Heather M. Haley

Auburn University

Over the 245-year history of the United States Navy, five ships were assigned the name Alabama with a sixth, a sloop-of-war, serving in the Confederate Navy. Congress authorized the production of the battleship Alabama (BB-60) in March 1934. The economic crash associated with the Great Depression, however, did not allow construction to begin until February 1, 1940, when dockworkers laid the keel in the Norfolk Navy Yard in a ceremony “as impressive as those that usually attend a launching.” 1 Even at this earliest stage in the production process—the placement of the structural keel in the dry dock cradle from which the ship ultimately grew—the vessel began to penetrate the public consciousness as an “imagined community.” While the idiom did not exist until political scientist Benedict Anderson defined it for the first time in 1983 to explain the global phenomenon of nationalism, Alabama nevertheless functioned as an imagined community, with its sailors allying themselves with the ship and engaging in lifelong fraternal fellowship with their comrades. Anderson labeled nations as both imagined because of the unlikelihood that members of even the smallest nations would know, meet, or hear of their fellows, and communities because the nation actively maintains “a deep, horizontal comradeship.” It is this “fraternity that makes it possible . . . for so many millions of people, not so much to kill, as willingly die for such limited imaginings.” 2

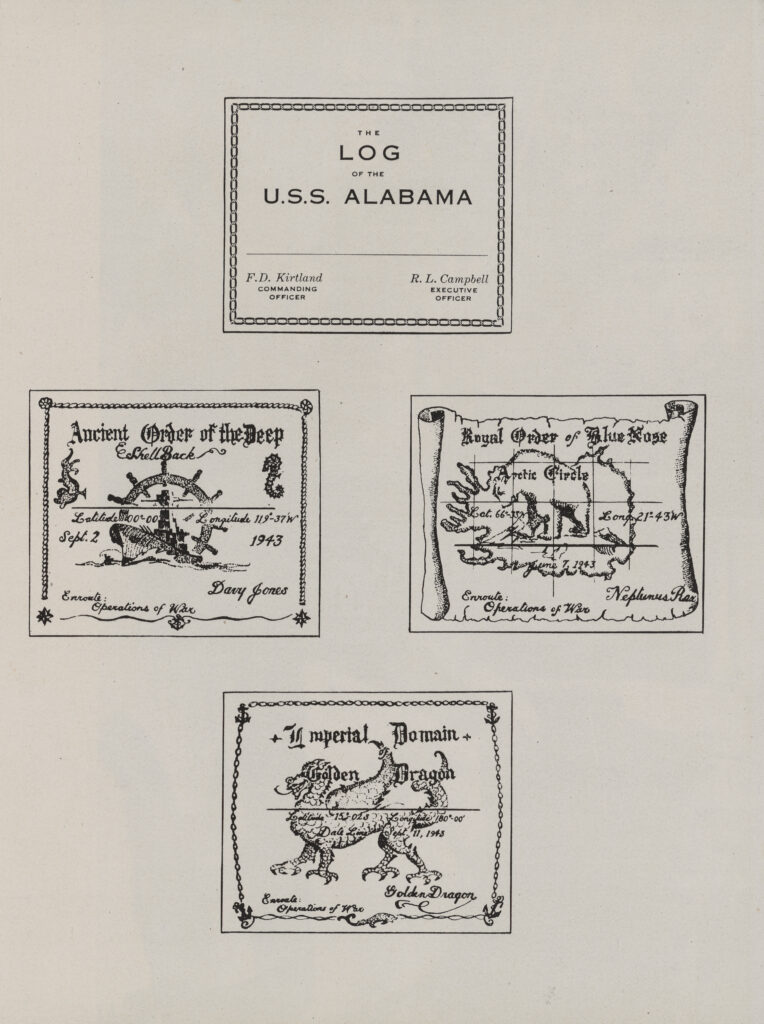

According to Anderson, three sequential causes are necessary for the rise of nationalist fervor. Print capitalism’s technological advancements in journalism and fiction, specifically those of penny presses, market media, and national distribution networks, made it possible for populations to “imagine” their linked and previously disjointed communities into one homogenous entity. Secondly, elite nationalists used language and status to build such communities where none had previously existed. Finally, nations severed ties with their imperial holdings around the globe. 3 While the U.S. military may never completely dissolve its complex worldwide network of military installations, which could arguably be described as a global military empire, the Department of the Navy took an active role to inculcate an esprit de corps among the crew assigned to Alabama, as it did with the crews of all its ships and installations. With this action, the vessel became a floating, mobile, imagined community as its crew exploited print capitalism’s technology in journalism through the at-sea publication of the daily workings of the vessel in its War Diary (1942-1944) and the post-war manuscript, Battleship USS Alabama, BB-60, published in 1993 following the establishment of the USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park in Mobile, Alabama. In addition, officers upheld traditional naval customs and ceremonies through their observance of the pranks and initiations traditionally associated with crossing the equator, entering the Arctic Circle, and passing over the International Date Line. These customs concluded with the ceremonial, albeit comical, distribution of “Ancient Order of the Deep,” “Royal Order of the Blue Nose,” and “Imperial Domain of the Golden Dragon” certificates for new initiates.

