John Rodgaard1

Captain, USN (Ret.)

Words such as admiration, contempt, cooperation, and hostility might describe the Anglo-American naval relationship that followed The Napoleonic Wars. Yet, that relationship formed the framework for today’s Anglo-American naval partnership. Examining the Anglo-American naval relationship between 1815 and 1837, we begin with the culture and values that both navies shared.

On 27 March 1794, the US Congress authorized the construction of six frigates under the War Department. On 30 April 1798, Congress established the US Navy (Although, the US Navy officially recognizes 13 October 1775 as the birth of the US Navy). In July, the Department of the Navy formally established the Marine Corps, and the first six frigates mandated by Congress were completed and commissioned. 2 Now the nation needed an officer corps and seamen to man the Navy’s ships. With recommendations from President John Adams and Captains John Barry, Samuel Nicholson, Thomas Truxton and Richard Dale, the Secretary of War, James McHenry, selected “… six captains, 15 lieutenants and 21 midshipmen, three sailing masters, four surgeons, five surgeon’s mates, and five pursers…” to form the Navy’s first naval officer corps. Enlisted personnel were recruited through a two-year volunteer enlistment contract – impressment was forbidden.

Dr. Christopher McKee asked how the US Navy had so quickly developed into a “… highly professional naval force … in eighteen years?’ Of the five elements that composed a navy (ships, shore establishments, civilian administration, seamen, and officers), the critical element was the US Navy’s officer corps.

The newly-formed navy chose, as its model, the Royal Navy. McKee wrote, “…the choice was predetermined. The navy of Great Britain was part and parcel of the American colonial heritage.” In addition, Benjamin Stoddert, the first Secretary of the Navy said, “We must imitate [the British] in things which tend to the good of the services.” In 1804, Lieutenant Arthur Sinclair, USN observed that “… the customs of the British sea services, in cases not embraced by our laws, have usually been the criterion by which we have been guided.” McKee wrote: “The historian is struck by the speed with which the transfer was accomplished, by the early date at which the fledgling navy of the Quasi-War and the Tripolitan War required the professional polish and established methods characteristic of a far more mature organization.” Surely such maturation was due to the manner in which the US Navy adopted Royal Navy operations.

Within the officer corps, the captains had combat-at-sea experience and the lieutenants were masters of sailing technology. All knew sail, ships, and the sea. Additionally, American naval officers expanded their professional development in the naval arts through self-education. McKee observed, “American naval officers owned, borrowed, read, and internalized the professional British naval literature – The Naval Chronicle and A System of Naval Tactics …” of the period. While at sea, they also had opportunities to observe the Royal Navy, especially at its operational nexus – Gibraltar. Beginning in 1800, American naval squadrons, ordered to the Mediterranean to fight the Barbary States, chose Gibraltar as a major communication and supply base. American and British officers continued to rub elbows at Gibraltar through the mid-nineteenth century.

McKee gave another example of how Royal Navy culture was transferred to the US Navy. It was through those sailors who volunteered to serve. Midshipman John Roche, Jr., USN, wrote to his father in 1798, while aboard the US Frigate Constitution, saying, “Our petty officers are very good men. Most of them, such as quartermasters, master’s mates, gunners, master-at-arms, etc., are either English or Irish who have sustained the same berths on board British men-of-war.” Thus, the lower deck could have fitted into either navy without much difficulty. Dr. Usher Parsons observed that, like the crews of British warships ‘… the crews of US warships were perceived by their officers as ‘a rough and rugged class of men,’ accustomed to and requiring severe physical punishment for their management.” The US Navy continued the “long tradition of naval justice inherited from the British role model; the pedagogical and conservative roles of tradition were not to be ignored. As aboard ships of the Royal Navy, the ‘rough and rugged class of men’ manning US warships experienced instant justice.” Minimum infractions were punished with men being denied their grog or being clapped in irons with reduced rations and no grog. Then there was flogging. Although the death penalty was on the books, it was the extreme exception even when an offence stipulated such in the regulations.

Concerning regulations, the US Naval Regulations of 1802 and the corresponding US Marine Corps Rules of 1798 relied heavily on the Regulations & Instructions Relating to His Majesty’s Service at Sea. However, as McKee wrote: “It would be wrong to think of either set as simply the product of a copy to the British Regulations and Instructions, scissors, paste, and a printing press.” 3 Yes, senior US Navy officers did assemble the new regulations by borrowing and excluding those from the British example as they saw fit. But, they also incorporated their own, and compiled them within the guidelines of US Constitution and Federal Statutes.

