverse list,” advanced by certain politicians of the Weimar Republic as a vehicle for anti-British propaganda, would not be published. As a result, concurrently planned political actions got delayed. Minister Schiffer subsequently wrote a “private letter” to the president of Württemberg, Johannes Hieber, who was an essential supporter of those who wished to hold a mirror up to the Allies. In it, he said, “The government of the Reich shares the view that the one-sided condemnation of German war criminals is immoral, which is justifiably experienced by popular sentiment as being a brutal violation of any sense of justice. It is therefore determined, as soon as an appropriate time presents itself, to demand equal treatment of foreign war criminals, for which the inverse list shall be used as the basis. However, for the time being, it deems this moment not to have arrived.” 23

Agitation within the German populace and its politicians had already begun by the time the representatives of the Entente abnegated their right to refrain from demanding the extradition of Germans accused of war crimes. The Allies were entitled to demand extradition according to the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles. The hope was that doing so would appease the anti-British and anti-French voices in German society. The condition set down by the Allies for the indictment and conviction of German war criminals by the German judiciary was that the Reichsgericht (Supreme Court) in Leipzig was to conduct these trials. The German government had pledged its compliance in this regard. Germans could thereby sit in judgment over Germans.

The victorious powers and Reich government were fully aware that, if the parties concerned had insisted on the arrest and transfer of those Germans who should be hunted down and convicted, the possibility of unrest or even an uprising could easily have led to civil war. 24

It is fair to assume that extradition of Patzig to the Entente powers would have acutely and profoundly fueled the explosive atmosphere in Germany during the early years of the Weimar Republic. Public opinion was, to a large extent, informed by discussions of the “Erfüllungs” and “Katastrophen” politicians (‘appeasement’ and ‘catastrophe’ politicians) who rejected the conditions stipulated by the Treaty of Versailles. Petty bourgeois jingoism and chauvinism were characteristic features of Germany at that time.

The possibility that an intensified discussion of war crimes committed by the Allied forces could equally have come up in the event of mutual recriminations may also have been a reason for the Allies to cede the punishment of crimes committed during the war to their former enemy. It is for this reason that the Allies refrained from prosecutions through their judicial institutions; thus, the trial took place before the German Reichsgericht in the Saxon city of Leipzig. The Constituent National Assembly, together with the Reichstag (Parliament of the Reich), had provided the legal basis. The specially drafted “Act for the Prosecution of War Crimes and War Offences” was unanimously adopted. And so the “Leipziger Prozesse” (Leipzig trials) began. During the upcoming proceedings and sentencing, the only law that was to be applied would be German criminal law.

Based on the new act, the chief Reich prosecutor issued a total of 1,803 lawsuits, of which only thirteen went to trial. The remaining cases did not advance beyond investigation proceedings. Of the thirteen trials, only nine reached the sentencing stage; of the twelve men accused, only six were convicted. 25

Helmut Patzig was to be one of the first to stand trial, but he remained elusive, and only two U-86 officers were arrested. However, Dithmer and Boldt, were on none of the lists that the Allies had handed over to the German authorities. Nevertheless, the chief Reich prosecutor saw that they were put behind bars, and issued an arrest warrant Patzig. The German judicial authorities wished to demonstrate that they were serious about autonomously prosecuting the war crimes committed by citizens of the Reich. Based on the statements of several U-86 crew members, the chief Reich prosecutor concluded that both watch officers were under suspicion of having been complicit in the shelling of the lifeboats. 26 This reasoning was that after the sinking of the hospital ship, the main suspect had “intentionally killed quite a large number of British officers and crew members, as well as several members of the Canadian Army Medical Corps and several nurses, and had willfully executed the killings” (“…vorsätzlich eine größere Anzahl von englischen Offizieren und Mannschaften sowie eine Anzahl von Angehörigen des Canadian Army Medical Corps und mehrere Pflegerinnen vorsätzlich getötet und die Tötung mit Überlegung ausgeführt…“) 27

The trial had attained top political priority. Friedrich Karl Kaul explained the background for the charges brought against the two navy officers:

It was not possible to demonstrate their goodwill with the example of one of the prominent figures, nor was it in their (the Reich government’s – UvdH) interest. And so an understanding was reached between the Reich Ministry of Justice, headed at that time by the Social Democrat Radbruck, and the gentlemen in red robes to use the case of the two navy officers, both unknown to the public, to serve as an ‘example.’ Moreover, the criminal charge brought against them … was virtually without equal in the history of maritime warfare. 28