Ancient Order of the Deep (Shellback) certificate, ca. 1943-1945; Royal Order of the Blue Nose (Arctic Circle) certificate, a. 1943-1945; Imperial Domain of the Golden Dragon (International Date Line) certificate, ca. 1943-1945. (Images courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History)

Veteran testimonies enrich such naval histories to give voice to this often-excluded group. The interviews themselves emphasize empowerment among enlisted veterans as they recover and interpret their pasts rather than having them interpreted or imposed upon them by others. 4 Benedict Anderson, a scholar of international studies, acknowledged a similar anomaly when he opined, “All profound changes in consciousness, by their very nature, bring with them characteristic amnesias.” 5 These amnesias and imposed interpretations of the past are further explored by American cultural historian Alison Landsberg with her analysis of “prosthetic memories,” or ‘memories forged in response to modernity’s ruptures,” most notably those of mass culture. The veteran oral histories found here, mostly from enlisted sailors with a smattering of commentary from commissioned officers, express the ways in which sailors endowed Alabama—initially an “undifferentiated space”—with experiential value, thereby transforming it into a place, or an imagined community. 6

Not only is this a history of specific events, but more importantly, it is about what these events mean to those who experienced them. These recorded memories, therefore, are interpreted life events rather than a linear chronicling of the past. The resulting narrative from oral history interviews is not necessarily fluid or articulated in a precise chronological fashion. Thus, the analysis is often causational as an interviewee’s social and cultural processes shape their subjectivity and recollections. By adopting the theoretical frameworks of Anderson, historians Eric Hobsbawm, Alison Landsberg, and humanistic geographer Yi-Fu Tuan, the analysis that follows provides a sociological lens through which historians might analyze a ship’s transformation from a work and living space into an imagined community to which sailors dedicate themselves. Veteran testimonies offer concrete examples of the ways in which they, and their contemporaries, engaged in socializing hijinks, “conventions of behavior,” and “invented traditions” that not only ensured “group cohesion,” but initiated a camaraderie and allegiance that transcended decades. 7

In 2000, Congress authorized the creation of the Veteran’s History Project to collect and preserve American war veterans’ testimonies. 8 9 Included within this ongoing series is a small, digitized collection of eight oral accounts from Alabama sailors—the only interviews available for reference at the time of this publication. While the questions posited to interviewees are standardized, with only rare instances of script deviation, veterans not only recalled the moments of overwhelming terror in battle in the Pacific but even the most mundane daily routines. Memory and its associated process of remembering are essential to oral history, as the interviewee’s recollections serve as the evidentiary source. As a process of remembering, memory involves the “calling up of images, stories, experiences, and emotions from our past life, ordering them, placing them within a narrative story and then telling them in a way that is shaped at least in part by our social and cultural context.” 10 As a result, memory is an active process in which an individual’s trace memories maintain a symbiotic relationship with the public memorialization of the past. Thus, memory is a socially shared experience.

Scholarship on naval vessels rarely engages with oral history as the central methodological practice. This practice is not unusual, as incorporating personal testimonies into the historical narrative places the additional burden on historians to determine “verifiability, reliability, validity, and representation as defined by the dominant intellectual structures” of the discipline. 11 Therefore, oral historians must be conscious of and actively identify prosthetic memories. Alison Landsberg, associate professor of history at George Mason University, identified this phenomenon in Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture when she argued that the advanced technologies of mass culture—the internet, interactive museum exhibits, movies, and television dramas—and “the capitalist economy of which they are a part open up a world of images outside a person’s lived experience, creating a portable, fluid, nonessentialist form of memory.” Like a prosthetic limb, these memories are not organic products of lived experience, but are nevertheless useful because, to the oral history interviewee, “they help condition how the person thinks about the world” and their relation to global events. 12

When involving oneself in memory studies, it is prudent for the researcher to be aware of the interviewee’s power to distort or shape recalled memories. Memory is fallible. While external mass cultural processes may have entered veterans’ consciousness and could thereby alter individual and sometimes traumatic wartime experiences, the inclusion of personal memories nevertheless transforms an otherwise elitist and official narrative into one of diverse inclusion. People retain memories over long periods, often with no significant memory loss because people are more likely to remember important experiences, images, stories, and emotions. 13 While some intricate details might fade, broad concepts remain throughout life.

USS Alabama as an Imagined Community

Ancient Greek and Roman seafarers sought the good graces and favor of the seas’ monarch: Poseidon and Neptune in Greek and Roman mythology, respectively. Ancient Greek ship-launching spectators wreathed themselves with olive branches, drank copious amounts of wine to honor the gods, and blessed the new vessel with water. 14 The ceremony currently executed by the U.S. Navy consists of the official recitation of the vessel name by a female sponsor, followed by a speech, and the breaking of a bottle of wine or champagne on the bow of the ship as she slips down the ways. Tradition maintained the use of water in the baptismal ceremonies of seafaring vessels in the western world until the first attempt to christen and launch the USS Constitution in September 1797, but “Old Ironsides” would not move without “a bottle of choice old Madeira.” 15