The men selected for the first US Navy officer corps became known as Barry’s Boys; named for Commodore John Barry. These officers piloted the Navy’s course for the next sixty years. Names such as Bainbridge, Barren, Decatur, Porter, Somers, and Stewart placed the US Navy on a solid foundation. But, domestic politics held considerable sway. As Professor John Hattendorf wrote in an article for the Naval War College:

Americans were having a serious debate as to the “purpose and function of the navy”. There were two political camps: One, the Federalists who believed ‘the new navy should be the most effective expression and symbol of the nation’s power, honor, and prestige as well as a potent and capable and effective fighting force that played a major role in the world balance of power as an instrument of political influence.” 4

A second influential group were the Republicans; the anti-navalists. While they recognized a need for a navy, they argued that Federalists aims were unrealistic and too costly. They visualized a small, militia-type navy, consisting mostly of gunboats for coastal protection, with a few large ships operating on distant stations – just enough to protect American commerce. Except for the Navy’s expansion during the War of 1812 and the American Civil War, the Republican vision held sway through most of the nineteenth century. According to Professor Hattendorf, the Republicans believed:

British maritime superiority was a political and naval fact … Freed from this burden, the US Navy could concentrate on a more select range of tasks. What it could and did do was bounded, by both its capabilities and interests, as well as the political compromises necessary in the creation of practical naval policy and strategy. 5

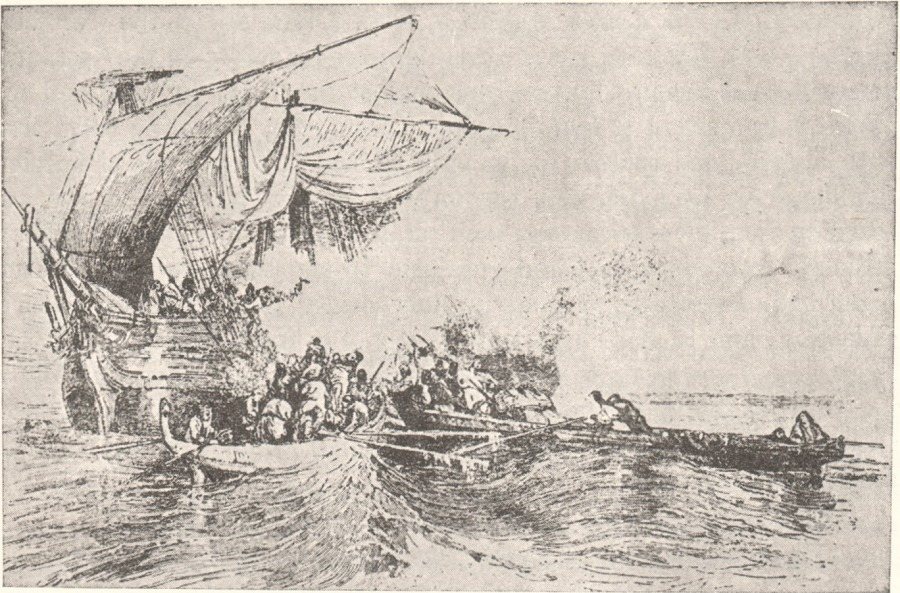

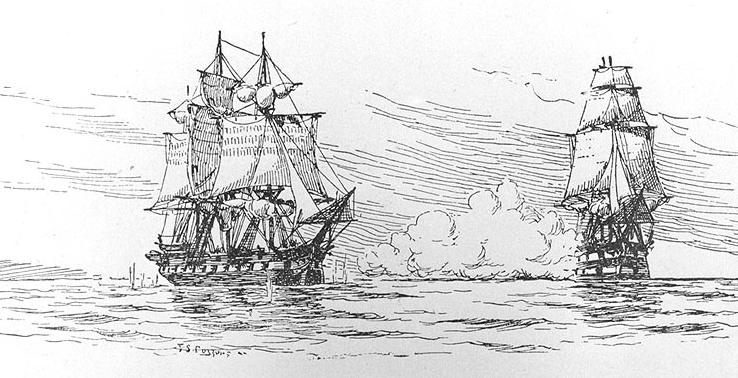

The incident between HMS “Leopard” and USS “Chesapeake” that sparked the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair. Drawn by Fred S. Cozzens and published in 1897. (Wikimedia Commons)

The US Navy concentrated on supporting and defending American maritime activities. The remainder of this article will discuss Anglo-American naval competition and cooperation through officer interactions and visits, defending trade in the Mediterranean, anti-slavery patrols in the Caribbean, and maritime scientific advancements during the early nineteenth century.