The indictment, dated 11 June 1921, accused John Dithmer and Ludwig Boldt of having killed an unspecified number of shipwrecked passengers. It, therefore, called for an initial charge of murder. 29 After all, Patzig had also been charged with murder in absentia. The court questioned witnesses in great detail. The court established that the two officers had participated in the actions concerned in the hearing. The accused men were not charged with violating international law by having sunk a Red Cross ship. Firing on shipwrecked passengers was the accusation. This act did not constitute murder, according to the court. The court deemed it to be manslaughter based on consultations with “experts” who described many cases. The accused men remained mostly silent, complicating the matter. The trial commenced in Leipzig on 12 July 1921. During the proceedings, sixty-three witnesses were called – among them, four survivors of the sunken hospital ship. The evidence established that U-86 had torpedoed and sunk the Llandovery Castle on 27 June 1918. Crew members had fired on the lifeboats with an 8.8-cm stern gun to eliminate the eyewitnesses. During the main hearing, no evidence could be found, of course, of the direct participation of the accused watch officers in the murder of defenseless civilians. Not one of the questioned German crew members could confirm this fact, as they had all gone below deck by order of the commander. 30

Besides the two accused officers, there remained the fugitive commander and the gunner. The latter, however, had died. Presumably, the chief petty officer did not die a natural death. 31 There were no other eyewitnesses who came forth to testify in court, as the helmsman had not revealed himself as such.

The course of the trial, which was closely followed by journalists of a broad political spectrum from various countries, proved to be unsatisfactory for the surviving Allied witnesses to the heinous deed. The British, Italian and American press, in particular, criticized the fact that the accused U-boat commander evaded his responsibility by having absconded, and attacked the German authorities for not launching an intensive search for the main accused. Observers of the trial criticized, with equal intensity, the two officers for their silence. Both refused to make any statement. According to Walter Schwengler, who made an in-depth study of the trial, the remaining crew members of U-86 “were unable to give any evidence about the target that had been taken under fire, since they had, as per instruction, been ‘on the diving station;’ in other words, inside the submarine.”

Only the helmsman, who had somehow peered out of the conning tower, had been a mute observer of the deed. And he remained silent: probably out of fear of the aggressive noises made by the nationalist press, and most certainly also out of a spirit of camaraderie. It was only in his old age, and within his family circle, that he spoke out about what he had observed. He related, among other things, how Patzig pushed the gunner aside as he was firing on the lifeboat. The reason for this is not known: was it because the gunner intentionally missed the target, was the cannon intermittently malfunctioning, or did the gunner refuse to obey the firing order due to a crisis of conscience? Patzig tried to kill the shipwrecked passengers himself. 32 This incident eventually led the helmsman – albeit rather late and despite the veneration the seaman held for his commander – to a critical evaluation of his superior whom most crew members had held in high esteem 33 , and to speak about it to his family after more than forty years.

Another matter that never emerged in court was the other method employed by Patzig; namely his elimination of witnesses in the lifeboats by ramming them with his U-boat. Only the commander and the helmsman knew about this, as Patzig had ordered hands to clear the command center. This command-style complicity – or rather connivance – placed the seaman under psychological stress. The images of shelling and hunting the lifeboats remained with the helmsman for the rest of his life.

As he subsequently did not testify in the Reichsgericht, the helmsman’s observations were not part of the evidence for the trial. Since Patzig, the main accused, had not handed himself over to the courts, his account would have made little difference anyway. Thus, the two officers of U-86 were each sentenced to a prison term of four years as having been accessories to manslaughter, because they had safeguarded the artillery shelling of the lifeboats through their monitoring activity. The accused nevertheless admitted no culpability where their actions were concerned. They believed that they had only followed orders and had merely scanned the horizon for enemy ships. They were unwilling to testify on the “events themselves.” As the accused Boldt put it, he was “bound to his commander by a promise to remain silent;” a promise he still felt obliged to keep. 34

Although the two officers refused to testify, prosecutors nevertheless claimed limited success. The prosecutors believed they had made a point of identifying those responsible for monitoring the horizon, thereby having aided and facilitated shelling of the lifeboats. The indictment charged, “…that they had, by being on the look-out, guarded against any threat to the U-boat from the enemy and, by doing so, had created the possibility for Patzig to proceed with his course of action against the lifeboats in the first place.” 35 The Reichsgericht furthermore ruled that Dithmer be dismissed from service and that the right of Boldt to wear his uniform be rescinded.

The sentencing of the two officers of U-86 was greeted with a certain amount of satisfaction by the Foreign Office because Britain had meanwhile reacted with increasing distrust concerning the seriousness with which the Leipzig war crimes trials were conducted, especially in light of the Patzig case. Now the Foreign Office could present, if not the main accused, then at least the sentencing of two suspects, the identification and prosecution of whom had been due to German investigative activity, something which “was noted with quiet satisfaction as proof of judicial impartiality.”

Several other questions arise retrospectively. What would have happened if the silent eyewitness helmsman had testified in court? What if the lawyers had proved that Patzig operated the gun that was supposed to sink the lifeboats? Or that he had intended to ram the lifeboats with the U-boat, a matter never raised during proceedings? How would the Allies have reacted, had they been made aware of such blatant, verifiably multiple violations of maritime and international law? Would they have demanded Patzig’s extradition to prosecute him themselves? How would the German government have reacted? And the German public? The former enemies? Would the witness’s life been in danger from right-wing nationalist forces? Had the helmsman therefore prevented an international conflict by remaining silent? 36

Reactions to and the Significance of the Trial and its Outcome.

