Michael Anderson1

United States Army Officer

In the western military tradition, the popular, common understanding of the Japanese kamikaze of the Second World War inspires images of lone, suicidal modern-day flying samurai knights devoid of empathy with a seemingly fanatical and inhuman desire to die for their emperor. The image of the kamikazes of the Pacific War in a post- September 11, 2001 America are at times compared to terrorists who hijacked and piloted the civilian airliners into the World Trade Centers and the Pentagon, and similar accounts of individual suicide bombers. This comparison is invalid and unfair to the complicated and intricate organization and employment of the Imperial Japanese airborne kamikaze forces of the war, and their effects on the course of the war. The organization and employment of Japan’s airborne kamikaze tokkōtai, or Special Attack Force may appear alien to Western military tradition – and the utility of their impact on the war debated – a deeper understanding reveals a human dimension, longing for life, loyalty, sense of duty, nationalism and strong camaraderie, and an undeniable impact on Allied strategic planning.

Origins of the Kamikaze Organization

In July 1943, Japanese Rear Admiral Kamito Kuroshime presented a proposal at the War Preparation Examination Conference to sanction the use of volunteer suicide attacks. Kuroshime named his plan the ‘Invincible War Preparation’, which at the time, imperial leadership rebuffed. 2 The Japanese command suffered debilitating stalemates or, more importantly, losses such as those of the Battles of the Coral Sea, Midway and Guadalcanal, but the Japanese held faith in a ‘conventional’ victory, or at least a conditional cessation of hostilities. However, the war continued and Japanese losses mounted with General Douglas MacArthur’s island-hopping campaign and Admiral Chester Nimitz’s relentless pursuit of the Japanese Navy. Under this onslaught, Japanese leadership began to rethink their denial of Admiral Kuroshime’s proposal for planned tokkō operations. In March 1944, Prime Minister Hideki Tojō gave the first seriously entertained suggestion of supporting the special attack concept. He ordered the Imperial Japanese Army air corps to begin preparing for ‘special suicide missions’. The first planned suicide mission occurred on the 27 May 1944, when a Japanese plane crashed dived into a U.S. sub-chaser off the west New Guinea coast. 3

The initial, isolated Japanese attack in May 1944 ushered in the official creation of the tokkōtai operation. The tokkō operation, or Special Attack Force, was not an overtly official formation of either the Imperial Japanese Army or Naval forces, but was presented as an all-volunteer corps, similar to the all-volunteer U.S. Flying Tigers unit flying in support of China during the early years of the Sino-Japanese Conflict. The all-volunteer corps removed the normal tradition of all orders within the unit issued “directly” by the emperor through the officers. The intent was to avoid the appearance of the emperor directly ordering these ‘suicide’ attacks, but instead the crews volunteered to conduct them. 4

It deserves mentioning that the Japanese forces were not alone in suicide-missions born in desperation of defeat during the Second World War. As Germany faced an overwhelming onslaught from ground and air, by 1944 their military publications and doctrine became more ideological in tone. Coupled with this change, the Nazi’s air wing, the Luftwaffe, developed similar formations to the Japanese kamikaze force. 5 The missions, labeled ‘extremely high-risk missions’ consisted of a group of standard fighters, stripped to bare minimum of armor and armament, with only sixty rounds of ammunition for one gun, intended to ram Allied bombers over the skies of Germany. The Sonderkommando Elbe or Schulungslehrgang Elbe was Germany’s one formation for these high-risk missions. Though instructed to bail out if practical, this was an extraordinarily dangerous endeavor for these pilots. 6 The specialized ‘ramming’ unit only conducted one recorded operational mission on 7 April 1945. One hundred and twenty German ‘ramming’ fighters- Bf-109s models-, supported by conventional German air support to draw away the approximately eight hundred American fighter escorts from the 1,300 four-engine bombers. This German attack group swarmed an American bomber formation during a daylight raid. Though differing counts exist, estimates hold the bomber force lost thirteen out of 1,300 B-24 and B-17s, costing the Germans fifty-three aircraft and more importantly the associated trained pilots. 7 While the Sonderkommando unit was both conventional airframe and had an intention, however unpractical, for its pilot to survive, the Nazi’s ‘Leonidas’ Squadron, formerly known as the 5th Staffel, Kampfgeschwader 200 group, was an all-volunteer unit. About seventy youths piloting manned versions of the V-1 rocket, old bombers, and even attack gliders formed the unit. The ‘Leonidas’ Squadron was billed as the total-commitment mission force with the volunteers knowing it as a suicide formation. Although the idea formulated for this unit in late 1944, after prolonged training and increased indoctrination, Germany never used them, and the formation disbanded. 8 However, this distinct difference separated the German flirtation with suicide units from that of the Japanese in that Imperial Japan organized, trained, and extensively utilized their suicide formations.

Captured Japanese Kaiten Type-1 Human Torpedo at Ulithi Atoll in 1945. Forward portion warhead, oxygen and fuel tanks and crew compartment missing. (U.S. Navy. National Archives Collection photo #: 80-G-350027)

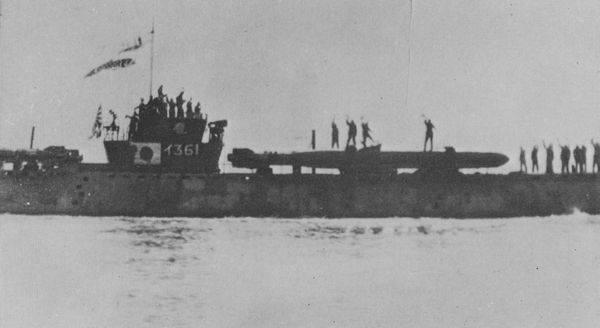

The tokkōtai operation over all encompassed more than the just the well-known aerial kamikazes, operations included more than planes crashing into ships. The operation included two types of aerial attacks, conventional planes such as the famous Zero fighter plane being purposely piloted into Allied ships as well as specifically designed oka (‘cherry blossom’) piloted bombs dropped from a mother-plane once near a viable target and then guided into the enemy ships by its volunteer pilot. Kamikazes came not just from the sky, but even below the water with seaborne attacks like the kaiten (‘heaven shifter’) minisubs, essentially piloted human torpedoes 9 and the shin’yōs (‘ocean shaker’), a plywood motorboat stuffed with a warhead for ramming Allied ships. 10 Even the Japanese Army contributed to this concept, beyond even the normal final banzai charges of isolated garrisons, they conducted limited, specific planned tokkō attacks, such as the airborne assault against a U.S. airfield on Okinawa. The Japanese transport planes crash-landed on the U.S. runway and the Japanese Army paratroopers burst out, tossing grenades and firing small arms destroying and damaging as many U.S. planes as they could before being killed. 11 Though there were many programs, the most pervasive was the traditionally understood aerial kamikaze, resulting in this focus with limited comparisons to the other operations.