A Visit to America

After 1815, the relationship between the two navies reflected a mutually subdued appreciation for the qualities and limitations of each. One example can be seen through the eyes of a twenty-two-year-old Royal Navy officer who arranged leave from his duties at the Royal Navy’s North American Station in Halifax, Nova Scotia to visit the United States. In a book published in 1827, 6 Lieutenant F. Fitzgerald De Roos wrote about his one-month-long whirlwind tour. His insights on America, especially its navy, revealed aspects of life in the early republic. He was keen to see how Americans built their exceptional warships, famous for impressive exploits during the War of 1812.

In the company of Major Yorke, he sailed to New York City, bound for Washington, DC. From New York, he travelled by steamboat and horse-drawn coaches to Philadelphia, which, De Roos wrote, “Has the appearance of a well-built old English town of the time of Queen Anne.” Staying just long enough to drop off correspondence to the British consulate, the two officers travelled to Baltimore and Washington, DC. Reaching Washington, he delivered dispatches to the British minister, Mr. Vaughan, who escorted De Roos and Yorke to the Capitol. De Roos was “struck by its immense size … the senate-room and the chamber of representatives … remind me strongly of the Chamber of Deputies at Paris.” Vaughn then took De Roos and Yorke to the Washington Navy Yard. De Roos was surprised by the Marine guard’s the lack of interest in foreign visitors. The Marine said that, “he guessed we were at liberty to see any part of it we pleased.”

Walking through the yard, De Roos saw three frigates in various stages of construction or repair. The one that he identified as the Susquehanna was on the building way:

She was constructed on the latest and most approved principles of the American builders, and was to mount 60 guns. Her timbers were close together, and her shape remarkable for a very full bow, and a perfectly straight side. She had a round stern, but its rake and flatness, combined with judicious construction of her quarter galleries, gave it quite the appearance of being square. 7

Describing the second ship, the US Frigate Potomac (44), he wrote that she was “… another heavy and clumsy-looking 60 gun frigate, was hauled up on ways … called Commodore Porter’s inclined plane.” The third frigate, the USS Congress (38), was newly overhauled, and he was allowed to go aboard. 8 As the three left the yard, they came across a monument:

… which was erected to the memory of some officers, and bore an inscription declaring it to have been mutilated by Britons at the taking of Washington. At the capture of this city, many excesses were undoubtedly committed, but I have been assured that there are no grounds for this particular accusation. Let it, however in justice be observed, that this is the only public inscription of memorial which I saw in the United States, of a nature calculated to wound the feelings of a stranger. 9

The monument was the oldest naval monument in the United States. It honoured those US naval officers who were killed during the Barbary Wars. 10 After spending an enjoyable evening in “…George’s Town, which had all the agreeable characteristics of a European assembly,” Roos and Yorke were invited to attend the only Episcopal church in the city. Present at the service were President Monroe and the recently returned ambassador to the Court of Saint James, Richard Rush. 11 One wonders if the preacher’s sermon was targeted at the two British officers:

The sermon was worthy of the preacher; it treated of the oppression which the United States formerly endured while under the yoke of England, whose downfall, discomfiture, and damnation he confidently predicted … I strongly suspect that the blasphemous absurdity was the produce of his own brain. I was sorry to learn that this man was considered much superior to American preachers in general.

Following the church service, De Roos was invited to a Virginia household, where: “Politics and travelling form the usual topics of conversation … The events of the last war, and the capture of Washington in particular, I found to be a frequent topic.” De Roos compared the American experience of the war with his own and that of Europe in general when he wrote: “The attention of Europe was so completely engrossed by the mighty conflict, which decided its fate on the plains of Waterloo, that the Washington campaign was regarded with comparative indifference.”

Travelling back to New York De Roos stopped at Baltimore, “… a port justly celebrated for its shipbuilding.” Walking down to the shipyards he noted, “… I saw a schooner building … Everything was sacrificed to swiftness, and I think she was the most lovely vessel I ever saw.” A shipbuilder showed him a book containing architectural ship drawings; “… drafts of all the fastest-sailing schooners built in Baltimore, which had so much puzzled our cruisers during the war. It was everything I wanted; but after an hour spent … I could not induce him to part with one leaf of the precious volume.” De Roos wrote: “I could not help admiring the public spirit which dictated his conduct, for the offer I made him must have been tempting to a person in his station of life.” So much for De Roos’ attempt at gathering intelligence!