Examining the attempts at atonement for war crimes committed by the Germans during the First World War heard in court in the early 1920s leads one to agree with Frank Neubacher that the results were poor, 37 especially if one considers the ratio of initiated lawsuits to those that resulted in a conviction. The balance was, after all, 1803 to 6.

A contributing factor was that, with time, the energies of the judges in Leipzig to prosecute such crimes began to lag, especially when the interest shown by the Allies in this regard also began to wane. The judges discontinued many proceedings. Only a few of those sentenced had their convictions enforced.

When the chief Reich prosecutor, Dr. Ludwig Ebermeier, had to read out the bill of indictment against the officers of U-86, he gave eloquent testimony to the attitude of the German judiciary towards the war crime hearings. He began by saying: “Hardly ever during the nearly forty years that I have been serving as a state prosecutor and a judge, has the performing of my official duties been more difficult than today, where I am compelled, due to the outcome of the three days of hearings that lie behind us, to bring charges against two German ship officers … for the most serious crime listed in the German code of law.”

He then proceeded to give a relatively faithful rendition of the course of events. In his account, he did not, however, accuse Patzig of torpedoing a hospital ship, but merely of attempting and executing the killing of defenseless, shipwrecked passengers. According to the chief Reich prosecutor, the accused, Boldt and Dithmer, assisted in the killing of the shipwrecked passengers and had “acted with premeditation.”

Leading representatives of the German Naval Command, such as the Commander in Chief (Submarines), Vice Admiral Andreas Michelsen, for instance, challenged the legitimacy of the trial in publications and lectures on the topic. 38 Along with other high-ranking German military officers, Michelsen acknowledged how reprehensible Patzig’s actions and commands were. Michelsen recognized that in “removing” witnesses, Patzig had attempted to “conceal” his deed. Patzig wanted to “prevent news of this matter from reaching Britain,” as pointed out in the judgment of the court. 39

It appears as though the judiciary acknowledged this argument as being some excuse for the killing of unarmed civilians. That is the only plausible explanation for the fact that the sinking of the Llandovery Castle was manifestly considered to be a violation of international law, but had not been made the actual subject matter of the trial. 40

For the victims, the outcome of the legal proceedings was far from satisfactory. The significance of the trial lies not in the lenient sentences handed down for sinking the hospital ship or the cowardly attacks on the lifeboats. Nor is it significant for the small number of punishments meted out to those Germans who had committed crimes that violated international law. The real significance of the trial was that in the future, individuals would be held accountable for their actions in wartime by the standards of international law. 41 It was furthermore clarified for the first time in Germany that a military subordinate’s duty to obey, and recourse to its subjective viewpoint, is not unconditional but rather subject to objective evaluation. 42

An essential lesson of the Leipzig trials was that proceedings against war crimes must in the future not reside in the hands of a national judiciary, but that they instead require an international criminal court. Thus, the formation of the United Nations’ International Court of Justice in The Hague grew out of the experiences acquired and lessons drawn from the Leipzig trials. 43

From the viewpoint of legal history, the Leipzig trials, which were conducted solely on account of German war crimes committed during the First World War, led to necessary reforms concerning the conduct of war crimes trials subsequently held at Nuremberg and Tokyo after the Second World War.

For this reason, in academic publications, the Leipzig trials are sometimes referred to as the “prologue to Nuremberg.” 44 At the Nuremberg trials, nobody wanted to repeat the same mistake made with the Leipzig trials, having resulted as they did from the Treaty of Versailles. The central aspect of this mistake was that terms of the treaty were dictated to and imposed upon a defeated Germany after the First World War. Subsequently, German authorities were left to prosecute and sit in judgment over their own war criminals.

A Slapstick Farce instead of Punishing a Rare Crime

“Many things were not done strictly in accordance with the rule of law, back then in Leipzig,” the lawyer Harald Wiggenhorn, one of the most renowned experts in the events analyzed here, concluded. 45 In his book, he demonstrates that the Ministry of the Reichswehr (Army of the Reich) and the Reich Ministry of Justice were playing a double game. On the one hand, they investigated the crimes awaiting trial, but, on the other, they made funds, defense lawyers, and additional support available to the accused, to assist them and delay the proceedings.

For this reason, later experts on the subject classified the Leipzig trials as being a “parody, comedy and scandal” or, as Gerd Hankel, an expert in international law who also made a meticulous study of the Leipzig trials, rates them – and probably justifiably so –, as a “Schmierenkomödie” (slapstick farce) 46 .

An indication of the mood among the German people, mainly where the Patzig case was concerned, is that the courtroom erupted into turmoil when verdicts for the two officers, Boldt and Dithmer, were announced. After the sentencing, the two convicted men received written demonstrations of sympathy from various quarters, as high up as the Reichswehr and Navy Command.