With the explicit intention of strengthening the American fleet across the globe, Alabama was the fourth ship of the South Dakota-class battleships. At the time of Alabama‘s commissioning in August 1942, there had been three Navy ships previously named after the Yellowhammer State and a screw sloop-of-war that saw vigorous combat as a Confederate-flagged commerce raider during the American Civil War. The Norfolk Navy Yard construction crew laid the keel in February 1940, and at completion, the ship was 680 feet in length and could displace 44,500 tons of water when fully loaded with a crew of 2,200 enlisted men and 127 officers. Deep in the vessel’s underbelly, a hydroelectric power plant enabled the massive ship to plow through waves at a top speed of almost 28 knots, approximately 32 miles per hour. 16

Whispered rumors of the technological enhancements of the South Dakota-class battleship’s electrical and combat systems undoubtedly spread among enlisted sailors who clamored to attend the ship’s christening by sponsor Henrietta Hill, wife of Alabama senator Lister Hill. Days before the launching, in a Western Union telegram to Alabama Governor Frank M. Dixon, Rear Admiral, Felix Gygax, Commandant of the Norfolk Navy Yard, advised the governor of newspaper reports predicting a “very large group from Alabama planning to attend launching.” 17 In a handwritten letter addressed to Alabama governor Frank Dixon, dated February 9, 1942, the father of midshipman James C. Sullivan, Jr. requested an invitation to Alabama’s launching on behalf of his son. The letter confirms that the midshipman, who was then completing his final year at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, was not assigned to the battleship, but his residency in the state of Alabama compelled his attendance at such an “auspicious occasion.” 18

This correspondence suggests the ship’s role as an imagined community, as the father and son duo maintained their ties to “nationality as a socio-cultural concept.” 19 Although assigned to another vessel or duty station, the midshipman publicized his admiration for, and allegiance to, his native Alabama through this correspondence to Governor Dixon. Midshipman Sullivan’s residency and culturally rooted association with Alabama necessitated his attendance at the christening ceremony. It also speaks to the work of humanistic geographer Yi-Fu Tuan, who proposed the idea that an object, like the USS Alabama, “becomes a symbol when its own nature is so clear and so profoundly exposed that while being fully itself it gives knowledge of something greater.” 20 Additionally, Dixon subtly perpetuated Alabama’s association as an imagined community by using his elite and political status as governor to inquire on behalf of Sullivan if it would be at all possible for him to attend the christening.

The Western Union telegram from Rear Admiral Gygax that predicted crowds of attendees from Alabama further informed Governor Dixon that admittance into the Norfolk Navy Yard for the christening ceremony was possible but restricted to attendees with a pass. 17 This official correspondence confirms Dixon’s willingness to inquire about attendance on behalf of his constituents, thus reinforcing notions of patriotism, allegiance, and political patronage that created or tightened his existing sponsorships. This pair of primary sources preserved within the Alabama Department of Archives and History emblemizes Benedict Anderson’s concept of nationalism and allegiance concerning this imagined community. Here, two imagined communities emerged to inspire loyalty—one the state, one the ship. While this overlap is powerful for some people, one community can undoubtedly exist independently of the other, especially for sailors who did not hail from Alabama. With its patriotic music, dress uniforms, and the historical commemoration of the technologically advanced warship named after the Heart of Dixie, the centuries-old christening ceremony only reinforced nationalistic emotions and the fervor directly associated with this imagined community.

Literacy

In the earliest days of the ship’s infancy, Alabama conducted a shakedown cruise, during which time the crew tested machinery, adjusted instruments accordingly, and familiarized themselves with the daily administration and operation of the ship. 22 On one uncharacteristically stress-free morning during this shakedown cruise, Lieutenant (junior grade) Ivan W. Parkins received the day’s orders and passed along its contents to each division as necessary. The document was lengthy and detailed, and Parkins commanded a subordinate, who he “knew by that time was a little more than the average in terms of leadership and responsibility,” to read the orders aloud. 23 The seaman respectfully declined. When ordered a second time, the crewman again declined. Parkins turned to his boatswain—the chief petty officer of the division—to determine why this crewman refused his order. To his surprise, Parkins learned that the deck crew had, on average, three or four years of elementary school education. Parkins acknowledged how the officers “had been quite neglectful about education” and, therefore, took it upon himself as the junior officer to improve literacy among his subordinates. He recalled:

One of the first things I got to do was to administer an exam, which somebody else had drawn up. . . . I didn’t think the exam was fair because it assumed far too much in reading capacity and writing capacity. Later I got to make up an exam for a similar purpose, and I tried to make it multiple choice and as few words and simple as I could. . . When I started asking around who would want to try for the next set of tests for an advancement, I got 40 percent of the people in the division. . . [but] I guess [they] lost the books from which they were studying to prepare. The division officers thought that was careless and wouldn’t get more books. . . I convinced the new division officer, my immediate superior, that we needed to get books for ’em. We got everyone supplied with books. We set up schedules so that the senior petty officers could teach the people from the rank below what they would need to know for an advance in rating. 24

Ultimately, every crewmember who participated in Parkins’ educational reform program passed their advancement exams. The success of Parkins’ top-down educational program, with other officers’ support, reinforced the communal nature of literacy in Alabama’s homogenization as an imagined community.