Initiation of Organized Kamikaze Operations

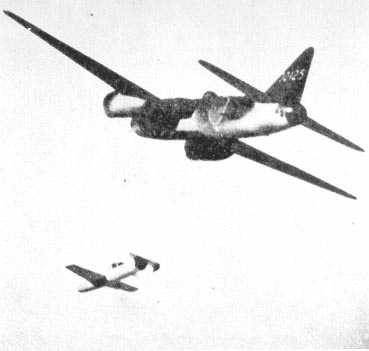

The tokkō operation officially initiated in October 1944, even as the oka, the specifically designed piloted-bomb dropped from a Mitsubishi Type-1 Attack Bomber (Betty), remained in testing. Customized Betty bombers carried the okas slung underneath with the kamikaze pilot inside and escorted by fighter cover until nearing viable enemy targets. Once the crew identified a target, the kamikaze pilot crawled through the bomb bay doors and into the oka for release. After release from the mother-plane, the kamikaze pilot guided the flying 250-kilogram bomb into the enemy ship. 12 Vice Admiral Takijirō Onishi, commander of the Philippines aerial defence, strongly supported the concept of the oka, arguing persuasively they could not wait for the oka to go fully into production and needed to approve utilization of conventional aircraft until the okas were available en masse. His arguments resulted with the formation of the Kamikaze Special Attack Corps in the Philippines manned by volunteers. 13

Japanese G4M Type-1 “Betty” Bomber launching an Oka. (Imperial Japanese Navy, unknown date. Public Domain.)

Admiral Onishi held operational control of the tokkōtai for use in defense of the Philippines. He coordinated the planned employment of the first kamikaze forces for Japan. The dire military situation of Japan led to this historically unprecedented embracement of organized suicidal attacks. 14 After the massive Battle of Leyte Gulf in the Philippines, the Imperial Japanese Navy ceased to be a viable option for Japanese victory, or at least achievement of a negotiated settlement. In Leyte Gulf, the Japanese lost four carriers, three battleships, ten cruisers, twelve destroyers, four subs and numerous land and seaplanes. The use of conventional planes as kamikazes, the first ones of the newly sanctioned Kamikaze Special Attack Corps, gave the only hint of success during the operation to delay the Allied retaking of the Philippines. 15 The Japanese leadership concluded extreme measures were needed due to the heavy losses sustained in the war, and the inexorable Allied campaign encroaching upon the Japanese Home Islands.

The Allied advances slowly placed the Home Islands within range of U.S. bombers. The now regular and damaging air raids, conducted mainly by the large B-29 Super-fortresses operating out of captured island airfields and free-China, led the Japanese to extreme measures attempting to halt the Allied advance. 16 The Japanese forces suffered from a massive loss in skilled pilots through aerial attrition. United States labelled it as the ‘Great Marianas Turkey Shoot’, officially the Battle of the Philippine Sea, epitomized the damage to the Japanese cadre of pilots with 243 of 373 Japanese planes lost along with their veteran crews compared to 29 U.S. losses. This further drove the Japanese to the kamikaze concept. 17 The American kill ratios in the air, especially after the Marianas-induced losses of veteran Japanese pilots, contributed to many Japanese leaders believing all flight missions were potentially suicidal, or ‘one- way’ without much chance of return. 18 The Japanese identified their last hope to defend the Home Islands being to force the U.S. to a conditional cease-fire by increasing the Allied losses in general but specifically with targeting the Allied aircraft carriers to limit U.S. air superiority. With this goal, the Japanese embraced the kamikaze concept: one plane, one ship. Japanese aircraft production increased throughout the war even as veteran pilots decreased, leading the Japanese to recruit unskilled pilots for kamikaze duties. It took less flight training to teach a pilot to simply take off/land and crash-dive into a ship, compared to the complexities inherent in successfully surviving aerial dogfighting. 19 Once the Japanese determined to officially endorse kamikaze operations it was only a matter of how to recruit the pilots and crews.

The Recruits

Broadly, three types of people staffed the kamikaze units – fully aware volunteers, uninformed volunteers, and later, due to losses, conscripts. At the onset of organization, fully informed volunteers knowing exactly what they were volunteering for signed up. The original targeted audience for this first call to join the Special Attack Forces was small-craft flight instructors, both officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs), mainly petty officers in the Navy. Once they volunteered, the Japanese military categorized these individuals as ‘very eager’, ‘eager’, ‘earnest’, or ‘just compliant’. The Japanese authorities considered those who signed their volunteer request in blood ‘very eager’. These applicants received further evaluation on comprehension, judgment, and decision-making abilities as ‘excellent’, good, or ‘just fair’. The Personnel Bureau of the Naval Ministry maintained the records of the volunteers. 20 As the losses within the Special Attack Force mounted during the initial employment in the Philippines Campaign, the ranks of volunteers thinned. With the Japanese command’s positive response on the returns during the inaugural organized kamikaze attacks done by volunteers in conventional planes, the specifically designed oka production increased along with its pilot ranks.