And the two convicted men did not have to spend too much time in prison either. As early as 17 November 1921, Boldt escaped from a jail in Hamburg. On 29 January 1922, Dithmer was broken out of jail in Naumburg/Saale by several men who would later be part of the group that murdered Reich Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau. 47 Both absconded abroad. Dithmer worked in a bank in Barcelona, and Boldt founded a company for electrical systems in Cali (Colombia). Subsequently, German public interest in this “case” largely disappeared.

Even after the sentences, German politicians discouraged, as far as possible, any kind of public discussion of the matter. However, the war crime at sea, and the attempt to bring the culprits to justice, was not entirely swept under the carpet in the Allied press. In Britain, open criticism was publicly levelled at the verdict for months afterward. The sinking of a ship sailing under the banner of the Red Cross, together with attacks on the lifeboats, was considered a clear case of mass murder. 48 Conduct of the proceedings also elicited frequent criticism. It had been, as per a letter from the chief Reich prosecutor to the Reich Minister of Justice, rather difficult to appease the British government after the “escape of Boldt and Dithmer.” 49

In 1925, a request for pardon for the two convicted men from U-86 was raised in the Weimar Republic. Authorities denied the request because such an action would spark criticism abroad. 50 A “deep concern” was expressed that an amnesty could “possibly bring about a revival in the abating propaganda of wartime atrocity in countries abroad.” 51

However, in 1926, the arrest warrant for Helmut Patzig for committed war crimes was unexpectedly rescinded by order of the chief Reich prosecutor. The reason cited for this decision was that “pressing grounds for suspicion no longer exist;” that he had committed “the crimes he has been charged with.” 52

The recorded files provide information about the struggle that went on behind the scenes in the Patzig case. The whereabouts of Helmut Patzig was still unknown to the German authorities. However, the political climate in the country had meanwhile produced a groundswell of nationalistic sentiment. Patzig no longer had to fear extradition or facing a lengthy prison sentence if he were to stand trial in Leipzig. The rescinding of his arrest warrant was proof of this.

The reason for this unexpected decision was a “statement of facts” and “explanation” dated 26 July 1926, which Helmut Patzig handed to his lawyer for the court. 53 In it, Patzig gave an account of his version of the incident and attempted to explain why he had torpedoed the Llandovery Castle and ordered his men to fire at the lifeboats. He argued that he had aimed to sink a troop carrier, because otherwise – such was his reasoning, dripping with self-conviction – he may have been “blamed for the outcome of the war itself.” 54 Besides, the lifeboats were, according to him, “filled with soldiers, who would go and stand among enemy ranks again.” 55

The conclusion Patzig drew from his crime against maritime law is downright terrifying: “Today I am of the opinion that, if I should be faced with similar conflicts, I would be obliged to follow a similar course of action.” 56 After having taken note of Patzig’s statement, the Reichsgericht complied with the request of his defense counsel to reopen the proceedings.

After receiving Patzig’s justification, the courts also granted a respite of the execution of sentence to Dithmer and Boldt, a search for whom had been ongoing since their escape from prison. The grounds for punishing their flight were thereby beyond judgment.

In 1928, after further expert evaluations – even one on Patzig’s “statement of facts” – had been issued, the non-public proceedings that followed this course of events recommenced before the Leipzig court. 57 The result was that, on 4 May 1928, the two officers were cleared of all charges, seeing that their commander, Helmut Patzig, who had emerged from the shadows, had generously taken sole responsibility for the incident. Upon reading the “statement of facts” of the commander of U-86, as well as an “explanation” drawn up by him on the same day, 58 one may discern the beginnings of doubt where his actions are concerned – provided that he was sincere. But then he went on to say: “There was no point in racking one’s brains over what happened.” 59

The arrest warrant issued for Patzig was rescinded. Indicative of changing public attitudes in Germany, proceedings against the commander and the two officers from U-86 concluded after they responded to questions put to them by the Reichsgericht in Leipzig. 60 Further, the proceedings were placed on hold for a protracted period until, based on the so-called depenalisation laws of 1928 and 1930, their legal cessation took place. Boldt and Dithmer were even awarded financial compensation for the period spent on remand and for the partially enforced sentence. 61

One may accept Walter Schwengler’s argument, which concludes that the responsible judges did “not observe their statutory obligation” in “pursuing Patzig’s arrest and sentencing.” With no judgment delivered against Patzig, however, the proceedings were, at least in strictly legal terms, concluded. Eventually, on 20 March 1931, the criminal division of the Reichsgericht closed the proceedings against Kapitänleutnant, retired, Helmut Patzig permanently.

This action, which made a mockery of the victims, did not create a great stir. An Allied commission to investigate the Leipzig trials did admittedly propose that those accused but not convicted of a war crime should be extradited to the countries on whose territory the crimes had occurred. The political situation had changed drastically by the late 1920s, and the courts would no longer act on considerations of this nature. Consequently, the death of 234 people remained unatoned.