Arriving in Philadelphia, he called upon the British consul, who took him to the birth place of the US Navy; the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Upon arriving, he saw on stocks the incomplete hull of the first-rate, USS Pennsylvania (136), the largest sailing warship ever built by the United States. He wrote: “A mistaken notion has gone abroad as to the Americans calling such ships … seventy fours [third rate], which, at first sight, …bears the appearance of intentional deception.” However, he knew that Congress had authorized the building of only third rate ships-of-the-line, but the Navy Commissioners took the liberty to build Pennsylvania and others “on a more extended scale.”

On his return to New York, De Roos visited the Brooklyn Navy Yard and was struck by the level of activity as well as the warships he observed. The yard was building the US Frigate Brandywine (60) and fitting out the sloop-of-war, USS Boston (20). Aboard the Boston, he noted an ingenious improvement:

To avoid the weakness … which is always made in the after-part of the lower-decks of vessels of this description, in order to give greater accommodation to the officers, it was laid so as to form a plane inclining toward the stern, and by this method, strength was united with convenience. So roomy was her hold, that there was sufficient space to pass between them and the lower-deck. By this means, she was enabled to dispense with hatches.

He next went aboard the first-rate USS Ohio (102), which was lying in ordinary. “A more splendid ship I never beheld.” However, he “… was filled with astonishment at the negligence which permitted so fine a ship to remain exposed to the ruinous assaults of so deleterious a climate … and … is already falling rapidly into decay.” De Roos later found that as with other American warships, the Ohio:

… was an instance of the cunning, I will not call it wisdom, which frequently actuates the policy of the Americans. They fit out one of the finest specimens of their shipbuilding in a most complete and expensive style, commanded by their best officers, and manned with a war-complement of their choicest seamen. She proceeds to cruise in the Mediterranean, where she falls in with the fleets of European powers, exhibits before them her magnificent equipment, deploys her various perfections, and leaves them impressed with exaggerated notions of the maritime powers of the country which sent her forth.

De Roos travelled next to Boston’s Charlestown Navy Yard, where he was impressed with its size and the large ship storage houses. At the yard he was told that the:

… Americans propose to divide their ships into five classes, namely, three-deckers, two-deckers of 102 guns, frigates of 60 guns, corvettes of 22 guns, and schooners. On the model of every ship a committee is held – the draft determined on, and transmitted to the builders of the dockyards; and as periodical inspections take place, no deviation from the original model can occur. This system of classification and admirable adherence to approved models has been attended by the most beneficial results, which are visible in the beauty and excellent qualities of the ships of the United States.

Ending his tour, De Roos reflected upon his experience: “Everything in America is upon a gigantic scale. How enormous are its resources! How boundless its extent! … From the energies she has displayed in her infancy, to what powers may not her maturity aspire?” However, his observations about the future of the US Navy were less than prophetic:

My humble lucubrations were directed, during my tour, to points more immediately connected with my own profession; and I took my leave of America, with the satisfactory conviction that the naval strength of the United States has been greatly exaggerated – that they have neither the power nor the inclination to cope with Great Britain in maritime warfare – far less to presume to dispute with her the Dominion of the Seas.

The Mediterranean

With the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the US Navy re-entered the Mediterranean. We can see aspects of the relationship between the two former enemies through the eyes of two men who left their respective journals to future historians. George Jones wrote his journal while in the Mediterranean Squadron between 1825 and 1827. 12 Although Francis Schroeder wrote his journal just after the end of the Georgian Era (1843 and 1845), his observations remain relevant. 13 Besides writing about their experiences with the squadron, both men provided insights into the Anglo-American relationship as a whole.

In 1825, Jones joined the US Frigate Brandywine (54) as a schoolmaster to the ship’s midshipmen. Brandywine, the second-rate USS North Carolina (90), and the sixth-rate sloop-of-war USS Erie (20) comprised the Mediterranean Squadron. Before entering the Mediterranean, Brandywine’s crew had the honor of returning the Marquis de Lafayette to France after the hero’s grand tour of the US. The trip was so arduous that the frigate required emergency repairs. Instead of re-caulking the ship’s hull in France, Brandywine’s captain sailed across the Channel to Portsmouth. Jones wrote that he was shocked by this decision, as it was only seven years since the war. “I should have thought him [the captain] foolishly jesting or mad.”