The oka unit formed officially in October 1944 along with the initial organization of Admiral Onishi’s conventional Kamikaze Special Attack Corps for defense of the Philippines. The oka unit, based out of the Home Islands, was known as the Thunder Gods Special Attack Corps, numerically designated the 721st Naval Flying Corps. 21 The oka unit was a mixed unit of volunteers with the inclusion of conscripted pilots. The other classification of volunteers, the uninformed, knew they were volunteering for tokkō operations but it would not be until they already signed up and walked down the tarmac that they were informed exactly what it had meant that they volunteered for when they came in sight of the oka, the ‘flying-bomb’ – clearly designed for one thing. 22 The oka organization totaled four thousand pilots, the so-called ‘boy pilots’ made up around three thousand of the oka pilots. These ‘boy pilots’ were conscripted teenage youths or young volunteers whose education had been discontinued to allow for their conscription or enlistment. They were enlistees, not officers, enrolled in special programs designed to train young boys to accept becoming kamikazes. 23 In contrast to similar programs teaching suicide prevention, these programs surrounded young minds with peers to encourage the youths to embrace their calling to become tokkō pilots. 24

Other than the boy pilots, the ‘student pilots’ made up the other one thousand pilots of the Thunder Gods oka corps, drafted students of Japan’s universities. They graduated early to make them available to the draft. Highly educated, there was no favoritism involved, the student pilots came from even the most prestigious of the Japanese schools, drawn from arts and humanities academic majors, allowing for the science and technology graduates to be drafted to work in the military’s research and development sectors. 25

A Japanese MXY-7 Model 11 Okha suicide plane captured on 1 April 1945 at Yontan airfield, Okinawa. (U.S. Navy, dated 1 April 1945. Public Domain.)

The earliest volunteers, the experienced small craft pilot trainers, knew exactly what they were getting themselves into, while those unsure early volunteers who only wanted to fly to avoid service in the ground forces. There was definitively trepidation among the conscripted pilots on the final walk to the planes. Through the days of training, long days waiting for names to be chosen, watching others go to never return, and sometimes multiple sorties required to find a target, resulted in plenty of time to second-guess an earlier decision no matter how enthusiastically, or ‘eager’, it had been made, written in blood or not. The psychological effects of multiple aborted missions due to mechanical or weather complications coupled with the dramatic send-offs after mild sake toasting with white linen draped tables and Japanese young girls waving cherry blossom branches only added to the already mounting internal stress on the pilots. 26 Their determination torn between a will to live and devotion to duty and cultural expectations equaled an unbelievable and difficult psychological struggle.

Devotion to Duty and the Will to Live

On the day leadership chose him to conduct an oka mission, one of the Thunder Gods pilots riding in the truck alternated between boasting of his bravery and coming glorious crash-dive with a cry of ‘Mother! The Navy is trying to kill me!’ 27 This sort of inner struggle between the innate human will to live with the societal and cultural expectations and encouraged sacrificial action, was common in the kamikaze corps, mostly with the conscripted boy pilots and the student pilots. However, this sort of psychological battle within the Japanese pilot was likely a reality at some point for all kamikaze crews.

Other examples of the kamikazes will to live involved abuse of the recurring maintenance issues plaguing all Japanese aerial operations towards the end of the war. Engine troubles, landing gear retraction failures and poorly mixed fuels along with foul weather routinely terminated kamikaze sorties. Many times mechanical failures depleted kamikaze formations long before they reached the enemy’s forces. Weather, fuel, or mechanical issues forced many kamikaze pilots to turn around and return to base, awaiting another rendezvous with destiny, ostensibly with a fixed plane or better weather. However, some kamikaze pilots repeatedly suffered instances of ‘imagined’ mechanical failures or consistent ‘poor visibility’ conditions, leading to charges of cowardice from the command. The charges strove to avert a fear indirect non-compliance with kamikaze orders may spread among the force, and damage overall Japanese morale as the public learned their kamikaze ‘volunteers’ were not always so ‘eager’. As a result, the Japanese command sent these ‘repeat offenders’ on solo missions without air cover and told not to return, or if they had multiple offenders, the Japanese command grouped them together and sent them on missions without accompanying air cover, easy targets for the American fighter patrols. These kamikazes’ exploits remained unrecorded and unknown in contrast to the standard procedure of the other kamikaze exploits reported directly to the emperor. 28

Contrary to popular myth, the aerial kamikaze forces did not embark upon their missions with only enough fuel for a one-way trip. The ‘one-way fuel’ is not entirely accurate and is a belief that may have originated and been encouraged in the West to support the portrayal of a Japanese ‘callous disregard for life’. This was an easy way to rationalize the organization and employment of kamikazes by the desperate Japanese forces. The fundamental aspect of the Special Attack Force concept was not one of suicide or even ‘glorious’ death, rather a coordinated, planned, tactical application of a strategic military concept as Japan’s last chance to avert total defeat. 29 In actuality, if not in concept, kamikaze operations were essentially ‘suicide’ missions, but within the overarching Japanese command view on the operations it is clear to see they were organized and planned efficient military operations. Full fuel tanks only added to the damage sustained by an enemy ship if successfully struck by a kamikaze, but also full fuel tanks allowed for kamikazes who failed to locate enemy ships to return to their airfields and sortie again another day to potentially strike the enemy later. 30

Cultural Influences on Kamikaze Motivations

There are a multitude of different factors to consider when determining what may or may not have motivated the kamikaze pilots. Each pilot was an individual with his own mind, logic, and sense of duty and devotion. Contrary to certain Western perceptions, the kamikaze pilots were not mindless automatons, drunken, drugged, or chained into their cockpits to undertake these missions. 31 One of the most commonly proposed is the influence of bushido on the Japanese culture, especially the military.

Bushido was a code of conduct harkening back to a sacred past of Japan, the samurai. Highly idealized, the way of the warrior- bushido- illustrating the convictions and lifestyle of the samurai, blossomed into a national code of conduct. Due in large part to the historical role of the samurai as the guardians of Japan and the elite warrior class of Japanese history, it was natural their code played an integral part in modern Japanese military system and culture. At its core, bushido incorporated Buddhism, Shinto and Confucian beliefs- core Japanese religions- into a code of conduct for the samurai. With the modern Japanese presenting their military as the descendants of brave and dedicated samurai, bushido played a significant role in the mind-set of all Japanese military and especially those preparing themselves to make the ultimate sacrifice.