The War Criminal of the First, now in the Second World War

Helmut Patzig joined the NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers’ Party – the Nazi Party) 1 November 1933 62 , shortly after the party had come to power. Although he still went by the name of Brümmer, he wished to change his name again, as he now no longer feared extradition to the Allies. He was engaged in commerce in Riga and, in 1937, was appointed training manager of the local NSDAP-branch of his hometown. 63

Soon afterward, Patzig applied to the Reich and Prussian Ministry of the Interior to have his name changed. He informed resident officials in writing that, previously, he was obliged to change his name to Brümmer. Now, “after his return to the Reich and his redeployment in the navy,” his wish was “to be able to bear the name, at least in an ancillary fashion, under which he had become known during the World War.” The Navy High Command had given its endorsement to a corresponding application to the police commissioner in Berlin. 64 This action suggests that he had acquired a second home in the German capital.

According to his statement, after the National Socialist assumption of power, Patzig had moved to Zoppot, to Baederweg 1. As a resident of Berlin, he was reactivated by the German Navy as Lieutenant-Commander of the Kriegsmarine and promoted to Commander (Korvettenkapitän) on 1 December 1939. It was, therefore, no problem for Patzig’s name change to be authorized. As evidenced by the records, that he was a “party comrade and an active officer” proved to be advantageous to him. 65]

The Nazis were appreciative of Patzig’s attitude during the First World War and the Leipzig trials and knew how to utilize his naval expertise. From February to June 1940, he served in the German Navy in various submarine staff positions, in the French port of Lorient, for instance (June to September 1940), and in Königsberg (September to October 1940). From 28 January to 15 October 1941, he was the commander of a captured Dutch submarine, UD-4. He was primarily involved in training and was decorated with numerous military awards, such as the “Spange zum Eisernen Kreuz 2. Klasse” (Clasp of the Iron Cross 2nd class) and, in 1943, the “Kriegsverdienstkreuz II. Klasse mit Schwertern” (War Cross of Merit 2nd class with Swords).

After being deployed as firing instructor of the 25th U-flotilla (November 1941 to March 1943), Brümmer-Patzig was put in charge of the 26th submarine flotilla – established in April 1941 – from April 1943 to 9 April 1945. This flotilla served as a training unit and was based in Pillau until 1945, and then, for a short period, in Warnemünde, a small harbor town on the Baltic Sea. His promotion to Fregattenkapitän came on 1 February 1944. 66 After the war, Brümmer-Patzig returned to his occupation in commerce. He was by now in a second marriage. After the Federal Republic of Germany had been established, and when the opportunity arose, he applied for compensation for the material losses he had suffered in Zoppot. He died on 11 March 1984. 67

While he was head of the flotilla in the German Navy during the Second World War, Helmut Brümmer-Patzig encountered memories of his war crime during the First World War. His former helmsman, who knew more than he probably would have liked about him and his crime that had attracted worldwide attention in earlier days, paid him an unexpected visit. The former helmsman “asked” a favor for his son, who was doing service with the Navy on the Black Sea. He asked Brümmer-Patzig to take him into his division, if possible. Was it gratitude or even fear he felt for a witness who, had he testified, could have become very dangerous to him? Or was it a matter of genuine comradely empathy that induced Brümmer-Patzig to respond to the request of his former helmsman and to bring his son to Pillau and into his division? There the cadre seaman could survive the war years in relative safety, serving on an auxiliary cruiser.

Towards the end of the Second World War, the seaman received a confidential order from his commander. Brümmer-Patzig’s superiors should have been informed of the order but were not made aware. In the spring of 1945, with the war quickly drawing to a close, Brümmer-Patzig instructed two seamen from his division to take his private sailing yacht to a place of safety, ahead of the Red Army advancing from the east. The two seamen received explicit orders from Brümmer-Patzig not to take on board any of the civilian refugees who were fleeing East Prussia by the tens of thousands, hoping to be rescued by sea. The two seamen entrusted with carrying out this inexcusable and illegal order had to stand by and watch as women, children, and the elderly who were crowding at the harbor basin, flung themselves into the water, hoping to be rescued by the yacht. The helpless sailors could only watch. They could not do anything to assist the refugees on the exact order of Brümmer-Patzig, for whom the intactness of his private yacht was worth more than the lives of some German women, the elderly, and children.

Brümmer-Patzig’s order, under no circumstances, had anything to do with military necessity. Other German naval vessels, including U-boats, especially from Danzig/Gdansk and heading westward, took hundreds of refugees on board against official orders. For many years afterward, the son of the helmsman from U-86 felt tormented by the traumatic memories of not being in a position to rescue civilians who needed his help. He would share these memories with his father, albeit in a different context. Both father and son had become victims of the commander, who had been their superior in the two World Wars.