Ceremony

By August 1943, the Department of the Navy assigned Alabama to the Pacific Fleet, where she joined fast carrier task forces in providing fire support and anti-aircraft screening during numerous invasions, landings, raids, and pitched battles. The following month, the battleship Alabama departed Norfolk, Virginia, and sailed through the Panama Canal to join the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet. Apprehensive pollywogs, or “wogs,” those sailors who had not yet crossed the equator, and their seasoned “shellback” shipmates participated in a time-honored tradition colloquially known as “crossing the line.” These ceremonies often occur upon the occasion of crossing the equator, although sailors have created variations of the ceremony for passing through the tropics, the International Date Line, and the Arctic Circle. 25

These ceremonies were grueling and often conducted over multiple days to test inexperienced crewmembers for life at sea. This event grew out of antiquity as the mythical Roman god of the seas, Neptune, would only be satiated and appeased through the crew’s respect. 26 The traditional dramatic production, often involving costumes, props, and script-reading, emphasized the U.S. Navy’s instillation of an esprit de corps as these rehearsed events imitated ancient judicial and initiation ceremonies. The three particularly scripted and momentous junctures in the production—when Davy Jones summons the captain, who transfers his power to Neptune, and the subsequent trial and punishment of all pollywogs—exemplify the subsequent exercise in social control through the issuance of discipline to crewmembers by crewmembers, potentially of equitable rank. 27

The dramatic oration of scripts and readings from mock proclamations or rehearsed routines order the events and give them a symbolic inversion of dignified military judicial ceremonies. The scripted narratives highlight the exercise of social control and discipline. Amid general scenes of fraternal mayhem, as pollywogs shuffled through various torments imposed upon them by shellbacks, the scripts helped to maintain the traditional mythological belief underscoring the narrative structure. When Davy Jones came aboard for the first time as the arbiter of festivities, for instance, he ceremoniously addressed the captain, affirming that “there will be no leniency—all pollywogs will receive appropriate punishment.” 28 In the script, Jones foreshadows the next day’s rough treatment and warns pollywogs to take these festivities seriously. Here the crew accepted, unknowingly and perhaps begrudgingly, Benedict Anderson’s concept of inheritance. Crewmembers of Alabama not only perpetuated tradition but reinforced the establishment of the ship as an imagined community through their participation in this “historically deep-rooted” ceremony. 29

The modern navy’s line-crossing ceremonies remain as colorful as those engaged in centuries ago. The oldest and most dignified senior shellback of the crew assumes the role of Neptunus Rex and selects his assistant, Davy Jones. Her Highness Amphitrite “is usually a good looking young seaman who will appear well in a deshabillé of seaweed and rope yarns.” 30 The Court usually consists of the Royal Scribe, the Royal Doctor, the Royal Dentist, the Devil, and other names invented by the Neptune party. The Bears have the difficult task of rounding up pollywogs and distributing their official “summons”:

IN THE ROYAL COURT OF THE REALM OF NEPTUNE

In And For The District Of EquatoriusSUBPOENA

INHABITANTS OF THE REALM OF THE DEEP

VS

Pollywog _________________________________ U.S. Navy.

You are hereby commanded to appear before the ROYAL COURT OF THE REALM OF NEPTUNE, in the DISTRICT OF EQUATORIUS, because it has been brought to the attention of HIS AUGUST HIGHNESS NEPTUNE REX through his trusty SHELLBACKS, that the good ship REGULUS is about to enter those waters manned by a crew who has not acknowledged the sovereignty of the RULER OF THE DEEP, has transgressed on his domain and thereby incurred his Royal displeasure.

THEREFORE be it known to all ye Box Car Tourists, Park Statues, Cream Puffs, Hay Makers, and Politicians that His Most Royal Muchness NEPTUNE REX, Supreme Ruler of all Mermaids, Sharks, Squids, Crabs, Pollywogs, Eels and other denizens of the deep, will, with his Secretary and Royal Court, meet in full session on board the offending ship REGULUS on __ day of October, A.D. 1943 to hear your defense on the charge of:

It is therefore ordered and decreed that the above named man present himself before the above Court at the time and place above mentioned or else be condemned to become food for Sharks, Whales, Pollywogs, Frogs, and all other scum of the sea, who will devour you – head, body and soul – as a warning to any Landlubbers entering my Domain, disobey this order under my displeasure – INCARNATION IN DAVY JONES’ LOCKER!!!

BY ORDER OF THE COURT:

Given under my hand this __ Day of October, 1943.[signed] DAVY JONES, Clerk,

Honorable Pegleg,

Deputy. 31

According to a 1957 publication documenting French, British, American, Dutch, German, and Russian ceremonies, “no custom of the sea is better known, for to qualify as a ‘shellback’ is a distinction desired by all sailormen.” 32 Douglas Manger, a former American sailor who participated in the ceremony in the 1960s, aligned the ritual with depictions of masculinity, as a means to prove ability and manhood. While Manger had a strong sense of his participation in a grand tradition that encouraged and reinforced “those masculine traits that have always defined ‘true’ Navy men,” including “queer branding and homophobic paranoia,” this unofficial simulation for social cohesion was abusive. Pollywogs had to “endure the humiliation of the ritual” to prove that they were salty dogs, real men. 33 It is here that historian Eric Hobsbawm’s idea of “invented tradition” comes to the fore. He defined this concept as “a set of practices . . . of a ritual or symbolic nature, which seek to inculcate certain values and norms of behavior by repetition, which automatically implies continuity with the past.” 34 He argued that the invention of tradition is universal, but occurs most frequently in periods of rapid social change. In the instance of the crossing the line ceremony, the function of the invented tradition was to legitimize relations of authority and establish or symbolize social cohesion within this imagined community. 35