However, Jones’ shock turned into admiration during Brandywine’s stay. He described the port and naval dockyard as a “… beautiful sight … a noble enemy to cope with …” 14 He visited HMS Victory and sailed to the Isle of Wight. He was impressed by the Royal Navy and the beauty of the island. He also wrote, “Our ship has had a great many visitor, and I understand has been greatly admired.” 14

A similar experience occurred to then Midshipman Charles Wilkes, USN. In his autobiography, Rear Admiral Wilkes wrote about his visit to the heart of British sea power in 1818. “At Cowes the ship was much frequented by officers & men who seemed desirous of gratifying their curiosity by inspecting the American frigate who had celebrated the naval victories over them. The Guerriere …was equipped well for a fighting one and as such did credit to our country.” 16 However, his opinion of the Royal Navy Base at Portsmouth was in marked contrast to that of Jones who visited seven years later:

I was much [struck] at the want of system in the English dockyard and the want of arrangement. The wooden walls of Old England did not impress me with much respect. The Victory & other ships of note were laid up dismantled and, of course, it is difficult to impress one with much veneration for a small, dismantled hull. The Victory was of small dimension in our eyes, and the impression was how inferior to that of our own ship, both in size and armament…showing the progress that naval architecture and efficiency for combat had made within the last 20 years. 17

Jones visited Gibraltar on 2 November 1825. Walking about, he was especially taken by one regiment – The Black Watch. He wrote that they “… are conspicuous, the brave ‘forty twa’s’ in their fantastic highland dress. They are fine looking fellows, with muscular limbs, stout frames and national features.” 18

Six months later, the American squadron returned to Gibraltar to pick up spring dispatches from the Navy Department and State Department. The squadron arrived on King William IV’s birthday (17 April 1826). Jones observed that the “Rock” was celebrating in grand style. In full dress, the regiments of the garrison fired volleys and marched in review past the governor. “Nowhere, probably, can troops be found, in better order: their precision in exercise is astonishing to one accustomed to the militia parades. The Scots were there with their bagpipes and drew particular attention.” 19 He also noted that all the ships in the bay and harbor dressed ship, with the ships of the American squadron flying the Union Flag from their foremasts.

Francis Schroeder, secretary to the American Squadron’s commodore, Captain Joseph Smith, aboard the flagship, the US Frigate Cumberland (50), expressed the same sentiment seventeen years later. “We received the salutes of sentinels at every turn … I should again exclaim in admiration of the English soldier.” 20 Schroeder and the squadron spent Christmas 1843 in Gibraltar. In a letter to a friend, he expressed his admiration for British engineers regarding the “… extent, and ingenuity and immense labour with which they have been contrived. I was filled with amazement.” 21

In June 1826, the American squadron entered the Aegean Sea, arriving at the island of Sifnos. The Greek War for Independence against the Ottoman Empire was raging. One aspect of the revolution was the scourge of Greek piracy. The squadron was escorting American merchant ships trading with the Ottomans as well as working with the Royal Navy squadron in anti-piracy operations. At Sifnos, the British flagship of the squadron, HM Frigate Cambrian, had arrived and the American commodore visited with his British counterpart. Jones wrote:

We meet the vessels of that nation frequently and I am much pleased to see harmony and good feeling subsisting between their officers and our own. Dinners and visits exchanged from Captains to Midshipmen; picnics are made for each other; and speaking the same language, with common objectives of esteem and antipathy, they appear much like officers of the same nation; and so it should be.

On 30 April 1827, the American squadron arrived at the port of Smyrna (Izmir, Turkey) to show the flag. Smyrna was the major trading port between the United States and the Ottoman Empire. In Jones’ writings, we see another instance of cordial Anglo-American naval relations: “We received the usual compliments on anchoring: visits have been frequent between the officers and ours: our midshipmen are giving a dinner to those of HM Frigate Seringapatum and the cries of ‘Hip, Hip, Hip – Huzza, etc.’ among them, are beginning to be thick and indistinct.”

Then again, arguments and slights did occur between the two navies. When the Constitution arrived at Piraeus, Greece, several British, French and Austrian warships were anchored there. HMS Cambrian and the Royal Navy flagship rendered honours to the arriving American. Jones wrote that as the Constitution passed by, Cambrian’s band played Hail Columbia. Constitution’s band responded with God Save the King. Then Cambrian played Yankee Doodle. Jones did not like the way the British ship played it. “They ‘rattled it off’ … I am sure it must have produced a general laugh there as it did with us. To me … it produced mortification.” 22