Years later, Brümmer-Patzig, living and working in North Rhine-Westphalia as a commercial employee, expressed gratitude towards his former helmsman for his silence. Brümmer-Patzig sent him half a pound of coffee twice a year, across the border into the eastern part of Germany. Then, about three decades later, by way of reciprocation for his gifts, he requested his former subordinate “colleague” in the Pillau division to supply him with a written declaration, stating that “the Russians” had “stolen” his private yacht. He presumably did this to be able to argue for compensation in a lawsuit. Because he never received any written statement from the son of his First World War shipmate, he was subsequently unable to include the yacht with his list of other material losses. Among the items for which he claimed compensation and provided documentary evidence, were things such as household goods, losses in savings, and the loss of a single-family house in Zoppot in which he had half ownership. 68

With a declaration from his erstwhile subordinate in his pocket, he would presumably have attempted to apply for financial compensation, even if the relevant provisions of the Equalisation of Burden Act of 1962 would probably not have authorized monetary payment for the yacht.

<With the request for a written confirmation attesting to the loss of the yacht, the memories of the events that occurred on the quay of the Pillau harbor came flooding back, which led to the father and son losing all previous feelings of gratitude towards their former commander. 69

(Return to December 2020 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

- I thank Professor Holger Herwig for his valuable help in writing this article. ↩

- Jörg-M. Hormann, “Erst verkannt und dann gefürchtet. Deutsche U-Boote im Ersten Weltkrieg 1914 – 1918,“ in: Schiff Classic: Magazin für Schifffahrts- und Marinegeschichte, no. 2, Munich 2014, 12 – 21. ↩

- For instance Ulf Kaack, Tödliche Begegnungen, Schiff Classic: Magazine 2014, 23 – 25. ↩

- John Horne and Alan Kramer, German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial (New Haven, Connecticut: 2001), especially 327 and 419. ↩

- A first attempt at a reappraisal of this maritime war crime can be found in the popular science article by Ulrich van der Heyden, “HMHS Llandovery Castle. Ein ungesühntes Kriegsverbrechen 1918“, in Militärgeschichte. Zeitschrift für historische Bildung, no. 2, Potsdam 2016, 22 – 23. ↩

- A document of the German Reich Interior Ministry states in this regard: “In order to evade being seized by the Entente, which had demanded his extradition, he fled in 1920 under the name of Brümmer.” – [„Um sich dem Zugriff der Entente zu entziehen, die seine Auslieferung gefordert hatte, flüchtete er im Jahre 1920 unter dem Namen Brümmer.“ – Federal Archives Berlin-Lichterfelde: BA, R 1501/127628: Namensänderung Patzig, sheet 208. ↩

- Günter Krause, U-Boot und U-Jagd, 2nd ed., (East Berlin: 1986), 32. ↩

- In this regard, the two most up-to-date, well-researched accounts (in German) are in Willi Jasper, Lusitania. Kulturgeschichte einer Katastrophe (Berlin: 2015); Erik Larson, Der Untergang der Lusitania. Die größte Schiffstragödie des Ersten Weltkriegs (Hamburg: 2015). On the anti-German response elicited by the sinking of the Lusitania, even in South Africa, see. Tilman Dedering, “Avenge the Lusitania: The Anti-German Riots in South Africa in 1915,” in Immigrants & Minorities. Historical Studies in Ethnicity, Migration and Diaspora, no. 3, (London: 2013), 256 – 288. ↩

- Wolfgang Krüger and Bodo Herzog, Der Entschluss zum uneingeschränkten U-Bootkrieg im Jahre 1917 und seine völkerrechtliche Rechtfertigung (Berlin/Frankfurt am Main: 1959). ↩

- Richard Lakowski, U-Boote. Zur Geschichte einer Waffengattung der Seestreitkräfte (East Berlin: 1985), 116. ↩

- Lakowski, U-Boote, 121. ↩

- Designation for non-series U-boats without numbering. ↩

- Lutz Unterseher, Der Erste Weltkrieg. Trauma des 20. Jahrhunderts (Heidelberg: 2014), 86. ↩

- Bodo Herzog, Deutsche U-Boote 1906–1966 (Erlangen: 1993), 123. ↩

- Herzog, Deutsch U-Boote, 68. ↩

- Friedrich Karl Kaul, “Völkerrecht ist außer Kraft gesetzt. Der Fall Boldt/Dithmar 1918–1928“, in Friedrich Karl Kaul, So wahr mir Gott helfe. Pitaval der Kaiserzeit (East Berlin: 1970), 296. ↩

- Kaul, “Völkerrecht,“ 296. ↩

- A well-researched depiction of this criminal act can be found in Harald Wiggenhorn, “Eine Schuld fast ohne Sühne”, in Zeit online, Dossier, 16.08.1996. This article is based on the book by Harald Wiggenhorn: Verliererjustiz: Die Leipziger Kriegsverbrecherprozesse nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg (Baden-Baden: 2005). ↩

- Herzog, Deutsche U-Boote, 309. ↩

- Kaul, “Völkerrecht,“ 301. – “Ein nach den Vorschriften des 10. Haager Abkommens gekennzeichnetes Lazarettschiff war torpediert worden! Seine Schiffbrüchigen hatte man in offenen Rettungsbooten beschossen und bis auf vierundzwanzig getötet! Das war eine Häufung von Völkerrechtsbrüchen, wie sie sich die kaiserlich-deutsche Marine bislang noch nicht zu leisten gewagt hatte.” ↩