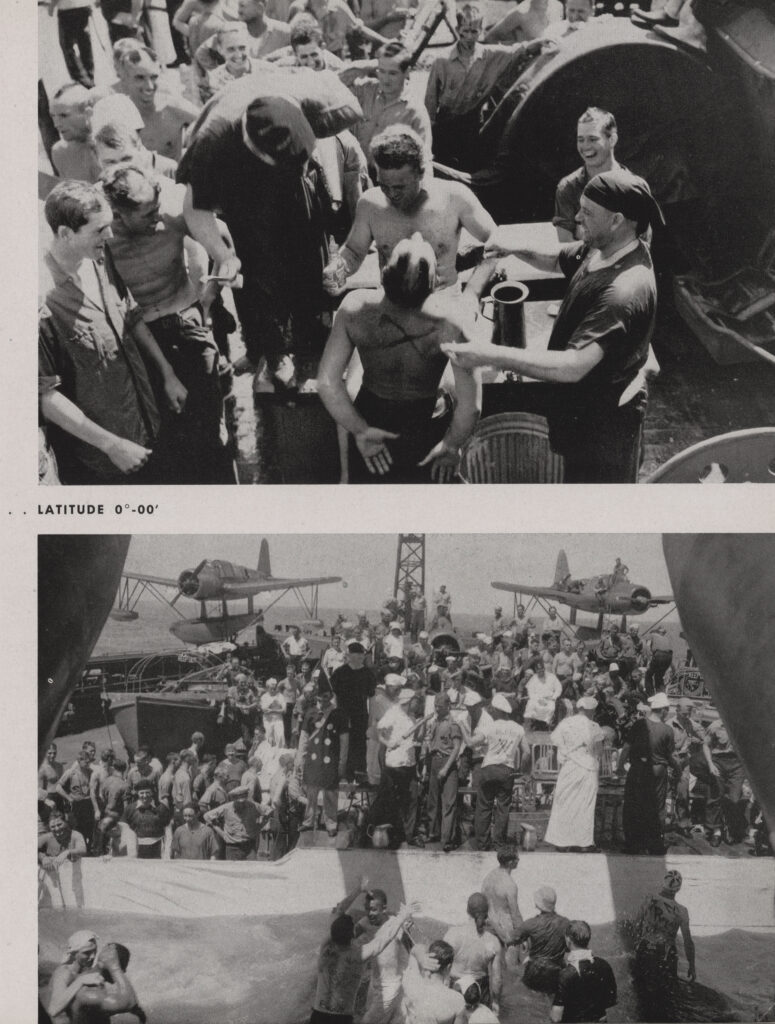

U.S.S. Alabama crew participates in crossing the Line ceremony, ca. 1943-1945. (Images courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History)

When Neptune stepped aboard Alabama with his royal entourage on September 2, 1943, the captain had the opportunity to beseech the king of the seas to be merciful, especially to his pollywog officers, but Neptune insisted that there would be no exceptions. In his most gracious tone and manner, the captain told Neptune, “It is a great pleasure to have you aboard,” to which Neptune replied, “The displeasure is all mine.” Neptune then complained that Alabama was “sorely infested with nefarious and slimy pollywogs, a situation which my Royal Party intends to correct by making them fit Shellbacks.” The captain then yielded his authority with the words, “I turn over my command to you for such time as you wish.” 36 Pollywogs were entirely unaware of the trials they were to undergo over the course of the ceremony. This tradition reinforces Yi-Fu Tuan’s idea that experience requires the individual to confront the unfamiliar and uncertain in order to learn in the most active sense. 37 LTJG Parkins recalled his participation in the festivities:

I made a mistake . . . that I’d go first and get it over with. The thing was that on that ship there were few people who had been across [the equator] . . . and with hundreds of Marines aboard, they got very tired before they got through [everyone]. For those of us who went first, I had my hair clipped with tin snips. I had Vaseline and lamp black rubbed into me. I was fed some kind of hot mixture, beaten with wet towels, [and] I don’t know what else. 23

The perpetuation of this frequently humiliating tradition was a means to create a unifying sense of identity through which the crew could solidify their membership within this imagined community. The invented tradition of the crossing the line ceremony aboard Alabama was a formalization process characterized by reference—and reverence—to the past through repetition in the present. 39

The editors of the ship’s War Diary were sure to commemorate these ceremonies in their publication noting:

Veteran officers and men of the ALABAMA are more than qualified members of the Ancient and Honorable Orders of BLUENOSES, SHELLBACKS, and THE GOLDEN DRAGON, for she has crossed the ARCTIC CIRCLE 6 times, the 180th MERIDIAN an equal number of times, and the equator no less than 24 times. 40