Bushido was technically an unwritten code, simply an understanding of expectations for the life of a samurai. The two major factors bushido imparted to the motivation of the kamikaze were the sense of duty to Japan and authority, acceptance of death, and the honor in so doing. Buddhism, Shinto and Confucian beliefs played important parts in forming the core of bushido. Bushido added to the military mind-set of Second World War Japan the role- or duty- known as Giri. This giri drew from the major pillars of Japanese culture: the concept of duty to parents, superiors, inferiors and society above oneself.

Bushido formed a core to the Imperial Code of Military Conduct, fully instituted by the Meiji empire by 1882. The original imperial code of conduct had five main elements: loyalty, propriety, courage, righteousness, and simplicity that guided Japan’s warriors, rooted in traditional bushido practices. In the early 1900s, however, the code and bushido’s role in it changed with the new generation of modern Japanese military leadership. Unlike the Japanese military and political leaders of the late 1800s, the harbingers of the evolution from samurai Japan to modern westernized Japan, these new leaders lacked experience or practice of traditional bushido. Instead through attendance to new military academies and experiences with larger, peasant conscript armies, these leaders embraced the doctrines of western influence while merging it with manipulated and modified aspects of traditional bushido past, linking the modern Japanese military with that of its idolized pre-20th Century samurai warriors.

The main element in this shift was the corruption of the loyalty to state and nation to now conform to the dominant “emperor ideology”, a blind obedience to whatever the emperor said, as commanded through his officers. Instead of the original code’s five main points, now this modified and manipulated code emphasized no surrender, blind obedience, and honor in dying for the emperor. The codification of this shift came from 1908-1913 as imperial military regulations changed, incorporating this new modified form of blended western doctrines with isolated, corrupted bushido principles. 32

Buddhism imparted ‘a sense of calm, trust in Fate, a quiet submission to the inevitable, that stoic composure in sight of danger or calamity, that disdain for life and friendliness with death’, something that was clearly applicable to the kamikaze situation. 33 Incorporating Shinto beliefs into bushido achieved the infusion of ‘such loyalty to the sovereign, such reverence for ancestral memory’ to provide the expectation of complete obedience. For the Japanese military, and especially the Special Attack Forces, this provided the necessary expectation of obedience through loyalty to authority and respect for ancestors exemplified through an overwhelming patriotism. Confucius beliefs added another crucial aspect to the role bushido played in motivating and legitimizing the Japanese kamikaze practices. Confucian beliefs provided the ethical foundation, the most influential aspect being the Five Moral Relations, which relevant to the kamikaze undertaking emphasized the ethics and responsibilities of the governed (the pilots) to the governing (the command). 34

With this sense of duty and the acceptance of the costs, bushido gave the kamikaze pilots the concept of honor in their actions associated with their execution of their duties and the resulting costs. Nitobe in his classical work on bushido titled Bushido: Soul of Japan summed up the role of bushido in establishing the sense of honor with which the kamikaze pilots saw their actions as rewarding. He wrote on honor and bushido, ‘Life itself was thought cheap if honor and fame could be attained therewith; hence, whenever a cause presented itself which was considered dearer than life, with utmost serenity and celerity was life laid down.’ The key emphasis to the use of bushido inducing kamikaze pilot’s compliance with their missions was clear: to present tokkō as a cause ‘dearer than life’ with which ‘honor and fame’ could be achieved and would have Japanese soldiers accepting those missions ‘with utmost serenity and celerity’. 35

This directly influenced the cultural expectations of Japanese military men in wartime. When it comes to analyzing the motivations behind, the feelings and thoughts of kamikaze pilots there is a certain impasse, the challenge of limited explanation in their own words. The kamikaze pilots who fate never called before the end of the war can pass on their accounts, and the reasoning, motivations of the ones who actually undertook the kamikaze missions can live on in the diaries and letters of the student pilots, being highly educated and literate graduates of Japan’s top universities. They were the ones drafted into the tokkō operations and left an abundant of written work illuminating their struggles with the kamikaze concept. The only ones whose voice is lost to history are those of the boy pilots. Under educated, they left little literature documenting their thoughts and feelings. 36

In the words of the student pilots, it becomes clear the role of culture influenced by bushido values played into the reasoning, legitimizing, and struggle of acceptance. In a letter to his mother, a young drafted student and oka pilot named Ichizō wrote, ‘Mother, I am a man. All men born in Japan are destined to die fighting for the country. You have done a splendid job raising me to become and honorable man. I will do a splendid job sinking an enemy aircraft carrier.’ Elsewhere he wrote, ‘Mother, please be pleased that someone like me was chosen to be a tokkōtai pilot. I will die with dignity as a soldier.’ 37

In his dairy, Ichizō wrote on 23 February 1945, ‘I have dreaded death so much. And yet it is already decided for us. My environment in the past was beautiful. So I feel I can die dreaming. But when I think of my mother, I cannot help but cry… When I think of my mother… I cling to life.’ In a later entry dated 2 March 1945, he wrote, ‘I dreamed of my death in a fierce battle. My only wish is to die for the emperor.’ The internal struggle between duty and the cultural expectation with the natural human desire to live is clear in the words left behind by some of the tokkō pilots.