Combatting Slavers

After the defeat of Napoleonic France, both navies waged another kind of war – the war against the African slave trade. Over the next three decades, they opposed the slave trade off the coast of West Africa and throughout the Caribbean. Their shared mission was truly ironic in that the wealth from human trafficking had shaped the prosperity of both countries. However, each country approached the trade differently. The US had tried, since the inception of its federal government, to suppress slavery in the Caribbean. President John Adams’ administration passed the Act of 1794, prohibiting Americans from transporting people to another country for the purpose of selling them as slaves. Heavy financial penalties, to include the confiscation of vessels, were imposed on those found to be conducting such activities. While the law originally had no enforcement provisions, fines and possible imprisonment were added during the last year of Adams’ administration. Further, US Navy warships were authorized to seize US slavers operating in the Caribbean as prizes. However, along the American coastline:

… the enforcement of foreign trade regulations was the provenance of the Revenue Cutter Service of the Treasury Department … the Revenue Cutter Service and federal marshals … were active, though with varying rates of success, in suppressing the trade as it occurred on the American coast and in its harbors. 23

However, with the Jefferson administration in 1801, interdiction by the Revenue Cutter Service and by federal marshals at the source of interdiction (harbours and ports) dropped off precipitously. The Jefferson Administration’s anti-navalism severely reduced the size of the US Navy’s warships as well as the number of Revenue Service cutters. As a result, the percentage of American ships operating in the slave trade almost doubled. 24

The Louisiana Purchase fed the demand for slaves. This vast territory, together with the invention of the cotton gin and improved methods of cultivating and processing Louisiana sugar cane, required thousands of slaves. Although the absolute ban on importation of slaves commenced in 1808, the illicit importation of Africans continued, but at a reduced rate. However, the demand for slaves was increasingly satisfied by a:

… new class of American traders … supplied with home-grown captives born into slavery on Virginia and Maryland farms. The conditions were right for a massive forced migration of enslaved Chesapeake labourers down South, and it did not have to be a one-time drain: a continuing domestic slave-breeding industry was possible. 25

After the Napoleonic War, the US Navy became more active in law enforcement. With American-flagged ships conducting illegal slave trade, and the rise of piracy in the Gulf of Mexico and east Florida coast, the Navy assembled its first squadron to combat piracy and the slave trade. By the 1820s, the Navy had established the West Indies Squadron consisting of two frigates, a sloop-of-war, and five schooners. However, the squadron could seize only American slave ships. 26 It did not take long for American slavers to reflag their ships to evade the US Navy.

The US government sent a US Navy squadron to Africa’s west coast in 1819, under the command of Commodore Matthew C. Perry. But Perry’s squadron, and subsequent squadrons sent out for the next twenty years, did not have enough ships to patrol the vast African coastline and the slave routes across the Atlantic. In fact, the Navy did not have a consistent presence until 1842. As a result, the US Navy caught few slavers, compared to the Royal Navy’s West Africa Squadron. Britain abolished all aspects of the slave trade by British subjects in 1807, and that included seizing ships fitted out for slave transportation and not having slaves aboard. During the height of the Napoleonic War, the Royal Navy dispatched the first tactically-paired warships to Africa’s west coast. 27 Also, the Crown offered letters of marque to stimulate private ventures in seizing slavers. However, during the first decade of the law’s enforcement, the Royal Navy had to tread lightly so as not to confiscate slavers from those countries fighting Napoleon, such as Portugal.

With the end of the Napoleonic War, the Royal Navy’s West African Station established a naval station at Freetown, Sierra Leone in 1819. The first squadron consisted of just six ships, and it couldn’t possibly cover the entire expansive west coast of Africa ranging north of Sierra Leone down through the Gulf of Guinea toward modern day Nigeria. During the succeeding two decades, the squadron was enhanced to the point that it eventually comprised nearly 5 percent of Royal Navy commissioned warships. Additionally, Britain established special courts with judges from the various countries who signed the provisions of the Congress of Vienna. Throughout the remaining decades of the nineteenth century, British governments expanded the anti-slavery operations of the Royal Navy beyond the west coast of Africa, to include the Mediterranean, Red Sea, and Indian Ocean.

The Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842, with a provision to end the slave trade on the high seas, validated the US Navy’s contribution to the Africa Squadron. However, as Donald Canney’s book, Africa Squadron: The U.S. Navy and the Slave Trade, 1842-1861, states, the American squadron failed in its objectives. He wrote that, “… the squadron was unsuccessful, even though it was [ironically] the Navy’s only permanent squadron with a specific, congressionally mandated mission: to maintain a quasi-blockade on a foreign shore.” 28

Science and Exploration

The end of the Napoleonic Wars brought about an explosion in scientific and surveying endeavors by both navies. The United States oriented much of this exploration toward the country’s continental expansion, although significant oceanic accomplishments supported the expansion of overseas trade. In response to Britain’s rapid post-war global economic expansion, the Royal Navy improved navigational and time-keeping instruments and created new supporting scientific organizations.