While this statement indicates that all Alabama veterans are entitled to the rights and privileges as sailors who crossed the Arctic Circle, the Equator, and the International Date Line, respectively, it is unclear to what extent sailors of color participated in any of these activities. There remains a paucity of source material on the ship’s African American crew. Images of the Alabama’s basketball, baseball, and boxing teams included in the War Diary depict all-white athletes with no mention of any segregated equivalents. With the exception of W Division’s group photo and a crude drawing of an African American boxer, the ship’s War Diary chronicles the activities of its predominantly white crew. The absence of African American crewmen in images of crossing the line ceremony festivities implies that the segregation that characterized the World War II Navy transcended traditions considered sacrosanct to white sailors. The exclusion of Alabama’s African American sailors from the “deep, horizontal comradeship” of unofficial ceremonies, their absence in commemorative historical documents, and their experiences neglected from oral history projects affirm Benedict Anderson’s conclusion that while the “imaginings of fraternity” seemed to emerge “naturally,” the group was not homogenous, rather, fractured by racial antagonisms. 41

Post-War Service in the United States Pacific Reserve

In October 1945, Alabama steamed into San Francisco Bay, where Captain E. J. Pierce relieved Captain William Goggins as commanding officer. Japan had surrendered in September, and the war was over. The “relaxation of censorship restrictions” in that year allowed Personnelman Jack Burgeman “to tell all—or at least almost all” to his brother Clarence. In a piece of intimate correspondence, Jack lamented:

This rather sounds like an obituary. In a way it is, for in every nook and corner, the men are sitting around in groups dreaming of home. . . . And everywhere there is the sad realization that the best crew that ever served together is about to break up. It is the end of a grand association together and makes you feel sad in the same sort of way you felt when it came time to leave school and all the old comrades you knew and with whom you had shared countless experiences, both good and bad. When one of these groups grows silent, it is this nostalgic feeling that always makes someone say, “Do you remember–––?” 42

Burgeman’s lamentations confirm that sailors assigned to Alabama associated the vessel with place, not space. Etymological clarification between the two terms is necessary. According to Tuan, place is a unit measured by location—imbued with history and meaning as it somehow absorbs the “experiences and aspirations” from the consciousness of the individual that may be revived at a later time, whereas space is vast and quantifiable through the language of mathematics. 43 Having begun as an undifferentiated object, Alabama became a place as the crew endowed it with experiential value.

In addition to her receipt of the Navy Occupation Service Medal and the Philippine Republic Presidential Unit Citation Badge, the U.S. Navy awarded Alabama nine battle stars on the Asiatic-Pacific Area Service Medal for her service against hostile forces in the Pacific. Two years later, she sailed to Seattle, where she was decommissioned as a ship of the line and placed in reserve. 44 Initially intended for scrap, whose salvage would repurpose newer vessels of the fleet, Alabama received public attention from Congressional delegations and countless Alabamians to save the vessel. Assistant Tailor Glen C. Lindstrom remembered:

Governor [George] Wallace was very much on the ball. He wanted to save USS Alabama and bring it up into his coastline, and he thought of some very good ideas. He put all of the kids in the state of Alabama to work to take collections every Wednesday, in what they called “penny Wednesday” and preserve those funds. They picked up close to $1 million for bringing USS Alabama down the west coast, through the Panama Canal, and up into Mobile Bay so to conserve it. 45

In September 1963, with the support of Governor George C. Wallace, the Alabama Legislature created the USS Alabama Commission, instilled with the responsibility to raise funds to have the ship towed an unprecedented 5,600 miles from Bremerton, Washington, through the Panama Canal, to Mobile Bay in order to establish a memorial park in memory of all Alabamians who served in World War II and Korea. Ultimately, this Act expanded to include Alabamian veterans of all wars. The residents of Alabama, the majority of whom were schoolchildren, managed to raise $100,000 from “penny Wednesday” collections. Additional fundraising efforts by life insurance agencies and local financial institutions in Mobile raised an additional $700,000. These funds were exclusively allocated to preserve the ship by providing low-interest loans to keep the memorial park in operation. In the early summer of 1964, the U.S. Navy transferred the ship’s title to the state of Alabama, and on September 12, 1964, she arrived in Mobile, where she dropped anchor for the last time. 46

The memorial park itself and the subsequent establishment of the USS Alabama Crewman’s Association allowed for the private publication of Battleship USS Alabama, BB-60. This monograph, coupled with the at-sea publication of the vessel’s pictorial War Diary, utilized print capitalism to promote the idea that the vessel was, and remains, an imagined community to this group of veterans. In August 1965, 30 veterans of the ship founded the Crewman’s Association, and at the time of the publication commemorating the establishment of the memorial park, membership in the organization swelled to 1,100 former members of the crew and their families. Here, they “try to embody their feelings, images, and thoughts” in this tangible, architectural space. 47 Thus, former crew members and their families acknowledged Alabama with its associated publications and veterans’ organizations as a center of value for those who lived and worked in this imagined community.