20th Century Reality: Nationalism and Fatalism as Motivation

Some pilots completely disregarded the emperor-centric ideology, such as the Christian Japanese pilots, while others found final solace in accepting the inevitable. One student wrote, ‘There must be some peace of mind for dedicating my life to the emperor… To be honest, I cannot say that the wish to die for the emperor is genuine from my heart. However, it is decided for me that I die for the emperor.’ Without accepting the emperor-centric ideology, or even not accepting the traditional Japanese religions, Japanese Christians still actually volunteered for the tokkō operations. It was not religion, or even culturally based at times. The motivations for service in the tokkō units were at times simply patriotic nationalism. Some of these Christian pilots quoted Bible verses in their letters and sang hymns in their cockpits. 38

There was also a shared and strong sense of fatalism, both with their individual circumstances for those drafted as well as the overall situation for Japan, which affected the volunteers. By the time the tokkō operations became official in autumn 1944, most pilots had seen their friends already die, they knew the war was lost for Japan and tired of being upset, to them death would be a release of emotions. 39 When it came to the conscripted pilots, their fatalism was of a different strand. The first lessons one conscript learned when he arrived at the Tsuchiura Naval Base for induction was how to kill himself with his own rifle. This was a resulting air of finality taught from the Imperial Military Code, which declared surrender, escape, escape even from ultimate defeat, was punishable by death. Disobedience was instant punishment, as obedience was a foundational expectation from bushido. If they returned without finding a target there was the possibility of execution, but normally just sent back out repeatedly. Simple refusal to go on the missions routinely led to reassignment to the ground forces and transfer to the island garrisons, which many equated to suicide just as much as kamikaze missions. Not only was the soldier liable for punishment, but it could extend to the family. This led to the added social pressure on the service member for complete, unwavering obedience, if not for themselves then at least for their families. 40 Even so, in defiance, some pilots buzzed the command’s quarters in a defiant final gesture of their hatred for their leaders who sent them to their deaths while they remained behind. Some even tried crashing into the water near the coast in order to live. 41

On top of this, there was the allure of rewards. Fatalism inspired the cult of a hero’s death. Imperial Japan posthumously promoted kamikaze pilots by two ranks, and in their death families received the payments, so in death they not only provided for their families for the future but with increased salaries than if they had lived. This gave some of the less well-to-do individuals an incentive with which they could fulfil the cultural expectations of taking care of their families just by ‘dying a hero’, which they could not fulfil in life. In line with this system of punishments and rewards, there can certainly be made the claim authorities coerced kamikaze pilots. 42

Kamikaze Operations and Impacts on the Pacific War

As shortly as two hours after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, a Japanese pilot purposefully drove his plane into a U.S. ship. The seaplane tender, U.S.S. Curtiss, fought off a midget submarine and multiple Japanese dive bombers, with one damaged plane crashing into the deck. The Curtiss suffered fifty-four casualties during the Pearl Harbor attack. 43 At the time, it was not official Japanese war policy and isolated, individually spontaneous suicide attacks such as these were known as kesshi, or ‘dare-to-die decision’. 44 However, when assessing the effects of the official tokkō operations on the conduct of the Pacific War there are essentially three major engagements in which Japan used mass aerial kamikaze forces: the Philippines Campaign, Battle of Iwo Jima, and the pinnacle of kamikaze employment during the war during the Battle of Okinawa. Japan organized and coordinated the tokkō operations within the larger strategic plan. They were not attacks made in isolation or in some sort of tactical or strategic vacuum. Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki pioneered many of the tactical employments of the kamikazes, calling them the ‘First Tactics’. First, radar-equipped scout planes went out to locate the enemy fleet at night. After locating the enemy fleet, the conventional torpedo planes attacked at dawn. This tangled up and diverted the Allied air cover and shipboard defensive armaments. The final strike came from a wave of kamikaze aircraft striking during the height of the day-light hours for best results, making it more difficult for gunners to defend the ships and easier for the pilots to locate targets. 29 Critical to the survivability of the kamikazes to impact was cover from supporting fighters to keep the superior U.S. Navy Hellcats and Corsairs from slaughtering the inexperienced Japanese pilots. Although some believed these escorts served other purposes as well, such as assuring the kamikazes carried out their attacks, not turning back, most agree they were there to provide support and record efficiency of the attacks. 46

The kamikazes received direction that the aircraft carriers were the first priority, and specifically to target the vulnerable and crucial elevators on the flattops. Even if the kamikaze did not put the carrier out of action by their hits, the damage done by the water and foam used to put out the fires kept the decks useless for weeks. Perhaps not sinking, but at least putting the carrier out of the action for a period. During these attacks, many times Allied sailors pulled the Japanese pilots’ bodies from the wreckage on the Allied ships. 47

The first coordinated, massive kamikaze aerial operation of the war was in defense of the Japanese-occupied Philippine Islands, during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. There had been other impromptu suicide attacks before, but the Philippines Campaign, and more specifically the Battle of Leyte Gulf, was the first sanctioned and coordinated use of kamikazes. At Leyte Gulf, the casualty ratio was approximately 11:1, 131 U.S. casualties to 12 Japanese kamikaze crewmembers lost. The Japanese kamikazes at this early stage in the tokkō operations utilized conventional planes, and twelve conventional planes-turned flying bombs struck four light carriers, sinking one, the St. Lo. Of the 131 U.S. casualties, 114 came from the loss of the St. Lo alone. 48 At the time a U.S. Navy captain scoffed in an after action report commenting that the so-called ‘suicide dives’ were ‘a stupid way to attack because it has less a chance of getting home than other types of bombing’. 49

By the conclusion of the Philippines Campaign, the airborne kamikaze-caused U.S. casualty (killed and wounded) tallies of 763 at Leyte Gulf, 470 at Mindoro, and 167 at Lingayan Gulf, including an U.S. admiral, several Australian allies, and Winston Churchill’s personal representative, Lieutenant General Herbert Lumsden. 50 During the Philippines Campaign, the tokkō operation commenced haphazardly, but during the subsequent Battle of Iwo Jima the kamikazes maintained a significant presence. At Iwo Jima, roughly twenty-four recorded kamikaze attacks resulted in hundreds of casualties. In isolated attacks, kamikazes even went as far as the Truk Islands harbor where the U.S. carriers returned for rest and refitting. Between the introduction of organized kamikaze attacks during the Philippines Campaign and the commencement of the Okinawa Campaign, U.S. casualties due to the airborne tokkō operations reached 2,200 personnel, virtually all naval personnel. 51