- Federal Archive Berlin-Lichterfelde: R 9361 II (Collection Berlin Document Centre), shelf number: 121765, sheet 1524. ↩

- Files of the Reich Chancellery. Weimarer Republik, Vol. 1, cabinet meeting dated 22 July 1921, 148 (online edition). – “…daß im Falle der Richtigkeit der Meldung alles getan werden müsse, um die Auslieferung zu erreichen.“ ↩

- Files of Reich Chancellery 150. – “Die Reichsregierung teilt die Anschauungen, daß die einseitige Aburteilung deutscher Kriegsverbrecher unsittlich ist und von dem Volksempfinden mit Recht als eine brutale Vergewaltigung jedes Rechtsgefühls empfunden wird. Sie ist deshalb gewillt, sobald hierzu der geeignete Zeitpunkt sich darbietet, den Anspruch auf gleichmäßige Behandlung der fremden Kriegsverbrecher zu erheben und hierfür die Gegenliste als Grundlage zu benutzen. In diesem Augenblick aber scheint ihr dieser Zeitpunkt nicht gekommen zu sein.” ↩

- Gerd Hankel, Die Leipziger Prozesse: Deutsche Kriegsverbrechen und ihre strafrechtliche Verfolgung nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg (Hamburg: 2003). ↩

- Frank Neubacher, Kriminologische Grundlagen einer internationalen Strafgerichtsbarkeit. Politische Ideen- und Dogmengeschichte, kriminalwissenschaftliche Legitimation, strafrechtliche Perspektiven (Tübingen: 2005), 310. ↩

- Walter Schwengler, Völkerrecht, Versailler Vertrag und Aus (Stuttgart: 1982), 348. ↩

- Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office: Rechtsabteilung, R IV: Kriegsbeschuldigte, Brief des Oberreichsanwalts an das Auswärtige Amt, 23.02.1921. ↩

- Kaul,“Völkerrecht,“ 305. – “Ihren guten Willen an dem Exempel eines der Prominentesten zu statuieren war nicht möglich und lag nicht in ihrem (der Reichsregierung – UvdH) Interesse. So kam man im Reichsjustizministerium, dem zu dieser Zeit der Sozialdemokrat Radbruck vorstand, mit den Herren der roten Roben überein, den Fall der beiden in der Öffentlichkeit unbekannten Marineoffiziere als ‚Muster’ zu benutzen. Außerdem konnte der gegen sie erhobene strafrechtliche Vorwurf… in der Geschichte des Seekrieges wirklich seinesgleichen suchen.” ↩

- Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office, R IV: Kriegsbeschuldigte Nr. 2, Verhaftung und Auslieferung des Oblt. Dithmer. ↩

- Schwengler, Völkerrecht, Versailler, 348. ↩

- Mention is made in a letter to the Reich Minister of Justice to the Foreign Office, dated 18 May 1921, of a “meanwhile allegedly deceased Chief Petty Officer Second Class Meissner”. Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office, R IV: Auswärtiges Amt, Friedensabteilung. ↩

- Kaul, “Völkerrecht,” 308. One of the four seamen who operated and were close to the cannon had apparently injured his hand during firing. One of the other three took over. ↩

- Hankel, Die Leipziger Prozesse, 457. ↩

- Hankel, Die Leipziger Prozesse, 458. ↩

- Schwengler, “Völkerrecht,” 148. Quoted from the bill of indictment – “ganz abgesehen davon, daß sie durch ihr Ausschauen einer Gefährdung des U-Boots von anderer Seite vorgebeugt und dadurch überhaupt erst für Patzig die Möglichkeit zu seinem Vorgehen gegen die Boote geschaffen.” ↩

- These questions arise not only from the author of this essay, whose grandfather was the witness of the crime. The personal representations are based on many conversations with the grandfather. ↩

- Neubacher, Kriminologische Grundlagen, 311. ↩

- Andreas Michelsen, Das Urteil im Leipziger Uboots-Prozeß ein Fehlspruch? Juristische und militärische Gutachten (Berlin: 1922). ↩

- Quoted in Michelson, Das Urteil, 56. ↩

- Neubacher, Kriminologische Grundlagen, 312. ↩

- Heiko Ahlbrecht, Geschichte der völkerrechtlichen Strafgerichtsbarkeit im 20. Jahrhundert. Unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der völkerrechtlichen Straftatbestände und der Bemühungen um einen Ständigen Internationalen Strafgerichtshof (Baden-Baden: 1999), 45. ↩

- Hankel, Die Leipziger Prozesse, 463. ↩

- Constanze Schulte, Compliance with Decisions in the International Court of Justice (Oxford: 2004). ↩

- Dirk von Selle, “Prolog zu Nürnberg. Die Leipziger Kriegsverbrecherprozesse vor dem Reichsgericht,“ in: Zeitschrift für Neuere Rechtsgeschichte, no. 3/4, Vienna 1997, 192 – 209; James F. Willis, Prologue to Nuremberg: The Punishment of War Criminals of the First World War (Westport: 1982). ↩