Britain’s Hydrographer to the Admiralty and subsequent Admiralty’s Hydrographic Department was one such result. On the order of King George III, Alexander Dalrymple was appointed as the Hydrographer to the Admiralty in 1795. The King charged Dalrymple and the organization under his guidance to catalogue and centralize existing charts from private chart publishers and foreign sources. The first mass-produced Admiralty chart appeared in 1800, which supported the Royal Navy’s blockade of France’s Brittany coast. Subsequent charts were created and published to support naval operations in the Mediterranean, followed by charts of the North Sea and the English Channel. 29 Prior to his death in 1808, Dalrymple also produced sailing directions and notices to mariners’ journals. 30

Dalrymple’s successor was Captain Thomas Hurd, RN, who “… brought considerable surveying experience, having spent nine years making a detailed survey of Bermuda.” 31 He standardized hydrographic surveying methods, improved the efficiency of Admiralty mass-produced charts, and made production costs part of the Admiralty’s annual budget. Hurd also made Admiralty charts available to merchant mariners. In 1819, Hurd negotiated with the Royal Danish Navy what is believed to be the first bilateral agreement with a foreign government to exchange charts and supporting publications.

In 1823, Rear Admiral Sir W. Edward Parry, RN was appointed the third Hydrographer to the Admiralty. Parry, together with the Royal Society, organized scientific and surveying expeditions to the South Atlantic in cooperation with French and Spanish hydrographers. 32

Parry preceded Rear Admiral Sir Francis Beaufort who, in 1829, introduced a wind intensity scale named for himself –The Beaufort Scale – as well as a tide tables in 1833. He continued Parry’s program of scientific and surveying expeditions, of which the most famous were those conducted by Captain FitzRoy, commanding HMS Beagle. 33 The US Navy, as well as America’s merchant mariners purchased and benefitted from Admiralty charts. In 1830, the US Navy established the Depot of Charts and Instruments (the forerunner of the Navy’s Hydrographic Office). 34 In 1833, the thirty-five-year-old Lieutenant Charles Wilkes, USN took charge of the Depot of Charts and Instruments. During his naval service, he had shown considerable aptitude for coastal survey work along the American east and gulf coasts.

In 1836, The US Congress authorized the formation of a US Navy Exploration Squadron with Charles Wilkes in command. It was an interdisciplinary scientific expedition for “exploring and surveying the Southern Ocean.” 35 It departed in 1838. Lieutenant Matthew Fontaine Maury, USN, one of the US Navy’s prominent hydrographers and scientists, followed Wilkes. His formative experience took place between the time he received a midshipman’s warrant at age nineteen in 1825, and 1837, when he studied navigation, meteorology and the world’s oceans. He eventually became the superintendent of the US Naval Observatory and the head of the Depot of Charts and Instruments. He made major contributions to humankind’s understanding of the world’s oceans, its currents, and winds. Maury became known as the Father of Modern Oceanography. After the American Civil War, the United States Hydrographic Office was established under the Navy’s Bureau of Navigation. 35

Conclusion

Yes, words such as admiration, contempt, cooperation, hostility, respect and rivalry might describe the early Anglo-American naval relationship. This synopsis has shown that the relationship was indeed complicated. As the generation of men who fought against one another during the War of 1812 passed slowly from the scene, hostile attitudes gave way to cooperation (sometimes grudgingly), rivalry to be sure, and for many, admiration toward the others’ professionalism. Perhaps the reader will see this relationship, forged during war and peace, as fundamental in developing today’s partnership between the two navies; a partnership that now includes Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. This greater partnership will continue to have major consequences across the world’s oceans during the twenty-first century.