The Okinawa Campaign marked the pinnacle of tokkō operations during the Pacific War. Leyte Gulf had been the trial and error period of employment, Iwo Jima had caught the corps reforming and regrouping after the Philippines Campaign, but it was at Okinawa where the Allies felt the full brunt of the Special Attack Force. 52 Between 6 April 1945 and 10 June of the same year, there were ten mass kamikaze attack formations numbering between fifty to three hundred aircraft targeting the assembled U.S. Navy around Okinawa. Because of this, approximately five thousand U.S. sailors died from kamikaze attacks, the highest losses the Navy had sustained in any battle during the war. 53 In comparison, the U.S. Army on Okinawa lost about four thousand soldiers, and the U.S. Marines lost nearly three thousand. The U.S. Navy lost 763 airplanes, many destroyed on the decks of their flattops from kamikazes, and 38 ships sunk, along with 368 ships damaged, with the casualties adding up to equal the aforementioned 5,000 deaths and nearly twice as many wounded. The losses sustained due directly to the kamikaze planes was so shocking the U.S. government kept the damage secret from the public right up until the cessation of hostilities, ostensibly to protect morale. 54 This reversal of the traditional casualty rates from the previous island-hopping campaigns led to increased tensions between the naval commanders and the ground commanders. Admiral Nimitz’s comments to the U.S. Tenth Army commander, General Simon Bolivar Buckner, showed the frustration, claiming the Navy lost ‘a ship and a half a day’ at General Buckner’s allegedly lethargic pace of advance on Okinawa. 55 Beyond just the physical damage done to the wounded and the fatalities, the U.S. Fifth Fleet at Okinawa suffered battle stress casualties at levels unmatched before or after, from land or sea engagements due to the immense tension and fear associated with the kamikaze planes. 54

During the Okinawa Campaign, the first use of the specifically designed oka flying bombs emerged on the battlefield. Overall, the okas effectiveness left the Japanese command unimpressed. The statistics for the okas’ use at Okinawa was 1 U.S. destroyer sunk, 6 other U.S. ships damaged for a loss of 375 Betty mother-plane crewmembers and 55 oka pilots. 57 The U.S. destroyer, the only ship sunk by an oka, was the Mannert L. Abele, split in half by the oka’s warhead, sinking in three minutes, testimony to the destructiveness of the more powerful oka warhead when compared to the conventional plane-turned kamikaze, bit only when it struck its target. It was the delivery method and limited maneuverability of the oka in comparison to the conventional Japanese planes cancelling the benefit from the stronger warhead. 58 Even still, the damage inflicted on the U.S. Navy since the onset of the tokkō operation during the Philippine Campaign was without question grim.

Allied Tactic Response to Kamikazes

The low estimate of Allied casualties at Okinawa due to the kamikaze attacks equaled 3,389 U.S fatalities along with 26 British losses, whose steel decks on their carriers afforded better protection when compared to the wooden decks of the American ships. 59 It was serious enough that it led the U.S. command to adjust its conduct of the Pacific War. The damage led to changes in the U.S. battle plans and task organization. The first lesson learned was the importance of fighter protection to bring down the kamikazes as far from the fleet as possible, striking the kamikazes at their bases while on the ground. This meant adding more interceptor aircraft to carrier compliments at the expense of attack aircraft, such as fighter-bombers and torpedo planes. 59

The tactical countermeasure used to combat the kamikaze threat started with an increased patrol range and number of planes in the CAP (Combat Air Patrol) out beyond the assembled fleet. These CAPs comprised Navy and Marine fighter-interceptors, later Army Air Corps planes after airfields taken on Okinawa placed Army planes within range to support. This curtain of fighter protection, dubbed by many as the ‘Big Blue Blanket’ because of the blue paint jobs on the Navy planes, pounced on the incoming tokkō plane formations as far from the U.S. fleet as possible by direction from a series of concentric picket lines manned by radar-equipped destroyers. The picket line concept succeeded to an extent by cutting down on the amount of kamikazes that made it to the main fleet to attack the carriers or troop transports, but inevitably led to the kamikazes ferociously attacking the picket destroyers as targets of opportunity and causing massive casualties within the picket lines. On Picket Station 1, the average expectancy after a Japanese offensive was six hours before a kamikaze hit a destroyer. 61

Other dangers existed as well. The common anti-aircraft measures did not work against the kamikazes since their design was for conventional threats. This meant the anti-aircraft weapons caliber were only big enough to bring down a kamikaze on the larger ships, those with 5-inch guns, and the act of zigzagging and conducting evasive maneuvers at high speeds threw off the aiming of all but the most advanced radar-equipped gun-direction systems. The need for larger caliber anti-aircraft coupled with the standard procedure of massing multiple ships together to form the tightest collection of gun coverage, led to a marked increase in ‘friendly fire’ incidents as shrapnel and shells from neighboring ships’ anti-aircraft guns rained down on other ships killing sixty-five and wounding three hundred and sixty-eight. 62

Japanese submarine I-361 with Kaiten attached at Hikari Naval Base. (Imperial Japanese Navy, dated 23 May 1945. Public Domain.)

The other adjustment to the U.S. Pacific War plan due to the emergence of the tokkō operation to the scene was the reassignment of two thousand B-29 bombing sorties from urban targets to identified tokkō airbases. These air raids successfully delayed some kamikaze sorties but at the cost of postponing the urban center raids, which remained the strategic priority for the bombing force. 63 Evidence supports the kamikazes flew even from pot-marked runways in order to carry out their missions, questioning the actual effectiveness of the bomber strikes against the kamikaze airfields. During the commencement of the official tokkō operations from October 1944 to the cessation of hostilities, 2,550 missions sortied, of which 475 successfully hit or had damaging near-misses, roughly an 18.6% hit rate. Overall, the airborne kamikazes damaged twelve aircraft carriers, fifteen battleships, sixteen light carriers; however, none larger than the escort carrier St. Lo sunk. The total sunk amounted to forty-five ships, mainly the destroyers operating the picket lines. 64 The final tally of the airborne tokkō operations varies but one account places it at 6,310 Japanese lost with 15,000 combined Allied casualties. In perspective, the kaiten amounted to less than two hundred Allied casualties for one thousand Japanese lost in kaiten operations, this including the crews of eight conventional submarines sunk trying to launch kaitens, and those dying in training. The sinking of the destroyer escort Underhill in the Philippine Sea demonstrated the destructive possibilities from a kaiten strike, splitting the ship in half, killing 112 sailors, nearly half the crew; however, kaiten operations rarely succeeded. The Japanese conducted ten major kaiten operations, most of which were miserable failures aside from the sinking of the Underhill. Kaitens sunk two other American ships, the U.S.S. Mississenewa oiler and an infantry landing craft. The Mississenewa was struck on 20 November 1944 in the first kaiten attack, losing sixty-three men, while the LCI-600 sinking killed three Americans. The cumulative loss of Americans from kaiten attacks totaled 181 Americans. 65 The arrival of the tokkō planes, in comparison, no doubt effected the unfolding of the war in the Pacific in many ways.