- Wiggenhorn, Verliererjustiz, “Eine Schuld fast ohne Sühne,“ “Es ging so einigs nicht ganz rechtsstaatlich zu, damals in Leipzig.” ↩

- Hankel, Die Leipziger Prozesse, 500. ↩

- A detailed description of the escapes is provided in Kaul, “Völkerrecht,” 310 – 316. ↩

- Claud Mullins, The Leipzig Trials: An account of the war criminals’ trials and a study of German mentality (London: 1921), 108 and 134. ↩

- Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts), R 48433: Letter of the chief Reich prosecutor to the Reich Minister of Justice (with enclosures), 13.03.1928, (transcript) sheet 189. ↩

- Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office, R 48433: Report of the Foreign Office, dated 12.04.1928, sheets 163–164. ↩

- Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office, R 48433: Letter from the Foreign Office to the Reich Minister of Justice, 26.07.1926 (transcript), sheets 104–107. – “die einschlummernde Kriegsgreulpropaganda im Auslande zu neuem Leben erwecken…” ↩

- Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office, R 48433: R IV: Letter from the chief Reich prosecutor to the Foreign Office, 20.07.1926, sheet 100. ↩

- Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office, R 48433: Sachdarstellung, im Ausland, d. 6. Mai 1926 (transcript), sheets 116–127. ↩

- Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office, R 48433: sheet 118. ↩

- Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office, R 48433: Erklärung…, sheet 150. – „… mit Soldaten gefüllt, die sich wieder in die feindlichen Reihen einstellen würden.” ↩

- Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office, R 48433: Sachdarstellung…, sheet 126. – “Heute bin ich der Ansicht, daß ich in ähnliche Konflikte gestellt, auch wieder ähnlich handeln müßte.” ↩

- The chapter summarising the countervailing facts: “Die heimliche Wiederaufnahme des Falles, ‘Llandovery Castle’ von 1922–1931“, in: Katrin Hassel, Kriegsverbrechen vor Gericht. Die Kriegsverbrecherprozesse vor Militärgerichten in der britischen Besatzungszone unter dem Royal Warrant vom 18. Juni 1945 (1945–1949), (Baden-Baden: 2008), 63 – 67. ↩

- Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office, R 48433: Erklärung, sheet 150f. ↩

- Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office, R 48433: Sachdarstellung…, sheet 124. – “Es hatte keinen Zweck, sich über das Geschehene zu zergrübeln.” ↩

- Schwengler, Völkerrecht, Versailler, 358. ↩

- Hankel, Die Leipziger Prozesse, 503f. ↩

- Federal Archive: R 9361 II (Collection Berlin Document Centre), shelf no.: 121765, sheet 1524. ↩

- Federal Archive: R 9361 II. ↩

- Federal Archive Berlin-Lichterfelde: R 1501/127628, sheet 206–210. ↩

- Federal Archive Berlin-Lichterfelde: In an administrative note, it states: “In 1931 he obtained permission in Danzig/Gdansk to use this name (Brümmer – UvdH). Since there no longer exist any grounds under current circumstances for him to conceal his name, Patzig, he requests that he may be called by this name again and, to wit, as an additional name to the one he currently holds. He will not relinquish the name Brümmer again, as he has, for the last nineteen years, been known under this name to an entire circle of individuals. He has furthermore gone through very difficult times under this name.” – “In view of the services rendered” by the applicant, councillor Lettner, who was dealing with the process, proposed a positive, free-of-charge outcome for the application, which subsequently happened. – [”Im Jahre 1931 hat er in Danzig die Genehmigung zur Führung dieses Namens erhalten. Da unter den heutigen Verhältnissen kein Grund mehr vorliegt, seinen Namen Patzig zu verschweigen, bittet er, ihn nunmehr wieder tragen zu dürfen, und zwar als Zusatzname zu seinem gegenwärtigen Namen. Den Namen Brümmer wird er nicht wieder ablegen, da er 19 Jahre lang unter diesem Namen einem ganzen Kreise von Menschen bekannt geworden sei. Ferner hatte er unter diesem Namen die allerschwersten Zeiten bestanden.“ ↩

- Hans-Joachim Busch, Rainer/Röll, Der U-Boot-Krieg 1939–1945: Die deutschen U-Boot-Kommandanten (Hamburg/Berlin/Bonn: 1996), 39. ↩

- Kulturlexikon Langenberger. Immaterielles Kulturerbe der UNESCO, www.unter-der-muren.de/kulturlexikon.pdf, 919. ↩

- Federal Archive: Equalisation of Burden Authorities – “Brümmer-Patzig, Helmut”, shelf no.: ZLA 1/13395872. ↩

- An upcoming book will deal with the subject in more detail: Ulrich van der Heyden, Helmut Patzig – U-Boot-Heroe oder Verbrecher?( Solivagus Verlag: Kiel, 2021). ↩