(Return to December 2020 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

- This article is adapted from John Rodgaard and Adam Charnoud, “The Anglo-American Naval Relationship, 1815 – 1837,” in Sean Heuvel and John Rodgaard, eds, From Across the Sea: North Americans in Nelson’s Navy (Winchester, UK: Helion, 2020). ↩

- Christopher McKee, “Foreign Seamen in the United States Navy: A Census of 1808,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 42, no.3 (July, 1985), 383-393. ↩

- Christopher McKee, A Gentlemanly and Honorable Profession: The Creation of the US Naval Officer Corps, 1794-1815 (Annapolis, Maryland: US Naval Institute Press, 1991), xi – 252. ↩

- John B. Hattendorf (ed.), Changing American Perceptions of the Royal Navy Since 1775 (Newport, Rhode Island: US Naval War College, 2014). ↩

- John B. Hattendorf (ed.), “The US Navy’s Nineteenth-Century Forward Stations,” Talking about Naval History: A Collection of Essays (Newport, Rhode Island: Naval War College Press, 2011), 233-234. ↩

- F. Fitzgerald De Roos, RN, Personal Narrative of Travels in the United States and Canada in 1826 with Remarks on the Present State of the American Navy (London: William Harrison Ainsworth, 1827). ↩

- De Roos, Personal Narrative, 10, 15-17. ↩

- De Roos was mistaken about the name of the ship on the building way. The first US warship Susquehanna was a steam-powered warship, which did not see service until 1850. See Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships: “Susquehanna I (Side-wheel Steamer),” Naval History and Heritage Command, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/s/susquehanna-i.html, (accessed 11 July 2017). The Congress was one of the original six frigates authorized by the United States Government. ↩

- De Roos, Personal Narrative, 19, 26-28, 38, 41-42, 61-63, 190-191. ↩

- This monument is the Tripoli or Navy Monument. It presently sits on the grounds of the United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland. ↩

- Rush had demilitarized the Great Lakes with the successful negotiations that led to the Rush-Bagot Convention in 1818. While ambassador to Britain, he acquired expertise in the Royal Navy. Rush became Secretary of State. ↩

- George Jones, Sketches of Naval Life with Notices of Men, Manners and Scenery on the Shores of the Mediterranean in a Series of Letters from the Brandywine and Constitution Frigates, Volume 1 (London: Forgotten Books, 2017; originally published London: H. Howe, 1856), 4. ↩

- Francis Schroeder, Shores of the Mediterranean With Sketches of Travel: 1843-45 (New York: Harpers & Brothers, 1846), digitized on The Internet Archive, 2009 from the collection of Harvard University, https://archive.org/details/shoresmediterra03schrgoog/page/n13 (accessed 31 March 2019). ↩

- Jones, Sketches, 9. ↩

- Jones, Sketches, 9. ↩

- William James Morgan, David B. Tyler, Joye L. Leonhart, Mary F. Loughlin, (eds), Autobiography of Rear Admiral Charles Wilkes, US Navy, 1798-1877 (Washington, DC: Naval History Division, Department of the Navy, 1978), 52. ↩

- Morgan, et al, Autobiography, 53. ↩

- Morgan, et al, Autobiography, 17. ↩

- Jones, Sketches, 30. ↩

- Shroeder, Shores, 4. ↩

- Shroeder, Shores, 5. ↩

- Jones, Sketches, 51, 64, 70. ↩

- Donald L. Canney, Africa Squadron: The U.S. Navy and the Slave Trade, 1842-1861 (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2006), xi-xii. ↩

- Ned and Constance Sublette, in The American Slave Coast: A History of the Slave-Breeding Industry (Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books, 2016), 348, quote Seymour Drescher in his book: Econocide: British Slavery in the Era of Abolition, 2nd ed. (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), that the percentage of American ships engaged in the slave trade was 9 percent in Adam’s administration. Under Jefferson, it expanded to 16 percent. ↩

- Sublette, American Slave Coast, 362. ↩

- Canney, Africa Squadron, 16. ↩

- The tactical pair consisted of a frigate and a brig-sloop. The latter cruised in shallower waters for scouting and capturing slavers operating inshore. ↩

- Canney, Africa Squadron. ↩

- Andrew David, “The Emergence of the Admiralty Chart in the Nineteenth Century,” a paper presented at the International Cartographic Association Symposium on “Shifting Boundaries: Cartography in the 19th and 20th Centuries,” Portsmouth University, Portsmouth, UK, September 10-12, 2008, 3, ICA Commission on the History of Cartography, http://history.icaci.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/David.pdf (accessed 31 March 2019) ↩

- “United Kingdom Hydrographic Office,” Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Kingdom_Hydrographic_Office (accessed 30 March 2019) ↩

- David, “The Emergence…” 5. ↩

- “United Kingdom Hydrographic Office.” ↩

- Beaufort introduced FitzRoy to Charles Darwin; “United Kingdom Hydrographic Office.” ↩

- “Naval Oceanographic Office,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naval_Oceanographic_Office (accessed 30 March 2019) ↩

- “Naval Oceanographic Office.” ↩

- “Naval Oceanographic Office.” ↩