Allied Operational Response to the Kamikazes

According to the United States Strategic Bombing Survey: Pacific War Summary, the Japanese military had amassed approximately 5,000 tactical planes and 5,400 specifically designed kamikaze aircraft for use in the final invasion, with an additional 1,000 kaitens prepared to strike from undersea. 66 Intelligence intercepts from the code-breakers at Ultra determined the Japanese intended to target the troop transports as their main priority in the defense of the Home Islands, a switch from targeting aircraft carriers first. This switch showed shrewd Japanese calculations as the transports were slow moving, lightly armored and by their mission naturally stationed nearest the shore. 67 The change in focus of their attacks to exponentially inflict most possible casualties on Allied forces even came at expense of tactical victory by shifting from carrier to troop transport targets. This, without question, concerned a casualty-wary U.S. leadership this close to victory, having already obtained victory in Europe earlier in the year. The Japanese without a doubt, passed desperation and embracing refusal to admit unconditional defeat, amassed more planes than Allied planners initially anticipated before the intelligence intercepts. 68

Without a doubt, the costly success of the tokkō operations against the Allied forces played a role, among other critical factors, in the decision to use the atomic bombs and thus avoid the final showdown and bloodletting inherent in an invasion of Japan. The kamikaze toll during the Okinawa campaign so shocked the U.S. Navy leadership that chief of naval operations, Admiral Ernest King, withdrew his support for an invasion, conceding to the order to put it in motion as an option, but instead championed for a different route to victory, be it blockade, aerial bombardment or ultimately the atomic bombings. King was not alone in this, chief of the Pacific Fleet, Admiral Nimitz also withdrew his support to an invasion after the Okinawa experience. 69

Twilight of the Kamikazes

The last kamikaze of the war struck at 1456 local time on 9 August 1945. He made it through the CAP and the anti-aircraft fire off the Miyagi Prefecture along the central Honshu coast of Japan to strike the destroyer Borie. This final strike killed forty-eight U.S. naval personnel and wounded sixty-six. With the last kamikaze passed history’s first example of an organized and coordinated effort to conduct tactical suicide missions in support of an overall strategic plan supporting a nation state’s military. 70 Neither of the two most vocal promoters of the tokkō operations, Admirals Ugaki and Onishi survived the war. Ugaki was last seen taking off on a final kamikaze mission in defiance of the emperor’s order for peace. Onishi committed ritual suicide rather than face defeat. 71 Earlier in the war, Onishi wrote,

In blossom today, then scattered

Life is so like a delicate flower

How can one expect a fragrance

To last forever 72

A surviving kamikaze pilot, Tashio Yoshitake, whose name Fate had not drawn for a mission before the end of the war, said, ‘I’ll tell you what war is. It’s a situation in which a person has absolutely no control over their own destiny. Everything is out of your hands. You can’t stay alive when you want to, but you can’t die when you want to, either.’ 73 The humanity of the tokko pilots is clear that by the time the war was nearing its end and the remaining pilots had seen so many of their comrades fly to their deaths but they themselves had remained behind no longer sung patriotic songs before the missions, instead they sung the ‘Lullaby from Itsuki’:

I long for the day I can return to my beloved parents when my service is over.

I am here far from home.

Even when I die, no one will cry for me.

How lonely it is only to hear cicada cry.

No one will come to visit my tomb.

Then I am better off buried along the road,

Since someone might offer flowers.

I don’t care which flowers the offer. Perhaps camellia blooming in the wild

Along the road, no water is necessary, since it will rain. 74

Though the kamikaze forces of Imperial Japan may seem on the surface organized and utilized in a military manner uncommon to Western military customs, the human element of the Special Attack Force subscribed to eerily similar beliefs as those of Western military tradition, and the desperation leading to their utilization is not uncommon in the Western military traditions. In any case, the impact made on the war in the final months of the war by this organization was undeniably influential in the decision-making process for the U.S. military in the final days of the Second World War in the Pacific.

(Return to December 2020 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

- The author wishes to acknowledge and express appreciation to W.E. from the Library of Congress main reading room, James Zobel archivist at the MacArthur Memorial Archives, Nathaniel Patch archivist from National Archives, and Dr. Charles Chadbourn III from the U.S. Naval War College for their timely support, recommendations, and encouragement in this manuscript during these challenging research days. Also wish to thank Megan Wood for critical review and research assistance. The end result greatly benefited from this help. ↩

- Hatsuho Naitō, Thunder Gods: The Kamikaze Pilots Tell Their Story (New York: Kodansha International, 1989), 22. ↩

- Naitō, Thunder Gods, p. 23 ↩

- Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikaze Diaries: Reflections of Japanese Student Soldiers (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), p. 6. ↩

- Richard R. Muller, ‘Losing Air Superiority: A Case Study from the Second World War’, Air and Space Power Journal, Winter 2003, p. 59. ↩

- Muller, ‘Losing Air Superiority’, and Michael Peck, ‘Hitler’s Kamikazes: Nazi Germany’s Suicide Aircraft’, The National Interest, 16 July 2016. ↩

- Muller, ‘Losing Air Superiority’, p. 60, and ‘Hitler’s Kamikazes’. ↩

- Muller, ‘Losing Air Superiority’, p. 60. ↩

- Natiō, Thunder Gods, p. 23. ↩

- M.G. Sheftall, Blossoms in the Wind: Human Legacies of the Kamikazes (New York: NAL Caliber, 2005), 432. ↩