Nothing appears more linked to an ancestral past than the pageantry surrounding U.S. Navy servicemen and women with their participation in various ceremonies and initiations. Even in its modern form, it is the product of ancient and invented tradition. Anyone intimately familiar with the U.S. Navy will recall such traditions at a personal level through intimate recollections of the christening of navy vessels, crossing the line, entering the Arctic Circle, and the formation of a memorial park or a museum exhibit. The term “invented tradition” includes traditions actually invented, constructed, and formally instituted. Historian Eric Hobsbawm identified invented tradition “to mean a set of practices, normally governed by overtly or tacitly accepted rules and of a ritual or symbolic nature, which seek to inculcate certain values and norms of behavior by repetition, which automatically implies continuity with the past.” 48 In so doing, these traditions establish continuity with a historic past. Invented traditions—including vessel christenings and crossing the line ceremonies—belong to three often-overlapping functions, as they exist to establish social cohesion within the imagined community, legitimize the authority maintained by senior officers, and instill beliefs, value systems, and conventions of behavior within the larger organization. While social cohesion is most easily seen, the other functions flowed from a sense of identification with the vessel as an imagined community. 49

Similarly, Benedict Anderson’s concept of nationalism—the sense of identification or belonging expressed toward the nation and other members of the imagined community—can be applied to Alabama. The invented traditions perpetuated by the U.S. Navy, including christening, informal initiation ceremonies, and the establishment of memorial parks, are incredibly emotive cultural forms through which service members express their allegiance to the imagined community. In order to explain the global phenomenon of nationalism, Anderson labeled nations as both imagined because of the unlikelihood that citizens would know, meet, or hear of their fellows and communities because the nation actively maintains “a deep, horizontal comradeship” and it is this “fraternity that makes it possible . . . for so many millions of people, not so much to kill, as willingly die for such limited imaginings.” 50 The sailors aboard Alabama may not have known, let alone met, every one of their 2,326 shipmates, but their collectively shared experiences solidified the vessel’s place as an imagined community. Seaman Second Class Ford Curtiss Thompson recalled how he managed to make it down to the Alabama moored in Mobile Bay “two or three times.” The U.S.S. Alabama Crewman’s Association has “a reunion every year,” he continued. “I don’t go every year, but I’d like to.” At the first reunion Thompson attended, he claimed only to know “two or three guys that was on the ship when [he] was there.” 51

In preparation for the fiftieth anniversary convention in Mobile, Chief Botswain’s Mate John P. Ryan, with the help of his family, made a concerted effort to update his uniform so that he might appropriately honor his service to the ship. “I take a lot of pride having served,” Ryan beamed. Ryan reminisced about the “old jitterbug days,” after his transfer to the Alabama in September 1942, “when sailors would dance with each other” as the ship’s band performed at sunset. Ryan confirmed that the crew aboard Alabama included a celebrity, baseball player Bob Feller, “who received a lot of recognition.” 52 In 2006, Congress read his professional baseball and naval performances into the Congressional record.

At the peak of his baseball career, Robert William Andrew Feller was sworn in to service two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor and served aboard Alabama as a gunner’s mate “where he kept his pitching arm in shape by tossing a ball on the deck.” He earned eight battle stars and was discharged in late-1945. 53 While Feller’s oral history with the Library of Congress is succinct, amounting to only 11 minutes of commentary, Feller told interviewer Donald Adams, “I certainly had a great experience in the Navy . . . I am very proud of my Navy experiences.” 54 Ford Thompson admitted that he “didn’t have a lot of friends” aboard Alabama since his position as yeoman to the chaplain sequestered him to the library, but he managed to strike up a friendship with Feller. “Him and I became good friends because we was both from Iowa, and I would trade [news]papers with him,” Thompson explained. 51 Although Feller was a professional baseball player of some renown, whose reputation heightened following the publicization of his enlistment, the shared collective experience aboard Alabama that came with his enlistment was an equalizer that elicited camaraderie and lifelong friendship with his shipmates.

The scholarship of geographer Yi-Fu Tuan primarily centers on the way human beings interact with and experience their surrounding environments. As such, Tuan focuses on the concept of experience, calling it “a cover-all term for the various modes through which a person knows and constructs a reality.” 56 When asked to participate in the design of the tailor shop exhibit aboard Alabama, former Assistant Tailor Glen C. Lindstrom jumped at the opportunity:

When I left the ship to go home, which was back in the Minneapolis area, I picked up a few items from the tailor shop and mailed it home because I thought someday I will want to go back and restore the tailor shop. I did in 1988. I had enough equipment and stuff to go back to restore it. . . . There is only one thing missing and that’s a lampshade. 45

By moving through and responding to USS Alabama (BB-60) as a place—not a space—Lindstrom and those of his shipmates who participated in the establishment of the ship as a memorial park, or in crossing the line hijinks as enlisted sailors decades before, arranged their worldviews into similar structured and meaningful “centers of felt value.” 58

(Return to December 2020 Table of Contents)

Footnotes

- U.S.S. Alabama History, n.d., Barbara Dickinson USS Alabama Collection, PR333, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama. ↩

- Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, rev. ed. (London: Verso, 2006), 7. ↩

- Ibid., 109-111. ↩

- Mary A. Larson, “Research Design and Strategies,” in History of Oral History: Foundations and Methodology, ed. Thomas L. Charlton, Lois E. Myers, and Rebecca Sharpless (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007), 106, 107. ↩

- Anderson, Imagined Communities, 204. ↩

- Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977), 6. ↩

- E. J. Hobsbawm, “Inventing Traditions,” introduction to The Invention of Tradition, ed. E. J. Hobsbawm and T. O. Ranger (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 9, 13. ↩

- Alison Landsberg, Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 2. ↩

- Veterans’ Oral History Project Act, Pub. L. No. 106-380, 114 Stat. (October 27, 2000). ↩