- Naitō, Thunder Gods, 176 and John Toland, The Rising Sun, Volume 2: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936-1945 (New York: Random House, 1970), pp. 882-883. ↩

- Naitō, Thunder Gods, p. 34. ↩

- Naitō, Thunder Gods, pp. 57-58. ↩

- Sheftall, Blossoms in the Wind, p. 28. ↩

- Sheftall, Blossoms in the Wind, p. 68-69. ↩

- Sheftall, Blossoms in the Wind, pp. 28-29 and Gerald Astor, Operation Iceberg: The Invasion and Conquest of Okinawa in World War II (New York: Dell Publishing, 1995), p. 173. ↩

- John Keegan, The Second World War (New York: Penguin Books, 1989), p. 307. ↩

- Sheftall, Blossoms in the Wind, p. 58. ↩

- United States Strategic Bombing Survey: Summary Report (Pacific War) (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1946), p. 9. ↩

- Naitō, Thunder Gods, pp. 43-44. From a mirror-imaging cultural perspective, it can be difficult for some cultures to image the assessment of ‘compliant’ volunteer for kamikaze missions with ‘fair’ judgment and decision-making abilities, or of the written in blood ‘very eager’ kamikaze pilots obtaining an assessment of ‘excellent’ comprehension, judgment and decision-making abilities, but this would be assigning cultural bias in observation and understanding. ↩

- Naitō, Thunder Gods, p. 54. ↩

- Sheftall, Blossoms in the Wind, p. 154. ↩

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikaze Diaries, p. 1-2. ↩

- Astor, Operation Iceberg, p. 173. ↩

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikaze Diaries, p. 2. ↩

- Sheftall, Blossoms in the Wind, p. 63. ↩

- Naitō, Thunder Gods, p. 172. ↩

- Sheftall, Blossoms in the Wind, p. 291. ↩

- Naitō, Thunder Gods, p. 107. ↩

- Sheftall, Blossoms in the Wind, see footnote on p. 61. ↩

- Astor, Operation Iceberg, p. 172. ↩

- Yuki Tanaka, Hidden Horrors: Japanese War Crimes in World War II (Boulder: Westview Press, 1996), pp. 207-209. ↩

- Inazō Nitobe, Bushido: Soul of Japan (Rutland: Tuttle, 1969), pp. 26-27. ↩

- Inazō Nitobe, Bushido, for Shinto see pp. 12, 14 and for Confucian see p. 15. ↩

- Inazō Nitobe, Bushido, pp. 80-81. ↩

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikaze Diaries, p. 1. ↩

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikaze Diaries, pp. 173-174. ↩

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikaze Diaries, pp. 11, and 175. ↩

- Sheftall, Blossoms in the Wind, p. 104. ↩

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikaze Diaries, pp. 10, 4-5 and 7. ↩

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikaze Diaries, p. 10. ↩

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikaze Diaries, pp. 55, 8, and 7. ↩

- USS Curtiss, Report of Pearl Harbor Attack, submitted 16 December 1941 (https://www.history.navy.mil/research/archives/digitized-collections/action-reports/wwii-pearl-harbor-attack/ships-a-c/uss-curtiss-av-4-action-report.html accessed 21 August 2020. Casualties included 20 dead (2 unidentified), 33 wounded and evacuated from ship, and 1 missing. ↩

- Richard B. Frank, Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire (New York: Penguin Books, 1995), p. 178. ↩

- Naitō, Thunder Gods, p. 107. ↩

- Ron Marans, Kamikaze in Color, DVD, (Thousand Oaks: Goldhil Video, 2002). ↩

- ‘There were multiple instances of U.S. crews giving the kamikaze pilots’ remains full military funeral honors burial at sea, including with an Imperial Japanese Rising Sun flag draping the body.’ Marans, Kamikaze in Color. ↩

- Frank, Downfall, p. 180 and Thomas J. Cutler, The Battle of Leyte Gulf (New York: Pocket Books, 1994), pp. 305-309. ↩

- Quoted in Cutler, The Battle of Leyte Gulf, p. 306. ↩

- Frank, Downfall, p. 180. ↩

- Frank, Downfall, p. 180, and Marans, Kamikaze in Color. ↩

- Keegan, The Second World War, p. 566. ↩

- Keegan, The Second World War, p. 572. ↩

- Sheftall, Blossoms in the Wind, p. 278. ↩

- Keegan, The Second World War, p. 573. ↩

- Sheftall, Blossoms in the Wind, p. 278. ↩

- Sheftall, Blossoms in the Wind, p. 192. ↩

- Naitō, Thunder Gods, p. 182 and Frank, Downfall, p. 159. ↩

- Frank, Downfall, p. 182. ↩

- Frank, Downfall, p. 182. ↩

- Frank, Downfall, p. 182, and Astor, Operation Iceberg, pp. 204-205. ↩

- Frank, Downfall, pp. 181-182. ↩

- USSBS (Pacific War), p. 10 and Astor, Operation Iceberg, p. 206. ↩

- USSBS (Pacific War), p. 10. ↩

- Sheftall, Blossoms in the Wind, pp. 433, and 436, and Samuel J. Cox, H-039-4: The First Kaiten Suicide Torpedo Attack, 20 November 1944, dated 26 December 2019, (https://www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-039/h-039-4.html accessed 21 August 2020). ↩

- USSBS, (Pacific War), p. 9 and Frank, Downfall, p. 206. ↩

- Frank, Downfall, p. 207. ↩

- Richard B. Frank, “Why Turman Dropped the Bomb”, The Weekly Standard, 8 August 2005, (https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/why-truman-dropped-the-bomb, accessed 24 August 2020). ↩

- Frank, “Why Truman Dropped the Bomb”. ↩

- Sheftall, Blossoms in the Wind, p. 373. ↩

- Toland, The Rising Sun, Volume 2, pp. 1057-1059. ↩

- Marans, Kamikaze in Color. ↩

- Sheftall, Blossoms in the Wind, p. 110. ↩

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikaze Diaries, p. 9. ↩

One Response to Kamikazes: Understanding the Men behind the Myths