- Lynn Abrams, Oral History Theory (London: Routledge, 2010), 78-79. ↩

- Ronald J. Grele, “Oral History as Evidence,” in History of Oral History: Foundations and Methodology, ed. Thomas L. Charlton, Lois E. Myers, and Rebecca Sharpless (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007), 56. ↩

- Landsberg, Prosthetic Memory, 18, 24. ↩

- Ibid., 85, 86. ↩

- John C. Reilly, “Christening, Launching, and Commissioning of U.S. Navy Ships,” Naval History and Heritage Command, last modified June 23, 2014, accessed October 8, 2016, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/

history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/christening-launching-and-commissioning-of-u-s-navy-ships.html ↩

- William P. Mack, Royal W. Connell, and Leland P. Lovette, Naval Ceremonies, Customs, and Traditions, 5th ed. (Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1980), 172-173. ↩

- Battleship USS Alabama, BB-60, 14. ↩

- Telegram from Felix Gygax to Frank M. Dixon, Alabama Governor (1939-1943: Dixon), SG12234, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama. ↩

- J. C. Sullivan to Frank Dixon, February 9, 1942, Frank Dixon Papers, SG12234, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama. ↩

- Anderson, Imagined Communities, 5. ↩

- Tuan, Space and Place, 114. ↩

- Telegram from Felix Gygax to Frank M. Dixon, Alabama Governor (1939-1943: Dixon), SG12234, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama. ↩

- Mack, Connell, and Lovette, Naval Ceremonies, Customs, and Traditions, 279. ↩

- Ivan W. Parkins Collection (AFC/2001/001/55401), Video recording (MV01), Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Simon J. Bronner, Crossing the Line: Violence, Play, and Drama in Naval Equator Traditions (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2006), 8. ↩

- Mack, Connell, and Lovette, Naval Ceremonies, Customs, and Traditions, 186. ↩

- Bronner, Crossing the Line, 17. ↩

- Full text reprinted in Bronner, Crossing the Line, 17-19 ↩

- Anderson, Imagined Communities, 196. ↩

- Harry Miller Lydenberg, comp., Crossing the Line: Tales of the Ceremony during Four Centuries (New York: New York Public Library, 1957), 152. ↩

- “Crossing the Line: Historic Documents,” Naval History and Heritage Command, last modified May 12, 2014, accessed November 25, 2016, https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/heritage/customs-and-traditions/crossing-the-line/historic-documents.html; “Crossing the Line: Pollywogs to Shellbacks,” Naval History and Heritage Command, last modified July 9, 2017, accessed September 3, 2020, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/customs-and-traditions0/crossing-line.html. ↩

- Lydenberg, Crossing the Line, 192. ↩

- Personal correspondence with Douglas Manger reprinted in Bronner, Crossing the Line, 45. ↩

- Hobsbawm, “Inventing Traditions,” introduction to The Invention of Tradition, 1. ↩

- Ibid., 4, 9. ↩

- Reprinted in Bronner, Crossing the Line, 19. ↩

- Tuan, Space and Place, 9. ↩

- Ivan W. Parkins Collection (AFC/2001/001/55401), Video recording (MV01), Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress. ↩

- Hobsbawm, “Inventing Traditions” in The Invention of Tradition, 1, 4. ↩

- War Diary, U.S.S. Alabama, 1942-1944, D774.A4 W37, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama. ↩

- Anderson, Imagined Communities, 7, 203. ↩

- Photocopy of letter from Jack Burgeman to Clarence Burgeman, 8/29/45, Jack Burgeman Collection, Box 1, Folder 2, Pritzker Military Museum and Library, Chicago, Illinois. ↩

- Yi-Fu Tuan, “Space and Place: Humanistic Perspective,” in Philosophy in Geography, ed. Stephen Gale and Gunnar Olsson (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 1979), 387. ↩

- Battleship USS Alabama, BB-60, 37. ↩

- Glen C. Lindstrom Collection (AFC/2001/001/51412), Audio recording (SR01), Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress. ↩

- Battleship USS Alabama, BB-60, 6, 40. ↩

- Tuan, Space and Place, 17. ↩

- Hobsbawm, “Inventing Traditions” in The Invention of Tradition, 1-2. ↩

- Ibid., 9. ↩

- Anderson, Imagined Communities, 7. ↩

- Ford Curtiss Thompson Collection (AFC/2001/001/102395), Transcript (MS04), Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress. ↩

- John P. Ryan Collection (AFC/2001/001/50545), Video recording (MV01), Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress. ↩

- Commemorating the 60th Anniversary of the Historic 1946 Season of Major League Baseball Hall of Fame Member Bob Feller and His Return from Military Service to the United States, H.R. Res. 449, 109th Cong., 2d Sess. (July 25, 2006). ↩

- Robert William Andrew Feller Collection (AFC/2001/001/55642), Audio recording (SR01), Veteran’s History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress. ↩

- Ford Curtiss Thompson Collection (AFC/2001/001/102395), Transcript (MS04), Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress. ↩

- Tuan, Space and Place, 8. ↩

- Glen C. Lindstrom Collection (AFC/2001/001/51412), Audio recording (SR01), Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress. ↩

- Tuan, Space and Place, 8, 4. ↩

One Response to Neptune’s Commandments: Invented Traditions and the Formation of USS Alabama (BB-60) as an Imagined Community